NASA likely to significantly delay the launch of Crew 9 due to Starliner issues

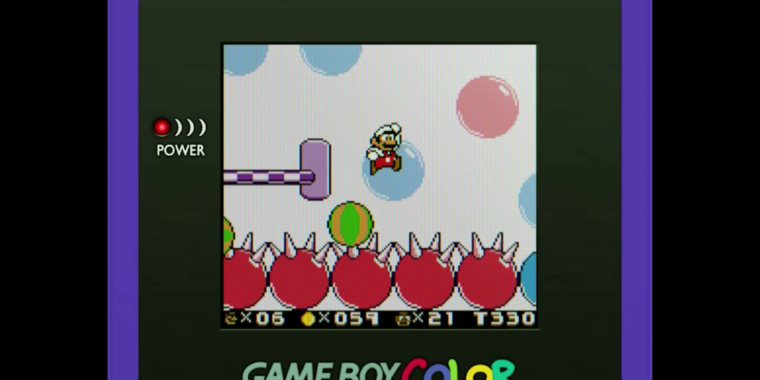

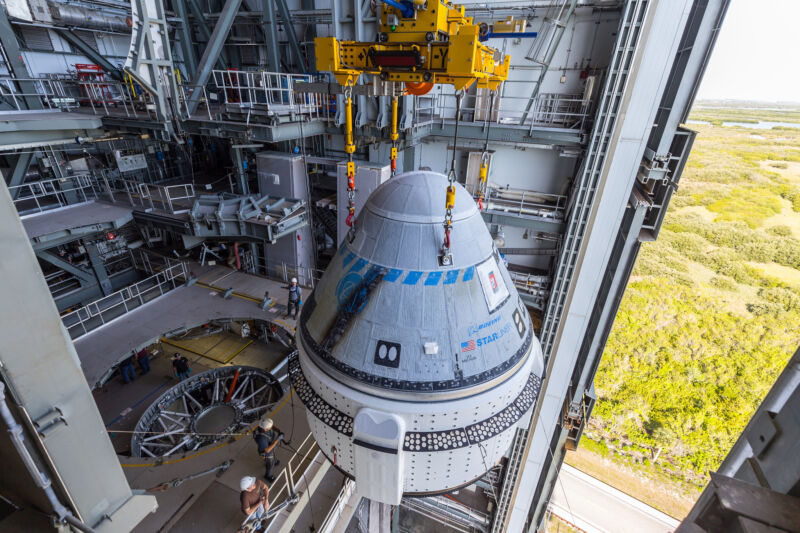

Enlarge / Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft is lifted to be placed atop an Atlas V rocket for its first crewed launch.

United Launch Alliance

NASA is planning to significantly delay the launch of the Crew 9 mission to the International Space Station due to ongoing concerns about the Starliner spacecraft currently attached to the station.

While the space agency has not said anything publicly, sources say NASA should announce the decision this week. Officials are contemplating moving the Crew-9 mission from its current date of August 18 to September 24, a significant slip.

Nominally, this Crew Dragon mission will carry NASA astronauts Zena Cardman, spacecraft commander; Nick Hague, pilot; and Stephanie Wilson, mission specialist; as well as Roscosmos cosmonaut Alexander Gorbunov, for a six-month journey to the space station. However, NASA has been considering alternatives to the crew lineup—possibly launching with two astronauts instead of four—due to ongoing discussions about the viability of Starliner to safely return astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams to Earth.

As of late last week, NASA still had not decided whether the Starliner vehicle, which is built and operated by Boeing, should be used to fly its two crew members home. During its launch and ascent to the space station two months ago, five small thrusters on the Starliner spacecraft failed. After extensive ground testing of the thrusters, as well as some brief in-space firings, NASA had planned to make a decision last week on whether to return Starliner with crew. However, a Flight Readiness Review planned for last Thursday was delayed after internal disagreements at NASA about the safety of Starliner.

At issue is the performance of the small reaction control system thrusters in proximity to the space station. If the right combination of them fail before Starliner has moved sufficiently far from the station, Starliner could become uncontrollable and collide with the space station. The thrusters are also needed later in the flight back to Earth to set up the critical de-orbit burn and entry in Earth’s atmosphere.

Software struggles

NASA has quietly been studying the possibility of crew returning in a Dragon for more than a month. As NASA and Boeing engineers have yet to identify a root cause of the thruster failure, the possibility of Wilmore and Williams returning on a Dragon spacecraft has increased in the last 10 days. NASA has consistently said that ‘crew safety’ will be its No. 1 priority in deciding how to proceed.

The Crew 9 delay is relevant to the Starliner dilemma for a couple of reasons. One, it gives NASA more time to determine the flight-worthiness of Starliner. However, there is also another surprising reason for the delay—the need to update Starliner’s flight software. Three separate, well-placed sources have confirmed to Ars that the current flight software on board Starliner cannot perform an automated undocking from the space station and entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

At first blush, this seems absurd. After all, Boeing’s Orbital Flight Test 2 mission in May 2022 was a fully automated test of the Starliner vehicle. During this mission, the spacecraft flew up to the space station without crew on board and then returned to Earth six days later. Although the 2022 flight test was completed by a different Starliner vehicle, it clearly demonstrated the ability of the program’s flight software to autonomously dock and return to Earth. Boeing did not respond to a media query about why this capability was removed for the crew flight test.

NASA likely to significantly delay the launch of Crew 9 due to Starliner issues Read More »