This post is a roundup of various things related to philanthropy, as you often find in the full monthly roundup.

Peter Thiel warned Elon Musk to ditch donating to The Giving Pledge because Bill Gates will give his wealth away ‘to left-wing nonprofits.’

As John Arnold points out, this seems highly confused. The Giving Pledge is a promise to give away your money, not a promise to let Bill Gates give away your money. The core concern, that your money ends up going to causes one does not believe in (and probably highly inefficiently at that) seems real, once you send money into a foundation ecosystem it by default gets captured by foundation style people.

As he points out, ‘let my children handle it’ is not a great answer, and would be especially poor for Musk given the likely disagreements over values, especially if you don’t actually give those children that much free and clear (and thus, are being relatively uncooperative, so why should they honor your preferences?). There are no easy answers.

A new paper goes Full Hanson with the question Does Maximizing Good Make People Look Bad? They answer yes, if you give deliberately rather than empathetically and seek to maximize impact this is viewed as less moral and you are seen as a less desirable social partner, and donors estimate this effect roughly correctly. Which makes sense if you consider that one advantage of being a social partner is that you can direct your partners with social and emotional appeals, and thereby extract their resources. As with so many other things, you can be someone or do something, and if you focus on one you have to sacrifice some of the other.

This is one place where the core idea of Effective Altruism is pretty great. You create a community of people where it is socially desirable to be deliberative, and scorn is put on those who are empathic instead. If that was all EA did, without trying to drum up more resources or direct how people deliberated? That alone is a big win.

UATX eliminates tuition forever as the result of a $100 million gift from Jeff Yass. Well, hopefully. This gift alone doesn’t fund that, they’re counting on future donations from grateful students, so they might have to back out of this the way Rice had to in 1965. One could ask, given schools like Harvard, Yale and Stanford make such bets and have wildly successful graduates who give lots of money, and still charge tuition, what is the difference?

In general giving to your Alma Mater or another university is highly ineffective altruism. One can plausibly argue that fully paying for everyone’s tuition, with an agreement to that effect, is a lot better than giving to the general university fund, especially if you’re hoping for a cascade effect. It would be a highly positive cultural shift if selective colleges stopped charging tuition. Is that the best use of $100 million? I mean, obviously not even close, but it’s not clear that it is up against the better uses.

Will MacAskill asks what Effective Altruism should do now that AI is making rapid progress and there is a large distinct AI safety movement. He argues EA should embrace the mission of making the transition to a post-AGI society go well.

Will MacAskill: This third way will require a lot of intellectual nimbleness and willingness to change our minds. Post-FTX, much of EA adopted a “PR mentality” that I think has lingered and is counterproductive.

EA is intrinsically controversial because we say things that aren’t popular — and given recent events, we’ll be controversial regardless. This is liberating: we can focus on making arguments we think are true and important, with bravery and honesty, rather than constraining ourselves with excessive caution.

He does not mention until later the obvious objection, which is that the Effective Altruist brand is toxic, to the point that the label is used as a political accusation.

No, this isn’t primarily because EA is ‘inherently controversial’ for the things it advocates. It is primarily because, as I understand things:

-

EA tells those who don’t agree with EA, and who don’t allocate substantial resources to EA causes, that they are bad, and that they should feel bad.

-

EA (long before FTX) adopted in a broad range of ways the ‘PR mentality’ MacAskill rightfully criticizes, and other hostile actions it has taken, also FTX.

-

FTX, which was severely mishandled.

-

Active intentional scapegoating and fear mongering campaigns.

-

Yes, the things it advocates for, and the extent to which it and components of it have pushed for them, but this is one of many elements.

Thus, I think that the things strictly labeled EA should strive to stay away from the areas in which being politically toxic is a problem, and consider the risks of further negative polarization. It also needs to address the core reasons EA got into the ‘PR mentality.’

Here are the causes he thinks this new EA should have in its portfolio (with unequal weight that is not specified):

-

global health & development

-

factory farming

-

AI safety

-

AI character[5]

-

AI welfare / digital minds

-

the economic and political rights of AIs

-

AI-driven persuasion and epistemic disruption

-

AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination

-

the risk of (AI-enabled) human coups

-

democracy preservation

-

gradual disempowerment

-

biorisk

-

space governance

-

s-risks

-

macrostrategy

-

meta

There are some strange flexes in there, but given the historical origins, okay, sure, not bad. Mostly these are good enough to be ‘some of you should do one thing, and some of you should do the other’ depending on one’s preferences and talents. I strongly agree with Will’s emphasis that his shift into AI is an affirmation of the core EA principles worth preserving, of finding the important thing and focusing there.

I am glad to see Will discuss the problem of ‘PR focus.’

By “PR mentality” I mean thinking about communications through the lens of “what is good for EA’s brand?” instead of focusing on questions like “what ideas are true, interesting, important, under-appreciated, and how can we get those ideas out there?

I also appreciate Will’s noticing that the PR focus hasn’t worked even on its own terms, that EA discourse is withering. I would add that EA’s brand and PR position is terrible in large part exactly because EA has often acted, for a long period, in this PR-focused, uncooperative and fundamentally hostile way, that comes across as highly calculated because it was, along with a lack of being straight with people, and eventually people learn the pattern.

This laid the groundwork, when combined with FTX and an intentional series of attacks from a16z and related sources, to poison the well. It wouldn’t have worked otherwise to anything like the same extent.

This was very wise:

And I think this mentality is corrosive to EA’s soul because as soon as you stop being ruthlessly focused on actually figuring out what’s true, then you’ll almost certainly believe the wrong things and focus on the wrong things, and lose out on most impact. Given fat-tailed distributions of impact, getting your focus a bit wrong can mean you do 10x less good than you could have done. Worse, you can easily end up having a negative rather than a positive effect.

Except I think this was a far broader issue than a post-FTX narrow PR focus.

Thus I see ‘PR focus’ as a broader problem than Will does. It is about this kind of communication, but also broader decision making and strategy and prioritization, and was woven into the DNA. It is the asking ‘what maximizes the inputs into EA brands’ question more broadly and centrally involves confusion of costs and benefits. The broader set of things all come from the same underlying mindset.

And I think that mindset greatly predates FTX. Indeed, it is hard to not view the entire FTX incident, and why it went so wrong, as largely about the PR mindset.

As a clear example, he thinks ‘growing the inputs’ was a good focus of EA in the last year. He thinks the focus should now shift to improving the culture, but his justifications still fall into the ‘maximize inputs’ mindset.

In the last year or two, there’s been a lot of focus on growing the inputs. I think this was important, in particular to get back a sense of momentum, and I’m glad that that effort has been pretty successful. I still think that growing EA is extremely valuable, and that some organisation (e.g. Giving What We Can) should focus squarely on growth.

Actively looking to grow the movement has obvious justification, but inputs are costs and not benefits, it is easy to confuse the two, and focus on growing inputs tends to cause severe PR mindset and hostile actions as you strive to capture resources, including people’s time and attention.

Another example I would cite was the response to If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies by the core EA people, including among others Will MacAskill himself and also the head of CEA. This was a very clear example of PR mindset, where quite frankly a decision was made that this was a bad EA look, the moves it proposes were unstrategic, and thus the book should be thrown overboard. If Will is sincere about this reckoning, he should be able to recognize that this is what happened.

What should you do if your brand is widely distrusted and toxic?

The good news, I agree with Will, is that you can stop doing PR.

But this is a liberating fact. It means we don’t need to constrain ourselves with PR mentality — we’ll be controversial whatever we do, so the costs of additional controversy are much lower. Instead, we can just focus on making arguments about things we think are true and important. Think Peter Singer! I also think the “vibe shift” is real, and mitigates much of the potential downsides from controversy.

The bad news is that this doesn’t raise the obvious question, which is why are you doubling down on this toxic brand, especially given the nature of many of the cause areas Will suggests EA enter?

When you hold your conference, This Is The Way:

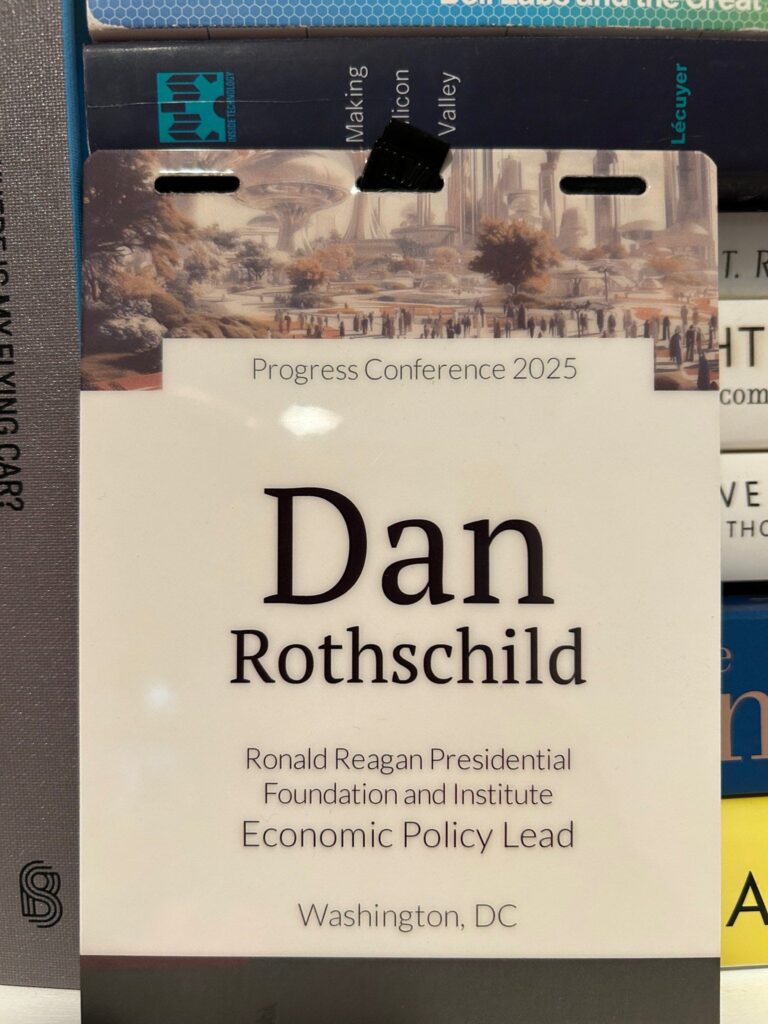

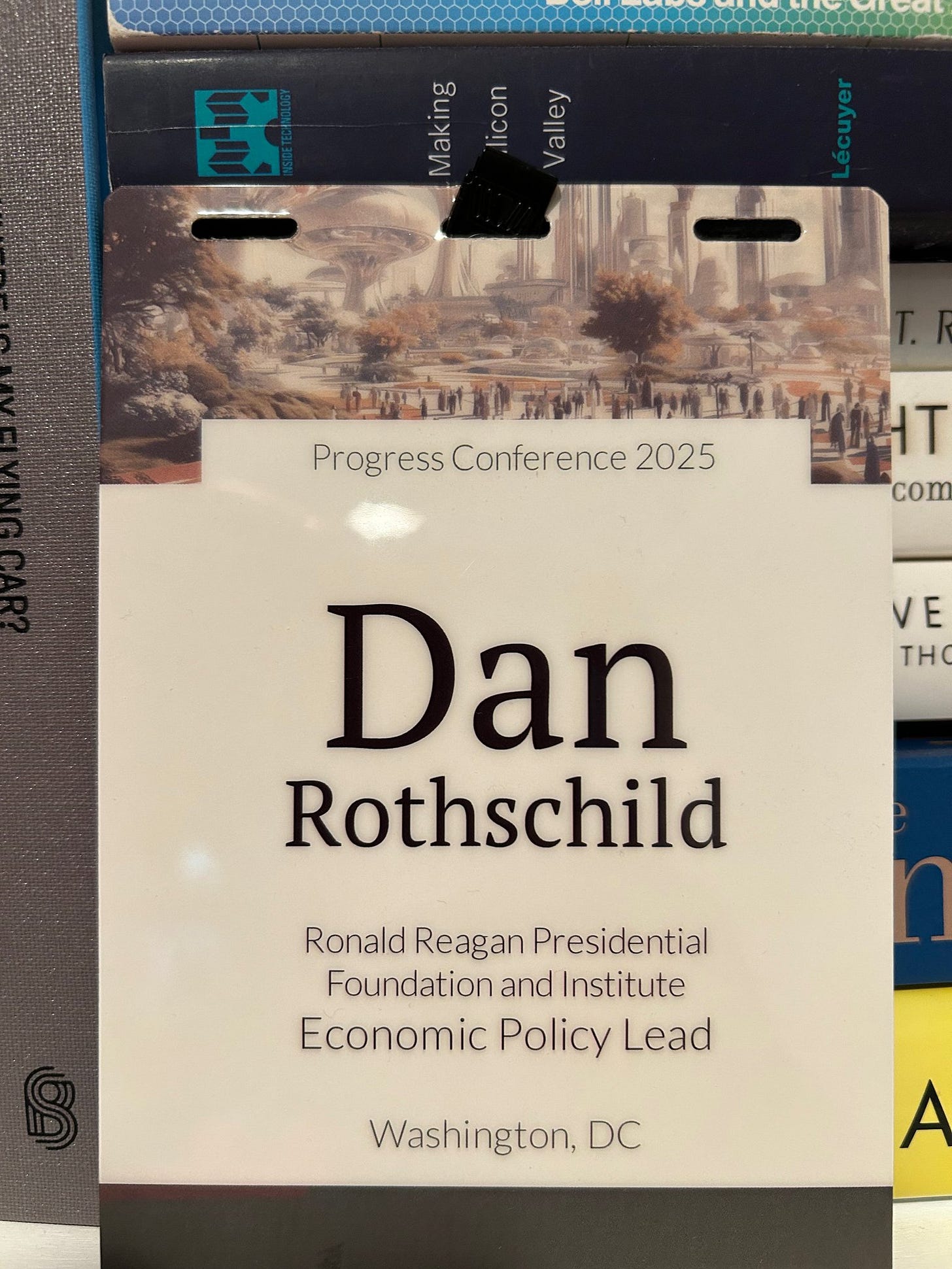

Daniel Rothchild: Many great things about the @rootsofprogress conference this weekend, but I want to take a moment to give a shout out to excellent execution of an oft-overlooked event items that most planners and organizers get wrong: the name badge.

Might this the best conference name tag ever designed? Let’s go through its characteristics.

-

It’s double-sided. That might seem obvious, but a lot of conferences just print on one side. I guess that saves a few cents, but it means half the time the badge is useless.

-

It’s on a lanyard that’s the right length. It came to mid-torso for most people, making it easy to see and catch a glimpse of without looking at people in a weird way.

-

it’s a) attractive and b) not on a safety pin so people actually want to wear it.

-

Most importantly, the most important bit of information–the wearer’s first name–is printed in a maximally large font across the top. You could easily see it from 10 feet away. Again, it might seem obvious… but I go to a lot of events with 14 point printed names.

-

The other information is fine to have in smaller fonts. Job title, organization, location… those are all secondary items. The most important thing is the wearer’s name, and the most important part of that is the first name.

-

After all of the utilitarian questions have been answered… it’s attractive. The color scheme and graphic branding is consistent with the rest of the conference. But I stress, this is the least important part of the badge.

Why does all this matter? Because the best events are those that are designed to facilitate maximal interaction and introduction between people (and to meet IRL people you know online). That’s the case with unconferences, or events with a lot of social/semi-planned time.

There’s basically no reason for everyone not to outright copy this format, forever.

Indeed, one wonders if you shouldn’t have such badges and wear them at parties.

Alex Shintaro Araki offers thoughts on Impact Philanthropy fundraising, and Sarah Constantin confirms this matches her experiences. Impact philanthropy is ideally where you try to make cool new stuff happen, especially a scientific or technological cool new thing, although it can also be simply about ‘impact’ through things like carbon sequestration. This is a potentially highly effective approach, but also a tough road. Individual projects need $20 million to $100 million and most philanthropists are not interested. Sarah notes that many people temperamentally aren’t excited by cool new stuff, which is alien to me, that seems super exciting, but it’s true.

One key insight is that if you’re asking for $3 million you might as well ask for $30 million, provided you have a good pitch on what to do with it, and assuming you pitch people who have the money. If someone is a billionaire, they’re actively excited to be able to place large amounts of money.

Another is that there’s a lot of variance and luck, although he doesn’t call it that. You probably need a deep connection with your funder, but you also need to find your funder at the right time when things line up for them.

Finally, it sounds weird, but it matches my experience that funders need good things to fund even more than founders need to find people to fund them, the same way this is also true in venture capital. They don’t see good opportunities and have limited time. So things like cold emails can actually work.

Expect another philanthropy-related post later this month.