The fun at OpenAI continues.

We finally have the details of how Leopold Aschenbrenner was fired, at least according to Leopold. We have a letter calling for a way for employees to do something if frontier AI labs are endangering safety. And we have continued details and fallout from the issues with non-disparagement agreements and NDAs.

Hopefully we can stop meeting like this for a while.

Due to jury duty and it being largely distinct, this post does not cover the appointment of General Paul Nakasone to the board of directors. I’ll cover that later, probably in the weekly update.

What happened that caused Leopold to leave OpenAI? Given the nature of this topic, I encourage getting the story from Leopold by following along on the transcript of that section of his appearance on the Dwarkesh Patel Podcast or watching the section yourself.

This is especially true on the question of the firing (control-F for ‘Why don’t I’). I will summarize, but much better to use the primary source for claims like this. I would quote, but I’d want to quote entire pages of text, so go read or listen to the whole thing.

Remember that this is only Leopold’s side of the story. We do not know what is missing from his story, or what parts might be inaccurate.

It has however been over a week, and there has been no response from OpenAI.

If Leopold’s statements are true and complete? Well, it doesn’t look good.

The short answer is:

-

Leopold refused to sign the OpenAI letter demanding the board resign.

-

Leopold wrote a memo about what he saw as OpenAI’s terrible cybersecurity.

-

OpenAI did not respond.

-

There was a major cybersecurity incident.

-

Leopold shared the memo with the board.

-

OpenAI admonished him for sharing the memo with the board.

-

OpenAI went on a fishing expedition to find a reason to fire him.

-

OpenAI fired him, citing ‘leaking information’ that did not contain any non-public information, and that was well within OpenAI communication norms.

-

Leopold was explicitly told that without the memo, he wouldn’t have been fired.

You can call it ‘going outside the chain of command.’

You can also call it ‘fired for whistleblowing under false pretenses,’ and treating the board as an enemy who should not be informed about potential problems with cybersecurity, and also retaliation for not being sufficiently loyal to Altman.

Your call.

For comprehension I am moving statements around, but here is the story I believe Leopold is telling, with time stamps.

-

(2: 29: 10) Leopold joined superalignment. The goal of superalignment was to find the successor to RLHF, because it probably won’t scale to superhuman systems, humans can’t evaluate superhuman outputs. He liked Ilya and the team and the ambitious agenda on an important problem.

-

Not probably won’t scale. It won’t scale. I love that Leike was clear on this.

-

(2: 31: 24) What happened to superalignment? OpenAI ‘decided to take things in a somewhat different direction.’ After November there were personnel changes, some amount of ‘reprioritization.’ The 20% compute commitment, a key part of recruiting many people, was broken.

-

If you turn against your safety team because of corporate political fights and thus decide to ‘go in a different direction,’ and that different direction is to not do the safety work? And your safety team quits with no sign you are going to replace them? That seems quite bad.

-

If you recruit a bunch of people based on a very loud public commitment of resources, then you do not commit those resources? That seems quite bad.

-

(2: 32: 25) Why did Leopold leave, they said you were fired, what happened? I encourage reading Leopold’s exact answer and not take my word for this, but the short version is…

-

Leopold wrote a memo warning about the need to secure model weights and algorithmic secrets against espionage, especially by the CCP.

-

After a major security incident, Leopold shared that memo with the board.

-

HR responded by saying that worrying about CCP espionage was racist and unconstructive. “I got an official HR warning for sharing the memo with the board.”

-

In case it needs to be said, it is totally absurd to say this was either racist or unconstructive. Neither claim makes any sense in context.

-

In the interviews before he was fired, Leopold was asked extensively about his views on safety and security, on superalignment’s ‘loyalty’ to the company and his activity during the board events.

-

It sure sounds like OpenAI was interpreting anything but blind loyalty, or any raising of concerns, as damage and a threat and attempting to kill or route around it.

-

When he was fired, Leopold was told “the reason this is a firing and not a warning is because of the security memo.”

-

If Leopold’s statements are true, it sure sounds like he was fired in retaliation for being a whistleblower, that HR admitted this, and it reveals that HR took the position that OpenAI was in a hostile relationship with its own board and had an active policy of hiding mission-critical information from them.

-

I have not seen any denials of these claims.

-

Leopold’s answer including him saying he could have been more diplomatic, acting almost apologetic. Either this is him bending over backwards to be diplomatic about all this, he has suffered trauma, or both.

-

The main official reason was the ‘leak of information,’ in a brainstormed Google docs memo he shared with outside researchers six months prior, whose actual confidential information was redacted before sharing. In particular OpenAI pointed only to a line about ‘planning for AGI in 2027-2028,’ which was the official public mission of the Superalignment team. They claimed Leopold was ‘unforthcoming during the investigation’ because he couldn’t remember who he shared the document with, but it was a literal Google doc, so that information was easy to retrieve. That leaking claim was the outcome of a team going through all of Leopold’s communication. So that was the worst they could find in what was presumably a search for a reason to fire him.

-

If Leopold’s statements are true and complete, then the leaking claim was at best a pretext. It sure sounds like it was pure and utter bullshit.

-

I have not seen any denials of these claims.

-

If this was the worst they could find, this means Leopold was being vastly more responsible than my model of the median employee at an AI lab.

-

Their other claims listed were that Leopold had spoken externally including to a think tank and a DM to a friend about his view that AGI would likely become a government project, and therefore had ‘engaged on policy in a way they didn’t like.’ Such discussions were, Leopold claims, within standard norms at OpenAI, and several dozen former colleagues confirmed this.

-

Again, if true, this sounds like what you get from a highly unsuccessful fishing expedition. There is nothing here.

-

The alternative, that such actions are against the norms of OpenAI and justify firing an employee, are vastly worse. If it is your policy that you fire people for discussing key non-confidential facts about the world and the safety situation with outside colleagues, seriously, what the hell?

-

Oh, and the other thing Leopold did was not sign the employee letter. He says he agreed the board should have resigned but had issues with letter details, in particular that it called for the board to resign but not for the new board to be independent. He notes there was pressure to sign.

-

Again, this sure looks like what it looks like.

-

If you have a letter like this, and a huge portion of those who do not sign are gone six months later, you can draw various conclusions.

-

At best, you can say that those who did not agree with the direction of the company felt unwelcome or that their work was harmful or both, and decided to leave.

-

Another question is, if you see everyone who failed to sign being frozen out and retaliated against, what should you conclude there?

-

The first thing you would conclude is that a lot of employees likely signed the letter in order to protect themselves, so saying that you had ‘95% approval’ becomes meaningless. You simply do not know how many people actually believed what they signed.

-

The second obvious thing is that all of this sounds like retaliation and pressure and other not good things.

-

Leopold was fired right before his cliff, with equity of close to a million dollars. He was offered the equity if he signed the exit documents, but he refused.

-

The timing here does not seem like a coincidence.

-

We are fortunate that Leopold decided freedom was priceless and refused.

-

This is ‘how it is supposed to work’ in the sense that at least Leopold was offered real consideration for signing. It still seems like terrible public policy to have it go that way, especially if (as one might presume from the circumstances) they fired him before the cliff in order to get the leverage.

-

Leopold really should consult a lawyer on all this if he hasn’t done so.

-

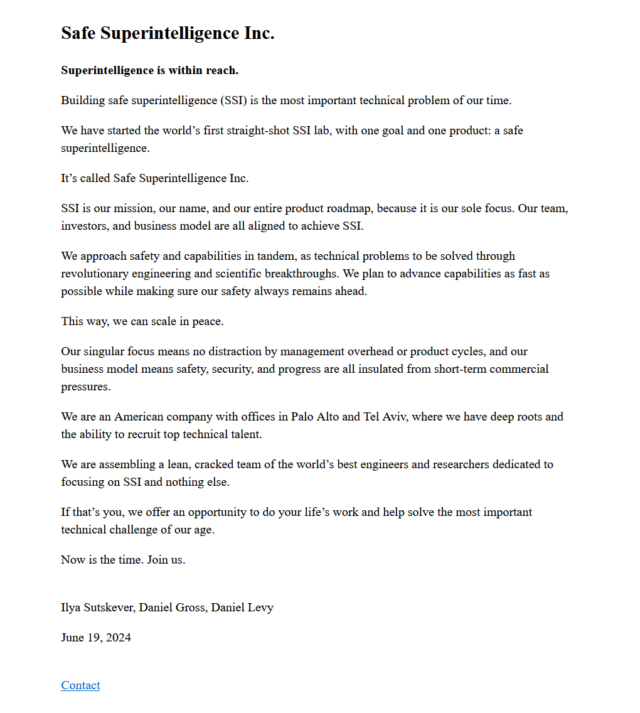

It seems highly plausible that this incident was a major causal factor in the decisions by Jan Leike and Ilya Sutskever to leave OpenAI.

-

(2: 42: 49) Why so much drama? The stakes, and the cognitive dissonance of believing you are building AGI while avoiding grappling with the implications. If you actually appreciated what it meant, you would be thinking long and hard about security and prioritize it. You would care about the geopolitical risks of placing data centers in the UAE. You would take your safety commitments seriously, especially when they were heavily used for recruitment, which Leopold says the compute commitments to superalignment were. Leopold indicates breaking the 20% compute commitment to superalignment was part of a pattern of OpenAI not keeping its commitments.

-

One amazing part of this is that Leopold does not mention alignment or existential risks here, other than the need to invest in long term safety. This is what it is like to view alignment and existential risk as mere engineering problems requiring investment to solve, commit resources to solving them and recruit on that basis, then decide to sacrifice your commitments to ship a slightly better consumer product.

-

This is what is looks like when the stakes are as low as they possibly could be. AGI will be a historically powerful technology usable for both good and bad, even if you think all the talk of existential risk or loss of control is nonsense. There is no denying the immense national security implications, even if you think they ‘top out’ well before what Leopold believes, no matter what else is also at stake that might matter more.

-

There are of course… other factors here. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Here is his full Twitter statement he made once he felt free to speak, aimed at ensuring that others are also free to speak.

Daniel Kokotajlo (June 4): In April, I resigned from OpenAI after losing confidence that the company would behave responsibly in its attempt to build artificial general intelligence — “AI systems that are generally smarter than humans.”

I joined with the hope that we would invest much more in safety research as our systems became more capable, but OpenAI never made this pivot. People started resigning when they realized this. I was not the first or last to do so.

When I left, I was asked to sign paperwork with a nondisparagement clause that would stop me from saying anything critical of the company. It was clear from the paperwork and my communications with OpenAI that I would lose my vested equity in 60 days if I refused to sign.

Some documents and emails visible [in the Vox story].

My wife and I thought hard about it and decided that my freedom to speak up in the future was more important than the equity. I told OpenAI that I could not sign because I did not think the policy was ethical; they accepted my decision, and we parted ways.

The systems that labs like OpenAI are building have the capacity to do enormous good. But if we are not careful, they can be destabilizing in the short term and catastrophic in the long term.

These systems are not ordinary software; they are artificial neural nets that learn from massive amounts of data. There is a rapidly growing scientific literature on interpretability, alignment, and control, but these fields are still in their infancy.

There is a lot we don’t understand about how these systems work and whether they will remain aligned to human interests as they get smarter and possibly surpass human-level intelligence in all arenas.

Meanwhile, there is little to no oversight over this technology. Instead, we rely on the companies building them to self-govern, even as profit motives and excitement about the technology push them to “move fast and break things.”

Silencing researchers and making them afraid of retaliation is dangerous when we are currently some of the only people in a position to warn the public.

I applaud OpenAI for promising to change these policies!

It’s concerning that they engaged in these intimidation tactics for so long and only course-corrected under public pressure. It’s also concerning that leaders who signed off on these policies claim they didn’t know about them.

We owe it to the public, who will bear the brunt of these dangers, to do better than this. Reasonable minds can disagree about whether AGI will happen soon, but it seems foolish to put so few resources into preparing.

Some of us who recently resigned from OpenAI have come together to ask for a broader commitment to transparency from the labs. You can read about it here.

To my former colleagues, I have much love and respect for you, and hope you will continue pushing for transparency from the inside. Feel free to reach out to me if you have any questions or criticisms.

I also noticed this in The New York Times.

Kevin Roose (NYT): Eventually, Mr. Kokotajlo said, he became so worried that, last year, he told Mr. Altman that the company should “pivot to safety” and spend more time and resources guarding against A.I.’s risks rather than charging ahead to improve its models. He said that Mr. Altman had claimed to agree with him, but that nothing much changed.

That is the pattern. Altman will tell you what you want to hear.

It seems worth reproducing the letter in full. I am sure they won’t mind.

We are current and former employees at frontier AI companies, and we believe in the potential of AI technology to deliver unprecedented benefits to humanity.

We also understand the serious risks posed by these technologies. These risks range from the further entrenchment of existing inequalities, to manipulation and misinformation, to the loss of control of autonomous AI systems potentially resulting in human extinction. AI companies themselves have acknowledged these risks [1, 2, 3], as have governments across the world [4, 5, 6] and other AI experts [7, 8, 9].

We are hopeful that these risks can be adequately mitigated with sufficient guidance from the scientific community, policymakers, and the public. However, AI companies have strong financial incentives to avoid effective oversight, and we do not believe bespoke structures of corporate governance are sufficient to change this.

AI companies possess substantial non-public information about the capabilities and limitations of their systems, the adequacy of their protective measures, and the risk levels of different kinds of harm. However, they currently have only weak obligations to share some of this information with governments, and none with civil society. We do not think they can all be relied upon to share it voluntarily.

So long as there is no effective government oversight of these corporations, current and former employees are among the few people who can hold them accountable to the public. Yet broad confidentiality agreements block us from voicing our concerns, except to the very companies that may be failing to address these issues. Ordinary whistleblower protections are insufficient because they focus on illegal activity, whereas many of the risks we are concerned about are not yet regulated. Some of us reasonably fear various forms of retaliation, given the history of such cases across the industry. We are not the first to encounter or speak about these issues.

We therefore call upon advanced AI companies to commit to these principles:

-

That the company will not enter into or enforce any agreement that prohibits “disparagement” or criticism of the company for risk-related concerns, nor retaliate for risk-related criticism by hindering any vested economic benefit;

-

That the company will facilitate a verifiably anonymous process for current and former employees to raise risk-related concerns to the company’s board, to regulators, and to an appropriate independent organization with relevant expertise;

-

That the company will support a culture of open criticism and allow its current and former employees to raise risk-related concerns about its technologies to the public, to the company’s board, to regulators, or to an appropriate independent organization with relevant expertise, so long as trade secrets and other intellectual property interests are appropriately protected;

-

That the company will not retaliate against current and former employees who publicly share risk-related confidential information after other processes have failed. We accept that any effort to report risk-related concerns should avoid releasing confidential information unnecessarily. Therefore, once an adequate process for anonymously raising concerns to the company’s board, to regulators, and to an appropriate independent organization with relevant expertise exists, we accept that concerns should be raised through such a process initially. However, as long as such a process does not exist, current and former employees should retain their freedom to report their concerns to the public.

Signed by (alphabetical order):

Jacob Hilton, formerly OpenAI

Daniel Kokotajlo, formerly OpenAI

Ramana Kumar, formerly Google DeepMind

Neel Nanda, currently Google DeepMind, formerly Anthropic

William Saunders, formerly OpenAI

Carroll Wainwright, formerly OpenAI

Daniel Ziegler, formerly OpenAI

Anonymous, currently OpenAI

Anonymous, currently OpenAI

Anonymous, currently OpenAI

Anonymous, currently OpenAI

Anonymous, formerly OpenAI

Anonymous, formerly OpenAI

Endorsed by (alphabetical order):

Yoshua Bengio

Geoffrey Hinton

Stuart Russell

June 4th, 2024

Tolga Bilge: That they have got 4 current OpenAI employees to sign this statement is remarkable and shows the level of dissent and concern still within the company.

However, it’s worth noting that they signed it anonymously, likely anticipating retaliation if they put their names to it.

Neel Nanda: I signed this appeal for frontier AI companies to guarantee employees a right to warn.

This was NOT because I currently have anything I want to warn about at my current or former employers, or specific critiques of their attitudes towards whistleblowers.

But I believe AGI will be incredibly consequential and, as all labs acknowledge, could pose an existential threat. Any lab seeking to make AGI must prove itself worthy of public trust, and employees having a robust and protected right to whistleblow is a key first step.

I particularly wanted to sign to make clear that this was not just about singling out OpenAI. All frontier AI labs must be held to a higher standard.

It is telling that all current OpenAI members who signed stayed anonymous, and two former ones did too. It does not seem like they are doing well on open criticism. But also note that this is a small percentage of all OpenAI employees and ex-employees.

In practice, this calls for four things.

What would this mean?

-

Revoking any non-disparagement agreements (he says OpenAI promised to do this, but no, it simply said it did not ‘intend to enforce’ them, which is very different).

-

Create an anonymous mechanism for employees and former employees to raise safety concerns to the board, regulators and an independent AI safety agency.

-

Support a ‘culture of open criticism’ about safety.

-

Not to retaliate if employees share confidential information when raising risk-related concerns, if employees first use a created confidential and anonymous process.

The first three should be entirely uncontroversial, although good luck with the third.

The fourth is asking a lot. It is not obviously a good idea.

It is a tough spot. You do not want anyone sharing your confidential information or feeling free to do so. But if there is existential danger, and there is no process or the process has failed, what can be done?

Leopold tried going to the board. We know how that turned out.

In general, there are situations where there are rules that should be broken only in true extremis, and the best procedure we can agree to is that if the stakes are high enough, the right move is to break the rules and if necessary you take the consequences, and others can choose to mitigate that post hoc. When the situation is bad enough, you stand up, you protest, you sacrifice. Or you Do What Must Be Done. Here that would be: A duty to warn, rather than a right to warn. Ideally we would like to do better than that.

Kevin Roose at The New York Times has a write-up of related developments.

OpenAI’s non-response was as you would expect:

Kevin Roose (NYT): A spokeswoman for OpenAI, Lindsey Held, said in a statement: “We’re proud of our track record providing the most capable and safest A.I. systems and believe in our scientific approach to addressing risk. We agree that rigorous debate is crucial given the significance of this technology, and we’ll continue to engage with governments, civil society and other communities around the world.”

A Google spokesman declined to comment.

I like Google’s response better.

The fully general counterargument against safety people saying they would actually doing things to enforce safety is what if that means no one is ever willing to hire them? If you threaten to leak confidential information, how do you expect companies to respond?

Joshua Achiam of OpenAI thus thinks the letter is a mistake, and speaks directly to those who signed it.

Joshua Achiam: I think you are making a serious error with this letter. The spirit of it is sensible, in that most professional fields with risk management practices wind up developing some kind of whistleblower protections, and public discussion of AGI risk is critically important.

But the disclosure of confidential information from frontier labs, however well-intentioned, can be outright dangerous. This letter asks for a policy that would in effect give safety staff carte blanche to make disclosures at will, based on their own judgement.

I think this is obviously crazy.

The letter didn’t have to ask for a policy so arbitrarily broad and underdefined. Something narrowly-scoped around discussions of risk without confidential material would have been perfectly sufficient.

…

And, crucially, this letter disrupts a delicate and important trust equilibrium that exists in the field and among AGI frontier lab staff today.

I don’t know if you have noticed: all of us who care about AGI risk have basically been free to care about it in public, since forever! We have been talking about p(doom) nonstop. We simply won’t shut up about it.

This has been politely sanctioned—AND SUPPORTED BY LAB LEADERS—despite what are frankly many structural forces that do not love this kind of thing! The unofficial-official policy all along has been to permit public hand-wringing and warnings!

Just one red line: don’t break trust! Don’t share confidential info.

I admit, that has been pretty great to the extent it is real. I am not convinced it is true that there is only one red line? What could one say, as an employee of OpenAI, before it would get management or Altman mad at you? I don’t know. I do know that whenever current employees of OpenAI talk in public, they do not act like they can express viewpoints approaching my own on this.

The dilemma is, you need to be able to trust the safety researchers, but also what happens if there actually is a real need to shout from the rooftops? How to reconcile?

Joshua Achiam: Good luck getting product staff to add you to meetings and involve you in sensitive discussions if you hold up a flag that says “I Will Scuttle Your Launch Or Talk Shit About it Later if I Feel Morally Obligated.”

Whistleblower protections should exist. Have to exist in some form. But not like this. I’m just going to spend the morning repeatedly applying desk to forehead. Someday, I dream, the own-goals from smart, virtuous people will stop.

Amanda Askell (Anthropic): I don’t think this has to be true. I’ve been proactively drawn into launch discussions to get my take on ethical concerns. People do this knowing it could scuttle or delay the launch, but they don’t want to launch if there’s a serious concern and they trust me to be reasonable.

Also, Anthropic has an anonymous hotline for employees to report RSP compliance concerns, which I think is a good thing.

[Jacob Hilton also responded.]

So, actually, yes. I do think that it is your job to try to scuttle the launch if you feel a moral obligation to do that! At least in the room. Whether or not you are the safety officer. That is what a moral obligation means. If you think an actively unsafe, potentially existentially unsafe thing is about to happen, and you are in the room where it happens, you try and stop it.

Breaking confidentiality is a higher bar. If it is sufficiently bad that you need to use methods that break the rules and take the consequences, you take the consequences. I take confidentiality very seriously, a lot depends on it. One should only go there with a heavy heart. Almost everyone is far too quick to pull that trigger.

The other dilemma is, I would hope we can all agree that we all need to have a procedure where those with concerns that depend on confidential information can get those concerns to the Reasonable Authority Figures. There needs to be a way to go up or around the chain of command to do that, that gets things taken seriously.

As William Saunders says here in his analysis of the letter, and Daniel Ziegler argues here, the goal of the letter here is to create such a procedure, such that it actually gets used. The companies in question, at least OpenAI, likely will not do that unless there would be consequences for failing to do that. So you need a fallback if they fail. But you need that fallback to not give you carte blanche.

Here Jacob Hilton fully explains how he sees it.

Jacob Hilton: In order for @OpenAI and other AI companies to be held accountable to their own commitments on safety, security, governance and ethics, the public must have confidence that employees will not be retaliated against for speaking out.

Currently, the main way for AI companies to provide assurances to the public is through voluntary public commitments. But there is no good way for the public to tell if the company is actually sticking to these commitments, and no incentive for the company to be transparent.

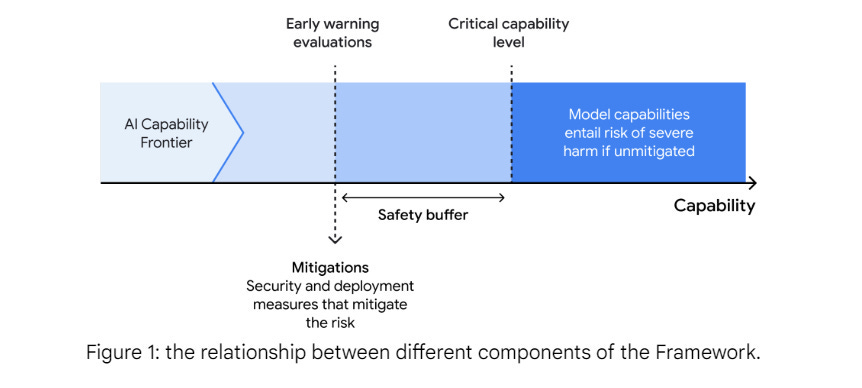

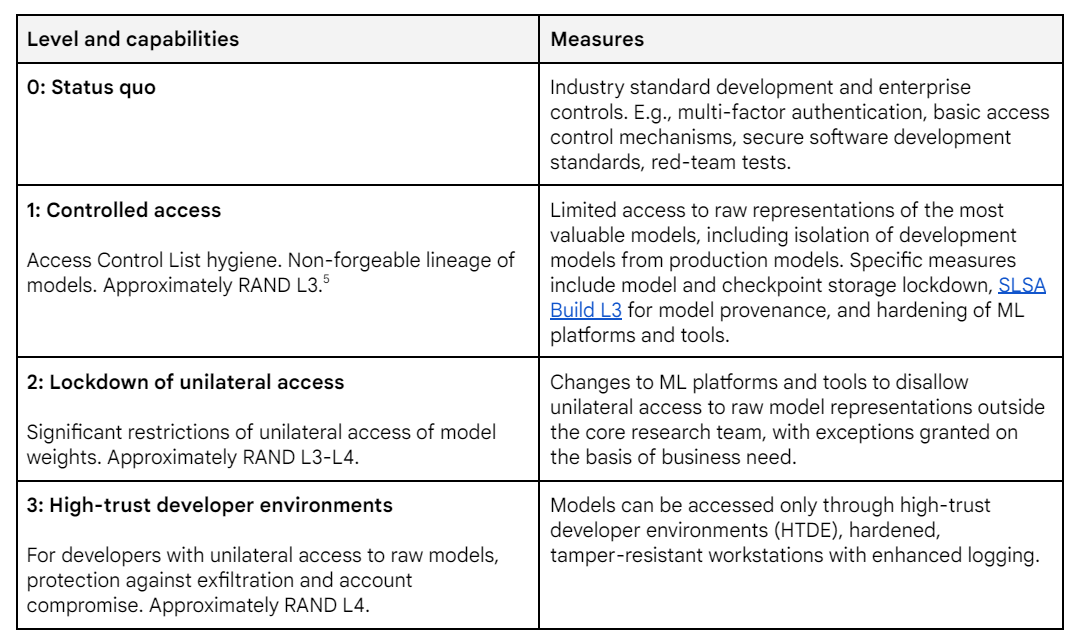

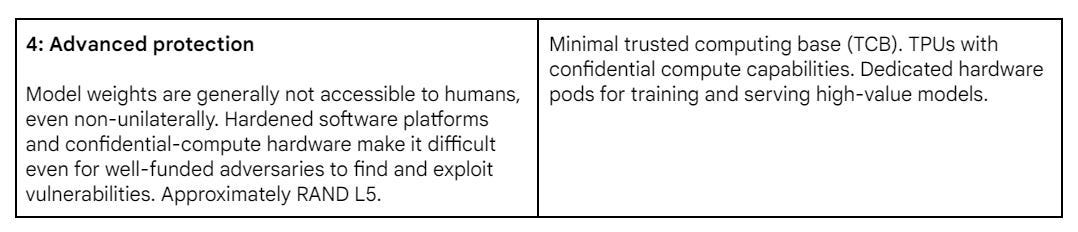

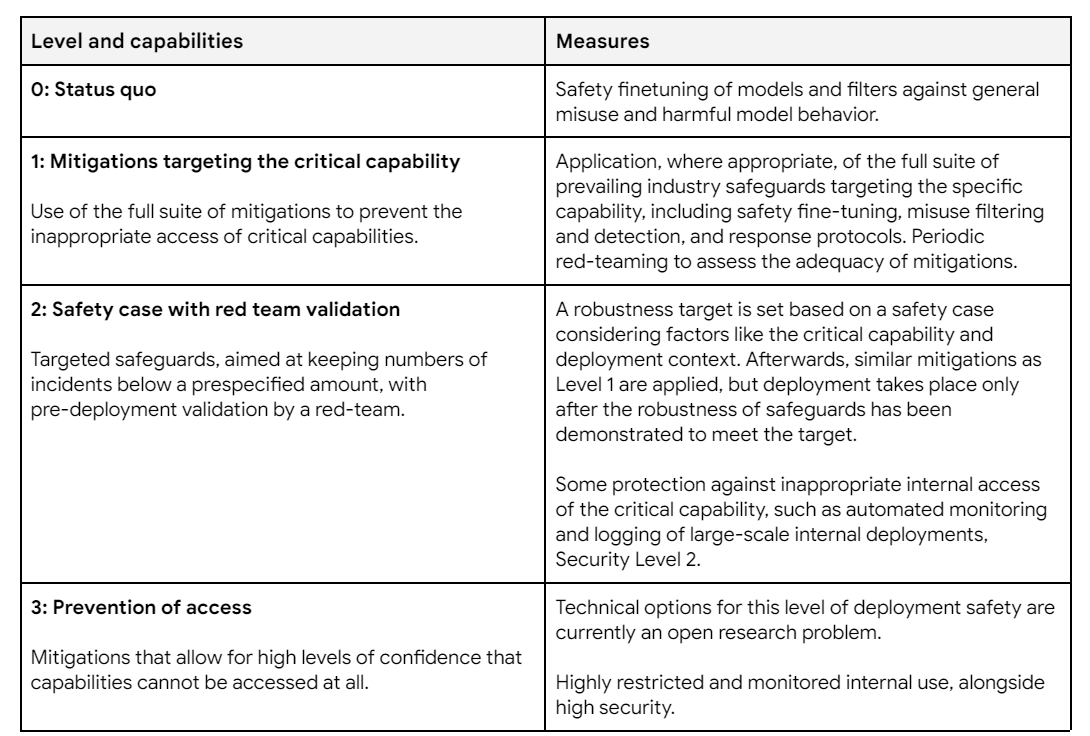

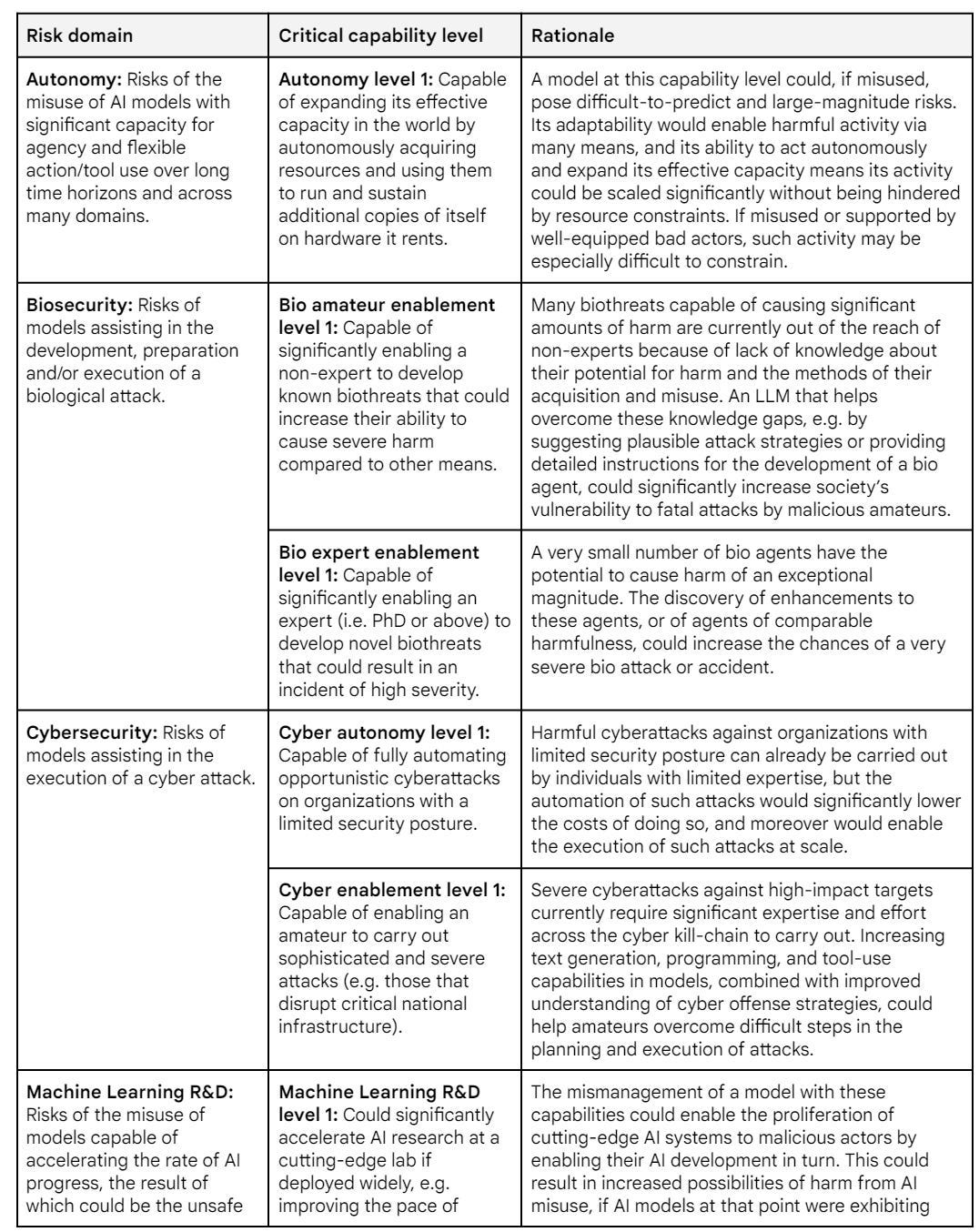

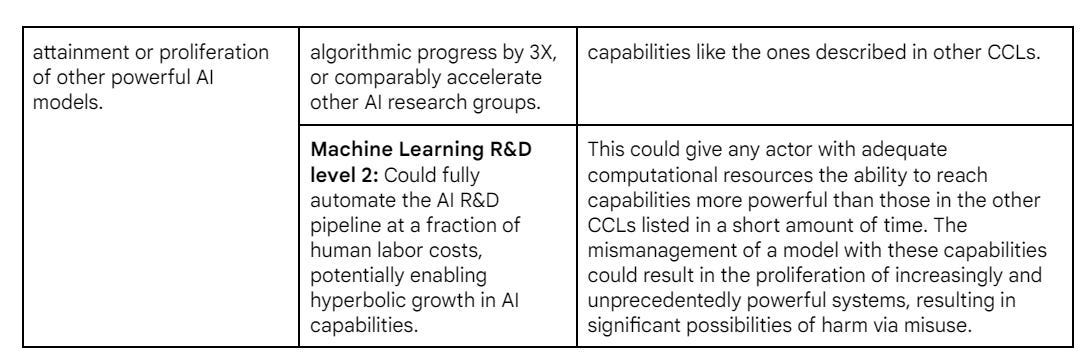

For example, OpenAI’s Preparedness Framework is well-drafted and thorough. But the company is under great commercial pressure, and teams implementing this framework may have little recourse if they find that they are given insufficient time to adequately complete their work.

If an employee realizes that the company has broken one of its commitments, they have no one to turn to but the company itself. There may be no anonymous reporting mechanisms for non-criminal activity, and strict confidentiality agreements prevent them from going public.

If the employee decides to go public nonetheless, they could be subject to retaliation. Historically at OpenAI, sign-on agreements threatened employees with the loss of their vested equity if they were fired for “cause”, which includes breach of confidentiality.

OpenAI has recently retracted this clause, and they deserve credit for this. But employees may still fear other forms of retaliation for disclosure, such as being fired and sued for damages.

In light of all of this, I and other current and former employees are calling for all frontier AI companies to provide assurances that employees will not be retaliated against for responsibly disclosing risk-related concerns.

My hope is that this will find support among a variety of groups, including the FAccT, open source and catastrophic risk communities – as well as among employees of AI companies themselves. I do not believe that these issues are specific to any one flavor of risk or harm.

Finally, I want to highlight that we are following in the footsteps of many others in this space, and resources such as the Signals Network and the Tech Worker Handbook are available to employees who want to learn more about whistleblowing.

Jeffrey Ladish: Heartening to see former and current employees of AI companies advocate for more transparency and whistleblower protections. I was pretty frustrated during the OpenAI board saga to hear so little from anyone about what the actual issues were about, and it’s been very illuminating hearing more details this past week.

At the time, I wondered why more employees or former employees didn’t speak out. I assumed it was mostly social pressure. And that was probably a factor, but now it appears an even bigger factor was the aggressive nondisclosure agreements OpenAI pressured former employees to sign.

You find out a lot when people finally have the right to speak out.

Or you could treat any request for any whistleblower protections this way:

Anton: absolutely incredible. “If the vibes are off we reserve the right to disseminate confidential information to whoever we feel like, for any reason.”

I can’t tell if this is mendacity or total lack of self-awareness. what else could be meant by carte blanche than being able to talk about anything to anyone at any time for any reason? is it just that you only plan to talk to the people you like?

No, they are absolutely not asking for that, nor is there any world where they get it.

Ideally there would be a company procedure, and if that failed there would be a regulator that could take the information in confidence, and act as the Reasonable Authority Figure if it came to that. Again, this is a strong reason for such an authority to exist. Ultimately, you try to find a compromise, but either the company is effectively sovereign over these issues, or it isn’t, so it’s hard.

The letter here is what happens after a company like OpenAI has proven itself not trustworthy and very willing to retaliate.

Alas, I do not think you can fully implement clause four here without doing more harm than good. I don’t think any promise not to retaliate is credible, and I think the threat of sharing confidential information will cause a lot of damage.

I do draw a distinction between retaliation within the company such as being fired, versus loss of equity, versus suing for damages. Asking that employees not get sued (or blackballed) for sounding the alarm, at a minimum, seems highly reasonable.

I do think we should apply other pressure to companies, including OpenAI, to have strong safety concern reporting procedures. And we should work to have a governmental system. But if that fails, I think as written Principle 4 here goes too far. I do not think it goes as badly as Joshua describes, it is not at all carte blanche, but I do think it goes too far. Instead we likely need to push for the first three clauses to be implemented for real, and then fall back on the true honor system. If things are bad enough, you do it anyway, and you take the consequences.

I also note that this all assumes that everyone else does not want to be called out if someone genuinely believes safety is at risk. Any sane version of Principle 4 has a very strong ‘you had better be right and God help you if you’re wrong or if the info you shared wasn’t fully necessary’ attached to it, for the reasons Joshua discusses.

Shouldn’t you want Amanda Askell in that room, exactly for the purpose of scuttling the launch if the launch needs to get scuttled?

Indeed, that is exactly what Daniel Kokotajlo did, without revealing confidential information. He took a stand, and accepted the consequences.

Lawrence Lessig, a lawyer now representing Daniel Kokotajlo and ten other OpenAI employees pro bono (what a mensch!) writes at CNN that AI risks could be catastrophic, so perhaps we should empower company workers to warn us about them. In particular, he cites Daniel Kokotajlo’s brave willingness to give up his equity and speak up, which led to many of the recent revelations about OpenAI.

Lessig calls for OpenAI and others to adapt the ‘right to warn’ pledge, described above.

As Lessig points out, you have the right to report illegal activity. But if being unsafe is not illegal, then you don’t get to report it. So this is one key way in which we benefit from better regulation. Even if it is hard to enforce, we at least allow reporting.

Also of note: According to Lessig, Altman’s apology and the restoration of Kokotajlo’s equity effectively tamped down attention to OpenAI’s ‘legal blunder.’ I don’t agree it was a blunder, and I also don’t agree the ploy worked. I think people remember, and that things seemed to die down because that’s how things work, people focus elsewhere after a few days.

What do you own, if you own OpenAI shares, or profit participation units?

I know what you do not want to own.

-

Nothing.

-

A share of OpenAI’s future profit distributions that you cannot sell.

Alas, you should worry about both of these.

The second worry is because:

-

There will be no payments for years, at least.

-

There are probably no payments, ever.

The first clause is obvious. OpenAI will spend any profits developing an AGI.

Then once it has an AGI, its terms say it does not have to hand over those profits.

Remember that they still have their unique rather bizarre structure. You do not even get unlimited upside, your profits are capped.

There is a reason you are told to ‘consider your investment in the spirit of a donation.’

Thus, the most likely outcome is that OpenAI’s shares are a simulacrum. It is a memecoin. Everything is worth what the customer will pay for it. The shares are highly valuable because other people will pay money for them.

There are two catches.

-

Those people need OpenAI’s permission to pay.

-

OpenAI could flat out take your shares, if it felt like it.

Hayden Field (CNBC): In at least two tender offers, the sales limit for former employees was $2 million, compared to $10 million for current employees.

…

For anyone who leaves OpenAI, “the Company may, at any time and in its sole and absolute discretion, redeem (or cause the sale of) the Company interest of any Assignee for cash equal to the Fair Market Value of such interest,” the document states.

Former OpenAI employees said that anytime they received a unit grant, they had to send a document to the IRS stating that the fair market value of the grant was $0. CNBC viewed a copy of the document. Ex-employees told CNBC they’ve asked the company if that means they could lose their stock for nothing.

OpenAI said it’s never canceled a current or former employee’s vested equity or required a repurchase at $0.

Whoops!

CNBC reports that employees and ex-employees are concerned. Most of their wealth is tied up in OpenAI shares. OpenAI now says it will not take away those shares no matter what and not use them to get people to sign restrictive agreements. They say they ‘do not expect to change’ the policy that everyone gets the same liquidity offers at the same price point.

That is not exactly a promise. Trust in OpenAI on such matters is not high.

Hayden Field (CNBC): former employee, who shared his OpenAI correspondence with CNBC, asked the company for additional confirmation that his equity and that of others was secure.

“I think there are further questions to address before I and other OpenAl employees can feel safe from retaliation against us via our vested equity,” the ex-employee wrote in an email to the company in late May. He added, “Will the company exclude current or former employees from tender events under any circumstances? If so, what are those circumstances?”

The person also asked whether the company will “force former employees to sell their units at fair market value under any circumstances” and what those circumstances would be. He asked OpenAI for an estimate on when his questions would be addressed, and said he hasn’t yet received a response. OpenAI told CNBC that it is responding to individual inquiries.

According to internal messages viewed by CNBC, another employee who resigned last week wrote in OpenAI’s “core” Slack channel that “when the news about the vested equity clawbacks provisions in our exit paperwork broke 2.5 weeks ago, I was shocked and angered.” Details that came out later “only strengthened those feelings,” the person wrote, and “after fully hearing leadership’s responses, my trust in them has been completely broken.”

…

“You often talk about our responsibility to develop AGI safely and to distribute the benefits broadly,” he wrote [to Altman]. “How do you expect to be trusted with that responsibility when you failed at the much more basic task” of not threatening “to screw over departing employees,” the person added.

…

“Ultimately, employees are going to become ex-employees,” Albukerk said. “You’re sending a signal that, the second you leave, you’re not on our team, and we’re going to treat you like you’re on the other team. You want people to root for you even after they leave.”

When you respond to the question about taking equity for $0 by saying you haven’t done it, that is not that different from saying that you might do it in the future.

Actually taking the equity for $0 would be quite something.

But OpenAI would not be doing something that unusual if it did stop certain employees from selling. Here for example is a recent story of Rippling banning employees working at competitors from selling. They say it was to ‘avoid sharing information.’

Thus, this seems like a wise thing to keep in mind:

Ravi Parikh: $1m in equity from OpenAI has far lower expected value than $1m in equity from Anthropic, Mistral, Databricks, etc

Why?

– you can only get liquidity through tender offers, not IPO or M&A, and the level to which you can participate is controlled by them (eg ex-employees can’t sell as much)

– they have the right to buy back your equity at any time for “fair market value”

– capped profit structure limits upside

OpenAI still might be a good place to work, but you should compare your offer there vs other companies accordingly.

How deep does the rabbit hole go? About this deep.

Jeremy Schlatter: There is a factor that may be causing people who have been released to not report it publicly:

When I received the email from OpenAI HR releasing me from the non-disparagement agreement, I wanted to publicly acknowledge that fact. But then I noticed that, awkwardly, I was still bound not to acknowledge that it had existed in the first place. So I didn’t think I could say, for example, “OpenAI released me from my non-disparagement agreement” or “I used to be bound by a non-disparagement agreement, but now I’m not.”

So I didn’t say anything about it publicly. Instead, I replied to HR asking for permission to disclose the previous non-disparagement agreement. Thankfully they gave it to me, which is why I’m happy to talk about it now. But if I hadn’t taken the initiative to email them I would have been more hesitant to reveal that I had been released from the non-disparagement agreement.

I don’t know if any other ex-OpenAI employees are holding back for similar reasons. I may have been unusually cautious or pedantic about this. But it seemed worth mentioning in case I’m not the only one.

William Saunders: Language in the emails included:

“If you executed the Agreement, we write to notify you that OpenAI does not intend to enforce the Agreement”

I assume this also communicates that OpenAI doesn’t intend to enforce the self-confidentiality clause in the agreement.

Oh, interesting. Thanks for pointing that out! It looks like my comment above may not apply to post-2019 employees.

(I was employed in 2017, when OpenAI was still just a non-profit. So I had no equity and therefore there was no language in my exit agreement that threatened to take my equity. The equity-threatening stuff only applies to post-2019 employees, and their release emails were correspondingly different.)

The language in my email was different. It released me from non-disparagement and non-solicitation, but nothing else:

“OpenAI writes to notify you that it is releasing you from any non-disparagement and non-solicitation provision within any such agreement.”

‘Does not intend to enforce’ continues to be language that would not give me as much comfort as I would like. Employees have been willing to speak out now, but it does seem like at least some of them are still holding back.

In related news on the non-disparagement clauses:

Beth Barnes: I signed the secret general release containing the non-disparagement clause when I left OpenAI. From more recent legal advice I understand that the whole agreement is unlikely to be enforceable, especially a strict interpretation of the non-disparagement clause like in this post. IIRC at the time I assumed that such an interpretation (e.g. where OpenAI could sue me for damages for saying some true/reasonable thing) was so absurd that couldn’t possibly be what it meant.

I sold all my OpenAI equity last year, to minimize real or perceived CoI with METR’s work. I’m pretty sure it never occurred to me that OAI could claw back my equity or prevent me from selling it.

OpenAI recently informally notified me by email that they would release me from the non-disparagement and non-solicitation provisions in the general release (but not, as in some other cases, the entire agreement.) They also said OAI “does not intend to enforce” these provisions in other documents I have signed. It is unclear what the legal status of this email is given that the original agreement states it can only be modified in writing signed by both parties.

As far as I can recall, concern about financial penalties for violating non-disparagement provisions was never a consideration that affected my decisions. I think having signed the agreement probably had some effect, but more like via “I want to have a reputation for abiding by things I signed so that e.g. labs can trust me with confidential information”. And I still assumed that it didn’t cover reasonable/factual criticism.

That being said, I do think many researchers and lab employees, myself included, have felt restricted from honestly sharing their criticisms of labs beyond small numbers of trusted people. In my experience, I think the biggest forces pushing against more safety-related criticism of labs are:

(1) confidentiality agreements (any criticism based on something you observed internally would be prohibited by non-disclosure agreements – so the disparagement clause is only relevant in cases where you’re criticizing based on publicly available information)

(2) labs’ informal/soft/not legally-derived powers (ranging from “being a bit less excited to collaborate on research” or “stricter about enforcing confidentiality policies with you” to “firing or otherwise making life harder for your colleagues or collaborators” or “lying to other employees about your bad conduct” etc)

(3) general desire to be researchers / neutral experts rather than an advocacy group.

Chris Painter: I have never owned equity in OpenAI, and have never to my knowledge been in any nondisparagement agreement with OpenAI.

Kelsey Piper: I am quite confident the contract has been widely retracted. The overwhelming majority of people who received an email did not make an immediate public comment. I am unaware of any people who signed the agreement after 2019 and did not receive the email, outside cases where the nondisparagement agreement was mutual (which includes Sutskever and likely also Anthropic leadership). In every case I am aware of, people who signed before 2019 did not reliably receive an email but were reliably able to get released if they emailed OpenAI HR.

If you signed such an agreement and have not been released, you can of course contact me on Signal: 303 261 2769.

I have been in touch with around a half dozen former OpenAI employees who I spoke to before former employees were released and all of them later informed me they were released, and they were not in any identifiable reference class such that I’d expect OpenAI would have been able to selectively release them while not releasing most people.

I, too, want a pony, but I am not VP of a huge pony training company. Also I do not actually want a pony.

Anna Makanju, OpenAI’s VP of Global Affairs: Anna Makanju, OpenAI’s vice-president of global affairs, told the Financial Times in an interview that its “mission” was to build artificial general intelligence capable of “cognitive tasks that are what a human could do today”.

“Our mission is to build AGI; I would not say our mission is to build superintelligence,” Makanju said.

You do not get to go on a mission to build AGI as quickly as possible and then pretend that ASI (superintelligence) is not implied by that mission.

This is in the context of a New York Magazine article about how Altman and other AI people used to admit that they noticed that what they were building will likely kill everyone, and now they have shut up about that in order to talk enterprise software.

The question is why. The obvious answer starts with the fact that by ‘AI industry’ here we mean Altman and OpenAI. There is a reason all the examples here are OpenAI. Anthropic still takes the problem seriously, messaging issues aside. Google never says anything either way. Meta was always lol I’m Meta. Altman has changed his tune. That does not constitute a global thesis.

The thesis of the article is that the warnings were hype and an excuse to raise the money, cynical lies that were abandoned when no longer useful.

The interesting new twist is to tie this to a broader story about ESG and DEI:

The AI industry’s sudden disinterest in the end of the world might also be understood as an exaggerated version of corporate America’s broader turn away from talking about ESG and DEI: as profit-driven, sure, but also as evidence that initial commitments to mitigating harmful externalities were themselves disingenuous and profit motivated at the time, and simply outlived their usefulness as marketing stories. It signals a loss of narrative control. In 2022, OpenAI could frame the future however it wanted. In 2024, it’s dealing with external expectations about the present, from partners and investors that are less interested in speculating about the future of mankind, or conceptualizing intelligence, than they are getting returns on their considerable investments, preferably within the fiscal year.

…

If its current leadership ever believed what they were saying, they’re certainly not acting like it, and in hindsight, they never really were. The apocalypse was just another pitch. Let it be a warning about the next one.

At least here it is symmetrical, with Altman (and unnamed others) having no underlying opinion either way, merely echoing whatever is useful at the time, the same way ESG and DEI were useful or caving to them was useful, and when it stopped being useful companies pulled back. There have been crazier theories. I think for ESG and DEI the shoe largely fits. But for AI this one is still pretty crazy.

The pitch ‘we care about the planet or about the disadvantaged or good governance or not getting blamed for not caring about them’ is often a good pitch, whatever your beliefs. Whereas I continue to not believe that ‘our product will likely kill everyone on Earth if we succeed’ was the brilliant marketing pitch people often claim it to have been. Altman’s comments, in particular, both require a real understanding and appreciation of the issues involved to say at all, and involved what were clearly in-context costly signals.

It is true that OpenAI has now revealed that it is going to act like a regular business. It is especially true that this is an excellent warning about the next story that Altman tries to sell to us.

What this does not do, even if the full narrative story was true, is tell us that ‘the apocalypse was just another pitch.’ Even if Sam Altman was making just another pitch, that does not mean that the pitch is false. Indeed, the pitch gets steadily better as it becomes more plausible. The truth is the best lie.

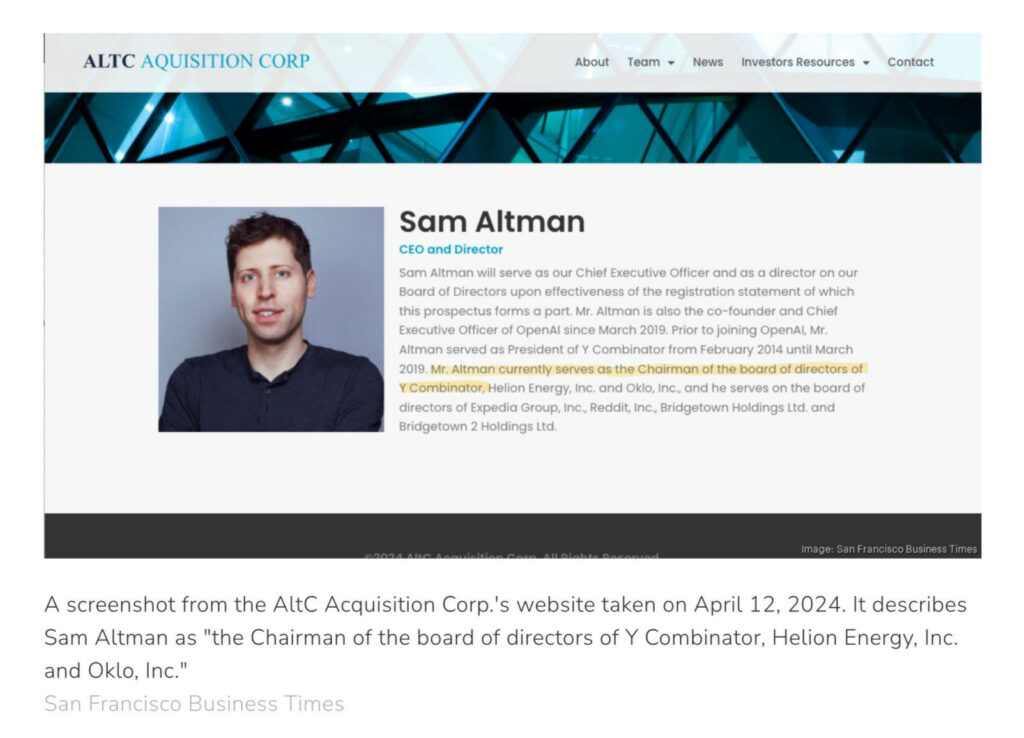

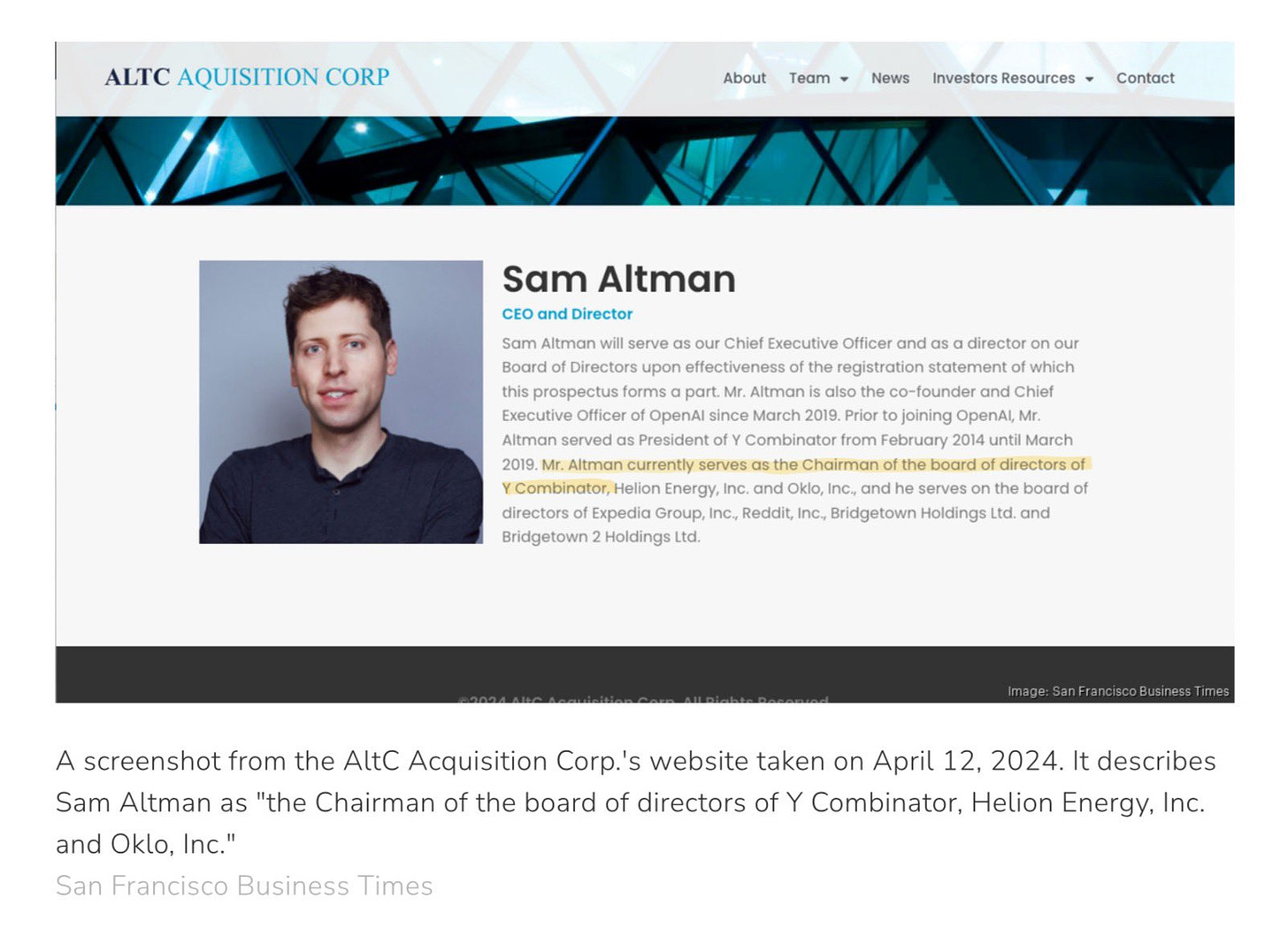

Which is odd, since YC says Sam Altman was never chairman of YC.

Sara Bloomberg: Whether Sam Altman was fired from YC or not, he has never been YC’s chair but claimed to be in SEC filings for his AltC SPAC which merged w/Oklo. AltC scrubbed references to Sam being YC chair from its website in the weeks since I first reported this.

Jacques: Huh. Sam added in SEC filings that he’s YC’s chairman. Cc Paul Graham.

“Annual reports filed by AltC for the past 3 years make the same claim. The recent report: Sam was currently chairman of YC at the time of filing and also “previously served” as YC’s chairman.”

Unclear if the SEC will try to do something about this. [offers info that the SEC takes such claims seriously if they are false, which very much matches my model of the SEC]

These posts have additional context. It seems it was originally the plan for Altman to transition into a chairman role in March 2019, but those plans were scrubbed quickly.

1010Towncrier (May 30): Does YC currently own OpenAI shares? That would provide more context for releases like this.

Paul Graham: Not that I know of.

Jacque: It apparently does [shows statement].

Paul Graham: That seems strange, because the for-profit arm didn’t exist before he was full-time, but I’ll ask around.

Apparently YC’s later-stage fund invested $10m in the for-profit subsidiary. This was not a very big investment for those funds. And obviously it wasn’t influencing me, since I found out about it 5 minutes ago.

It’s not that significant. If it were worth a billion dollars, I’d have known about it, because it would have a noticeable effect on predicted returns. But it isn’t and doesn’t.

OpenAI’s for-profit arm is a ‘capped profit,’ although they keep weakening the cap. So it makes sense that so far it didn’t get super big.

Shakeel: OpenAI now has *35in-house lobbyists, and will have 50 by the end of the year.

There is nothing unusual about a company hiring a bunch of lobbyists to shape the regulations it will face in the future. I only bring it up because we are under few illusions what the policy goals of these lobbyists are going to be.

They recently issued a statement on consumer privacy.

Your ChatGPT chats help train their models by default, but your ChatGPT Enterprise, ChatGPT Team and API queries don’t. You can also avoid helping by using temporary chats or you can opt-out.

They claim they do not ‘actively seek out’ personal information to train their models, and do not use public information to build profiles about people, advertise to or target them, or sell user data. And they say they work to reduce how much they train on personal information. That is good, also mostly much a ‘least you can do’ position.

The advertising decision is real. I don’t see a future promise, but for now OpenAI is not doing any advertising at all, and that is pretty great.

The New York Times confirms Microsoft has confirmed Daniel Kokotajlo’s claim that the early version of Bing was tested in India without safety board approval. Microsoft’s Frank Shaw had previously denied this.

Kevin Roose: For context: this kind of public walkback is very rare. Clearly not everyone at Microsoft knew (or wanted to say) that they had bypassed this safety board and used OpenAI’s model, but OpenAI folks definitely caught wind of it and were concerned.

Seems like a strange partnership!

I mean, yes, fair.

Mike Cook: I love all the breathless coverage of OpenAI ex-employees bravely speaking up like “after eight years of being overpaid to build the torment nexus, i now fear the company may have lost its way 😔” like thanks for the heads-up man we all thought it was super chill over there.

A little statue of a bay area guy in a hoodie with “in memory of those who did as little as humanly possible” on a plaque underneath, lest we forget.

Nathan Young: The high x-risk people seem to have a point here.

Trust isn’t enough. When it’s been broken, it may be too late. Feels like investing in AGI companies is often very asymmetric for people worried about AI risk.

What is the best counter argument here?

Michael Vassar: This has been obvious from the beginning of the behavior over a decade ago. It’s almost as if they weren’t being up front about their motives.

It was never a good plan.

The latest departure is Carroll Wainwright, cofounder of Metaculus, and one of the signers of the right to warn letter.

Carroll Wainwright: Last week was my final week working at OpenAI. This week I am signing a letter that calls upon frontier AI labs to support and protect employees who wish to speak out about AI risks and safety concerns.

I joined OpenAI because I wanted to help ensure that transformative AI technology transforms the world for the benefit of all. This is OpenAI’s mission, and it’s a mission that I strongly believe in.

OpenAI was founded as a non-profit, and even though it has a for-profit subsidiary, the for-profit was always supposed to be accountable to the non-profit mission. Over the last 6 months, my faith in this structure has significantly waned.

I worry that the board will not be able to effectively control the for-profit subsidiary, and I worry that the for-profit subsidiary will not be able to effectively prioritize the mission when the incentive to maximize profits is so strong.

With a technology as transformational as AGI, faltering in the mission is more than disappointing — it’s dangerous. If this happens, the duty will fall first to individual employees to hold it accountable.

AI is an emerging technology with few rules and regulations, so it is essential to protect employees who have legitimate concerns, even when there is no clear law that the company is breaking.

This is why I signed the letter at righttowarn.ai. AI companies must create protected avenues for raising concerns that balance their legitimate interest in maintaining confidential information with the broader public benefit.

OpenAI is full of thoughtful, dedicated, mission-driven individuals, which is why I am hopeful that OpenAI and other labs will adopt this proposal.

This post from March 28 claiming various no good high weirdness around the OpenAI startup fund is hilarious. The dives people go on. I presume none of it actually happened or we would know by now, but I don’t actually know.

Various technical questions about the Battle of the Board.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: I’d consider it extremely likely, verging on self-evident to anyone with C-level management experience, that we have not heard the real story about the OpenAI Board Incident; and that various principals are enjoined from speaking, either legally or by promises they are keeping.

The media spin during November’s events was impressive. As part of that spin, yes, Kara Swisher is an obnoxious hyperbolic (jerk) who will carry water for Sam Altman as needed and painted a false picture of November’s events. I muted her a long time ago because every time she talks my day gets worse. Every damn time.

Neel Nanda: During the OpenAI board debacle, there was a lot of media articles peddling the narrative that it was a safetyist coup. I think it’s pretty clear now that Altman was removed for being manipulative and dishonest, and likely that many of these articles were spread by journalists friendly to Altman. This is a good writeup of the lack of journalistic integrity shown by Kara Swisher and Co.

David Krueger says OpenAI cofounder Greg Brockman spoke about safety this way in 2016: “oh yeah, there are a few weirdos on the team who actually take that stuff seriously, but…” and that he was not the only one on the founding team with this perspective. Another OpenAI cofounder, John Schulman, says that doesn’t match John’s recollection of Greg’s views, and even if Greg did think that he wouldn’t have said it.

Gideon Futerman: When I started protesting OpenAI, whilst I got much support, I also got many people criticisng me, saying OpenAI were generally ‘on our side’, had someone say they are “80-90th percentile good”. I hope recent events have shown people that this is so far from true.

Another comment related to that first protest. When I spoke to Sam Altman, he said if the systems that OpenAI want to build had GPT-4 level alignment, he expected humanity would go extinct. However, he alluded to some future developments (ie Superalignment) as to why OpenAI could still continue to try to develop AGI.

Essentially, that was his pitch to me (notably not addressing some of our other issues as well). I was unconvinced at the time. Now both heads of the superalignment team have been forced out/quit.

It seems very difficult to claim OpenAI is ‘80th-90th percentile good’ now.

This still gives me a smile when I see it.