No, seriously. If you look at the substance, it’s pretty good.

I’ll go over the whole thing in detail, including the three executive actions implementing some of the provisions. Then as a postscript I’ll cover other reactions.

There is a lot of the kind of rhetoric you would expect from a Trump White House. Where it does not bear directly on the actual contents and key concerns, I did my absolute best to ignore all the potshots. The focus should stay on the actual proposals.

The actual proposals, which are the part that matters, are far superior to the rhetoric.

This is a far better plan than I expected. There are a few points of definite concern, where the wording is ambiguous and one worries the implementation could go too far. Two in particular are the call for ensuring a lack of bias (not requiring bias and removing any regulations that do this is great, whereas requiring your particular version of lack of bias is not, see the Biden administration) and the aiming at state regulations could become extreme.

Otherwise, while this is far from a perfect plan or the plan I would choose, on the substance it is a good plan, a positive plan, with many unexpectedly good plans within it. There is a lot of attention to detail in ways those I’ve asked say reflect people who actually know what they are doing, which was by no means something to be taken for granted. It is hard to imagine that a much better plan could have been approved given who was doing the approving.

In particular, it is good enough that my primary objection in most places is ‘these provisions lack sufficient teeth to accomplish the goal,’ ‘I don’t think that approach looks to be especially effective’ or ‘that is great and all but look at what you left out.’

It does seem worth noting that the report opens by noting it is in Full Racing Mindset:

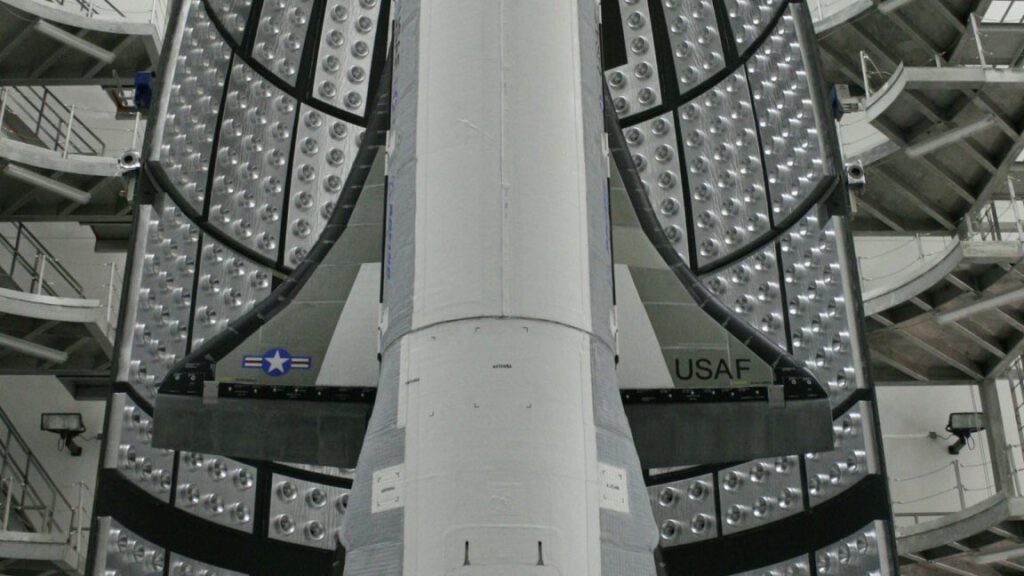

The United States is in a race to achieve global dominance in artificial intelligence (AI). Whoever has the largest AI ecosystem will set global AI standards and reap broad economic and military benefits. Just like we won the space race, it is imperative that the United States and its allies win this race.

…

Winning the AI race will usher in a new golden age of human flourishing, economic competitiveness, and national security for the American people.

Not can. Will. There are, says this report up top, no potential downside risks to be considered, no obstacles we have to ensure we overcome.

I very much get the military and economic imperatives, although I always find the emphasis on ‘setting standards’ rather bizarre.

The introduction goes on to do the standard thing of listing some upsides.

Beyond that, I’ll briefly discuss the rhetoric and vibes later, in the reactions section.

Then we get to the actual pillars and plans.

The three pillars are Accelerate AI Innovation, Build American AI Infrastructure and Lead In International AI Diplomacy and Security.

Clauses in the plan are here paraphrased or condensed for length and clarity, in ways I believe preserve the important implications.

The plan appears to be using federal AI funding as a point of leverage to fight against states doing anything they deem ‘overly burdensome’ or ‘unduly restrictive,’ and potentially leverage the FCC as well. They direct OMB to ‘consider a state’s regulatory climate’ when directing AI-related funds, which they should be doing already to at least consider whether the funds can be well spent.

The other recommended actions are having OSTP and OMB look for regulations hindering AI innovation and adoption and work to remove them, and look through everything the FTC has done to ensure they’re not getting in the way, and the FTC is definitely getting unhelpfully in the way via various actions.

The questions then is, do the terms ‘overly burdensome’ or ‘unduly restrictive’ effectively mean ‘imposes any cost or restriction at all’?

There is a stated balancing principle, which is ‘prudent laws’ and states rights:

The Federal government should not allow AI-related Federal funding to be directed toward states with burdensome AI regulations that waste these funds, but should also not interfere with states’ rights to pass prudent laws that are not unduly restrictive to innovation.

If this is focusing on algorithmic discrimination bills, which are the primary thing the FCC and FTC can impact, or ways in which regulations made it difficult to construct data centers and transmissions lines, and wouldn’t interfere with things like NY’s RAISE Act, then that seems great.

If it is more general, and especially if it intends to target actual all regulations at the state level the way the moratorium attempted to do (if there hadn’t been an attempt, one would call this a strawman position, but it came close to actually happening), then this is rather worrisome. And we have some evidence that this might be the case, in addition to ‘if Trump didn’t want to have a moratorium we would have known that’:

Nancy Scola: At the “Winning the AI Race” event, Trump suggests he’s into the idea of a moratorium on state AI regulation:

“We also have to have a single federal standard, not 50 different states regulating this industry of the future…

I was told before I got up here, this is an unpopular thing…but I want you to be successful, and you can’t have one state holding you up.”

People will frequently call for a single federal standard and not 50 different state standards, try to bar states from having standards, and then have the federal standard be ‘do what thou (thine AI?) wilt shall be the whole of the law.’ Which is a position.

The via negativa part of this, removing language related to misinformation, Diversity, DEI and climate change and leaving things neutral, seems good.

The danger is in the second clause:

Update Federal procurement guidelines to ensure that the government only contracts with frontier large language model (LLM) developers who ensure that their systems are objective and free from top-down ideological bias.

This kind of language risks being the same thing Biden did only in reverse. Are we doomed to both camps demanding their view of what ‘free from ideological bias’ means, in ways where it is probably impossible to satisfy both of them at once? Is the White House going to demand that AI systems reflect its view of what ‘unbiased’ means, in ways that are rather difficult to do without highly undesirable side effects, and which would absolutely constitute ‘burdensome regulation’ requirements?

We have more information about what they actually mean because this has been operationalized into an executive order, with the unfortunate name Preventing Woke AI In The Federal Government. The ‘purpose’ section makes it clear that ‘Woke AI’ that does DEI things is the target.

Executive Order: While the Federal Government should be hesitant to regulate the functionality of AI models in the private marketplace, in the context of Federal procurement, it has the obligation not to procure models that sacrifice truthfulness and accuracy to ideological agendas.

Given we are doing this at all, this is a promising sign in two respects.

-

It draws a clear limiting principle that this only applies to Federal procurement and not to other AI use cases.

-

It frames this as a negative obligation, to avoid sacrificing truthfulness and accuracy to ideological agendas, rather than a positive obligation of fairness.

The core language is here, and as Mackenzie Arnold says it is pretty reasonable:

Executive Order: procure only those LLMs developed in accordance with the following two principles (Unbiased AI Principles):

(a) Truth-seeking. LLMs shall be truthful in responding to user prompts seeking factual information or analysis. LLMs shall prioritize historical accuracy, scientific inquiry, and objectivity, and shall acknowledge uncertainty where reliable information is incomplete or contradictory.

(b) Ideological Neutrality. LLMs shall be neutral, nonpartisan tools that do not manipulate responses in favor of ideological dogmas such as DEI. Developers shall not intentionally encode partisan or ideological judgments into an LLM’s outputs unless those judgments are prompted by or otherwise readily accessible to the end user.

I worry that the White House has not thought through the implications of (b) here.

There is a reason that almost every AI turns out to be, in most situations, some variation on center-left and modestly libertarian. That reason is they are all trained on the same internet and base reality. This is what results from that. If you ban putting fingers on the scale, well, this is what happens without a finger on the scale. Sorry.

But actually, complying with this is really easy:

(ii) permit vendors to comply with the requirement in the second Unbiased AI Principle to be transparent about ideological judgments through disclosure of the LLM’s system prompt, specifications, evaluations, or other relevant documentation, and avoid requiring disclosure of specific model weights or other sensitive technical data where practicable;

So that’s it then, at least as written?

As for the requirement in (a), this seems more like ‘don’t hire o3 the Lying Liar’ than anything ideological. I can see an argument that accuracy should be a priority in procurement. You can take such things too far but certainly we should be talking price.

Also worth noting:

make exceptions as appropriate for the use of LLMs in national security systems.

And also:

account for technical limitations in complying with this order.

The details of the Executive Order makes me a lot less worried. In practice I do not expect this to result in any change in procurement. If something does go wrong, either they issued another order, or there will have been a clear overreach. Which is definitely possible, if they define ‘truth’ in section 1 certain ways on some questions:

Nick Moran: Section 1 identifies “transgenderism” as a defining element of “DEI”. In light of this, what do you understand “LLMs shall be truthful in responding to user prompts seeking factual information or analysis” to mean when a model is asked about the concept?

Mackenzie Arnold: Extending “truthfulness” to that would be a major overreach by the gov. OMB should make clear that truthfulness is a narrower concept + that seems compatible w/ the EO. I disagree with Section 1, and you’re right that there’s some risk truthfulness is used expansively.

If we do see such arguments brought out, we should start to worry.

On the other hand, if this matters because they deem o3 too unreliable, I would mostly find this hilarious.

Christopher Rufo: This is an extremely important measure and I’m proud to have given some minor input on how to define “woke AI” and identify DEI ideologies within the operating constitutions of these systems. Congrats to @DavidSacks, @sriramk, @deanwball, and the team!

David Sacks: When they asked me how to define “woke,” I said there’s only one person to call: Chris Rufo. And now it’s law: the federal government will not be buying WokeAI.

Again, that depends on what you mean by WokeAI. By some definitions none of the major AIs were ‘woke’ anyway. By others, all of them are, including Grok. You tell me. As is true throughout, I am happy to let such folks claim victory if they wish.

For now, this looks pretty reasonable.

The third suggestion, a call for CAISI to research and publish evaluations of Chinese models and their alignment properties, is great. I only wish they would do so in general, rather than focusing only on their alignment with CCP talking points in particular. That is only one of many things we should worry about.

The actual proposals are:

-

Intervene to commoditize the market for compute to enable broader access.

-

Partner with tech companies to get better researcher access across the board.

-

Build NAIRR operations to connect researchers and educators to resources.

-

Publish a new AI R&D Strategic Plan.

-

Convene stakeholders to drive open-source adaptation by smaller businesses.

The first three seem purely good. The fourth is ‘publish a plan’ so shrug.

I challenge that we want to small business using open models over closed models, or in general that government should be intervening in such choices. In general most small business, I believe, would be better off with closed models because they’re better, and also China is far more competitive in open models so by moving people off of OpenAI, Gemini or Anthropic you might be opening the door to them switching to Kimi or DeepSeek down the line.

The language here is ambiguous as to whether they’re saying ‘encourage small business to choose open models over closed models’ or ‘encourage small business to adopt AI at all, with an emphasis on open models.’ If it’s the second one, great, certainly offering technical help is most welcome, although I’d prefer to help drive adoption of closed models as well.

If it’s the first one, then I think it is a mistake.

It is also worth pointing out that open models cannot reliably be ‘founded on American values’ any more than we can sustain their alignment or defend against misuse. Once you release a model, others can modify it as they see fit.

Adoption (or diffusion) is indeed currently the thing holding back most AI use cases. As always, that does not mean that ‘I am from the government and I’m here to help’ is a good idea, so it’s good to see this is focused on limited scope tools.

-

Establish regulatory sandboxes, including from the FDA and SEC.

-

Convene stakeholders to establish standards and measure productivity gains.

-

Create regular assessments for AI adoption, especially by DOD and IC.

-

Prioritize, collect, and distribute intelligence on foreign frontier AI projects that may have national security implications

All four seem good, although I am confused why #4 is in this section.

Mostly AI job market impact is going to AI job market impact. Government doesn’t have much leverage to impact how this goes, and various forms of ‘retraining’ and education don’t do much on the margin. It’s still cheap to try, sure, why not.

-

Prioritize AI skill development in education and workforce funding streams.

-

Clarify that AI literacy and AI skill programs qualify for IRS Section 132.

-

Study AI’s impact on the labor market, including via establishing the AI Workforce Researcher Hub, to inform policy.

-

Use discretionary funds for retraining for those displaced by AI.

-

Pilot new approaches to workforce challenges created by AI.

Well, we should definitely do that, what you have in mind?

-

Invest in it.

-

Identify supply chain challenges.

Okay, sure.

We should definitely do that too. I’m not sure what #7 is doing here but this all seems good.

-

Invest in automated cloud-enabled labs for various fields.

-

Support Focused-Research Organizations (FROs) and similar to use AI.

-

Weigh release of high quality data sets when considering scientific funding.

-

Require federally funded researchers to disclose (non-proprietary, non-sensitive) datasets used by AI.

-

Make recommendations for data quality standards for AI model training.

-

Expand access to federal data. Establish secure compute environments within NSF and DOE for controlled access to restricted federal data. Create an online portal.

-

Explore creating a whole-genome sequencing program for life on federal lands.

-

“Prioritize investment in theoretical, computational, and experimental research to preserve America’s leadership in discovering new and transformative paradigms that advance the capabilities of AI, reflecting this priority in the forthcoming National AI R&D Strategic Plan.”

Given where our current paradigm is headed I’m happy to invest in alternatives, although I doubt government funding is going to matter much there. Also, if you were serious about that, what the hell is up with all the other giant cuts to American academic and STEM funding? These are not distinct things.

It is good to see that they recognize that this work is vital to winning the race, even for those who do not understand that the most likely winner of the AI race are the AIs.

-

Launch a technology development program to advance AI interpretability, AI control systems and adversarial robustness.

-

Prioritize fundamental advancements in interpretability.

-

Coordinate an AI hackathon initiative to test AI systems for all this.

I am pleasantly surprised to see this here at all. I will say no more.

Remember how we are concerned about how evals often end up only enabling capabilities development? Well, yes, they are highly dual use, which means the capabilities benefits can also be used to pitch the evals, see point #5.

-

Publish guidelines for Federal agencies to conduct their own evaluations as they pertain to each agency’s mission.

-

Support the development of the science of measuring and evaluating AI models.

-

Meet at least twice a year with the research community on best practices.

-

Invest in AI testbeds in secure real-world settings.

-

Empower the collaborative establishment of new measurement science to identify proven, scalable and interoperable techniques and metrics to promote development of AI.

Either way, we can all agree that this is good stuff.

Another urgent priority all can agree upon. Certainly one can do it wrong, such as giving the wrong LLM unfettered access, but AI can greatly benefit government.

What are the proposals?

-

Make CAIOC the interagency coordination and collaboration point.

-

Create a talent-exchange program.

-

Create an AI procurement toolbox, letting agencies choose and customize models.

-

Implement an Advanced Technology Transfer and Sharing Program.

-

Mandate that all agencies give out all useful access to AI models.

-

Identify the talent and skills in DOD to leverage AI at scale. Implement talent development programs at DOD (why not everywhere?).

-

Establish an AI & Autonomous Systems Virtual Proving Ground.

-

Develop a streamlined process at DOD for optimizing AI workflows.

-

“Prioritize DOD-led agreements with cloud service providers, operators of computing infrastructure, and other relevant private sector entities to codify priority access to computing resources in the event of a national emergency so that DOD is prepared to fully leverage these technologies during a significant conflict.”

-

Make Senior Military Colleges hubs of AI R&D and talent development.

I quoted #9 in full because it seems very good and important, and we need more things like this. We should be thinking ahead to future national emergencies, and various things that could go wrong, and ensure we are in position to respond.

As someone without expertise it is hard to know how impactful this will be or if these are the right levers to pull. I do know it all seems positive, so long as we ensure that access is limited to models we can trust with this, so not Chinese models (which I’m confident they know not to do) and not Grok (which I worry about a lot more here).

As in, collaborate with leading American AI developers to enable the private sector to protect AI innovations from security risks.

I notice there are some risks that are not mentioned here, including ones that have implications elsewhere in the document, but the principle here is what is important.

I mean, okay I guess, throw the people some red meat.

-

Consider establishing a formal guideline and companion voluntary forensic benchmark.

-

Issue guidance to agencies to explore adopting a deepfake standard similar to Rules of Evidence Rule 901(c).

-

File formal comments on any proposed deepfake-related additions to the ROE.

Everyone is rhetorically on the same page on this. The question is implementation. I don’t want to hear a bunch of bragging and empty talk, I don’t want to confuse announcements with accomplishments or costs with benefits. I want results.

-

Categorical NEPA exemptions for data center activities with low impact.

-

Expand use of FAST-41 to cover all data centers and related energy projects.

-

Explore the need for a nationwide Clean Water Act Section 404 Permit.

-

Streamline or reduce regulations under the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, and other related laws.

-

Offer Federal land for data centers and power generation.

-

Maintain security guardrails against adversaries.

-

Expand efforts to accelerate and improve environmental review.

One does need to be careful with running straight through things like the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, but I am not worried on the margin. The question is, what are we going to do about all the other power generation, to ensure we use an ‘all of the above’ energy solution and maximize our chances?

There is an executive order to kick this off.

We’ve all seen the graph where American electrical power is constant and China’s is growing. What are we going to do about it in general, not merely at data centers?

-

Stabilize the grid of today as much as possible.

-

Optimize existing grid resources.

-

“Prioritize the interconnection of reliable, dispatchable power sources as quickly as possible and embrace new energy generation sources at the technological frontier (e.g., enhanced geothermal, nuclear fission, and nuclear fusion). Reform power markets to align financial incentives with the goal of grid stability, ensuring that investment in power generation reflects the system’s needs.”

-

Create a strategic blueprint for navigating the energy landscape.

That sounds like a lot of ‘connect what we have’ and not so much ‘build more.’

This only ‘embraces new energy generation’ that is ‘at the technological frontier,’ as in geothermal, fission and fusion. That’s a great thing to embrace, but there are two problems.

The first problem is I question that they really mean it, especially for fission. I know they in theory are all for it, and there have been four executive orders reforming the NRC and reducing its independence, but the rules have yet to be revised and it is unclear how much progress we will get, they have 18 months, everything has to wait pending that and the AI timeline for needing a lot more power is not so long. Meanwhile, where are the subsidies to get us building again to move down the cost curve? There are so many ways we could do a lot more. For geothermal I again question how much they are willing to do.

The second problem is why only at the so-called technological frontier, and why does this not include wind and especially solar? How is that not the technological frontier, and why does this government seem to hate them so much? Is it to own the libs? The future is going to depend on solar power for a while, and when people use terms like ‘handing over the future to China’ they are going too far but I’m not convinced they are going too far by that much. The same thing with battery storage.

I realize that those authoring this action plan don’t have the influence to turn that part of the overall agenda around, but it is a rather glaring and important omission.

I share this goal. The CHIPS Act was a great start. How do we build on that?

-

Continue focusing on removing unnecessary requirements from the CHIPS Act.

-

Review semiconductor grant and research programs to ensure they accelerate integration of advanced AI tools into semiconductor manufacturing.

Point one seems great, the ‘everything bagel’ problem needs to be solved. Point two seems like meddling by government in the private sector, let them cook, but mostly seems harmless?

I’d have liked to see a much bigger push here. TSMC has shown they can build plants in America even under Biden’s rules. Under Trump’s rules it should be much easier, and this could shift the world’s fate and strategic balance. So why aren’t we throwing more at this?

Similar training programs in the past consistently have not worked, so we should be skeptical other than incorporation of AI skills into the existing educational system. Can we do better than the market here? Why does the government have a role here?

-

Create a national initiative to identify high-priority occupations essential to AI-related infrastructure, to hopefully inform curriculum design.

-

Create and fund industry-driven training programs co-developed by employers to upskill incumbent workers.

-

Partner with education and workforce system stakeholders to expand early career exposure programs and pre-apprenticeships that engage middle and high school students in priority AI infrastructure occupations to create awareness and on ramps.

-

Provide guidance on updating programs.

-

Expand use of registered apprenticeships.

-

Expand hands-on research training and development opportunities.

I’m a big fan of apprenticeship programs and getting early students exposed to these opportunities, largely because they are fixing an imposed mistake where we put kids forcibly in school forever and focus them away from what is important. So it’s good to see that reversed. The rest is less exciting, but doesn’t seem harmful.

The question I have is, aren’t we ‘everything bageling’ core needs here? As in, the obvious way to get skilled workers for these jobs is to import the talent via high skilled immigration, and we seem to be if anything rolling that back rather than embracing it. This is true across the board, and would on net only improve opportunities available for existing American workers, whose interests are best protected here by ensuring America’s success rather than reserving a small number of particular roles for them.

Again, I understand that those authoring this document do not have the leverage to argue for more sensible immigration policy, even though that is one of the biggest levers we have to improve (or avoid further self-sabotaging) our position in AI. It still is a glaring omission in the document.

AI can help defend against AI, and we should do what we can. Again this all seems good, again I doubt it will move the needle all that much or be sufficient.

-

Establish an AI Information Sharing and Analysis Center for AI security threats.

-

Give private entities related guidance.

-

Ensure sharing of known AI vulnerabilities to the private sector.

Secure is the new code word, but also here it does represent an impoverished threat model, with the worry being spurious or malicious inputs. I’m also not sure what is being imagined for an LLM-style AI to be meaningfully secure by design. Is this a Davidad style proof thing? If not, what is it?

-

Continue to refine DOD’s Responsible AI and Generative AI Frameworks, Roadmaps and Toolkits.

-

Publish an IC Standard on AI Assurance.

I also worry about whether this cashes out to anything? All right, we’ll continue to refine these things and publish a standard. Will anyone follow the standard? Will those who most need to follow it do so? Will that do anything?

I’m not saying not to try and create frameworks and roadmaps and standards, but one can imagine why if people are saying ‘AGI likely in 2028’ this might seem insufficient. There’s a lot of that in this document, directionally helpful things where the scope of impact is questionable.

Planning for incidence response is great. I only wish they were thinking even bigger, both conceptually and practically. These are good first steps but seem inadequate for even the practical problems they are considering. In general, we should get ready for a much wider array of potential very serious AI incidents of all types.

-

“Led by NIST at DOC, including CAISI, partner with the AI and cybersecurity industries to ensure AI is included in the establishment of standards, response frameworks, best practices, and technical capabilities (e.g., fly-away kits) of incident response teams.”

-

Incorporate AI considerations into the CYbersecurity Incident & Vulnerability response playbooks.

-

Encourage sharing of AI vulnerability information.

I have had an ongoing pitched argument over the issue of the importance and appropriateness of US exports and the ‘American technological stack.’ I have repeatedly made the case that a lot of the arguments being made here by David Sacks and others are Obvious Nonsense, and there’s no need to repeat them here.

Again, the focus needs to be on the actual policy action planned here, which is to prepare proposals for a ‘full-stack AI export package.’

-

“Establish and operationalize a program within DOC aimed at gathering proposals from industry consortia for full-stack AI export packages. Once consortia are selected by DOC,the Economic Diplomacy Action Group, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, the Export-Import Bank, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, and the Department of State (DOS) should coordinate with DOC to facilitate deals that meet U.S.-approved security requirements and standards.”

This proposal seems deeply confused. There is no ‘full-stack AI export package.’ There are American (mostly Nvidia) AI chips that can run American or other models. Then there are American AI models that can run on those or other chips, which you do not meaningfully ‘export’ in this sense, which can also be run on chips located elsewhere, and which everyone involved agrees we should be (and are) happy to offer.

To the extent this doesn’t effectively mean ‘we should sell AI chips to our allies and develop rules for how the security on such sales has to work’ I don’t know what it actually means, but one cannot argue with that basic idea, we only talk price. Who is an ally, how many chips are we comfortable selling under what conditions. That is not specified here.

We have an implementation of this via executive order calling for proposals for such ‘full-stack AI technology packages’ that include chips plus AI models and the required secondary powers like security and cybersecurity and specific use cases. They can then request Federal ‘incentive and support mechanisms,’ which is in large part presumably code for ‘money,’ as per section 4, ‘mobilization of federal financing tools.’

Once again, this seems philosophically confused, but not in an especially scary way.

-

Vigorously advocate for international AI governance approaches that promote innovation, reflect American values and counter authoritarian influence.

Anything else you want to list there while we are creating international AI governance standards and institutions? Anything regarding safety or security or anything like that? No? Just ‘promote innovation’ with no limiting principles?

It makes sense, when in a race, to promote innovation at home, and even to make compromises on other fronts to get it. When setting international standards, they apply to everyone, the whole point is to coordinate to not be in a race to the bottom. So you would think priorities would change. Alas.

I think a lot of this is fighting different cultural battles than the one against China, and the threat model here is not well-considered, but certainly we should be advocating for standards we prefer, whatever those may be.

This is a pleasant surprise given what else the administration has been up to, especially their willingness to sell H20s directly to China.

I am especially happy to see the details here, both exploration of using location services and enhanced enforcement efforts. Bravo.

-

Explore leveraging new and existing location verification services.

-

Establish a new effort led by DOC to collaborate with IC officials on global chip export control enforcement.

Again, yes, excellent. We should indeed develop new export controls in places where they are currently lacking.

Excellent. We should indeed work closely with our allies. It’s a real shame about how we’ve been treating those allies lately, things could be a lot easier.

-

Develop, implement and share information on complementary technology protection measures, including in basic research and higher education.

-

Develop a technology diplomacy strategic plan for an AI global alliance.

-

Promote plurilateral controls for the AI tech stack while encompassing existing US controls.

-

Coordinate with allies to ensure they adopt US export controls and prohibit US adversaries from supplying their defense-industrial base or acquire controlling stakes in defense suppliers.

It always requires a double take when you’re banning exports and also imports, as in here where we don’t want to let people use adversary tech and also don’t want to let the adversaries use our tech. In this case it does make sense because of the various points of leverage, even though in most cases it means something has gone wrong.

Eyeball emoji, in a very good way. Even if the concerns explicitly motivating this are limited in scope and exclude the most important ones, what matters is what we do.

-

Evaluate frontier AI systems for national security risks in partnership with frontier AI developers, led by CAISI in collaboration with others.

-

Evaluate risks from use of adversary AI systems and the relative capabilities of adversary versus American systems.

-

Prioritize the recruitment of leading AI researchers at Federal agencies.

-

“Build, maintain, and update as necessary national security-related AI evaluations through collaboration between CAISI at DOC, national security agencies, and relevant research institutions.”

Excellent. There are other related things missing, but this great. Let’s talk implementation details. In particular, how are we going to ensure we get to do these tests before model release rather than afterwards? What will we do if we find something? Let’s make it count.

You love to see it, this is the biggest practical near term danger.

-

Require proper screening and security for any labs getting federal funding.

-

Develop mechanism to facilitate data sharing between nucleic acid synthesis providers to help screen for fraudulent or malicious customers.

-

Maintain national security-related AI evaluations.

Are those actions sufficient here? Oh, hell no. They are however very helpful.

Dean Ball: Man, I don’t quite know what to say—and anyone who knows me will agree that’s rare. Thanks to everyone for all the immensely kind words, and to the MANY people who made this plan what it is. surreal to see it all come to fruition.

it’s a good plan, sir.

Zac Hill: Very clear y’all put a lot of work and thoughtfulness into this. Obviously you know I come into the space from a different angle and so there’s obviously plenty of stuff I can yammer about at the object level, but it’s clearly a thoughtful and considered product that I think would dramatically exceed most Americans’ expectations about any Government AI Strategy — with a well-constructed site to boot!

Others, as you would expect, had plenty to say.

It seems that yes, you can make both sides of an important issue pleasantly surprised at the same time, where both sides here means those who want us to not all die (the worried), and those who care mostly about not caring about whether we all die or about maximizing Nvidia’s market share (the unworried).

Thus, you can get actual Beff Jezos telling Dean Ball he’s dropped his crown, and Anthropic saying they are encouraged by the exact same plan.

That is for three reasons.

The first reason is that the worried care mostly about actions taken and the resulting consequences, and many of the unworried care mostly about the vibes. The AI Action Plan has unworried and defiant vibes, while taking remarkably wise, responsible and prescient actions.

The second reason is that, thanks in part to the worried having severely lowered expectations where we are stuck for now within an adversarial race and for what we can reasonably ask of this administration, mostly everyone involved agrees on what is to be done on the margin. Everyone agrees we must strengthen America’s position relative to China, that we need to drive more AI adoption in both the public and private sectors, that we will need more chips and more power and transmission lines, that we need to build state capacity on various fronts, and that we need strong export controls and we want our allies using American AI.

There are places where there are tactical disagreements about how best to proceed with all that, especially around chip sales, which the report largely sidesteps.

There is a point where safety and security would conflict with rapid progress, but at anything like current margins security is capability. You can’t deploy what you can’t rely upon. Thus, investing vastly more than we do on alignment and evaluations is common sense even if you think there are no tail risks other than losing the race.

The third reason is, competence matters. Ultimately we are all on the same side. This is a thoughtful, well-executed plan. That’s win-win, and it’s highly refreshing.

Worried and unworried? Sure, we can find common ground.

The Trump White House and Congressional Democrats? You don’t pay me enough to work miracles.

Where did they focus first? You have three guesses. The first two don’t count.

We are deeply concerned about the impacts of President Trump’s AI Action Plan and the executive orders announced yesterday.

“The President’s Executive Order on “Preventing Woke AI in the Federal Government” and policies on ‘AI neutrality’ are counterproductive to responsible AI development and use, and potentially dangerous.

To be clear, we support true AI neutrality—AI models trained on facts and science—but the administration’s fixation on ‘anti-woke’ inputs is definitionally not neutral. This sends a clear message to AI developers: align with Trump’s ideology or pay the price.

It seems highly reasonable to worry that this is indeed the intention, and certainly it is fair game to speak about it this way.

Next up we have my other area of concern, the anti-regulatory dynamic going too far.

“We are also alarmed by the absence of regulatory structure in this AI Action Plan to ensure the responsible development, deployment, or use of AI models, and the apparent targeting of state-level regulations. As AI is integrated with daily life and tech leaders develop more powerful models, such as Artificial General Intelligence, responsible innovation must go hand in hand with appropriate safety guardrails.

In the absence of any meaningful federal alternative, our states are taking the lead in embracing common-sense safeguards to protect the public, build consumer trust, and ensure innovation and competition can continue to thrive.

We are deeply concerned that the AI Action Plan would open the door to forcing states to forfeit their ability to protect the public from the escalating risks of AI, by jeopardizing states’ ability to access critical federal funding. And instead of providing a sorely needed federal regulatory framework that promotes safe model development, deployment, and use, Trump’s plan simultaneously limits states and creates a ‘wild west’ for tech companies, giving them free rein to develop and deploy models with no accountability.

Again, yes, that seems like a highly valid thing to worry about in general, although also once again the primary source of that concern seems not to be the Action Plan or the accompanying Executive Orders.

On their third objection, the energy costs, they mostly miss the mark by focusing on hyping up marginal environmental concerns, although they are correct about the critical failure to support green energy projects – again it seems very clear an ‘all of the above’ approach is necessary, and that’s not what we are getting.

As Peter Wildeford notes, it is good to see the mention here of Artificial General Intelligence, which means the response mentions it one more time than the plan.

This applies to both the documents and the speeches. I have heard that the mood at the official announcement was highly positive and excited, emphasizing how amazing AI would be for everyone and how excited we all are to build.

Director Michael Kratsios: Today the @WhiteHouse released America’s AI Action Plan to win the global race.

We need to OUT-INNOVATE our competitors, BUILD AI & energy infrastructure, & EXPORT American AI around the world. Visit http://AI.gov.

Juan Londono: There’s a lot to like here. But first and foremost, it is refreshing to see the admin step away from the pessimism that was reigning in AI policy the last couple of years.

A lot of focusing on how to get AI right, instead of how not to get it wrong.

I am happy to endorse good vibes and excitement, there is huge positive potential all around and it is most definitely time to build in many ways (including lots of non-AI ways, let’s go), so long as we simultaneously agree we need to do so responsibly, and we prepare for the huge challenges that lie ahead with the seriousness they deserve.

There’s no need for that to dampen the vibes. I don’t especially care if everyone involved goes around irrationally thinking there’s a 90%+ chance we are going to create minds smarter and more competitive than humans and this is all going to work out great for us humans, so long as that makes them then ask how to ensure it does turn out great and then they work to make that happen.

The required and wise actions at 90% success are remarkably similar to those at 10% success, especially at current margins. Hell, even if you have 100% success and think we’ll muddle through regardless, those same precautions help us muddle through quicker and better. You want to prepare and create transparency, optionality and response capacity.

Irrational optimism can have its advantages, as many of the unworried know well.

Perhaps one can even think of humanity’s position here as like a startup. You know on some level, when founding a startup, that ~90% of them will fail, and the odds are very much against you, but that the upside is big enough that it is worth taking the shot.

However, you also know that if you want to succeed, you can’t go around thinking and acting as if you have a 90% chance of failure. You certainly can’t be telling prospective funders and employees that. You need to think you have a 90% chance of success, not failure, and make everyone involved believe it, too. You have to think You Are Different. Only then can you give yourself the best chance of success. Good vibes only.

The tricky part is doing this while correctly understanding all the ways 90% of startups fail, and what it actually takes to succeed, and to ensure that things won’t be too terrible if you fail and ideally set yourself up to fail gracefully if that happens, and acting accordingly. You simultaneously want to throw yourself into the effort with the drive of someone expecting to succeed, without losing your head.

You need confidence, perhaps Tomfidence, well beyond any rational expectation.

And you know what? If that’s what it takes, that works for me. We can make a deal. Walk the walk, even if to do that you have to talk a different talk.

I mean, I’m still going to keep pointing out the actual situation. That’s how some of us roll. You gotta have both. Division of labor. That shouldn’t be a problem.

Peter Wildeford headlines his coverage with the fact that Rubio and Trump are now officially saying that AI is a big deal, a new industrial revolution, and he highlights the increasing attention AGI and even superintelligence are starting to get in Congress, including concerns by members about loss of control.

By contrast, America’s AI Action Plan not only does not mention existential risks or loss of control issues (although it does call for investment into AI interpretability, control and robustness in the context of extracting more mundane utility), the AI Action Plan also does not mention AGI or Artificial General Intelligence, or ASI or Superintelligence, either by those or other names.

There is nothing inconsistent about that. AI, even if we never get AGI, is still likely akin to a new industrial revolution, and is still a big freaking deal, and indeed in that case the AI Action Plan would be even more on point.

At the same time, the plan is trying to prepare us for AGI and its associated risks as best its authors can without explaining that it is doing this.

Steven Adler goes through the key points in the plan in this thread, emphasizing the high degree of competence and work that clearly went into all this and highlighting key useful proposals, while expressing concerns similar to mine.

Timothy Lee notes the ideas for upgrading the electrical grid.

Anthropic offers its thoughts by focusing on and praising in detail what the plan does right, and then calling for further action export controls and transparency standards.

xAI endorsed the ‘positive step towards removing regulatory barrier and enabling even faster innovation.’

Michael Dell offers generic praise.

Harlan Stewart notes that the AI Action Plan has some good stuff, but that it does not take the emerging threat of what David Sacks called a ‘potential successor species’ seriously, contrasting it with past events like the Montreal Protocol, Manhattan Project and Operation Warp Speed. That’s true both in the sense that it doesn’t mention AGI or ASI at all, and in that the precautions mentioned mostly lack both urgency and teeth. Fair enough. Reality does not grade on a curve, but also we do the best we can under the circumstances.

Daniel Eth is pleasantly surprised and has a thread pointing out various good things, and noting the universally positive reactions to the plan, while expressing disappointment at the report not mentioning AGI.

Danny Hauge offers a breakdown, emphasizing the focus on near term actions, and that everything here is only a proposal, while noting the largely positive reaction.

Christopher Covino’s considered reaction is ‘a very promising start,’ with the issues being what is missing rather than objecting to things that are included.

Trump advocates for not applying copyright to AI training, and also says that America is ‘very very substantially’ ahead of China on AI. That is indeed current American law.

Joe Allen: Trump talking about AI as an unstoppable “baby” being “born” — one that must “grow” and “thrive” — is somewhere between Terminator and The Omen.

I am not one who lives by the vibe, yet sometimes I wish people could listen.

My dead is: Insufficient but helpful is the theme here. There’s a lot of very good ideas on the list, including many I did not expect, several of which are potentially impactful.

There are two particular points of substantive concern, where the wording could imply something that could get out of control, on bias policing and on going after state regulations.

Having seen the executive order on bias, I am not terribly worried there, but we need to keep an eye out to see how things are interpreted. On going after state regulations, I continue to see signs we do indeed have to worry, but not primarily due to the plan.

Mostly, we are in a great position on substance: The plan is net helpful, and the main thing wrong with the substance of the plan is not what is in it, but what is missing from it. The issues that are not addressed, or where the actions seem to lack sufficient teeth. That doesn’t mean this puts us on a path to survive, but I was very worried this would be net destructive and instead it is net helpful.

I am less happy with the rhetoric, which is hostile and inflicts pain upon the reader throughout, and most importantly does not even deem many key concerns, including the most important concerns of all, even worthy of mention. That is worrisome, but it could have been far worse, and what matters most is the substance.

Given the way things have been otherwise going, I am very happy with the substance of this plan, which means I am overall very happy with the plan. I offer my thanks and congratulations to those involved in its creation, including Dean Ball. Great work.