Under this plan, SpaceX’s satellites would play a big role in the Space Force’s kill chain.

The Trump administration plans to cancel a fleet of orbiting data relay satellites managed by the Space Development Agency and replace it with a secretive network that, so far, relies primarily on SpaceX’s Starlink Internet constellation, according to budget documents.

The move prompted questions from lawmakers during a Senate hearing on the Space Force’s budget last week. While details of the Pentagon’s plan remain secret, the White House proposal would commit $277 million in funding to kick off a new program called “pLEO SATCOM” or “MILNET.”

The funding line for a proliferated low-Earth orbit satellite communications network hasn’t appeared in a Pentagon budget before, but plans for MILNET already exist in a different form. Meanwhile, the budget proposal for fiscal year 2026 would eliminate funding for a new tranche of data relay satellites from the Space Development Agency. The pLEO SATCOM or MILNET program would replace them, providing crucial support for the Trump administration’s proposed Golden Dome missile defense shield.

“We have to look at what are the other avenues to deliver potentially a commercial proliferated low-Earth orbit constellation,” Gen. Chance Saltzman, chief of space operations, told senators last week. “So, we are simply looking at alternatives as we look to the future as to what’s the best way to scale this up to the larger requirements for data transport.”

What will these satellites do?

For six years, the Space Development Agency’s core mission has been to provide the military with a more resilient, more capable network of missile tracking and data relay platforms in low-Earth orbit. Those would augment the Pentagon’s legacy fleet of large, billion-dollar missile warning satellites that are parked more than 20,000 miles away in geostationary orbit.

These satellites detect the heat plumes from missile launches—and also large explosions and wildfires—to provide an early warning of an attack. The US Space Force’s early warning satellites were critical in allowing interceptors to take out Iranian ballistic missiles launched toward Israel last month.

Experts say there are good reasons for the SDA’s efforts. One motivation was the realization over the last decade or so that a handful of expensive spacecraft make attractive targets for an anti-satellite attack. It’s harder for a potential military adversary to go after a fleet of hundreds of smaller satellites. And if they do take out a few of these lower-cost satellites, it’s easier to replace them with little impact on US military operations.

Missile-tracking satellites in low-Earth orbit, flying at altitudes of just a few hundred miles, are also closer to the objects they are designed to track, meaning their infrared sensors can detect and locate dimmer heat signatures from smaller projectiles, such as hypersonic missiles.

The military’s Space Development Agency is in the process of buying, building, and launching a network of hundreds of missile-tracking and communications satellites. Credit: Northrop Grumman

But tracking the missiles isn’t enough. The data must reach the ground in order to be useful. The SDA’s architecture includes a separate fleet of small communications satellites to relay data from the missile tracking network, and potentially surveillance spacecraft tracking other kinds of moving targets, to military forces on land, at sea, or in the air through a series of inter-satellite laser crosslinks.

The military refers to this data relay component as the transport layer. When it was established in the first Trump administration, the SDA set out to deploy tranches of tracking and data transport satellites. Each new tranche would come online every couple of years, allowing the Pentagon to tap into new technologies as fast as industry develops them.

The SDA launched 27 so-called “Tranche 0” satellites in 2023 to demonstrate the concept’s overall viability. The first batch of more than 150 operational SDA satellites, called Tranche 1, is due to begin launching later this year. The SDA plans to begin deploying more than 250 Tranche 2 satellites in 2027. Another set of satellites, Tranche 3, would have followed a couple of years later. Now, the Pentagon seeks to cancel the Tranche 3 transport layer, while retaining the Tranche 3 tracking layer under the umbrella of the Space Development Agency.

Out of the shadows

While SpaceX’s role isn’t mentioned explicitly in the Pentagon’s budget documents, the MILNET program is already on the books, and SpaceX is the lead contractor. It has been made public in recent months, after years of secrecy, although many details remain unclear. Managed in a partnership between the Space Force and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), MILNET is designed to use military-grade versions of Starlink Internet satellites to create a “hybrid mesh network” the military can rely on for a wide range of applications.

The military version of the Starlink platform is called Starshield. SpaceX has already launched nearly 200 Starshield satellites for the NRO, which uses them for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions.

At an industry conference last month, the Space Force commander in charge of operating the military’s communications satellites revealed new information about MILNET, according to a report by Breaking Defense. The network uses SpaceX-made user terminals with additional encryption to connect with Starshield satellites in orbit.

Col. Jeff Weisler, commander of a Space Force unit called Delta 8, said MILNET will comprise some 480 satellites operated by SpaceX but overseen by a military mission director “who communicates to the contracted workforce to execute operations at the timing and tempo of warfighting.”

The Space Force has separate contracts with SpaceX to use the commercial Starlink service. MILNET’s dedicated constellation of more secure Starshield satellites is separate from Starlink, which now has more 7,000 satellites in space.

“We are completely relooking at how we’re going to operate that constellation of capabilities for the joint force, which is going to be significant because we’ve never had a DoD hybrid mesh network at LEO,” Weisler said last month.

So, the Pentagon already relies on SpaceX’s communication services, not to mention the company’s position as the leading launch provider for Space Force and NRO satellites. With MILNET’s new role as a potential replacement for the Space Development Agency’s data relay network, SpaceX’s satellites would become a cog in combat operations.

Gen. Chance Saltzman, chief of Space Operations in the US Space Force, looks on before testifying before a House Defense Subcommittee on May 6, 2025. Credit: Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

The data transport layer, whether it’s SDA’s architecture or a commercial solution like Starshield, will “underpin” the Pentagon’s planned Golden Dome missile defense system, Saltzman said.

But it’s not just missiles. Data relay satellites in low-Earth orbit will also have a part in the Space Force’s initiatives to develop space-based platforms to track moving targets on the ground and in the air. Eventually, all Space Force satellites could have the ability to plug into MILNET to send their data to the ground.

A spokesperson for the Department of the Air Force, which includes the Space Force, told Air & Space Forces Magazine that the pLEO, or MILNET, constellation “will provide global, integrated, and resilient capabilities across the combat power, global mission data transport, and satellite communications mission areas.”

That all adds up to a lot of bits and bytes, and the Space Force’s need for data backhaul is only going to increase, according to Col. Robert Davis, head of the Space Sensing Directorate at Space Systems Command.

He said the SDA’s satellites will use onboard edge processing to create two-dimensional missile track solutions. Eventually, the SDA’s satellites will be capable of 3D data fusion with enough fidelity to generate a full targeting solution that could be transmitted directly to a weapons system for it to take action without needing any additional data processing on the ground.

“I think the compute [capability] is there,” Davis said Tuesday at an event hosted by the Mitchell Institute, an aerospace-focused think tank in Washington, DC. “Now, it’s a comm[unication] problem and some other technical integration challenges. But how do I do that 3D fusion on orbit? If I do 3D fusion on orbit, what does that allow me to do? How do I get low-latency comms to the shooter or to a weapon itself that’s in flight? So you can imagine the possibilities there.”

The possibilities include exploiting automation, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to sense, target, and strike an enemy vehicle—a truck, tank, airplane, ship, or missile—nearly instantaneously.

“If I’m on the edge doing 3D fusion, I’m less dependent on the ground and I can get around the globe with my mesh network,” Davis said. “There’s inherent resilience in the overall architecture—not just the space architecture, but the overall architecture—if the ground segment or link segment comes under attack.”

Questioning the plan

Military officials haven’t disclosed the cost of MILNET, either in its current form or in the future architecture envisioned by the Trump administration. For context, SDA has awarded fixed-price contracts worth more than $5.6 billion for approximately 340 data relay satellites in Tranches 1 and 2.

That comes out to roughly $16 million per spacecraft, at least an order of magnitude more expensive than a Starlink satellite coming off of SpaceX’s assembly line. Starshield satellites, with their secure communications capability, are presumably somewhat more expensive than an off-the-shelf Starlink.

Some former defense officials and lawmakers are uncomfortable with putting commercially operated satellites in the “kill chain,” the term military officials use for the process of identifying threats, making a targeting decision, and taking military action.

It isn’t clear yet whether SpaceX will operate the MILNET satellites in this new paradigm, but the company has a longstanding preference for doing so. SpaceX built a handful of tech demo satellites for the Space Development Agency a few years ago, but didn’t compete for subsequent SDA contracts. One reason for this, sources told Ars, is that the SDA operates its satellite constellation from government-run control centers.

Instead, the SDA chose L3Harris, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Rocket Lab, Sierra Space, Terran Orbital, and York Space Systems to provide the next batches of missile tracking and data transport satellites. RTX, formerly known as Raytheon, withdrew from a contract after the company determined it couldn’t make money on the program.

The tracking satellites will carry different types of infrared sensors, some with wide fields of view to detect missile launches as they happen, and others with narrow-angle sensors to maintain custody of projectiles in flight. The data relay satellites will employ different frequencies and anti-jam waveforms to supply encrypted data to military forces on the ground.

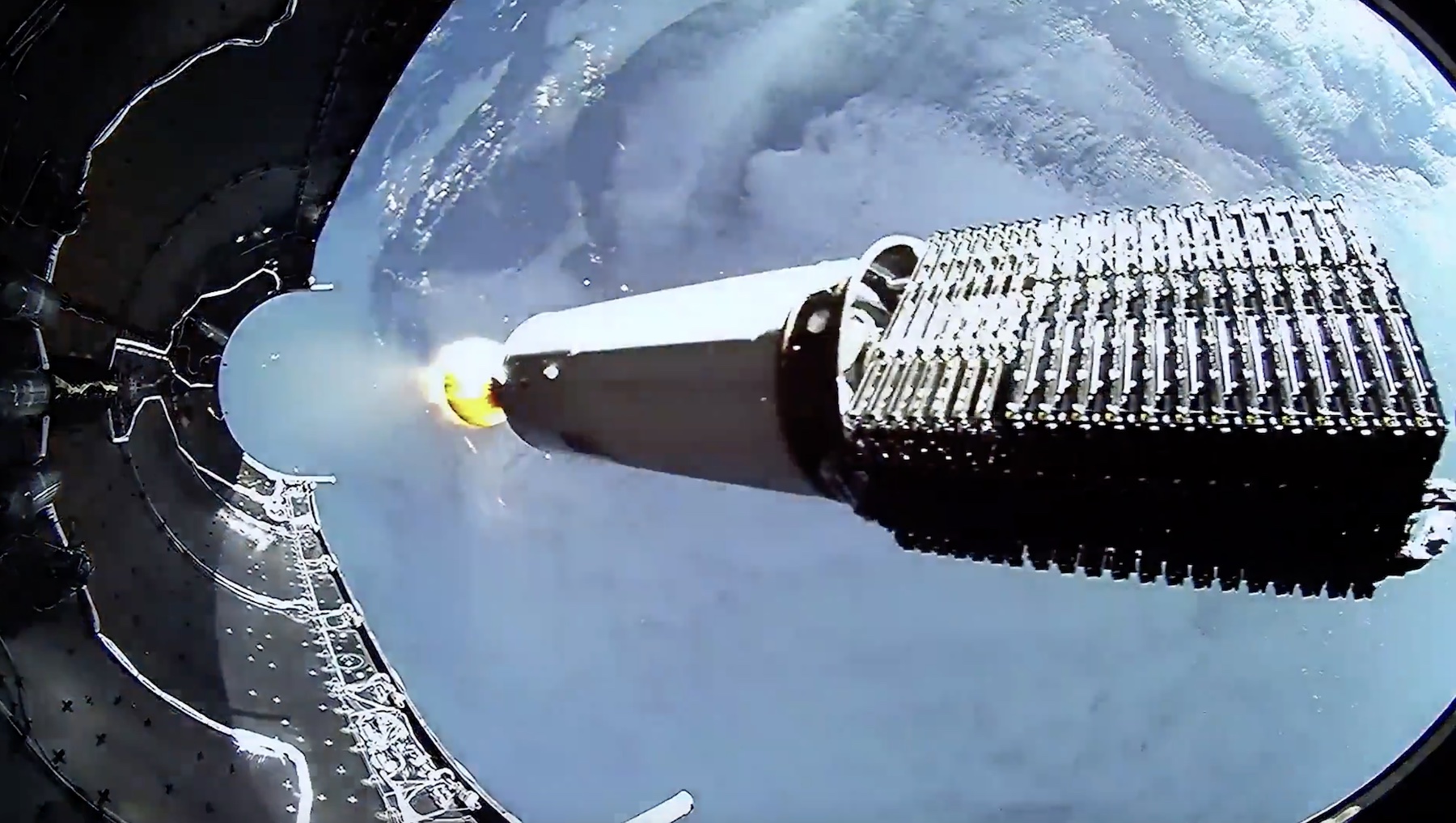

This frame from a SpaceX video shows a stack of Starlink Internet satellites attached to the upper stage of a Falcon 9 rocket, moments after the launcher’s payload fairing is jettisoned. Credit: SpaceX

The Space Development Agency’s path hasn’t been free of problems. The companies the agency selected to build its spacecraft have faced delays, largely due to supply chain issues, and some government officials have worried the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps aren’t ready to fully capitalize on the information streaming down from the SDA’s satellites.

The SDA hired SAIC, a government services firm, earlier this year with a $55 million deal to act as a program integrator with responsibility to bring together satellites from multiple contractors, keep them on schedule, and ensure they provide useful information once they’re in space.

SpaceX, on the other hand, is a vertically integrated company. It designs, builds, and launches its own Starlink and Starshield satellites. The only major components of SpaceX’s spy constellation for the NRO that the company doesn’t build in-house are the surveillance sensors, which come from Northrop Grumman.

Buying a service from SpaceX might save money and reduce the chances of further delays. But lawmakers argued there’s a risk in relying on a single company for something that could make or break real-time battlefield operations.

Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), ranking member of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense, raised concerns that the Space Force is canceling a program with “robust competition and open standards” and replacing it with a network that is “sole-sourced to SpaceX.”

“This is a massive and important contract,” Coons said. “Doesn’t handing this to SpaceX make us dependent on their proprietary technology and avoid the very positive benefits of competition and open architecture?”

Later in the hearing, Sen. John Hoeven (R-N.D.) chimed in with his own warning about the Space Force’s dependence on contractors. Hoeven’s state is home to one of the SDA’s satellite control centers.

“We depend on the Air Force, the Space Force, the Department of Defense, and the other services, and we can’t be dependent on private enterprise when it comes to fighting a war, right? Would you agree with that?” Hoeven asked Saltzman.

“Absolutely, we can’t be dependent on it,” Saltzman replied.

Air Force Secretary Troy Meink said military officials haven’t settled on a procurement strategy. He didn’t mention SpaceX by name.

As we go forward, MILNET, the term, should not be taken as just a system,” Meink said. “How we field that going forward into the future is something that’s still under consideration, and we will look at the acquisition of that.”

An Air Force spokesperson confirmed the requirements and architecture for MILNET are still in development, according to Air & Space Forces Magazine. The spokesperson added that the department is “investigating” how to scale MILNET into a “multi-vendor satellite communication architecture that avoids vendor lock.”

This doesn’t sound all that different than the SDA’s existing technical approach for data relay, but it shifts more responsibility to commercial companies. While there’s still a lot we don’t know, contractors with existing mega-constellations would appear to have an advantage in winning big bucks under the Pentagon’s new plan.

There are other commercial low-Earth orbit constellations coming online, such as Amazon’s Project Kuiper broadband network, that could play a part in MILNET. However, if the Space Force is looking for a turnkey commercial solution, Starlink and Starshield are the only options available today, putting SpaceX in a strong position for a massive windfall.