“We’re going to continue to treat any LOX-methane vehicle with 100 percent TNT blast equivalency.”

Artist’s illustration of Starships stacked on two launch pads at the Space Force’s Space Launch Complex 37 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Credit: SpaceX

The commander of the military unit responsible for running the Cape Canaveral spaceport in Florida expects SpaceX to begin launching Starship rockets there next year.

Launch companies with facilities near SpaceX’s Starship pads are not pleased. SpaceX’s two chief rivals, Blue Origin and United Launch Alliance, complained last year that SpaceX’s proposal of launching as many as 120 Starships per year from Florida’s Space Coast could force them to routinely clear personnel from their launch pads for safety reasons.

This isn’t the first time Blue Origin and ULA have tried to throw up roadblocks in front of SpaceX. The companies sought to prevent NASA from leasing a disused launch pad to SpaceX in 2013, but they lost the fight.

Col. Brian Chatman, commander of a Space Force unit called Space Launch Delta 45, confirmed to reporters on Friday that Starship launches will sometimes restrict SpaceX’s neighbors from accessing their launch pads—at least in the beginning. Space Launch Delta 45, formerly known as the 45th Space Wing, operates the Eastern Range, which oversees launch safety from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and NASA’s nearby Kennedy Space Center.

Chatman’s unit is responsible for ensuring all personnel remain outside of danger areas during testing and launch operations. The range’s responsibility extends to public safety outside the gates of the spaceport.

“There is no better time to be here on the Space Coast than where we are at today,” Chatman said. “We are breaking records on the launch manifest. We are getting capability on orbit that is essential to national security, and we’re doing that at a time of strategic challenge.”

SpaceX is well along in constructing a Starship launch site on NASA property at Kennedy Space Center within the confines of Launch Complex-39A, where SpaceX also launches its workhorse Falcon 9 rocket. The company wants to build another Starship launch site on Space Force property a few miles to the south.

“Early to mid-next year is when we anticipate Starship coming out here to be able to launch,” Chatman said. “We’ll have the range ready to support at that time.”

Enter the Goliath

Starship and its Super Heavy booster combine to form the largest rocket ever built. Its newest version stands more than 400 feet (120 meters) tall with more than 11 million pounds (5,000 metric tons) of combustible methane and liquid oxygen propellants. That will be replaced by a taller rocket, perhaps as soon as 2027, with about 20 percent more propellant onboard.

While there’s also risk with Starships and Super Heavy boosters returning to Cape Canaveral from space, safety officials worry about what would happen if a Starship and Super Heavy booster detonated with their propellant tanks full. The concern is the same for all rockets, which is why officials evacuate predetermined keep-out zones around launch pads that are fueled up for flight.

But the keep-out zones around SpaceX’s Starship launch pads will extend farther than those around the other launch sites at Cape Canaveral. First, Starship is simply much bigger and uses more propellant than any other rocket. Second, Starship’s engines consume methane fuel in combination with liquid oxygen, a blend commonly known as LOX/methane or methalox.

And finally, Starship lacks the track record of older rockets like the Falcon 9, adding a degree of conservatism to the Space Force’s risk calculations. Other launch pads will inevitably fall within the footprint of Starship’s range safety keep-out zones, also known as blast danger areas, or BDAs.

SpaceX’s Starship and Super Heavy booster lift off from Starbase, Texas, in March 2025. Credit: SpaceX

The danger area will be larger for an actual launch, but workers will still need to clear areas closer to Starship launch pads during static fire tests, when the rocket fires its engines while remaining on the ground. This is what prompted ULA and Blue Origin to lodge their protests.

“They understand neighboring operations,” Chatman said in a media roundtable on Friday. “They understand that we will allow the maximum efficiency possible to facilitate their operations, but there will be times that we’re not going to let them go to their launch complex because it’s neighboring a hazardous activity.”

The good news for these other companies is that Eastern Range’s keep-out zones will almost certainly get smaller by the time SpaceX gets anywhere close to 120 Starship launches per year. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 is currently launching at a similar cadence. The blast danger areas for those launches are small and short-lived because the Space Force’s confidence in the Falcon 9’s safety is “extremely high,” Chatman said.

“From a blast damage assessment perspective, specific to the Falcon 9, we know what that keep-out area is,” Chatman said. “It’s the new combination of new fuels—LOX/methane—which is kind of a game-changer as we look at some of the heavy vehicles that are coming to launch. We just don’t have the analysis on those to be able to say, ‘Hey, from a testing perspective, how small can we reduce the BDA and be safe?’”

Methane has become a popular fuel choice, supplanting refined kerosene, liquid hydrogen, or solid fuels commonly used on previous generations of rockets. Methane leaves behind less soot than kerosene, easing engine reusability, and it’s simpler to handle than liquid hydrogen.

Aside from Starship, Blue Origin’s New Glenn and ULA’s Vulcan rockets use liquified natural gas, a fuel very similar to methane. Both rockets are smaller than Starship, but Blue Origin last week unveiled the design of a souped-up New Glenn rocket that will nearly match Starship’s scale.

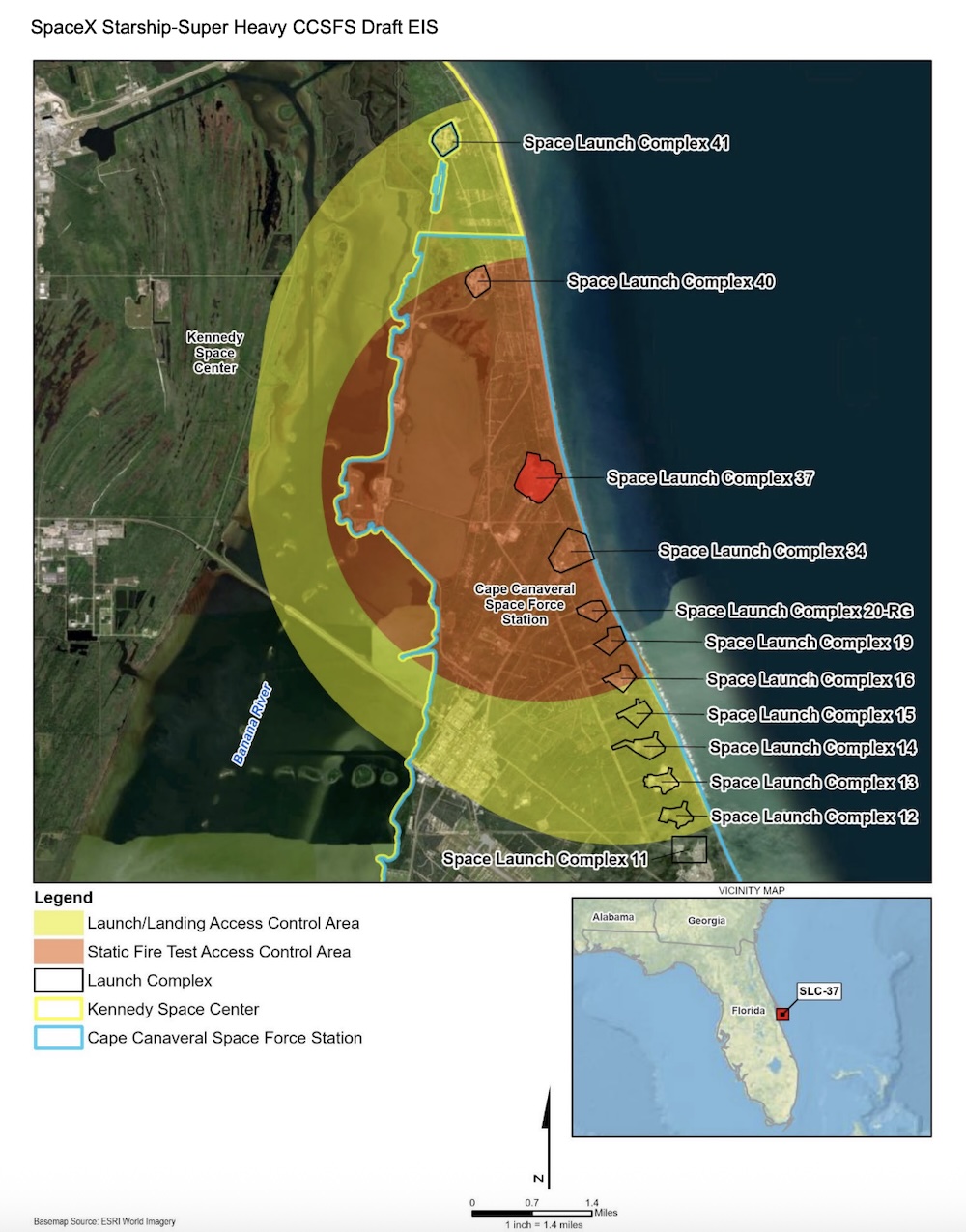

A few years ago, NASA, the Space Force, and the Federal Aviation Administration decided to look into the explosive potential of methalox rockets. There had been countless tests of explosions of gaseous methane, but data on detonations of liquid methane and liquid oxygen was scarce at the time—just a couple of tests at less than 10 metric tons, according to NASA. So, the government’s default position was to assume an explosion would be equivalent to the energy released by the same amount of TNT. This assumption drives the large keep-out zones the Space Force has drawn around SpaceX’s future Starship launch pads, one of which is seen in the map below.

This map from a Space Force environmental impact statement shows potential restricted access zones around SpaceX’s proposed Starship launch site at Space Launch Complex-37. The restricted zones cover launch pads operated by United Launch Alliance, Relativity Space, and Stoke Space. Credit: SpaceX

Spending millions to blow stuff up

Chatman said the Space Force is prepared to update its blast danger areas once its government partners, SpaceX, and Blue Origin complete testing and analyze their results. Over dozens of tests, engineers are examining how methane and liquid oxygen react to different kinds of accidents, such as impact velocity, pressure, and mass ratio, or how much propellant is in the mix.

“That is ongoing currently,” Chatman said. “[We are] working in close partnership with SpaceX and Blue Origin on the LOX/methane combination and the explicit equivalency to identify how much we can … reduce that blast radius. Those discussions are happening, have been happening the last couple years, and are looking to culminate here in ’26.

“Until we get that data from the testing that is ongoing and the analysis that needs to occur, we’re going to continue to treat any LOX-methane vehicle with 100 percent TNT blast equivalency, and have a maximized keep-out zone, simply from a public safety perspective,” Chatman said.

The data so far shows promising results. “We do expect that BDA to shrink,” he said. “We expect that to shrink based on some of the initial testing that has been done and the initial data reviews that have been done.”

That’s imperative, not just for Starship’s neighbors at the Cape Canaveral spaceport, but for SpaceX itself. The company forecasts a future in which it will launch Starships more often than the Falcon 9, requiring near-continuous operations at multiple launch pads.

Chatman mentioned one future scenario in which SpaceX might want to launch Starships in close proximity to one another from neighboring pads.

“At that point in the future, I do anticipate the blast damage assessments to shrink down based on the testing that will have been accomplished and dataset will have been reviewed, [and] that we’ll be in a comfortable set to be able to facilitate all launch operations. But until we have that data, until I’m comfortable with what that data shows, with regards to reducing the BDA, keep-out zone, we’re going to continue with the 100 percent TNT equivalency just from a public safety perspective.”

SpaceX has performed explosive LOX/methane tests, including the one seen here, at its development facility in McGregor, Texas. Credit: SpaceX

The Commercial Space Federation, a lobbying group, submitted written testimony to Congress in 2023 arguing the government should be using “existing industry data” to inform its understanding of the explosive potential of methane and liquid oxygen. That data, the federation said, suggests the government should set its TNT blast equivalency to no greater than 25 percent, a change that would greatly reduce the size of keep-out zones around launch pads. The organization’s members include prominent methane users SpaceX, Blue Origin, Relativity Space, and Stoke Space, all of which have launch sites at Cape Canaveral.

The government’s methalox testing plans were expected to cost at least $80 million, according to the Commercial Space Federation.

The concern among engineers is that liquid oxygen and methane are highly miscible, meaning they mix together easily, raising the risk of a “condensed phase detonation” with “significantly higher overpressures” than rockets with liquid hydrogen or kerosene fuels. Small-scale mixtures of liquid oxygen and liquified natural gas have “shown a broad detonable range with yields greater than that of TNT,” NASA wrote in 2023.

SpaceX released some basic results of its own methalox detonation tests in September, before the government draws its own conclusions on the matter. The company said it conducted “extensive testing” to refine blast danger areas to “be commensurate with the physics of new launch systems.”

Like the Commercial Space Federation, SpaceX said government officials are relying on “highly conservative approaches to establishing blast danger areas, simply because they lack the data to make refined, accurate clear zones. In the absence of data, clear areas of LOX/methane rockets have defaulted to very large zones that could be disruptive to operations.”

More like an airport

SpaceX said it has conducted sub-scale methalox detonation tests “in close collaboration with NASA,” while also gathering data from full-scale Starship tests in Starbase, Texas, including information from test flights and from recent ground test failures. SpaceX controls much of the land around its South Texas facility, so there’s little interruption to third parties when Starships launch from there.

“With this data, SpaceX has been able to establish a scientifically robust, physics-based yield calculation that will help ‘fill the gap’ in scientific knowledge regarding LOX/methane rockets,” SpaceX said.

The company did not disclose the yield calculation, but it shared maps showing its proposed clear areas around the future Starship launch sites at Cape Canaveral and Kennedy Space Center. They are significantly smaller than the clear areas originally envisioned by the Space Force and NASA, but SpaceX says it uses “actual test data on explosive yield and include a conservative factor of safety.”

The proposed clear distances will have no effect on any other operational launch site or on traffic on the primary north-south road crossing the spaceport, the company said. “SpaceX looks forward to having an open, honest, and reasonable discussion based on science and data regarding spaceport operations with industry colleagues.”

SpaceX will have that opportunity next month. The Space Force and NASA are convening a “reverse industry day” in mid-December during which launch companies will bring their ideas for the future of the Cape Canaveral spaceport to the government. The spaceport has hosted 101 space launches so far this year, an annual record dominated by SpaceX’s rapid-fire Falcon 9 launch cadence.

Chatman anticipates about the same number—perhaps 100 to 115 launches—from Florida’s Space Coast next year, and some forecasts show 300 to 350 launches per year by 2035. The numbers could go down before they rise again. “As we bring on larger lift capabilities like Starship and follow-on large launch capabilities out here to the Eastern Range, that will reduce the total number of launches, because we can get more mass to orbit with heavier lift vehicles,” Chatman said.

Blue Origin’s first recovered New Glenn booster returned to the company’s launch pad at Cape Canaveral, Florida, last week after a successful launch and landing. Credit: Blue Origin

Launch companies have some work to do to make those numbers become real. Space Force officials have identified their own potential bottlenecks, including a shortage of facilities for preparing satellites for launch and the flow of commodities like propellants and high-pressure gases into the spaceport.

Concerns as mundane as traffic jams are now enough of a factor to consider using automated scanners at vehicle inspection points and potentially adding a dedicated lane for slow-moving transporters carrying rocket boosters from one place to another across the launch base, according to Chatman. This is becoming more important as SpaceX, and now Blue Origin, routinely shuttle their reusable rockets from place to place.

Space Force officials largely attribute the steep climb in launch rates at Cape Canaveral to the launch industry’s embrace of automated self-destruct mechanisms. These pyrotechnic devices have largely replaced manual flight termination systems, which require ground support from a larger team of range safety engineers, including radar operators and flight control officers with the authority to send a destruct command to the rocket if it flies off course. Now, that is all done autonomously on most US launch vehicles.

The Space Force mandated that launch companies using military spaceports switch to autonomous safety systems by October 1 2025, but military officials issued waivers for human-in-the-loop destruct devices to continue flying on United Launch Alliance’s Atlas V rocket, NASA’s Space Launch System, and the US Navy’s ballistic missile fleet. That means those launches will be more labor-intensive for the Space Force, but the Atlas V is nearing retirement, and the SLS and the Navy only occasionally appear on the Cape Canaveral launch schedule.

Listing image: SpaceX