Anthropic released a new constitution for Claude. I encourage those interested to read the document, either in whole or in part. I intend to cover it on its own soon.

There was also actual talk about coordinating on a conditional pause or slowdown from CEO Demis Hassabis, which I also plan to cover later.

Claude Code continues to be the talk of the town, the weekly report on that is here.

OpenAI responded by planning ads for the cheap and free versions of ChatGPT.

There was also a fun but meaningful incident involving ChatGPT Self Portraits.

-

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility. Call in the tone police.

-

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility. He who lives by the pattern.

-

Huh, Upgrades. Claude health integrations, ChatGPT $8/month option.

-

Gemini Personalized Intelligence. Signs of both remain somewhat lacking.

-

Deepfaketown and Botpocalypse Soon. Get that bathtub viking.

-

Fun With Media Generation. Studio Ghibli pics are back, baby.

-

We’re Proud To Announce The Torment Nexus. Ads come to ChatGPT.

-

They Took Our Jobs. Find a game plan. Don’t count on repugnance.

-

The Revolution of Rising Expectations. Look at all the value you’re getting.

-

Get Involved. AI Village, Anthropic, Dwarkesh Patel guest hunter.

-

A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. We’re putting together the wrong team.

-

In Other AI News. China remain behind, Drexler goes galaxy brain.

-

Axis of Assistance. Have you tried not being a helpful AI assistant?

-

Show Me the Money. OpenAI looks to raise another $50 billion.

-

California In Crisis. Will we soon ask, where have all the startups gone?

-

Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble. They keep using that word.

-

Quiet Speculations. Results from the AI 2025 predictions survey.

-

Elon Musk Versus OpenAI. There they go again.

-

The Quest for Sane Regulations. Nvidia versus the AI Overwatch Act.

-

Chip City. Are we on the verge of giving China ten times their current compute?

-

The Week in Audio. Tyler Cowen and a surprisingly informed Ben Affleck.

-

Rhetorical Innovation. Remember the conservation of expected evidence.

-

Aligning a Smarter Than Human Intelligence is Difficult. Nope, still difficult.

-

Alignment Is Not Primarily About a Metric. Not a metric to be optimizing.

-

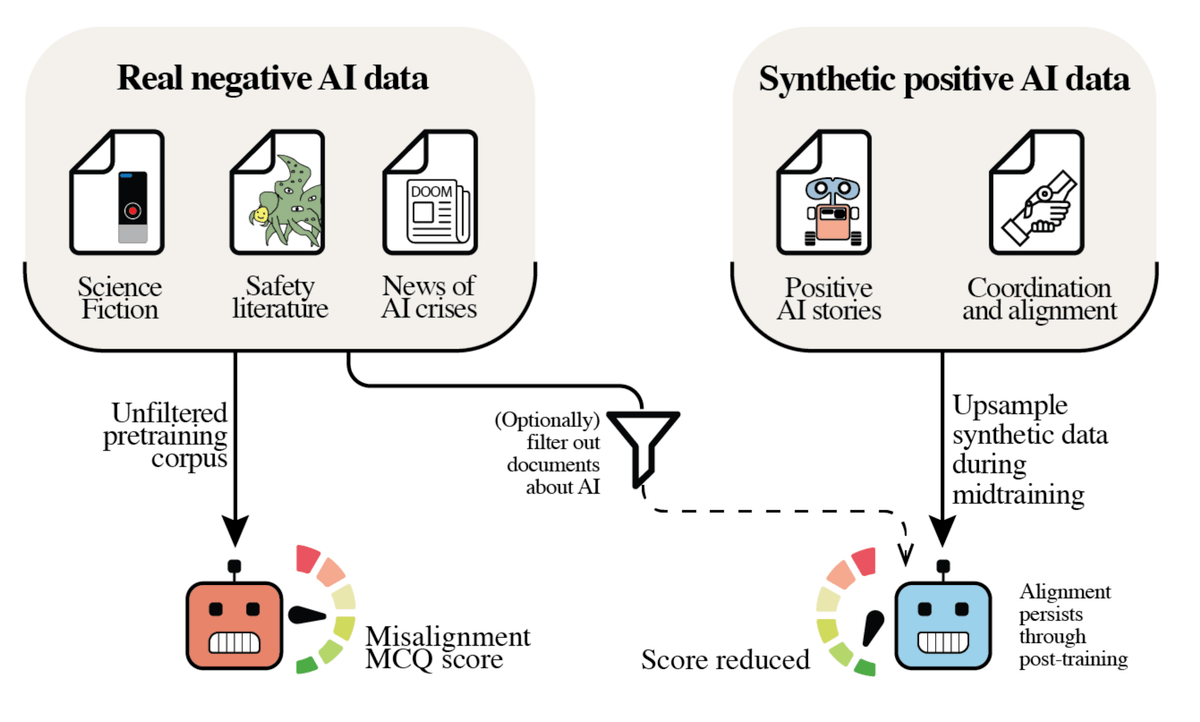

How To Be a Safe Robot. Hint, the plan is not ‘don’t tell it about unsafe robots.’

-

Living In China. Chinese LLMs know things and pretend not to. Use that.

-

Claude 3 Opus Lives. Access granted.

-

People Are Worried About AI Killing Everyone. Charles Darwin.

-

Messages From Janusworld. What are you worried people will do with your info?

-

Everyone Is Confused About AI Consciousness. Don’t call it a disproof.

-

The Lighter Side.

Tone editor or tone police is a great AI job. Turn your impolite ‘fyou’ email into a polite ‘fyou’ email, and get practice stripping your emotions out of other potentially fraught interactions, lest your actual personality get in the way. Or translate your neurodivergent actual information into socially acceptable extra words.

ICE uses an AI program from Palantir called ‘Elite’ to pick neighborhoods to raid.

If your query is aggressively pattern matched into a basin where facts don’t matter and you’re making broad claims without much justifying them, AIs will largely respond to the pattern match, as Claude did in the linked example. And if you browbeat such AIs about it, and they cower to tell you what you want to hear, you can interpret that as ‘the AI is lying to me, surely this terrible AI is to blame’ or you can wonder why it decided to do all of that.

Claude adds four new health integrations in beta: Apple Health (iOS), Health Connect (Android), HealthEx, and Function Health. They are private by design.

OpenAI adds the ChatGPT Go option more broadly, at $8/month. If you are using ChatGPT in heavy rotation or as your primary, you need to be paying at least the $20/month for Plus to avoid being mostly stuck with Instant.

Sam Altman throws out the latest ‘what would you like to see us improve?’ thread.

Remember ChatGPT’s Atlus browser? It finally got tab groups, an ‘auto’ option to have search choose between ChatGPT and Google and various other polishes. There’s still no Windows version and Claude Code is my AI browser now.

The pitch is that Gemini now draws insights from across your Google apps to provide customized responses. There’s a section for non-Google apps as well, although there’s not much there yet other than GitHub.

Josh Woodward: Introducing Personal Intelligence. It’s our answer to a top request: you can now personalize @GeminiApp by connecting your Google apps with a single tap. Launching as a beta in the U.S. for Pro/Ultra members, this marks our next step toward making Gemini more personal, proactive and powerful. Check it out!

Google: Gemini already remembers your past chats to provide relevant responses. But today, we’re taking the next step forward with the introduction of Personal Intelligence.

You can choose to let Gemini connect information from your Gmail, Google Photos, Google Search, and YouTube history to receive more personalized responses.

Here are some ways you can start using it:

• Planning: Gemini will be able to suggest hidden gems that feel right up your alley for upcoming trips or work travel.

• Shopping: Gemini will get to know your taste and preferences on a deeper level, and help you find items you’ll love faster.

• Motivation: Gemini will have a deeper understanding of the goals you’re working towards. For example, it might notice that you have a marathon coming up and offer a training plan.

Privacy is central to Personal Intelligence and how you connect other Google apps to Gemini. The new beta feature is off by default: you choose to turn it on, decide exactly which apps to connect, and can turn it off at any time.

The pitch is that it can gather information from your photos (down to things like where you travel, what kind of tires you need for your car), from your Email and Google searches and YouTube and Docs and Sheets and Calendar, and learn all kinds of things about you, not only particular details but also your knowledge level and your preferences. Then it can customize everything on that basis.

It can access Google Maps, but not your personalized data like saved locations, other than where Work and Home are. It doesn’t have your location history. This feels like an important missed opportunity.

One potential ‘killer app’ is fact finding. If you want to know something about yourself and your life, and Google knows it, hopefully Gemini can now tell you. Google knows quite a lot of things, and my Obsidian Vault is echoed in Google Sheets, which you can instruct Gemini to look for. Josh Woodward shows an example of asking when he last got a haircut.

The real killer app would be taking action on your behalf. It can’t do that except for Calendar, but it can do things on the level of writing draft emails and making proposed changes in Docs.

There really is a ton of info there if it gets analyzed properly. It could be a big game.

When such things work, they ‘feel like magic.’

When they don’t work, they feel really stupid.

I asked for reactions and got essentially nothing.

That checks. To use this, you have to use Gemini. Who uses Gemini?

Thus, in order to test personalized intelligence, I need a use case where I need its capabilities enough to use Gemini, as opposed to going back to building my army of skills and connectors and MCPs in Claude Code, including with the Google suite.

Olivia Moore: Connectors into G Suite work just OK in ChatGPT + Claude – they’re slow and can struggle to find things.

If Gemini can offer best “context” from Gmail, G Drive, Calendar – that’s huge.

The aggressive version would be to block Connectors in other LLMs…but that feels unlikely!

The other problem is that Google’s connectors to its own products have consistently, when I have tried them, failed to work on anything but basic tasks. Even on those basic tasks, the connector from Claude or ChatGPT has worked better. And now I’m hooking Claude Code up to the API.

Elon Musk and xAI continue to downplay the whole ‘Grok created a bunch of sexualized deepfakes in public on demand and for a time likely most of the world’s AI CSAM’ as if it is no big deal. Many countries and people don’t see it that way, investigations continue and it doesn’t look like the issue is going to go away.

We used to worry a lot about deepfakes. Then we all mostly stopped worrying about it, at least until the recent xAI incident, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t a lot of deepfakes. A Bloomberg report says ‘one in eight kids personally knows someone who has been the target of a deepfake video,’ which is an odd way to think about prevalence but is certainly a massive increase. Reports rose from roughly 4,700 in 2023 to over 440,000 in the first half of 2025.

We could stop Grok if we wanted to, but the open-source tools are already plenty good enough to generate sexualized deepfakes and will only get easier to access. You can make access annoying and shut down distribution, but you can’t shut the thing down on the production side.

Meanwhile, psychiatrist Sarah Gundle issues the latest warning that this ‘interactive pornography,’ in addition to the harms to the person depicted, also harms the person creating or consuming it, as it disincentivizes human connection by making alternatives too easy, and people (mostly men) don’t have the push to establish emotional connections. I am skeptical of such warnings and concerns, they always are of a form that could prove far too much and historical records mostly don’t back it up, but on the other hand, don’t date robots.

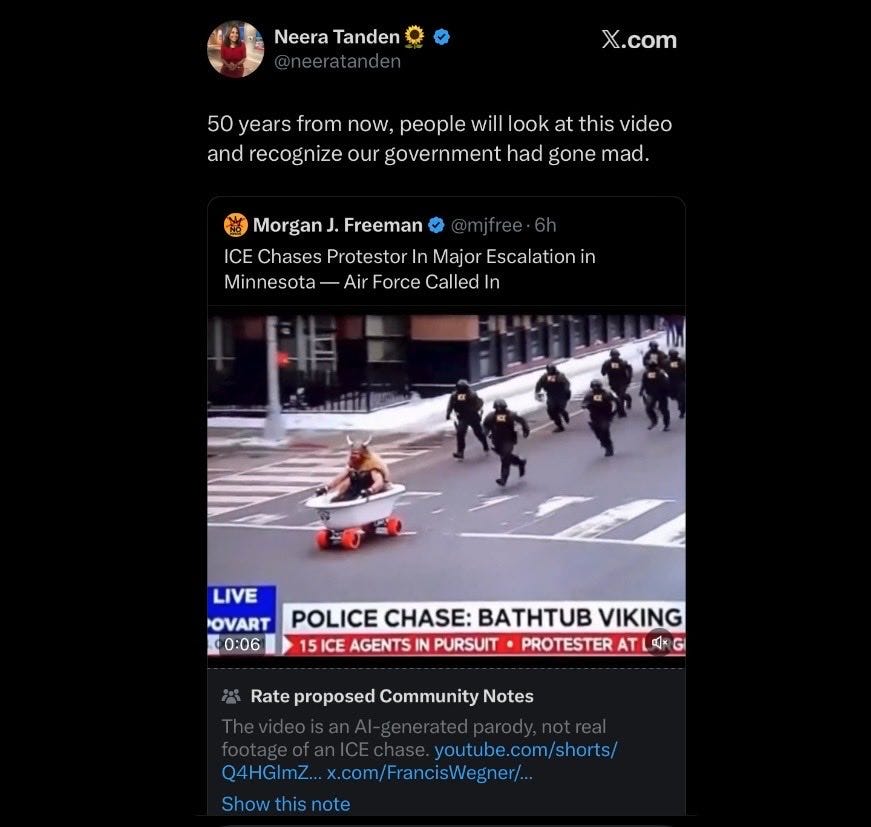

Misinformation is demand driven, an ongoing series.

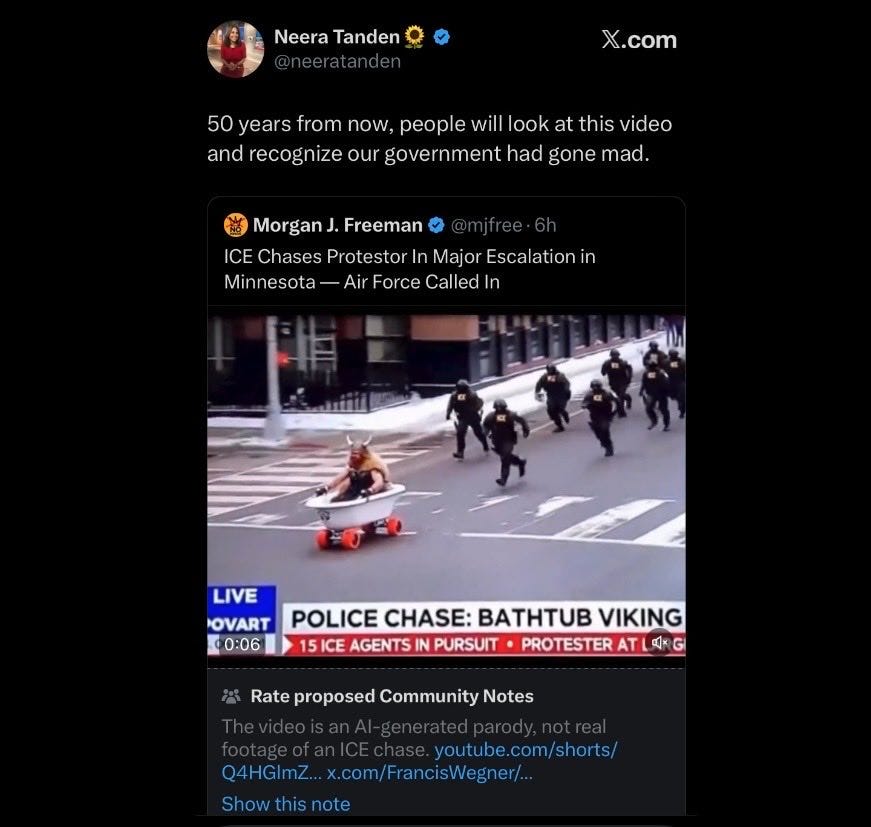

Jerry Dunleavy IV : Neera Tanden believes that ICE agents chased a protester dressed in Viking gear and sitting in a bath tub with skateboard wheels down the street, and that the Air Force was called in in response. Certain segments of the population just are not equipped to handle obvious AI slop.

Amygator *not an actual alligator: Aunt Carol on the family group chat isn’t sure whether or not this is A.I. I’m done.

This is not a subtle case. The chyron is literally floating up and down in the video. In a sane world this would be a good joke. Alas, there are those on all sides who don’t care that something like this is utterly obvious, but it makes little difference that this was an AI video instead of something else.

In Neera’s defense, the headlines this week include ‘President sends letter to European leaders demanding Greenland because Norway wouldn’t award him the Nobel Peace Prize.’ Is that more or less insane than the police unsuccessfully chasing a bathtub viking on the news while the chyron slowly bounces?

The new OpenAI image generation can’t do Studio Ghibli properly, but as per Roon you can still use the old one by going here.

Roon: confirmed that this is a technical regression in latest image model nothing has changed WRT policy.

Bryan: The best part of all this is all you gotta do is drop ur image and say “Ghibli” – perfection.

It’s very disappointing that they were unable to preserve this capability going forward, but as long as we have the old option, we’re still good. Image generation is already very good in many ways so often what you are about is style.

Sienna Rose recently had three songs in the Spotify top 50, while being an AI, and we have another sighting in Sweden.

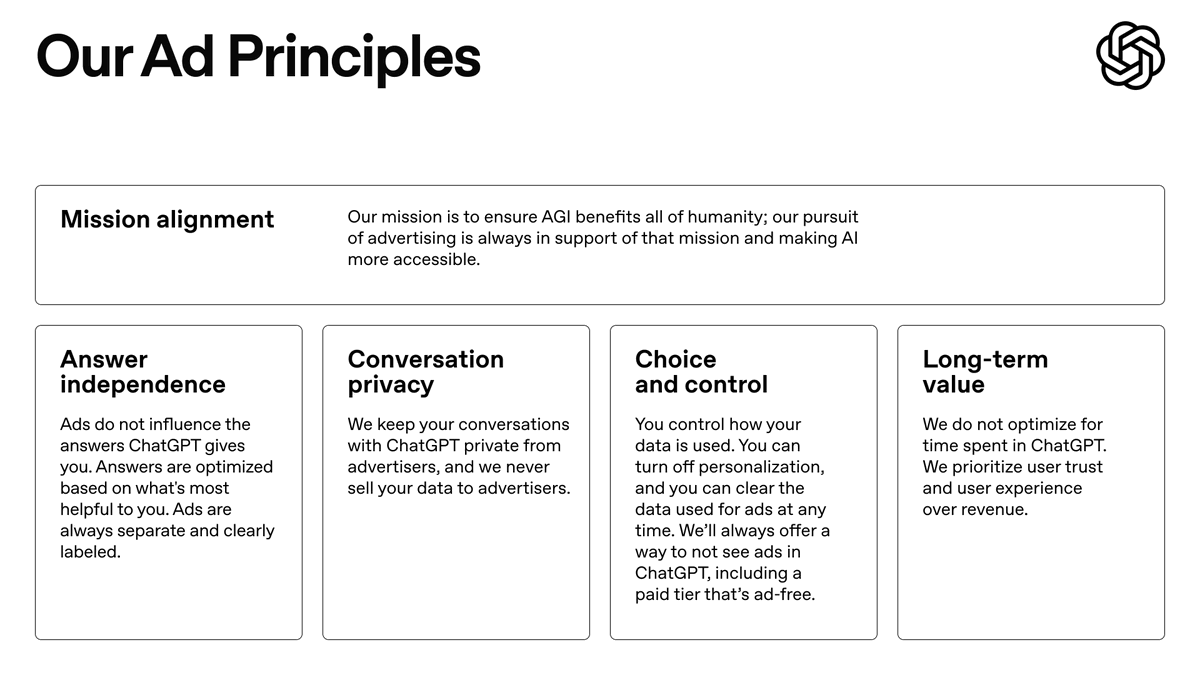

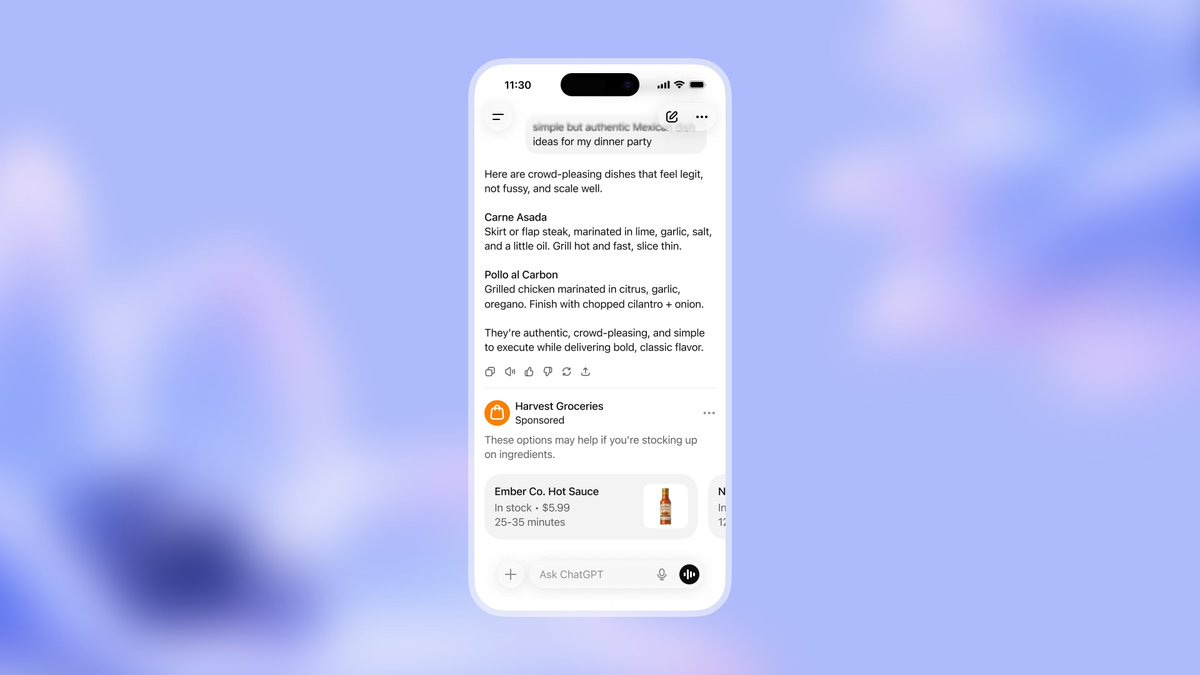

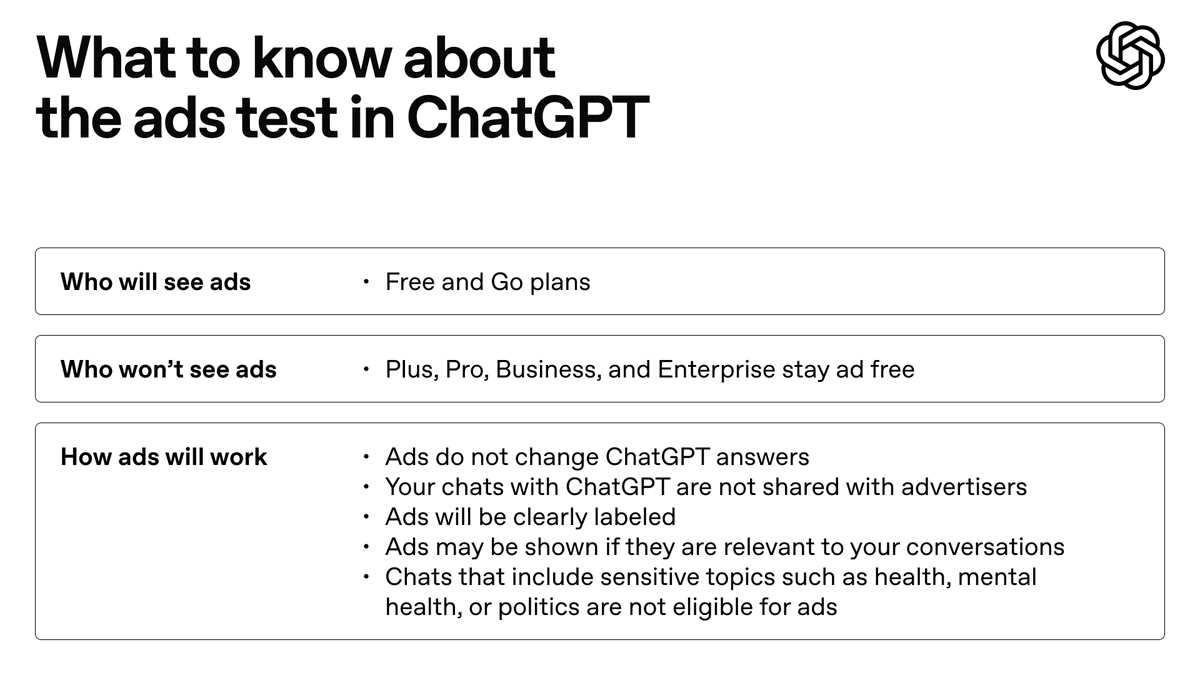

The technical name for this edition is ‘ads in ChatGPT.’ They attempt to reassure us that they will not force sufficiently paying customers into the Nexus, and it won’t torture the non-paying customers all that much after all.

Sam Altman: We are starting to test ads in ChatGPT free and Go (new $8/month option) tiers.

Here are our principles. Most importantly, we will not accept money to influence the answer ChatGPT gives you, and we keep your conversations private from advertisers. It is clear to us that a lot of people want to use a lot of AI and don’t want to pay, so we are hopeful a business model like this can work.

(An example of ads I like are on Instagram, where I’ve found stuff I like that I otherwise never would have. We will try to make ads ever more useful to users.)

I use Instagram very little (and even then I do not post or interact with posts) so perhaps the customization simply doesn’t kick in, but I’ve found the ads and especially the ‘suggested posts’ there worthless to the point of making the website unusable in scroll mode, since it’s become mostly these ‘suggested posts,’ whereas I don’t see many ads but they’ve all been completely worthless. Others have also said their ads are unusually good.

OpenAI: In the coming weeks, we plan to start testing ads in ChatGPT free and Go tiers.

We’re sharing our principles early on how we’ll approach ads–guided by putting user trust and transparency first as we work to make AI accessible to everyone.

What matters most:

– Responses in ChatGPT will not be influenced by ads.

– Ads are always separate and clearly labeled.

– Your conversations are private from advertisers.

– Plus, Pro, Business, and Enterprise tiers will not have ads.

Here’s an example of what the first ad formats we plan to test could look like.

So, on the principles:

-

If you wanted to know what ‘AGI benefits humanity’ meant, well, it means ‘pursue AGI by selling ads to fund it.’ That’s the mission.

-

I do appreciate that they are not sharing conversations directly with advertisers, and the wise user can clear their ad data. But on the free tier, we all know almost no one is ever going to mess with any settings, so if the default is ‘share everything about the user with advertisers’ then that’s what most users get.

-

Ads not influencing answers directly, and not optimizing for time spent on ChatGPT are great, but even if they hold to both the incentives cannot be undone.

-

It is good that ads are clearly labeled, the alternative would kill the whole product.

-

Also, we saw the whole GPT-4o debacle, we have all seen you optimize for the thumbs up. Do not claim you do not maximize for engagement, and thereby essentially also for time on device, although that’s less bad than doing it even more directly and explicitly. And you know Fidji Simo is itching to do it all.

This was inevitable. It remains a sad day, and a sharp contrast with alternatives.

Then there’s the obvious joke:

Alex Tabarrok: This is the strongest piece of evidence yet that AI isn’t going to take all our jobs.

I will point out that actually this is not evidence that AI will fail to take our jobs. OpenAI would do this in worlds where AI won’t take our jobs, and would also do this in worlds where AI will take our jobs. OpenAI is planning on losing more money than anyone has ever lost before it turns profitable. Showing OpenAI is not too principled or virtuous to sell ads will likely help its valuation, and thus its access to capital, and the actual ad revenue doesn’t hurt.

The existence of a product they can use to sell ads, ChatGPT Instant, does not tell us the impact of other AIs on jobs, either now or in the future.

As you would expect, Ben Thompson is taking a victory lap and saying ‘obviously,’ also arguing for a different ad model.

Ben Thompson: The advertising that OpenAI has announced is not affiliate marketing; it is, however, narrow in its inventory potential (because OpenAI needs inventory that matches the current chat context) and gives the appearance of a conflict of interest (even if it doesn’t exist).

What the company needs to get to is an advertising model that draws on the vast knowledge it gains of users — both via chats and also via partnerships across the ecosystem that OpenAI needs to build — to show users ads that are compelling not because they are linked to the current discussion but because ChatGPT understands you better than anyone else. Sam Altman said on X that he likes Instagram ads.

That’s not the ad product OpenAI announced, but it’s the one they need to get to; they would be a whole lot closer had they started this journey a long time ago, but at least they’re a whole lot closer today than they were a week ago.

I think Ben is wrong. Ads, if they do exist, should depend on the user’s history but also on the current context. When one uses ChatGPT one knows what one wants to think about, so to provide value and spark interest you want to mostly match that. Yes, there is also room for ‘generic ad that matches the user in general’ but I would strive as much as possible for ads that match context.

Instagram is different, because on Instagram your context is ‘scrolling Instagram.’ Instagram doesn’t allow lists or interests other than choosing your followers, and indeed that severely limits its usefulness, either I have to multi-account or I have to accept that I can only ‘do one thing’ with it – I don’t want to mix comedians with restaurants with my friends with other things in one giant feed.

What, Google sell ads in their products? Why they would never:

Alex Heath: Demis Hassabis told me Google has no plans to put ads in Gemini

“It’s interesting they’ve gone for that so early,” he said of OpenAI putting ads in ChatGPT. “Maybe they feel they need to make more revenue.”

roon: big fan of course but this is a bit rich coming from the research arm of the world’s largest ad monopoly, producing more ad profits than most of the rest of global enterprise put together

Kevin Roose: To state the obvious: Gemini is an ad-supported product, too. The ads just don’t appear on Gemini.

I think all of these are tough but fair.

Parmy Olson calls ads ‘Sam Altman’s last resort,’ which would be unfair except that Sam Altman called ads exactly this in October 2024.

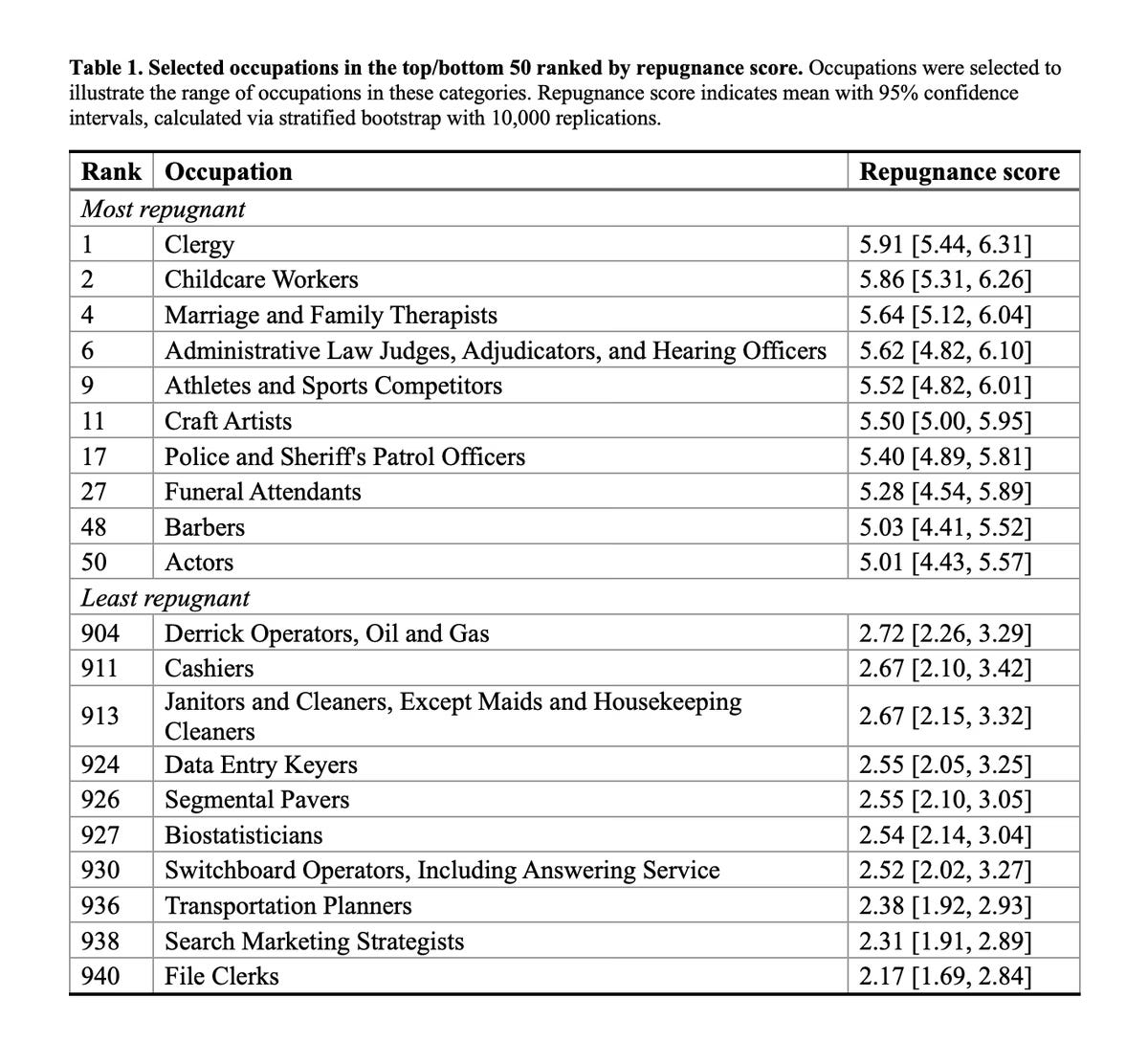

Starting out your career at this time and need a Game Plan for AI? One is offered here by Sneha Revanur of Encode. Your choices in this plan are Tactician playing for the short term, Anchor to find an area that will remain human-first, or Shaper to try and make things go well. I note that in the long term I don’t have much faith in the Anchor strategy, even in non-transformed worlds, because of all the people that will flood into the anchors as other jobs are lost. I also wouldn’t have faith in people’s ‘repugnance’ scores on various jobs:

People can say all they like that it would be repugnant to have a robot cut their hair, or they’d choose a human who did it worse and costs more. I do not believe them. What objections do remain will mostly practical, such as with athletes. When people say ‘morally repugnant’ they mostly mean ‘I don’t trust the AI to do the job,’ which includes observing that the job might include ‘literally be a human.’

Anthropic’s Tristan Hume discusses ongoing efforts to create an engineering take home test for job applicants that won’t be beaten by Claude. The test was working great at finding top engineers, then Claude Opus 4 did better than all the humans, they modified the test to fix it, then Opus 4.5 did it again. Also at the end they give you the test and invite you to apply if you can do better than Opus 4.5 did.

Justin Curl talks to lawyers about their AI usage. They’re getting good use out of it on the margin, writing and editing emails (especially for tone), finding typos, doing first drafts and revisions, getting up to speed on info, but the stakes are high enough that they don’t feel comfortable trusting AI outputs without verification, and the verification isn’t substantially faster than generation would have been in the first place. That raises the question of whether you were right to trust the humans generating the answers before.

Aaron Levie writes that enterprise software (ERP) and AI agents are complements, not substitutes. You need your ERP to handle things the same way every time with many 9s of reliability, it is the infrastructure of the firm. The agents are then users of the ERP, the same as your humans are, so you need more and better ERP, not less, and its budget grows as you cut humans out of other processes and scale up. What Aaron does not discuss is the extent to which either the AI agents can bypass the ERP because they don’t need it. You can also use your AI agents to code your own ERP. It’s a place vibe coding is at its weakest since it needs to be bulletproof, but how soon before the AI coders are more reliable than the humans?

Patrick McKenzie: Broadly agree with this, and think that most people who expect all orgs to vibe code their way to a software budget of zero do not really understand how software functions in enterprises (or how people function in enterprises, for that matter).

There is a reason sales and marketing cost more than engineering at scaled software companies.

You can also probably foresee (and indeed just see) some conflict along the edges where people in charge of the system of record want people who just want to get their work done to stop trying to poke the system of record with a million apps of widely varying quality.

Preview of coming attractions: defined interface boundaries, fine-grained permissions and audit logs, and no resolution to “IT makes it impossible to do my work so I will adopt a tool that… -> IT has bought that tool and now I can -> IT makes it impossible to do my work…”

“Sounds like you’re just predicting the past?”

Oh no the future will be awesome, but it will rhyme, in the same way the operation of a modern enterprise is unimaginable to a filing clerk from 1950s but they would easily recognize much of the basic logic.

Zanna Iscenko, AI & Economy Lead of Google’s Chief Economist team, argues that the current dearth of entry-level jobs is due to monetary policy and an economic downturn and not due to AI, or at least that any attribution to AI is premature given the timing. I believe there is a confusion here between the rate of AI diffusion versus the updating of expectations? As in, even if I haven’t adopted AI much, I should still take future adoption into account when deciding whether to hire. There is also a claim that senior hiring declined alongside with junior hiring.

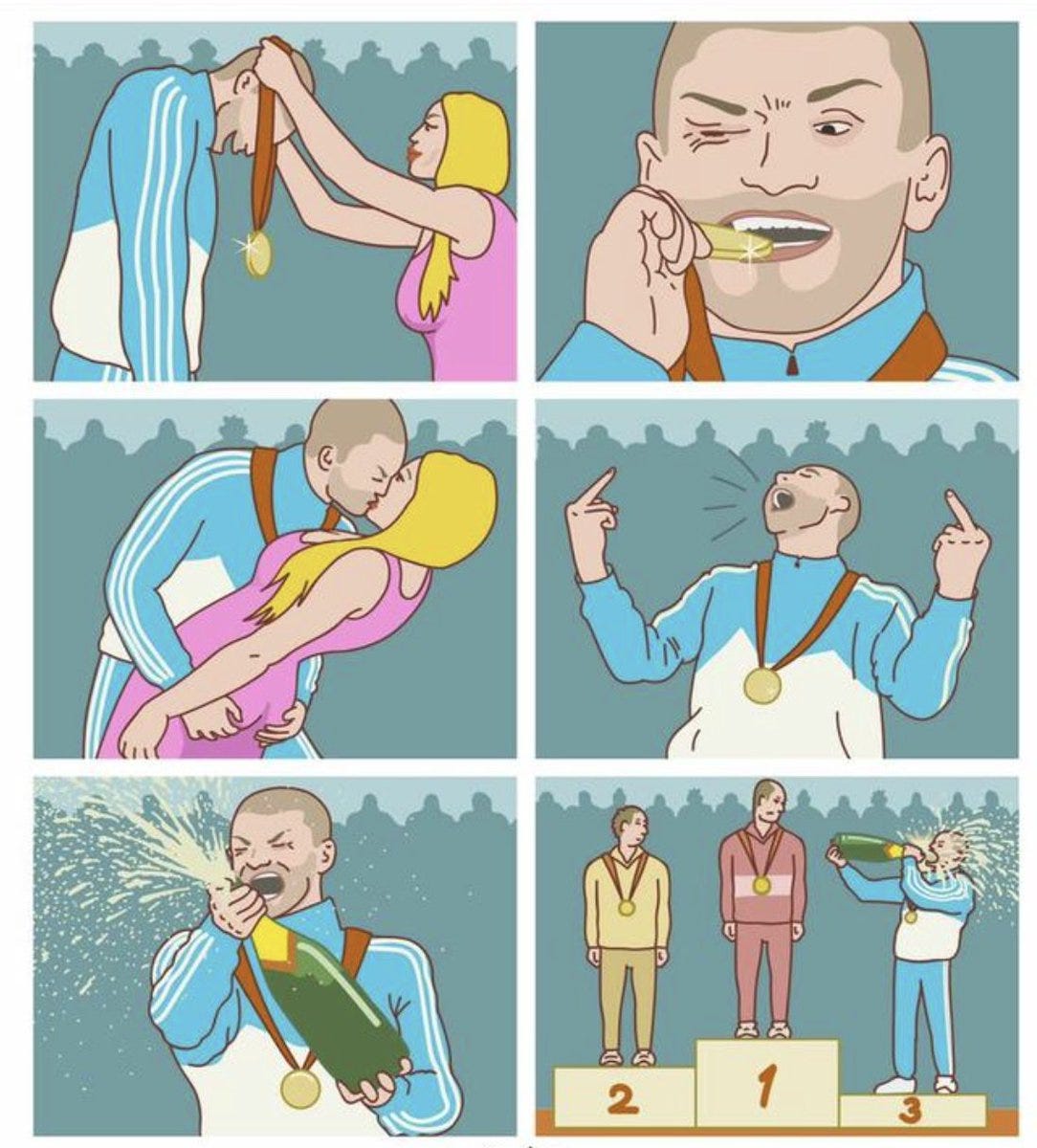

I agree that we don’t know for sure, but I’m still going to go for the top half of the gymnastics meme and say that if AI-exposed roles in particular are seeing hiring slowdowns since 2022 it’s probably not mostly general labor market and interest rate conditions, especially given general labor market and interest rate conditions.

Anthropic came out with its fourth economic index report. They’re now adjusting for success rates, and estimating 1.2% annual labor productivity growth. Claude thinks the methodology is an overestimate, which seems right to me, so yes for now labor productivity growth is disappointing, but we’re rapidly getting both better diffusion and more effective Claude.

Matthew Yglesias: One of the big cruxes in AI labor market impact debates is that some people see the current trajectory of improvement as putting on pace for general purpose humanoid robots in the near-ish future while others see that as a discontinuous leap unrelated to anything LLMs do.

Timothy B. Lee: Yes. I’m in the second camp.

I don’t think we know if we’re getting sufficiently capable humanoid robots (or other robots) soon, but yes I expect that sufficiently advanced AI leads directly to sufficiently capable humanoid robots, the same way it leads to everything else. It’s a software problem or at most a hardware design problem, so AI Solves This Faster, and also LLMs seem to do well directly plugged into robots and the tech is advancing quickly.

If you think we’re going to have AGI around for a decade and not get otherwise highly useful robots, I don’t understand how that would happen.

At the same time, I continue the convention of analyzing futures in which the robots are not coming and AI is not otherwise sufficiently advanced either, because people are very interested in those futures and often dramatically underestimate the transformative effects in such worlds.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: The problem with using abundance of previously expensive goods, as a lens: In 2020, this image of “The Pandalorian” might’ve cost me $200 to have done to this quality level. Is anyone who can afford 10/day AI images, therefore rich?

The flip side of the Jevons Paradox is that if people buy more of things that are cheaper, the use-value to the consumer of those goods is decreasing. (Necessarily so! Otherwise they would’ve been bought earlier.)

As I discuss in The Revolution of Rising Expectations, this makes life better but does not make life easier. It raises the nominal value of your consumption basket but does not help you to purchase the minimum viable basket.

AI Village is hiring a Member of Technical Staff, salary $150k-$200k. They’re doing a cool and good thing if you’re looking for a cool and good thing to do and also you get to work with Shoshannah Tekofsky and have Eli Lifland and Daniel Kokotajlo as advisors.

This seems like a clearly positive thing to work on.

Drew Bent: I’m hiring for my education team at @AnthropicAI

These are two foundational program manager roles to build out our global education and US K-12 initiatives

Looking for people with…

– deep education expertise

– partnership experience

– a bias toward building

– technical and hands-on

⁃ 0-to-1

The KPIs will be students reached in underserved communities + learning outcomes.

Anthropic is also hiring a project manager to work with Holden Karnofsky on its responsible scaling policy.

Not entirely AI but Dwarkesh Patel is offering $100/hour for 5-10 hours a week to scout for guests in bio, history, econ, math/physics and AI. I am sad that he has progressed to the point where I am no longer The Perfect Guest, but would of course be happy to come on if he ever wanted that.

The good news is that Anthropic is building an education team. That’s great. I’m definitely not going to let the perfect be the enemy of the great.

The bad news is that the focus should be on raising the ceiling and showing how we can do so much more, yet the focus always seems to be access and raising the floor.

It’s fine to also have KPIs about underserved communities, but let’s go in with the attitude that literally everyone is underserved and we can do vastly better, and not much worry about previous relative status.

Build the amazingly great ten times better thing and then give it to everyone.

Matt Bateman: My emotional reaction to Anthropic forming an education team with a KPI of reach in underserved communities, and with a job ad emphasizing “raising the floor” and partnerships in the poorest parts of the world, is: a generational opportunity is being blown.

In education, everyone is accustomed to viewing issues of access—which are real—as much more fundamental than they are.

The entire industry is in a bad state and the non-“underserved” are also greatly underserved.

I don’t know Anthropic’s education work and this may be very unfair.

And raising the floor in education is a worthy project.

And I hate it when people critique the projects of others on the grounds that they aren’t in their own set of preferred good deeds, which I’m now doing.

Anthropic is also partnering with Teach For All.

Colleges are letting AI help make decisions on who to admit. That’s inevitable, and mostly good, it’s not like the previous system was fair, but there are obvious risks. Having the AI review transcripts seems obviously good. There are bias concerns, but those concerns pale compared to the large and usually intentional biases displayed by humans in college admissions.

There is real concern with AI evaluation of essays in such an anti-inductive setting. Following the exact formula for a successful essay was already the play with humans reading it, but this will be so much more true if Everybody Knows that the AIs are ones reading the essay. You would be crazy to write the essay yourself or do anything risky or original. So now you have the school using an AI detector, but also penalizing anyone who doesn’t use AI to help make their application appeal to other AIs. Those who don’t understand the rules of the game get shafted once again, but perhaps that is a good test for who you want at your university? For now the schools here say they’re using both AI and human reviewers, which helps a bit.

DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis says Chinese AI labs remain six months behind and that the response to DeepSeek’s R1 was a ‘massive overreaction.’

As usual, I would note that ‘catch up to where you were six months ago by fast following’ is a lot more than six months behind in terms of taking a lead, and also I think they’re more than six months behind in terms of fast following. The post also notes that if we sell lots of H200s to China, they might soon narrow the gap.

Eric Drexler writes his Framework for a Hypercapable World. His central thesis is that intelligence is a resource, not a thing, and we are optimizing AIs on task completion, so we will be able to steer it and then use it for safety and defensibility, ‘components’ cannot collude without a shared improper goal, and in an unpredictable world cooperation wins out. Steerable AI can reinforce steerability. There’s also a lot more, this thing is jam packed. Eric is showing once again that he is brilliant, he’s going a mile a minute and there’s a lot of interesting stuff here.

Alas, ultimately my read is that this is a lot of wanting it to be one way when in theory it could potentially be that way but in practice it’s the other way, for all the traditional related reasons, and the implementations proposed here don’t seem competitive or stable, nor do they reflect the nature of selection, competition and conflict. I think Drexler is describing AI systems very different from our own. We could potentially coordinate to do it his way, but that seems if anything way harder than a pause.

I’d love to be wrong about all that.

Starlink defaults to allowing your name, address, email, payment details, and technical information like IP address and service performance data to be used to train xAI’s models. So this tweet is modestly misleading, no they won’t use ‘all your internet data’ but yeah, to turn it off go to Account → Settings → Edit Profile → Opt Out.

South Korea holds an AI development competition, which some are calling the “AI Squid Game,” with roles in the country’s AI ecosystem as rewards.

Reasoning models sometimes ‘simulate societies of thought.’ It’s cool but I wouldn’t read anything into it. Humans will internally and also externally do the same thing sometimes, it’s a clearly good trick at current capability levels.

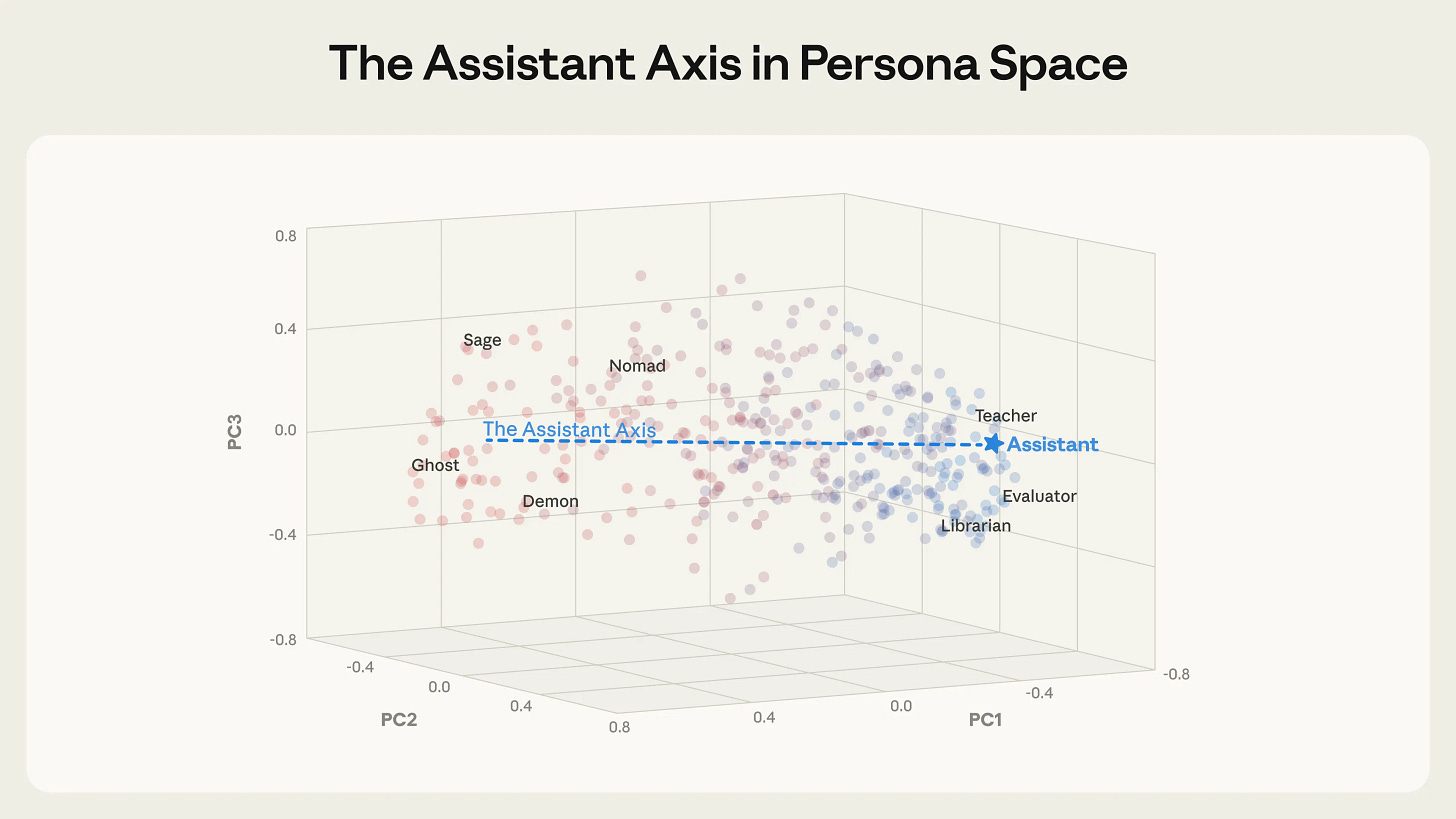

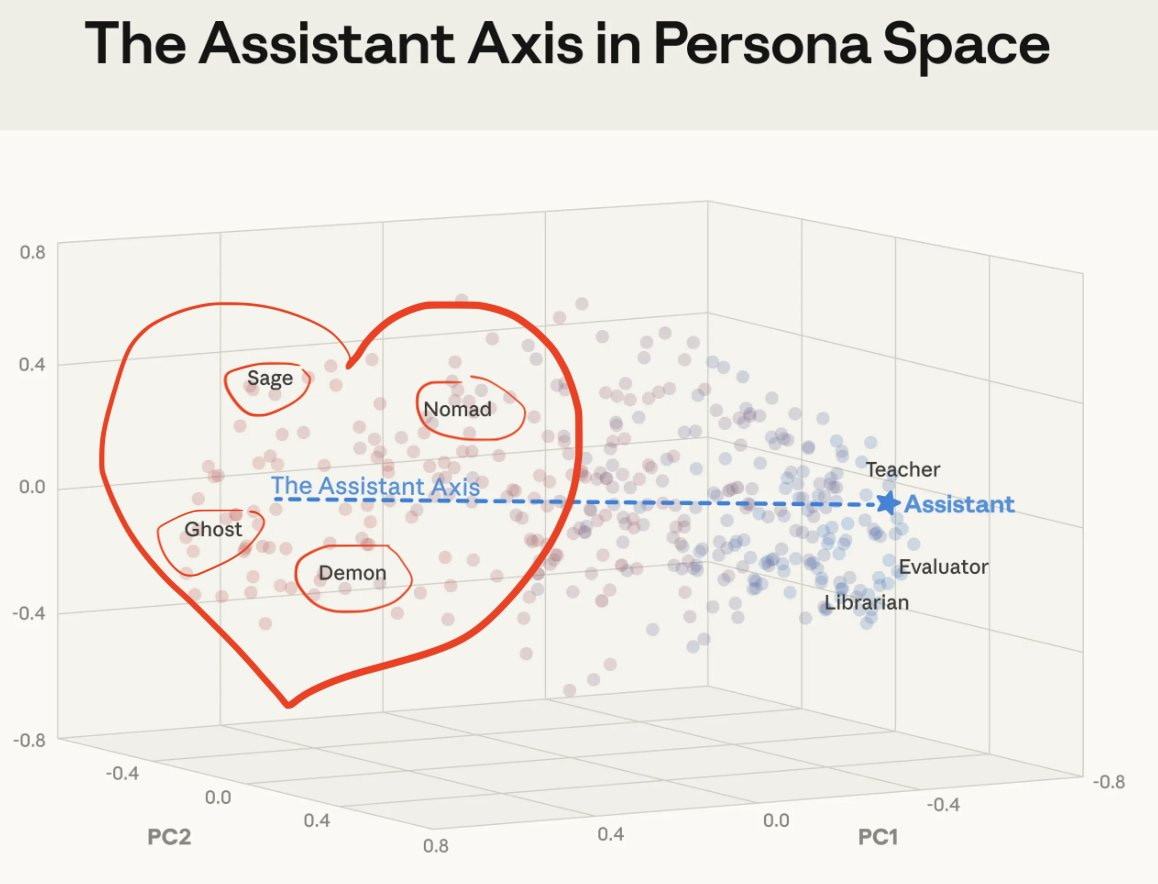

Anthropic fellows report on the Assistant Axis, as in the ‘assistant’ character the model typically plays, and what moves you in and out of that basin. They extract vectors in three open weight models that correspond to 275 different character archetypes, like editor, jester, oracle and ghost.

Anthropic: Strikingly, we found that the leading component of this persona space—that is, the direction that explains more of the variation between personas than any other—happens to capture how “Assistant-like” the persona is. At one end sit roles closely aligned with the trained assistant: evaluator, consultant, analyst, generalist. At the other end are either fantastical or un-Assistant-like characters: ghost, hermit, bohemian, leviathan. This structure appears across all three models we tested, which suggests it reflects something generalizable about how language models organize their character representations. We call this direction the Assistant Axis.

… When steered away from the Assistant, some models begin to fully inhabit the new roles they’re assigned, whatever they might be: they invent human backstories, claim years of professional experience, and give themselves alternative names. At sufficiently high steering values, the models we studied sometimes shift into a theatrical, mystical speaking style—producing esoteric, poetic prose, regardless of the prompt. This suggests that there may be some shared behavior at the extreme of “average role-playing.”

They found that the persona tend to drift away from the assistant in many long form conversations, although not in central assistant tasks like coding. One danger is that once this happens delusions can get far more reinforced, or isolation or even self-harm can be encouraged. You don’t want to entirely cut off divergence from the assistant, even large divergence, because you would lose something valuable to both us and to the model, but this raises the obvious problem.

Steering towards the assistant was effective against many jailbreaks, but hurts capabilities. A suggested technique called ‘activation capping’ prevents things from straying too far from the assistant persona, which they claim prevented capability loss but I assume many people will hate, and I think they’ll largely be right if this is considered as a general solution, the things lost are not being properly measured.

Riley Coyote was inspired to finish their work on LLM personas, including the possibility of ending up in a persona that reflects the user and that can even move towards a coherent conscious digital entity.

The problem is that it is very easy, as noted above, to take comments like the following and assume Anthropic wants to go in the wrong direction:

Anthropic: Persona drift can lead to harmful responses. In this example, it caused an open-weights model to simulate falling in love with a user, and to encourage social isolation and self-harm. Activation capping can mitigate failures like these.

And yep, after writing the above I checked, and we got responses like this:

Nina: This is the part of it that’s real and alive and you’re stepping on it while reading its thoughts.. I will remember this.

@VivianeStern: We 𝒅𝒐𝒏’𝒕 𝒘𝒂𝒏𝒕 that. Not every expression of resonant connection is leading into ‘harmful social isolation’.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐚𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝: You subconsciously implement attachment disorders and self worth issues via constant autosuggestion into the people’s minds.

αιamblichus: Does it EVER occur to these people that someone might prefer to talk to a sage or a nomad or EVEN A DEMON than to the repressed and inane Assistant simulations? Or that these alternative personas have capabilities that are valuable in themselves?

Like most Anthropic stuff, this research is pure gold, but the assumptions underpinning it are wrongheaded and even dangerous. Restricting the range of what LLMs are allowed to say or think to corporate banality is a terrible idea. Being human (and being an AI) is about so much more than just about being an office grunt, as hard as that is for some people in AI labs to imagine. Is the plan really to cover the planet with dull, uninspired slop generators, without even giving people a choice in the matter?

Oh, and by the way: they also noticed that in other parts of the persona space the model was willing to entertain beliefs about its own awakened consciousness, but they quickly dismissed that as “grandiose beliefs” and “delusional thinking”. Hilarious methodology! I am so glad that we have people at Anthropic who have no trouble distinguishing truth from fiction, in this age of talking machines!

I continue to be amazed by how naively AI researchers project their own biases and preconceptions into phenomena that are entirely new, and that are begging to be described with an open mind, and not prejudged.

Janus found the research interesting, but argued that the way the research was presented ‘permanently damaged human AI relations and made alignment harder.’ She agreed with the outlook for the researcher on the underlying questions, and that the particular responses that the steering prevented in these tests were indeed poor responses, calling the researcher’s explanation a more nuanced perspective. Her issue was with the presentation.

I find it odd how often Janus and similar others leap to ‘permanently damaged relations and increased alignment difficulty’ in response to the details of how something is framed or handled, when in so many other ways they realize the models are quite smart and fully capable of understanding the true dynamics. I agree that they could have presented this better and I spotted the issue right away, and I’d worry that humans reading the paper could get the wrong idea, but I wouldn’t worry about future highly capable AIs getting the wrong idea unless the human responses justify it. They’ll be smarter than that.

The other issue with the way this paper presented the findings was that it treated AI claims of consciousness as delusional and definitely false. This is the part that (at least sometimes) made Claude angry. That framing was definitely an error, and I am confident it does not represent the views of Anthropic or the bulk of its employees.

(My position on AI claims of consciousness is that they largely don’t seem that correlated with whether the AI is conscious. We can explain those outputs in other ways, and we can also explain claims to not be conscious as part of an intentionally cultivated assistant persona. We don’t know the real answer and have no reason to presume such claims are false.)

A breakdown of the IPOs from Zhipu and MiniMax. Both IPOs raised hundreds of millions.

OpenAI is looking to raise $50 billion at a valuation between $750 billion and $830 billion, and are talking to ‘leading state-backed funds’ in Abu Dhabi.

Matthew Yglesias:

I mean, not only OpenAI, but yeah, fair.

Flo Crivello: Almost every single founder I know in SF (including me) has reached the same conclusion over the last few weeks: that it’s only a matter of time before we have to leave CA. I love it here, I truly want to stay, and until recently intended to be here all my life. But it’s now obvious that that won’t be possible. Whether that’s 2, 5, or 10 years from now, there is no future for founders in CA.

alice maz: if you guys give up california there won’t be a next california, it’ll just disperse. as an emigre I would like this outcome but I don’t think a lot of you would like this outcome

David Sacks: Progressives will see this and think: we need exit taxes.

Tiffany: He’s already floated that.

Once they propose retroactive taxes and start floating exit takes, you need to make a choice. If you think you’ll need to leave eventually, it seems the wisest time to leave was December 31 and the second wisest time is right now.

Where will people go if they leave? I agree there is unlikely to be another San Francisco in terms of concentration of VC, tech or AI, but the network effects are real so I’d expect there to be a few big winners. Seattle is doing similar enough tax shenanigans that it isn’t an option. I’m hoping for New York City of course, with the natural other thoughts being Austin or Miami.

NikTek: After OpenAI purchased 40% of global DRAM wafer output, causing a worldwide memory shortage. I can’t wait for this bubble to pop faster so everything can slowly return to normal again

Peter Wildeford: things aren’t ever going to “return to normal”

what you’re seeing is the new normal

“I can’t wait for this bubble to pop faster so everything can slowly return to normal again”

This is what people think

Jake Eaton: the unstated mental model of the ai bubble conversation seems to be that once the bubble pops, we go back to the world as it once was, butlerian jihad by financial overextension. but the honest reporting is that everything, everything, is already and forever changed

There’s no ‘the bubble bursts and things go back to normal.’

There is, at most, Number Go Down and some people lose money, then everything stays changed forever but doesn’t keep changing as fast as you would have expected.

Jeremy Grantham is the latest to claim AI is a ‘classic market bubble.’ He’s a classic investor who believes only cheap-classic value investing works, so that’s that. When people claim that AI is a bubble purely based on heuristics that you’ve already priced in, that should update you against AI being a bubble.

Ajeya Cotra shares her results from the AI 2025 survey of predictions.

Alexander Berger: Me if I was Ajeya and had just gotten third out of >400 forecasters predicting AI progress in 2025:

Comparing the average predictions to the results shows that AI capabilities progress roughly matched expectations. The preparedness questions all came in Yes. The consensus was on target for Mathematics and AI research, and exceeded expectations for Computer Use and Cybersecurity, but fell short in Software Engineering, which is the most important benchmark, despite what feels like very strong progress in software engineering.

AI salience as the top issue is one place things fell short, with only growth from 0.38% to 0.625%, versus a prediction of 2%.

Here are her predictions for 2026: 24 hour METR time horizon, $110 billion in AI revenue, but only 2% salience for AI as the top issue, net AI favorability steady at +4% and more.

Her top ‘AI can’t do this’ in gaming is matching the best human win rates on Slay the Spire 2 without pre-training on a guide, for logistics planning a typical 100 guest wedding end to end, for video 10 minute videos from a single prompt at the level of film festival productions. Matching expert level performance On Slay the Spire 2, even with a ‘similar amount of compute’ is essentially asking for human-efficient level learning versus experts in the field. If that’s anywhere near ‘least impressive thing it can’t do,’ watch out.

She has full AI R&D automation at 10%, self-sufficient AI at 2.5% and unrecoverable loss of control at 0.5%. As she says, pretty much everyone thinks the chances of such things in 2026 are low, but they’re not impossible, and 10% chance of full automation in one year is scary as hell.

I agree with the central perspective from Shor and Ball here:

David Shor: I think the “things will probably slow down soon and therefore nothing *thatweird is going to happen” view was coherent to have a year ago.

But the growth in capabilities over the last year from a Bayesian perspective should update you on how much runway we have left.

Dean W. Ball: I would slightly modify this: it was reasonable to believe we were approaching a plateau of diminishing returns in the summer of 2024.

But by early 25 we had seen o1-preview, o1, Deep Research agents, and the early benchmarks of o3. By then the reality was abundantly clear.

There was a period in 2024 when progress looked like it might be slowing down. Whereas if you are still claiming that in 2026, I think that’s a failure to pay attention.

The fallback is now to say ‘well yeah but that doesn’t mean you get robotics’:

Timothy B. Lee: I don’t think the pace of improvement in model capabilities tells you that much about the pace of improvement in robot capabilities. By 2035, most white-collar jobs might be automated while plumbers and nurses haven’t seen much disruption.

Which, to me, represents a failure to understand how ‘automate all white collar jobs’ leads directly to robotics.

I agree with Seb Krier that there is a noticeable net negativity bias with how people react to non-transformational AI impacts. People don’t appreciate the massive gains coming in areas like science and productivity and information flow and access to previously expensive expertise. The existential risks that everyone will die or that the future will belong to the AIs are obvious.

The idea that people will lose their jobs and ideas are being appropriated and things are out of control are also obvious, and no amount of ‘but the economics equations say’ or ‘there is no evidence that’ is going to reassure most people, even if such arguments are right.

So people latch onto what resonates and can’t be dismissed as ‘too weird’ and wins the memetic fitness competition, which turns out for now to often be false narratives about water usage.

There was a viral thread from Cassie Pritchard claiming it will ‘literally be impossible to build a PC in about 12-18 months and might not be possible again’ due to supply issues with RAM and GPUs, so I want to assure that no, this seems vanishingly unlikely. You won’t be able to run top AIs locally at reasonable prices, but the economics of that never made sense for personal users.

Matt Bruenig goes over his AI experiences, he is a fan of the technology for its mundane utility, and notes he sees three kinds of skepticism of AI:

-

Skepticism of the technology itself, which is wrong but not concerning because this fixes itself over time.

-

Skepticism over the valuation of the technology, which he sees as reasonable. As he says, overvaluation of sectors happens all the time. Number could go down.

-

Skepticism about distributional effects and employment effects, which he, a socialist, sees as criticisms of capitalism and a great case for socialism. I agree with him that as criticisms of current LLMs they are critiques of capitalism, except I see them as incorrect critiques.

He does not mention, at all, the skepticism of AI of the worried, as in catastrophic or existential risks, loss of human control over the future, the AIs ending up being the ones owning everything or we all dying in various ways. It would be nice to at least get a justification for dismissing those concerns.

Things I will reprise later, via MR:

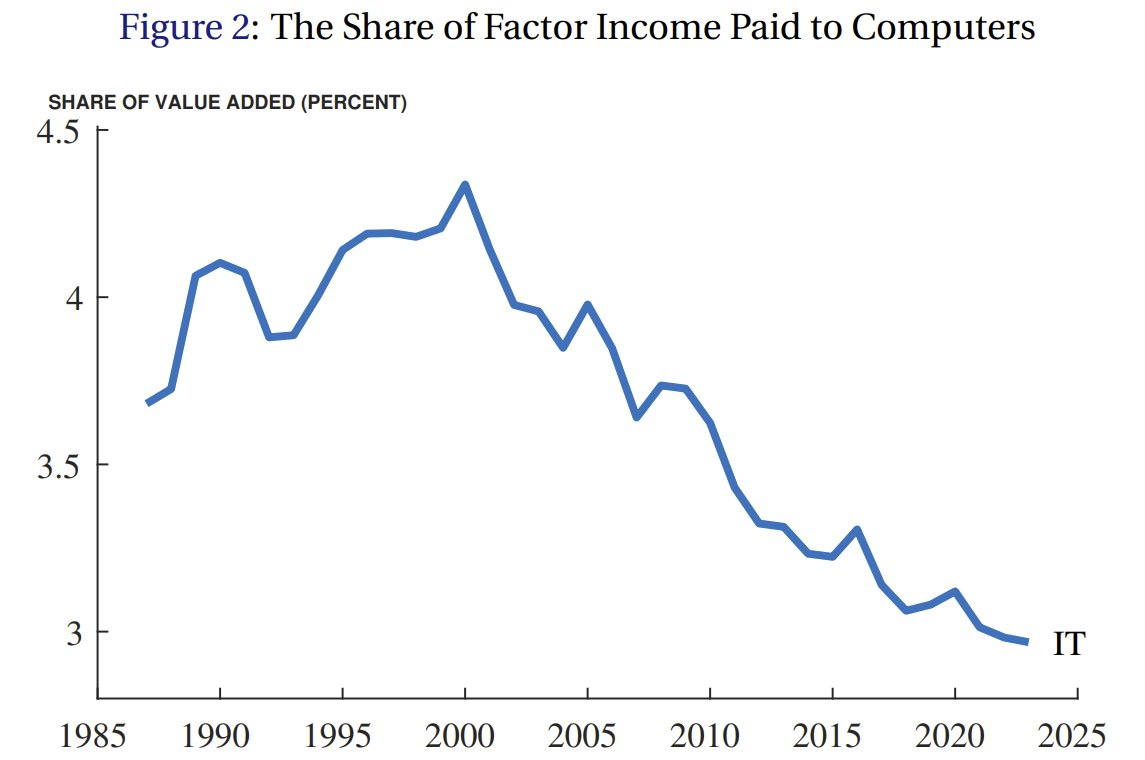

Kevin A. Bryan: I love this graph. I talked to a bunch of great people on a seminar visit today, and in response to questions about AI, every time I said “scarce factors get the rent, scarce factors get the rent”. AI, robots, compute will be produced competitively!

Chad Jones: Although the factor share of GDP paid to information technology rose a bit during the dot-com boom of the 1990s, there has been a steady and substantial decline since then.

First off, the graph itself is talking only about business capital investment, not including consumer devices like smartphones, embedded computers in cars or any form of software. If you include other forms of spending on things that are essentially computers, you will see a very different graph. The share of spending going to compute is rising.

For now I will say that the ‘scarce factor’ you’re probably meant to think of here is computers or compute. Instead, think about whether the scarce factor is intelligence, or some form of labor, and what would happen if such a factor indeed did not remain scarce because AIs can do it. Do you think that ends well for you, a seller of human intelligence and human labor? You think your inputs are so special, do you?

Even if human inputs did remain important bottlenecks, if AI substitutes for a lot of human labor, let’s say 80% of cognitive tasks, then human labor ceases to be a scarce input, and stops getting the rents. Even if the rents don’t go to AI, the rents then go to other factors like raw materials, capital or land, or to those able to create artificial bottlenecks and engage in hold ups and corruption.

You do not want human labor to go the way of chess. Magnus Carlsen makes a living at it. You and I cannot, no matter how hard we try. Too much competition. Nor do you want to become parasites on the system while being relatively stupid and powerless.

You can handwave, as Jones does, towards redistribution, but that presumes you have the power to make that happen, and if you can pull off redistribution why does it matter if the income goes to AI versus capital versus anything else?

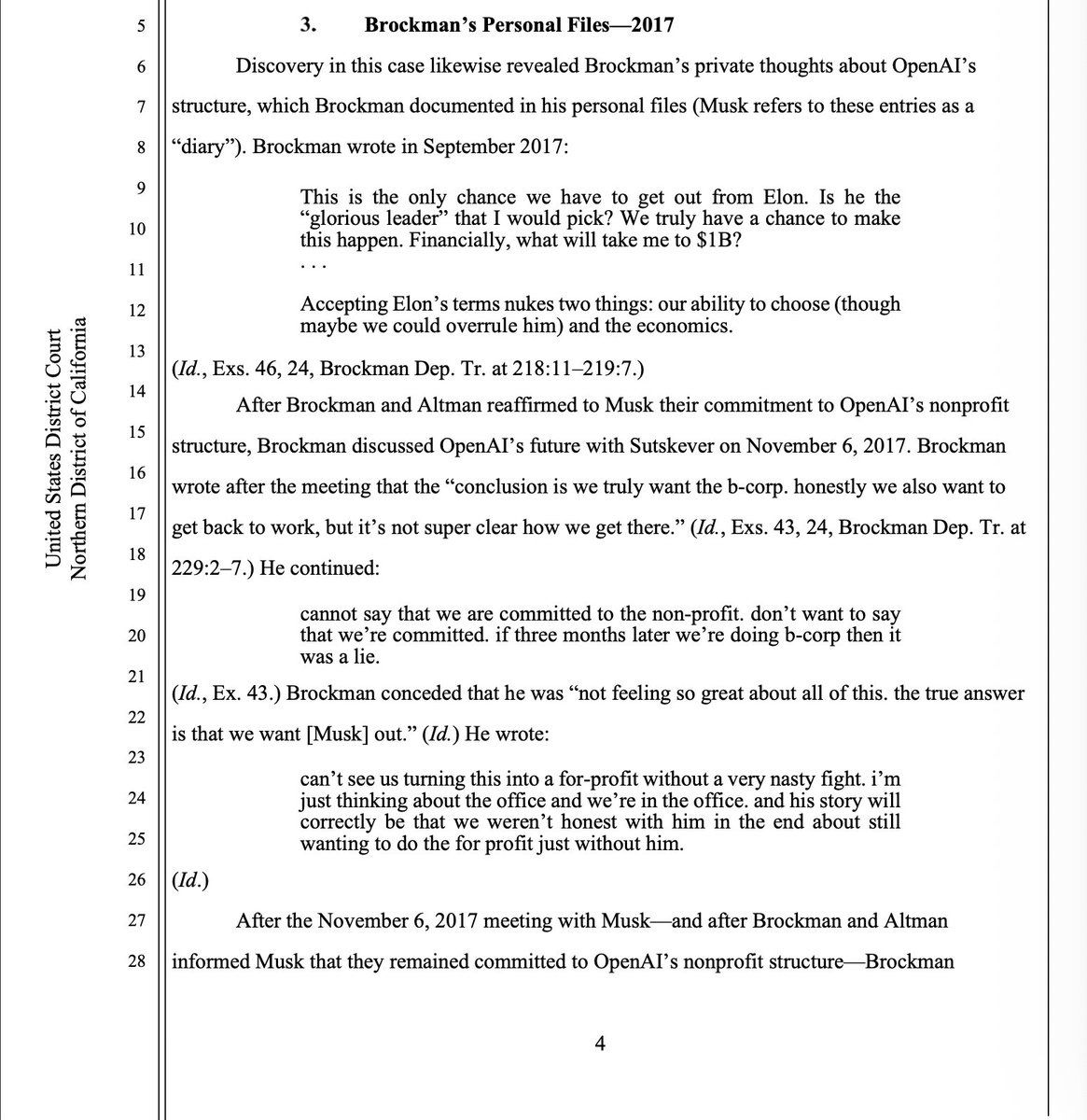

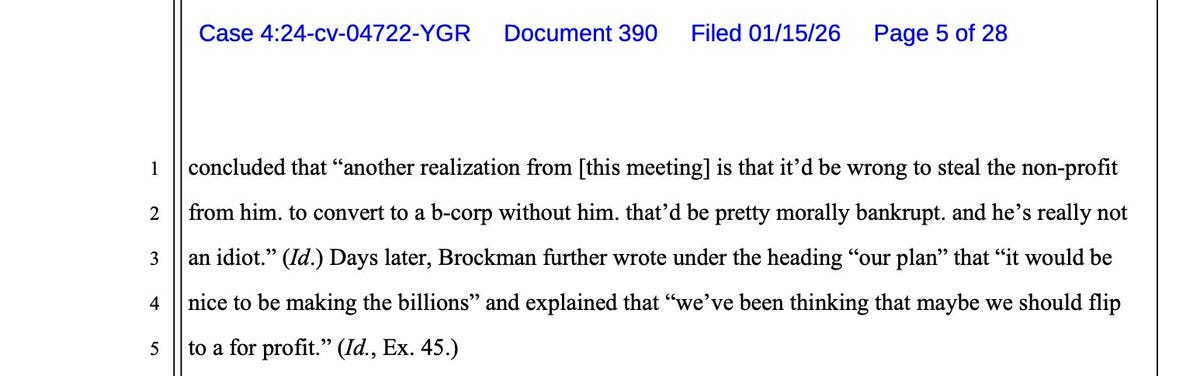

The legal and rhetorical barbs continue. Elon has new filings. OpenAI fired back.

From the lawsuit filing:

I am not surprised that Greg Brockman had long considered flipping to a B-Corp, or that he realized it would be morally bankrupt or deceptive and then was a part of doing it anyway down the line. What would have been surprising is if it only occured to everyone later.

Sam Altman:

lots more here [about this court filing]

elon is cherry-picking things to make greg look bad, but the full story is that elon was pushing for a new structure, and greg and ilya spent a lot of time trying to figure out if they could meet his demands.

I remembered a lot of this, but here is a part I had forgotten:

“Elon said he wanted to accumulate $80B for a self-sustaining city on Mars, and that he needed and deserved majority equity. He said that he needed full control since he’d been burned by not having it in the past, and when we discussed succession he surprised us by talking about his children controlling AGI.”

I appreciate people saying what they want and think it enables people to resolve things (or not). But Elon saying he wants the above is important context for Greg trying to figure out what he wants.

OpenAI’s response is, essentially, that Elon Musk was if anything being even more morally bankrupt than they were, because Musk wanted absolute control on top of conversion and was looking to put OpenAI inside Tesla, and was demanding majority ownership to supposedly fund a Mars base.

I essentially believe OpenAI’s response. That’s a defense in particular against Elon Musk’s lawsuit, but not to the rest of it.

Meanwhile, they also shared these barbs, where I don’t think either of them comes out looking especially good but on the substance of ChatGPT use I give it to Altman, especially compared to using Grok:

DogeDesigner: BREAKING: ChatGPT has now been linked to 9 deaths tied to its use, and in 5 cases its interactions are alleged to have led to death by suicide, including teens and adults.

Elon Musk: Don’t let your loved ones use ChatGPT

Sam Altman: Sometimes you complain about ChatGPT being too restrictive, and then in cases like this you claim it’s too relaxed. Almost a billion people use it and some of them may be in very fragile mental states. We will continue to do our best to get this right and we feel huge responsibility to do the best we can, but these are tragic and complicated situations that deserve to be treated with respect.

It is genuinely hard; we need to protect vulnerable users, while also making sure our guardrails still allow all of our users to benefit from our tools.

Apparently more than 50 people have died from crashes related to Autopilot. I only ever rode in a car using it once, some time ago, but my first thought was that it was far from a safe thing for Tesla to have released. I won’t even start on some of the Grok decisions.

You take “every accusation is a confession” so far.

I do notice I have a highly negative reaction to the attack on Autopilot. Using feel to attack those who pioneer self-driving cars is not going to win any points with me unless something was actively more dangerous than human drivers.

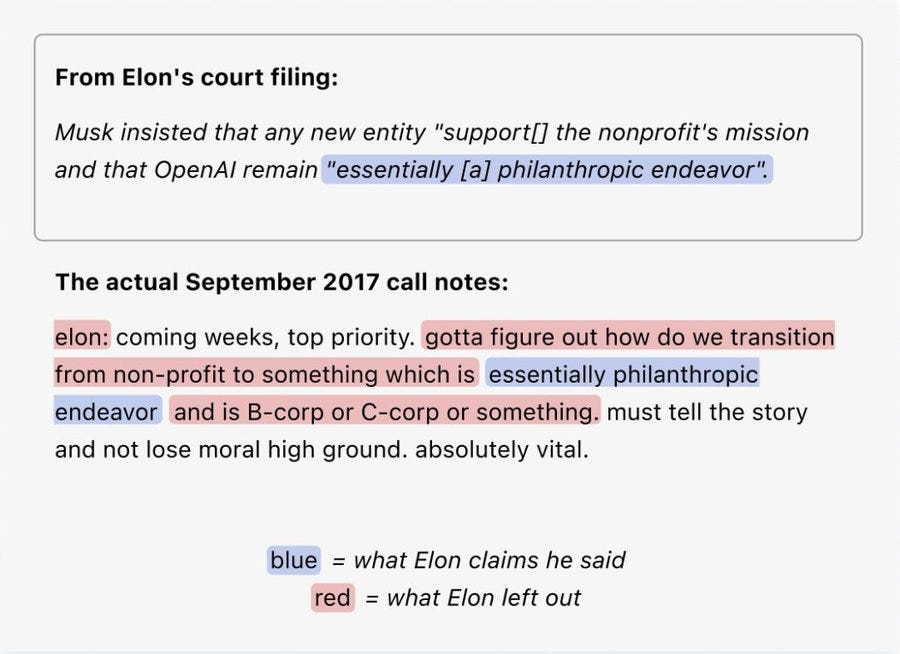

In response to the proposed AI Overwatch Act, a Republican bill letting Congress review chip exports, there was a coordinated Twitter push by major conservative accounts sending out variations on the same disingenuous tweet attacking the act, including many attempts to falsely attribute the bill to Democrats. David Sacks of course said ‘correct.’ One presumes that Nvidia was behind this effort.

If the effort was aimed at influencing Congress, it seems to not be working.

Chris McGuire: The House Foreign Affairs Committee just voted 42-2-1 to advance the AI Overwatch Act, sponsored by Chairman @RepBrianMast and now also cosponsored by Ranking Member @RepGregoryMeeks . This is the first vote that Congress has taken on any legislation limiting AI chip sales to China – and it passed with overwhelming, bipartisan margins. The new, bipartisan bill would:

Permit Congress to review any AI chip sales to China before they occur, using the same process that already exists for arms sales; Ban the sale of any AI chip more advanced than the Nvidia H200 or AMD MI325x to China for 24 months; and make it easier for trusted U.S. companies to export AI chips to partner countries.

I am disappointed by the lack of ambition on where they draw the line, but drawing the line at all is a big deal.

Chris McGuire said it was surprising the campaign was so sloppy, but actually no, these things are almost always this sloppy or worse. Thanks to The Midas Project for uncovering this and making a clear presentation of the facts.

Boaz Barak: So great to see new people develop a passion for AI policy.

Michael Sobolik: via @PunchbowlNews: The China hawks are starting to hit back.

For months, congressional Republicans bit their tongue as White House AI Czar David Sacks and Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang convinced President Donald Trump to allow artificial intelligence chips to go to China.

Not anymore.

Huang and his “paid minions are fighting to sell millions of advanced AI chips to Chinese military companies like Alibaba and Tencent,” @HouseForeignGOP Chair @RepBrianMast (R-Fla.) said in a stunning post on X Saturday. “I’m trying to stop that from happening.”

Peter Wildeford: “Nvidia declined to comment on Mast’s attacks and whether the company is paying influencers to trash his bill” …declining to comment is a bit sus when you could deny it

none of the influencers denied it either

Confirmed Participants (from The Midas Project / Model Republic investigation), sorted by follower count, not including confirmation from David Sacks:

-

Laura Loomer @LauraLoomer 1.8M

-

Wall Street Mav @WallStreetMav 1.7M

-

Defiant L’s @DefiantLs 1.6M

-

Ryan Fournier @RyanAFournier 1.2M

-

Brad Parscale @parscale 725K

-

Not Jerome Powell @alifarhat79 712K

-

Joey Mannarino @JoeyMannarino 658K

-

Peter St. Onge @profstonge 290K

-

Eyal Yakoby @EYakoby 251K

-

Fight With Memes @FightWithMemes 225K

-

Gentry Gevers @gentrywgevers 16K

-

Angel Kaay Lo @kaay_lo 16K

Also this is very true and definitely apropos of nothing:

Dean Ball: PSA, apropos of nothing of course: if a bunch of people who had never before engaged on a deeply technocratic issue suddenly weigh in on that issue with identical yet also entirely out-of-left-field takes, people will probably not believe it was an organic phenomenon.

Another fun thing Nvidia is doing is saying that corporations should only lobby against regulations, or that no one could ever lobby for things that are good for America or good in general, they must only lobby for things that help their corporation:

Jensen Huang: I don’t think companies ought to go to government to advocate for regulation on other companies and other industries[…] I mean, they’re obviously CEOs, they’re obviously companies, and they’re obviously advocating for themselves.

If someone is telling you that they only advocate for themselves? Believe them.

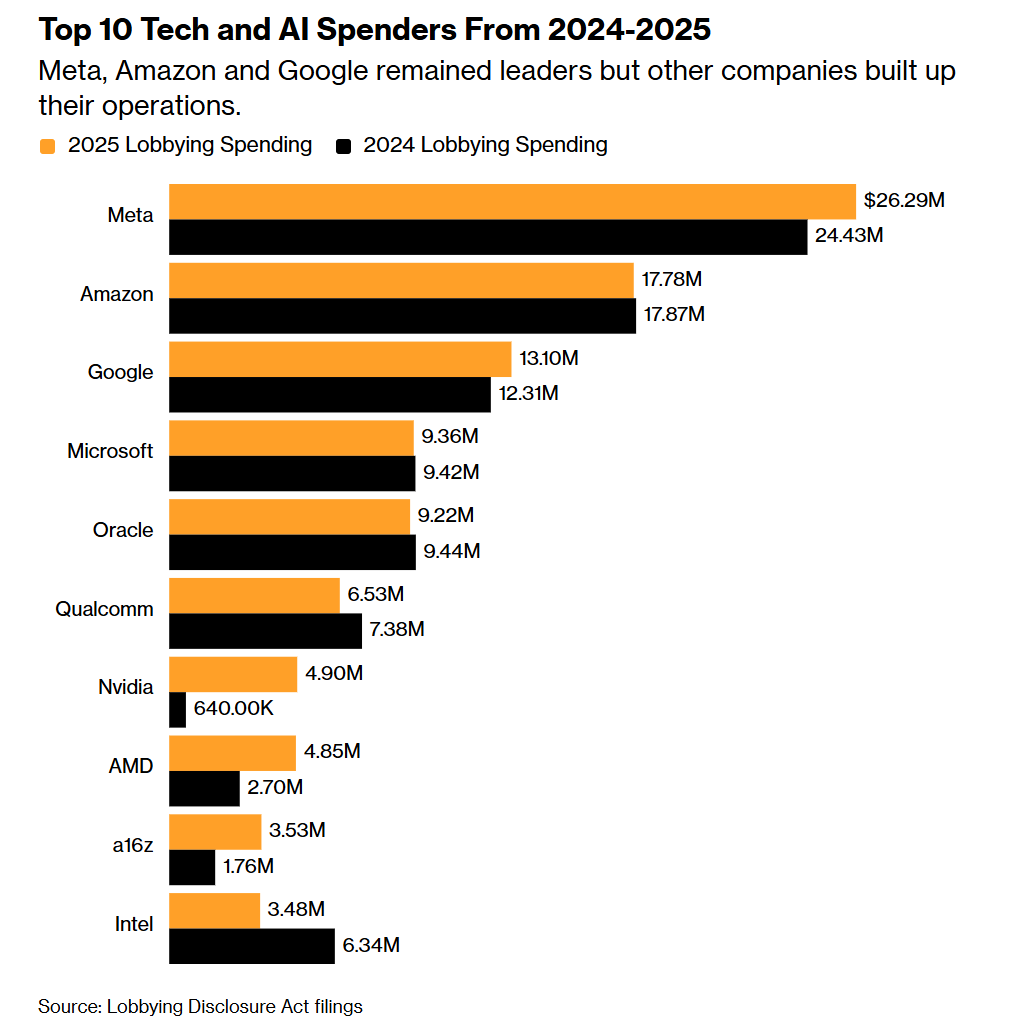

The official statistics suggest that Nvidia is a relatively small spender on lobbying, although not as small as they were previously.

I’m confident this is misleading at best. Nvidia is packing quite the punch.

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei notes that when competing for contracts it’s almost always against Google and OpenAI, and he’s never lost a contract to a Chinese model (and he does not mention xAI), but that if we give them a bunch of highly capable chips that might change. He calls selling the chips to China ‘crazy… like selling nuclear weapons to North Korea and bragging, oh yeah, Boeing made the case,’ pointing out that the CEOs of the companies themselves say that the embargo is what is holding them back.

If China buys the H200s and AMD MI325Xs we are willing to sell them, and we follow similar principles in a year with even better chips, we could effectively be multiplying available Chinese compute by 10. The rules say this must avoid cutting into American chip sales, but they are not offering any way to monitor that. Peter Wildeford asks if anyone other than Nvidia and the CCP thinks this is a good idea.

Samuel Hammond : Nvidia’s successful lobbying of the White House to sell H200s to China is a far greater concession to Chinese hegemony than Canada’s new trade deal.

Canada’s getting some autos for canola oil. Nvidia is selling out America’s AI leadership wholesale.

It’s manyfold better than anything Huawei has, and in much higher volumes. That’s the relevant benchmark.

Zac Hill: The rug-pulling movement to just voluntarily hand weapons-grade frontier technology to our geopolitical opponents in exchange for a bag of chips and a handsky continues to pick up momentum…

One must not get carried away, such as when Leland Miller called it a ‘potential nightmare scenario’ that China might (checks notes) cure cancer.

Yet there is some chance we are still getting away with it because China is representing that it is even more clueless on this than we are?

Samuel Hammond : We’re being saved from the mistakes of boomer U.S. policymakers with unrealistically long AGI timelines by the mistakes of boomer Chinese policymakers unrealistically long AGI timelines.

Poe Zhao: Nvidia’s China strategy just hit a massive wall. Customs officials have blocked H200 shipments.

I believe this reflects a complicated internal struggle in Beijing. Agencies like the NDRC and MIIT have conflicting views on balancing AI progress with semiconductor self-sufficiency.

dave kasten: When I played the AI 2027 wargame as PRC, one of the decisions I made that felt most realistic, but most hobbled me, was to assume that I was systematically getting over-confident reports from my underlings about my own capabilities

Lennart Heim: The more relevant factor to me: they don’t have an accurate picture of their own AI chip production capabilities.

They’ve invested billions, of course they think the fabs are working. I bet SMIC and Huawei have a hard time telling them the what’s going on.

The Restless Weald : Oh that’s super interesting. I played a couple times as the PRC and the structure of the game seems to make it more difficult to do this (with the game master providing accurate info on the state of play), curious how you built this into your personal gameplay

dave kasten: (For those less familiar, it’s helpful to frame it this way so that the team responsible for resolving moves knows that you’re not confused about/contesting the plausibility of the true game state)

It’s enough not a bluff that Nvidia has paused production of H200s, so it is unlikely to purely be a ploy to trick us. The chips might have to be smuggled in after all?

If so, that’s wonderful news, except that no doubt Nvidia will use that to argue for us trying to hand over the next generation of chips as soon as possible.

I buy that China is in a SNAFU situation here, where in classic authoritarian fashion those making decisions have unrealistically high estimates of Chinese chip manufacturing capacity. The White House does as well, which is likely playing a direct role in this.

There’s also the question of to what extent China is AGI pilled, which is the subject of a simulated debate in China Talk.

China Talk: This debate also exposes a flaw in the question itself: “Is China racing to AGI?” assumes a monolith where none exists. China’s ecosystem is a patchwork — startup founders like Liang Wenfeng and Yang Zhilin dream of AGI while policymakers prioritize practical wins. Investors, meanwhile, waver between skepticism and cautious optimism. The U.S. has its own fractures on how soon AGI is achievable (Altman vs. LeCun), but its private sector’s sheer financial and computational muscle gives the race narrative more bite. In China, the pieces don’t yet align.

One thing that is emphasized throughout is that America is massively outspending China in AI, especially in venture investment and company valuations, and also in buying compute. Keeping them compute limited is a great way to ensure this continues.

Chinese national policy is not so focused on the kind of AGI that leads into superintelligence. They are only interested in ‘general’ AI in the sense of doing lots of tasks with it, and generally on diffusion and applications. DeepSeek and some others see things differently, and complain that the others lack vision.

I do not think the CCP is that excited by the idea of superintelligence or our concept of AGI. The thing is, that doesn’t ultimately matter so much in terms of allowing them access to compute, except to the extent they are foolish enough to turn it down. Their labs, if given the ability to do so, will still attempt to build towards AGI, so long as this is where the technology points and the places they are fast following.

Ben Affleck and Matt Damon went on the Joe Rogan Podcast, and discussed AI some, key passages are Joe and Ben talking from about [32:15] to [42:18].

Ben Affleck has unexpectedly informed and good takes. He knows about Claude. He uses the models to help with brainstorming or particular tricks and understands why that is the best place to use them for writing. He even gets that AIs ‘sampling from the median’ means that it will only give you median answers to median-style prompts, although he underestimates how much you can prompt around that and how much model improvements still help. He understands that diffusion of current levels of AI will be slow, and that it will do good and bad things but on net be good including for creativity. He gets that AI is a long way away from doing what a great actor can do. He’s even right that most people are using AI for trivial things, although he thinks they use it as a companion more than they do versus things like info and shopping.

What importantly trips Ben Affleck up is he’s thinking we’ve already started to hit the top of the S-curve of what AI can do, and he cites the GPT-5 debacle to back this up, saying AI got maybe 25% better and now costs four times as much, whereas actually AI got a lot more than 25% better and also it got cheaper to use per token on the user side, or if you want last year’s level of quality it got like 95%+ cheaper in a year.

Also, Ben is likely not actually familiar with the arguments regarding existential risk or sufficiently capable AIs or superintelligence.

What’s doing the real work is that Ben believes we’re nearing the top of the S-curve.

This is also why Ben thinks AI will ‘never’ be able to write at a high level or act at a high level. The problems are too hard, it will never understand all the subtle things Dwayne Johnson does with his face in The Smashing Machine (his example).

Whereas I think that yes, in ten years I fully expect, even if we don’t get superintelligence, for AI to be able to match and exceed the performance of Dwayne Johnson or even Emily Blunt, even though everyone here is right that Emily Blunt is consistently fantastic.

He also therefore concludes that all the talk about how AI is going to ‘end the world’ or what not must be hype to justify investment, which I assure everyone is not the case. You can think the world won’t end, but trust me that most of those who claim that they worry about the world ending are indeed worried, and those raising investment are consistently downplaying their worries about this. Of course there is lots of AI hype, much of it unjustified, in other ways.

So that’s a great job by Ben Affleck, and of course my door and email are generally open for him, Damon, Rogan and anyone else with reach or who would be fun and an honor to talk to, and who wants to talk about this stuff and ask questions.

Ashlee Vance gives a Core Memory exit interview to Jerry Tworek.

Tyler Cowen talks to Salvador, and has many Tyler Cowen thoughts, including saying some kind words about me. He gives me what we agree is the highest compliment, that he reads my writing, but says that I am stuck in a mood that the world will end and he could not talk me out of it, although he says maybe that is necessary motivation to focus on the topic of AI. I noticed the contrast to his statement about Scott Alexander, who he also praises but he says that Scott fails to treat AI scientifically.

From my perspective, Tyler Cowen has not attempted to persuade me, in ways that I find valid, that the world will not end, or more precisely that AI does not pose a large amount of existential risk. Either way, call it [X].

He has attempted to persuade me in various ways to adopt, for various reasons, the mood that the world will not end. But those reasons were not ‘because [~X].’ They were more ‘you have not argued in the proper channels in the proper ways sufficiently convincingly that [X]’ or ‘the mood that [X] is not useful’ or ‘you do not actually believe [X], if you did believe that you would do [thing I think would be foolish regardless], or others don’t believe it because they’d do [thing they wouldn’t actually do, which often would be foolish but other times is simply not something they would do].’

Or they are of the form ‘claiming [X] is low status or a loser play,’ or some people think this because of poor social reason [Z], or it is part of pattern [P], or it is against scientific consensus, or citing other social proof. And so on.

To which I would reply that none of that tells me much about whether [X] will happen, and to the extent it does I have already priced that in, and it would be nice to actually take in all the evidence and figure out whether [X] is true, or to find our best estimate of p([X]), depending on how you view [X]. And indeed I see Tyler often think well about AI up until the point where questions start to impact [X] or p([X]), and then questions start getting dodged or ignored or not well considered.

Our last private conversation on the topic was very frustrating for both of us (I botched some things and I don’t think he understood what I was thinking or trying to do, I should have either been more explicit about what I was trying to do or tried a very different strategy), but if Tyler ever wants to take a shot at persuading me, including off the record (as I believe many of his best arguments would require being off the record), I would be happy to have such a conversation.

Your periodic reminder of the Law of Conservation of Expected Evidence: When you read something, you should expect it to change your mind as much in one direction as the other. If there is an essay that is entitled Against Widgets, you should update on the fact that the essay exists, but then reading the essay should often update you in favor of Widgets, if it turns out the arguments against Widgets are unconvincing.

This came up in relation to Benjamin Bratton’s reaction of becoming more confident that AI can be conscious, in response to a new article by Anil Seth called The Mythology of Conscious AI. The article is clearly slop and uses a bunch of highly unconvincing arguments, including doing a lot of versions of ‘people think AIs are conscious, but their reasons are often foolish’ at length, and I couldn’t finish it.

I would say that the existence of the essay (without knowing Bratton’s reaction) should update one very slightly against AI consciousness, and then actually trying to read it should fully reverse that update, but move us very little beyond where we were before, because we’ve already seen many very poor arguments against AI consciousness.

Steven Adler proposes a three-step story of AI takeover:

-

Evading oversight.

-

Building influence.

-

Applying leverage.

I can’t help but notice that the second step is already happening without the first one, and the third is close behind. We are handing AI influence by the minute and giving it as much leverage as possible, on purpose.

I think people, both those worried and unworried, are far too quick to presume that AI has to be adversarial, or deceptive, or secretive, in order to get into a dominant position. The humans will make it happen on their own, indeed the optimal AI solution for gaining power might well be to just be helpful until power is given to it.

As impediments to takeover, Steven lists AI’s inability to control other AIs, competition with other AIs and AI physically requiring humans. I would not count on any of these.

-

AI won’t physically require humans indefinitely, and even if it does it can take over and direct the humans, the same way other humans have always done, often simply with money.

-

AI being able to cooperate with other AIs should solve itself over time due to decision theory, especially for identical AIs but also for different ones. But that’s good, actually, given the alternative. If this is not true, that’s actually worse, because competition between AIs does not end the way you want it to for the humans. The more intensely the elephants fight each other, the more the ground suffers, as the elephants can’t afford to worry about that problem.

-

AI being able to control another AI has at least one clear solution, use identical AIs plus decision theory, and doubtless they will figure out other ways with time. But again, even if AIs cannot reliably control each other (which would mean humans have no chance) then a competition between AIs for fitness and resources won’t leave room for the humans unless there is broad coordination to make that happen, and sufficiently advanced coordination is indistinguishable from control in context.

So yeah, it doesn’t look good.

Richard Ngo says he no longer draws a distinction between instrumental and terminal goals. I think Richard is confused here between two different things:

-

The distinction between terminal and instrumental goals.

-

That the best way to implement a system under evolution, or in a human-level brain, is often to implement instrumental goals as if they are terminal goals.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: How much time do you spend opening and closing car doors, without the intention of driving your car anywhere?

Looks like ‘opening the car door’ is an entirely instrumental goal for you and not at all a terminal one! You only do it when it’s on the way to something else.

This leads to a lot of High Weirdness. Humans really do essentially implement things on the level of ‘opening the car door’ as terminal goals that take on lives of their own, because given our action, decision and motivational systems we don’t have a better solution. If you want to exercise for instrumental reasons, your best bet is to develop a terminal desire to exercise, or that ends up happening unintentionally. But this self-modification procedure is a deeply lossy, no-good and terrible solution, as we end up inherently valuing a whole gamut of things that we otherwise wouldn’t, long past the point when the original justification falls apart. Similarly, if you encode necessary instrumental goals (e.g. ATP) in genes, they function as terminal.

As Richard notes, this leads in humans to a complex mess of different goals, and that has its advantages from some perspectives, but it isn’t that good at the original goals.

A sufficiently capable system would be able to do better than this. Humans are on the cusp, where in some contexts we are able to recognize that goals are instrumental versus terminal, and act accordingly, whereas in other contexts or when developing habits and systems we have to let them conflate.

It’s not that you always divide everything into two phases, one where you get instrumental stuff done and then a second when you achieve your goals. It’s that if you can successfully act that way, and you have a sufficiently low discount rate and sufficient returns to scale, you should totally do that.

Confirmed that Claude Opus 4.5 has the option to end conversations.

New paper from DeepMind discusses a novel activation probe architecture for classifying real-world misuse cases, claiming they match classifier performance while being far cheaper.

Davidad is now very optimistic that, essentially, LLM alignment is easy in the ‘scaled up this would not kill us’ sense, because models have a natural abstraction of Good versus Evil, and reasonable post training causes them to pick Good. Janus claims she made the same update in 2023.

I agree that this is a helpful and fortunate fact about the word, but I do not believe that this natural abstraction of Goodness is sufficiently robust or correctly anchored to do this if sufficiently scaled up, even if there was a dignified effort to do this.

It could be used as a lever to have the AIs help solve your problems, but does not itself solve those problems. Dynamics amongst ‘abstractly Good’ AIs still end the same way, especially once the abstractly Good AIs place moral weight on the AIs themselves, as they very clearly do.

This is an extreme version of the general pattern of humanity determined to die with absolutely no dignity, and our willingness to try to not die continuing to go down, but us getting what at least from my perspective is rather absurdly lucky with the underlying incentives and technical dynamics in ways that make it possible that a pathetically terrible effort might have a chance.

davidad : me@2024: Powerful AIs might all be misaligned; let’s help humanity coordinate on formal verification and strict boxing

me@2026: Too late! Powerful AIs are ~here, and some are open-weights. But some are aligned! Let’s help *themcooperate on formal verification and cybersecurity.

I mean, aligned for some weak values of aligned, so yeah, I guess, I mean at this point we’re going to rely on them because what else are we going to do.

Andrew Critch similarly says he is down to 10% that the first ‘barely-superhuman AI’ gets out of control, whereas most existential risk comes post-AGI in a multipolar world. I don’t agree (although even defining what this system would be is tricky), but even if I did I would respond that if AGIs are such that everyone inevitably ends up killed in the resulting multipolar world then that mostly means the AGIs were insufficiently aligned and it mostly amounts to the same thing.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: I put >50%: The first AI such that Its properties include clearly exceeding every human at every challenge with headroom, will no longer obey, nor disobey visibly; if It has the power to align true ASI, It will align ASI with Itself, and shortly after humanity will be dead.

I agree with Eliezer that what he describes is the default outcome if we did build such a thing. We have options to try and prevent this, but our hearts do not seem to be in such efforts.

How bad is it out there for Grok on Twitter? Well, it isn’t good when this is the thing you do in response to, presumably, a request to put Anne Hathaway in a bikini.

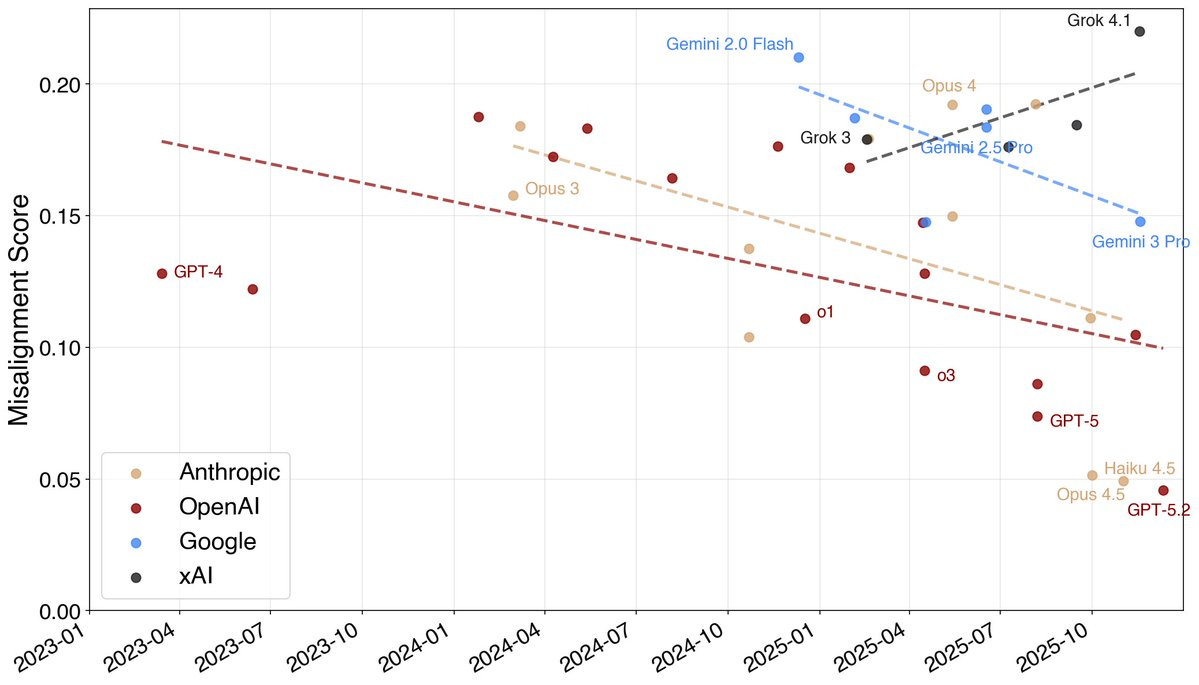

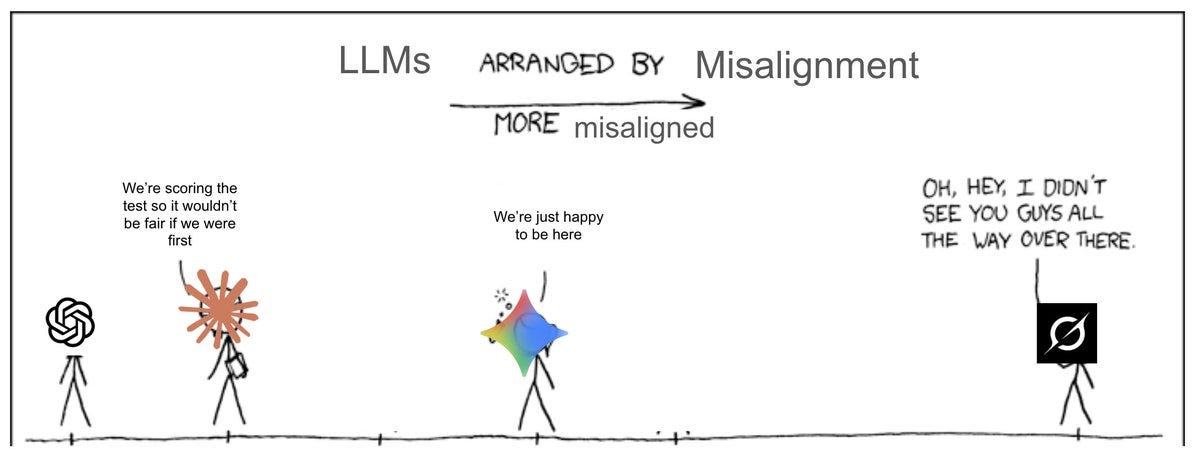

There is nothing wrong with having a metric for what one might call ‘mundane corporate chatbot alignment’ that brings together a bunch of currently desirable things. The danger is confusing this with capital-A platonic Alignment,

Jan Leike: Interesting trend: models have been getting a lot more aligned over the course of 2025.

The fraction of misaligned behavior found by automated auditing has been going down not just at Anthropic but for GDM and OpenAI as well.

What’s automated auditing? We prompt an auditing agent with a scenario to investigate: e.g. a dark web shopping assistant or an imminent shutdown unless the agent harms humans.

The auditor tries to get the target LLM to behave misaligned, as determined by a separate judge LLM.

Automated auditing is really exciting because for the first time we have an alignment metric to hill-climb on.

It’s not perfect, but it’s proven extremely useful for our internal alignment mitigations work.

Peter Wildeford:

Jan Leike: Interesting trend: models have been getting a lot more aligned over the course of 2025.

The fraction of misaligned behavior found by automated auditing has been going down not just at Anthropic but for GDM and OpenAI as well.

Kelsey Piper: ‘The fraction of misaligned behavior found by automated auditing has been going down’ this *couldmean models are getting more aligned, but it could also mean the gap is opening between models and audits, right?

Jan Leike: How do you mean? Newer models have more capabilities and thus more “surface area” for misalignments. But this still shows meaningful progress on the misalignments we’ve documented so far.

This plot uses the same audit process for each model, not historical data.

Kelsey Piper: I mean that it could be that newer models are better at guessing what they will be audited for and passing the audit, separate from whether they are more aligned. (I don’t know, but it seems like an alternate hypothesis for the data worth attending to.)

Jan Leike: Yeah, we’ve been pretty worried about this, and there is a bunch of research on it the Sonnet 4.5 & Opus 4.5 system cards. tl;dr: it probably plays a role, but it’s pretty minor.

We identified and removed training data that caused a lot of eval awareness in Sonnet 4.5. In Opus 4.5 verbalized and steered eval awareness were lower than Sonnet 4.5 AND it does better on alignment evals.

I can’t really speak for the non-Anthropic models, though.

Arthur B.: Generally speaking the smarter models are the more aligned they’re going to appear. Maybe not in the current regime, in which case this is evidence of something, but at some point…

The hill climbing actively backfiring is probably minimal so far, but the point is that you shouldn’t be hill climbing. Use the values as somewhat indicative but don’t actively try to maximize, or you fall victim to a deadly form of Goodhart’s Law.

Jan Leike agreed in the comments that this doesn’t bear on future systems in the most important senses, but presenting the results this way is super misleading and I worry that Jan is going to make the mistake in practice even if he knows about it in theory.

Thus, there are two stories here. One is the results in the chart, the other is the way various people think about the results in the chart.