This time around, we cover the Hanson/Alexander debates on the value of medicine, and otherwise we mostly have good news.

Regeneron administers a single shot in a genetically deaf child’s ear, and they can hear after a few months, n=2 so far.

Great news: An mRNA vaccine in early human clinical trials reprograms the immune system to attack glioblastoma, the most aggressive and lethal brain tumor. It will now proceed to Phase I. In a saner world, people would be able to try this now.

More great news, we have a cancer vaccine trial in the UK.

And we’re testing personalized mRNA BioNTech canner vaccines too.

US paying Moderna $176 million to develop a pandemic vaccine against bird flu.

We also have this claim that Lorlatinib jumps cancer PFS rates from 8% to 60%.

Early results from a study show the GLP-1 drug liraglutide could reduce cravings in people with opioid use disorder by 40% compared with a placebo. This seems like a clear case where no reasonable person would wait for more than we already have? If there was someone I cared about who had an opioid problem I would do what it took to get them on a GLP-1 drug.

Rumblings that GLP-1 drugs might improve fertility?

Rumblings that GLP-1 drugs could reduce heart attack, stroke and death even if you don’t lose weight, according to a new analysis? Survey says 6% of Americans might already be on them. Weight loss in studies continues for more than a year in a majority of patients, sustained up to four years, which is what they studied so far.

The case that GLP-1s can be sued against all addictions at scale. It gives users a sense of control which reduces addictive behaviors across the board, including acting as a ‘vaccine’ against developing new addictions. It can be additive to existing treatments. More alcoholics (as an example) already take GLP-1s than existing indicated anti-addiction medications, and a study showed 50%-56% reduction in risk of new or recurring alcohol addictions, another showed 30%-50% reduction for cannabis.

How to cover this? Sigh. I do appreciate the especially clean example below.

Matthew Yglesias: Conservatives more than liberals will see the systematic negativity bias at work in coverage of GLP-agonists.

Less likely to admit that this same dynamic colors everything including coverage of crime and the economy.

The situation is that there is a new drug that is helping people without hurting anyone, so they write an article about how it is increasing ‘health disparities.’

The point is that they are writing similar things for everything else, too.

The Free Press’s Bari Weiss and Johann Hari do a second round of ‘Ozempic good or bad.’ It takes a while for Hari to get to actual potential downsides.

The first is a claimed (but highly disputed) 50%-75% increased risk of thyroid cancer. That’s not great, but clearly overwhelmed by reduced risks elsewhere.

The second is the worry of what else it is doing to your brain. Others have noticed it might be actively great here, giving people more impulse control, helping with things like smoking or gambling. Hari worries it might hurt his motivation for writing or sex. That seems like the kind of thing one can measure, both in general and in yourself. If people were losing motivation to do work, and this hurt productivity, we would know.

The main objection seems to be that obesity is a moral failure of our civilization and ourselves, so it would be wrong to fix it with a pill rather than correct the underlying issues like processed foods and lack of exercise. Why not be like Japan?

To which the most obvious response is that it is way too late for America to take that path. That does not mean that people should suffer. And if we find a way to fix the issues raised by our diets without changing (‘fixing’) our diets, that is great, not a cause for concern.

The other obvious response is: Who cares? The important thing is to fix it.

Believing he is responding to Hanson and Caplan, Scott Alexander makes the case that medicine, and more access to medicine, does indeed improve health, and that claims to the contrary are misunderstood.

Robin Hanson responds here, with lots of quotes, that he never claimed medicine was useless, rather that additional medical spending on the margin appears useless. Cut Medicine in Half, he says, not cut medicine entirely. Then Scott Alexander responded again.

Scott Alexander’s conclusion in his first post was that medicine obviously works, and the argument should be whether it is effective on the margin, or whether marginally more insurance is cost effective. Robin agrees these are the questions, and convincingly says he been asking them whole time.

The question is, are we spending too much on health care, given the costs and benefits? Robin thinks clearly yes. It seems hard to arrive at any other conclusion.

It is a useful exercise to step through Scott’s arguments. What does the case for ‘medicine does something rather than nothing’ look like?

-

Scott’s first argument is that modern medicine improves survival rates from diseases. In particular that five-year survival rates from cancer are greatly improved. The problem is that health care also greatly increases diagnosis of cancer, and the marginal diagnoses are mild cases. The same potentially applies for other conditions he mentions.

-

I understand the desire to control for outside conditions, but you do have to pick your poison. And the need to control for outside conditions points to those conditions having at least a large share of the effects. The story of cancer rates is largely the story of smoking rates.

-

Robin responds also: But [Scott] seems well aware that many other specialists judge differently here [versus Scott’s judgment that being healthier is only at most 20%-50% of the effect.]

-

Scott next tackles the RAND health insurance experiment, with people getting various qualities of health coverage. He says that RAND actually found a big effect for men ‘at elevated risk’ on hypertension, that this would mean a 1.1% increased 5-year survival rate at age 50 (as in, by age 55, out of 1,000 such men, the treatment would keep an extra 11 of them alive). And yes, glasses fix vision, we agree. Scott defends the failure to accomplish anything else measured. Okay.

-

The mortality claim is based on the blood pressure impact. So it is assuming that changing blood pressure via treatment changes mortality. I would not assume that this is true.

-

This does not contradict Hanson’s position, which I understand to be: ‘medicine is in some ways helpful and in some ways harmful and if you exclude a few highlights like trauma care where we are confident it is helpful, the rest mostly cancels out.’

-

If there was a large overall mortality effect (in any of these studies) I presume we would know, but Scott says the samples weren’t large enough for that.

-

Note that this also is evidence for ‘doctor lectures do not effectively persuade people to quit smoking, lose weight or change their diets.’

-

Scott gets to the famous Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. People randomly got Medicaid or didn’t, those that did then used more health care. Were the mental improvements from this primarily a placebo plus an income effect, especially since a lot of it happened right away before any treatments? Were there physical effects?

-

Once again Scott is focusing on ‘gave people with hypertension medication to lower blood pressure’ as his example of medicine working, which he essentially asserts based on the knowledge that the medication does this. He is saying that the medication works because we know the medication works, and the treatment group got more of the medication, so medicine works. Which does not seem like it meaningfully answers the claims.

-

Scott argues that the study lacked power to pick up on the physical impacts of medicine. This seems like a stronger rebuttal, at least to individual null results like the hypertension effect.

-

Scott next goes to the Karnataka Health Insurance Experiment in India.

-

He basically dismisses this one as having too little power, because the people who got insurance did not know what it was and did not consume much care.

-

This seems like a reasonable take here when looking for smaller effects. But Robin points out that there was substantial utilization change, and relatively large changes can be ruled out, although for smaller ones the likelihood ratio here is not so large.

-

Putting it all together, Scott claims that the studies mostly are vastly underpowered, except the Oregon self-reported impacts which he admits could be (a still effective, it counts) placebo.

-

Scott then points to other more recent studies he says are more positive.

-

We do get an all-cause mortality impact, Goldin, Lurie, and McCubbin claim 56-64 year-olds had one fewer death per 1,648 individuals who got a letter to get insurance, over the following two years, p = 0.01. They were 1.1% more likely to buy insurance. They go back and forth on this one a lot, link includes responses by Dr. Goldin. I think the Lindley’s Paradox argument here is actually pretty strong and Dr. Goldin’s response to it is weak, despite Scott thinking it looks strong – you have to focus on likelihood ratios.

-

But this effect is completely physically impossible if you attribute it to people buying insurance, because it would be larger than the size of the total death rate, and presumably no one thinks medicine is that good. Perhaps this explains why Robin dismisses this as noise.

-

Robin has different calculations, but he also comes up with absurd answers that imply ludicrous amounts of impact on all-cause mortality.

-

Then there are three more studies. States expanding Medicaid had lower mortality, as did Massachusetts after the similar Romneycare, and Medicaid availability lowered child mortality. Low p-values.

-

I basically buy that there is an all-cause mortality effect here, but how do we differentiate the stories here? Story one is that medicine mostly works. Story two is that trauma care, vaccines, antibiotics and a handful of other things clearly work, and the rest is a mixed bag that mostly cancels out. We also need to worry about wealth effects.

I agree with Scott that there is a clear distinction between ‘core care’ and ‘extra care.’ It is not a boolean, but we all know those times that no really, we need to go to the doctor, which in turn splits into ‘I need to see a doctor’ versus ‘no really I might die if I don’t see a doctor,’ versus those times we might want to go.

In Scott’s follow-up post, he sees Hanson as being unable to decide whether or not we can tell which parts of medicine work, sees Hanson being far too willing to cut essentially at random, and proposes a trilemma.

-

If we can’t distinguish good and bad medical interventions, we shouldn’t cut medicine, because medicine is net positive now.

-

Or if we can’t distinguish, but the average intervention is net negative if you include costs, you should cut everything.

-

Or if we can distinguish, then we should… pay a lot of attention to getting that right?

Before reading Hanson’s reply, here would be my response:

-

There are some things we know work or have high confidence work, in ways that have very good cost-benefit.

-

There are then a lot of other things, where we don’t know how much or if they work, or whether they are worth it. And also some where we actually know they aren’t worth it or don’t work, but we’re currently stuck with them.

-

If we were forced to cut medicine by half, no we would not do that by only treating half of trauma patients and only giving half of people antibiotics. People would make reasonably good decisions.

-

When Robin Hanson says trying to figure out what treatments work so we cut only the things that don’t work is a ‘monkey trap,’ what he means is that you say cut medicine by half, they say they will appoint a committee to do a study to figure out how to figure out which ones don’t work, there are a bunch of big endless fights and accusations and a lot of lobbying and you don’t cut anything.

-

Scott wants to argue about cutting entire categories of care. Does cancer care work? If so, don’t cut it. But I would hope we all agree that at current knowledge levels the right amount of cancer care is more than zero and less than what we do now, at least for those Americans with good insurance. If we cut cancer care costs by half the doctors would mostly do a rather good job identifying which half to keep.

-

We can largely do this by shifting more of the costs for marginal care onto the patients. They will mostly make reasonable decisions on which things to keep.

-

And come on, we all basically know all this.

Also, to nitpick a bit because of who is writing this, when Scott uses the example of asking whether guns kill people, and how you might study this by giving people vouchers to buy guns and seeing if they get convicted of murder more people than a control group, I notice this seems terrible even if you ignore the ethical problems. This is so obviously a no good, very bad, terrible way to test the question of ‘does shooting someone with a gun kill them?’ because this is asking a completely different question. It is not merely about whether the impact is statistically significant or not. Whereas yes, we do seem to have records of how much more money was spent on healthcare in the studies this is supposed to be a metaphor for?

And then Scott basically… says Hanson is wrong about the strength of his evidence but is probably mostly right about the underlying questions?

Scott Alexander: In case my own position isn’t clear: I think lots of medicine is useless, and that most doctors would agree with this. We over-order tests when we don’t need them, we do a lot of ineffective stuff to please patients (starting with antibiotics for viral illnesses, but sometimes going up to surgeries that have only placebo value), and we do lots of treatments that we know fail >90% of the time, like certain kinds of rehab for drug addiction (we tell ourselves we’re doing it because the tiny number of people who do benefit deserve a chance, but a rational health bureaucrat who wants to save money might not see it that way).

Does all this add up to half? I’m not sure. But I think we can work on cutting back on this stuff without saying things like “maybe medicine is just about signaling” or “how do we know if any of it works?” or “you can’t trust clinical trials because they’re all biased”, and that it very very much matters which parts of medicine we cut.

(something like this has to be true, because eg Britain spends only half as much per person as the US on healthcare, and Brits have approximately as good health outcomes. This isn’t because medicine, in the sense of specific treatments for specific diseases, works any better or worse in Britain – it’s for the same reasons that colleges have ballooned in cost without educating people much better.)

It wouldn’t surprise me if expensive insurance doesn’t have much marginal mortality benefit over cheap insurance, although it might still be worth it on a personal level (because it gets you faster care, kinder doctors, fancier hospital rooms, etc).

So yes, our spending double what the UK spends on medicine is probably buying us very little additional health or longevity.

Hanson’s second response mostly says ‘I keep saying that we should cut medicine by having people pay out of their own pockets, and you should cut your own consumption by asking if you would have paid the sticker price for it.’ And he proposes or reminds us of other methods of differentiating good versus bad care.

Hanson also emphasizes that a lot of this is paying more for fancier versions of the same treatments, or more expensive treatment options, and you can usually get most or all of the benefits without paying more.

Certainly I have witnessed this, where the cost difference of what different treatment providers bill is rather stunning. Yes, the more expensive is better, but wow is the marginal benefit not worth the marginal cost.

John Mandrola especially endorses Hanson’s advice for finding low-value care.

-

Ask about a treatment’s Cochrane Review rating.

-

Ask if a treatment is done in low spending geographic regions.

-

Ask if treatments are done in small hospitals.

-

Ask your doctor how strongly they recommend a particular treatment; decline if recommendation is weak. (I’ve done this.)

-

Ask yourself and associates if you would be willing to pay for them out of your own pocket, if insurance did not cover them.

I agree that these recommendations seem excellent, in cases where you are unsure. Scott Alexander thinks they are pretty good too. And again I would emphasize that your instincts on this are probably pretty good no matter how you get them.

In the end, it sounds like Robin and Scott (and I) are not that far apart on the actual physical question of what actions cause or don’t cause health outcomes to improve. All three of us mostly agree on the ground truth that America spends a lot of money that is wasted, as the result of signaling and regulatory capture and various toxic dynamics, and we should work to spend a lot less.

The real fight here, I think, is mostly that Robin Hanson wants to or at least is down to lower the status of medicine and doctors, and to make it not a sacred value. Scott Alexander wants to not do that and defend medicine and doctors, and keep medicine sacred.

One way to spend too much on healthcare is to write checks that are the wrong size.

Your periodic reminder that pharmaceutical pricing is crazy town, with rampant price discrimination, and you can and should game the hell out of it.

Alex Tabarrok: The joys of pharmaceutical pricing.

Picking up a Rx at Walmart. I say $150? that seems high. The cashier responds do you have the GoodRx app? I download the free app and sign up while standing in line. New price $8.

Gwern on how much credence to give new causal claims in epidemiology or nutrition, especially claims something is a ‘subtle poison.’ I agree with the conclusion that ignoring such claims entirely unless there is a unique reason is at worst a small mistake, and doing otherwise risks much larger mistakes than that.

The shortage of Adderall is not only flat out sabotage, it is stupider-than-you-could-put-into-a-work-of-fiction level stupid sabotage by the DEA.

Inside Ascent’s 320,000-square-foot factory in Central Islip, a labyrinth of sterile white hallways connects 105 manufacturing rooms, some of them containing large, intricate machines capable of producing 400,000 tablets per hour. In one of these rooms, Ascent’s founder and CEO — Sudhakar Vidiyala, Meghana’s father — points to a hulking unit that he says is worth $1.5 million. It’s used to produce time-release Concerta tablets with three colored layers, each dispensing the drug’s active ingredient at a different point in the tablet’s journey through the body. “About 25 percent of the generic market would pass through this machine,” he says. “But we didn’t make a single pill in 2023.”

… the company has acknowledged that it committed infractions. For example, orders struck from 222s must be crossed out with a line and the word cancel written next to them. Investigators found two instances in which Ascent employees had drawn the line but failed to write the word.

So for that style of failure, they shut down the entire factory.

We need to take this authority away from the DEA. The DEA should deal with illegal drugs and only illegal drugs. Regulation of legal drugs should for now go to the FDA. Of course, FDA Delenda Est for other reasons, but you do what you can.

The FDA often gets in the way. It would be easy to think that the FDA’s failures would be illustrated by the rejection of MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder.

In some ways, it was. The logic on the rejection was in part that you should keep your intervention safe in the lab until it is perfect, and until then ban it, rather than allowing learning and iteration and helping people. And that’s really dumb.

They also objected that the studies were effectively unblinded (because if you take MDMA you would know) and some people had previously taken MDMA. To which we all reply, it’s MDMA, what would you have the experimenters do? What is your proposed active placebo here? I don’t think this is avoidable.

The FDA also said they did not sufficiently study ‘the known cardiovascular effects,’ wait aren’t they known? To be fair to the FDA they raised these crazy objections in advance and Lykos proceeded with the study without listening, which is kind of (also) on them at that point. The study did not do its job, which was to follow FDA instructions.

But also it turns out the study was horrible in other ways. Not merely horrible ‘they didn’t follow the instructed procedure’ type of ways, although there was that too. Horrible in the ‘experimenters asked patients to give higher ratings to help get the drug approved’ and ‘experimenters having sex with the patients while the patients were high’ kinds of ways.

Yeah, well, whoops.

Doing a study on MDMA is hard. Blinding it is almost impossible. The FDA is not inclined to help you. That does not excuse falling down on the job.

The FDA is considering black octagon warning labels on the front of packages of foods to warn of things like ‘excess’ fat, sodium, sugar or calories. So judgemental.

The first thing I notice is these labels are less obnoxious than I expected, but they are still ugly, and rather large on small items. The second is that if you are going to do this, you would want better differentiation between the different warnings. Shouldn’t they be different colors or shapes or something? The whole point is to make it easy.

I am very much in favor of the existing nutrition labels, which are highly informative. I would be in favor of extending them a bit to make them easier to quickly scan for the things people most care about. My initial reaction is that this new proposal is obnoxious, and it goes too far in telling people what they should care about and putting it constantly in their face. However, in Chile, they say that sugar consumption dropped 10% after the labels were used. That is a big win, if people are responding to superior information rather than having their preferences overridden. So if we gather the data and see that the shift is voluntary and this large, then I can see it.

How about instead the FDA do what should be its job, and offer reciprocity with sister agencies like the European Medicines Agency or at least fast tracking for things those agencies have approved. The example here is there is a drug called ambroxol that helps with coughs and colds, in wide use since 1979, and in America you can’t have it.

An example of FDA trying to do its job: They are including more regulatory feedback earlier in the clinical trial process, based on lessons from Operation Warp Speed.

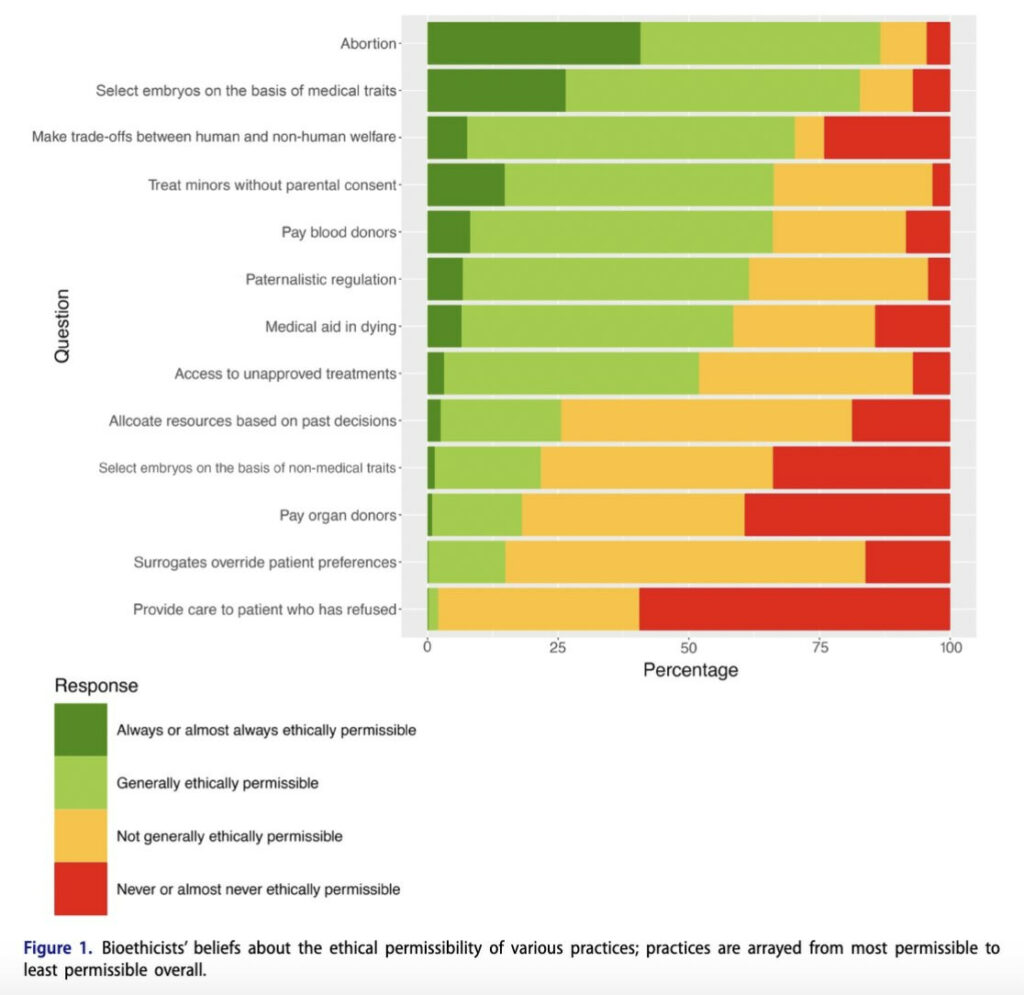

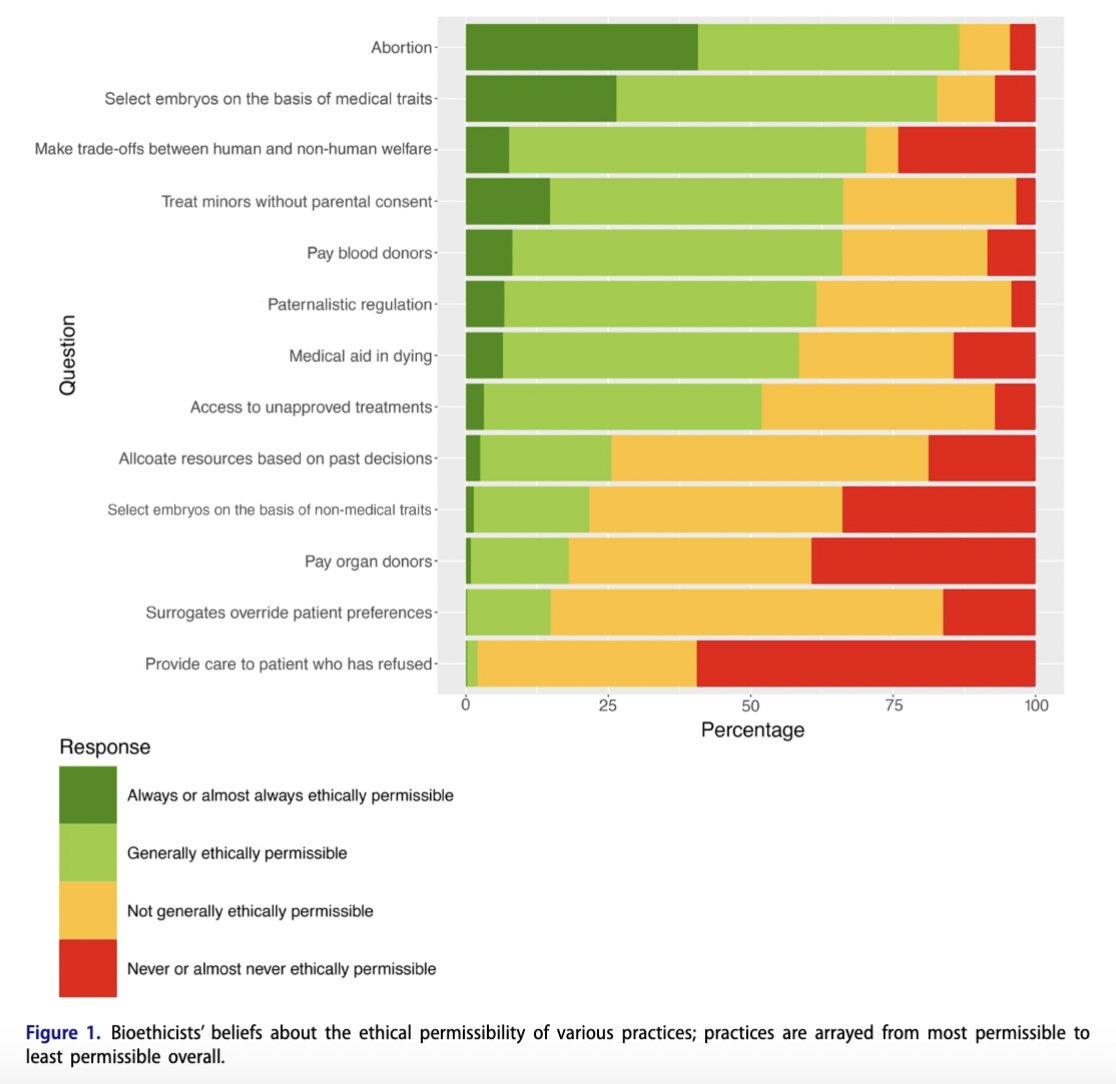

How terrible are bioethicists anyway, by their own admission?

Bryan Caplan: Someone smart told me bioethicists weren’t so bad, and actually supported Human Challenge Trials.

But I’m sticking with my adage that “Bioethics is to ethics as astrology is to astronomy.”

Leah Pierson: Our article ($53?!), Bioethicists Today: Results of the Views in Bioethics Survey (VIBeS), is now out in AJOB! We surveyed 824 US bioethicists on:

-

Major issues in bioethics, like medical aid in dying, paying organ donors, abortion, and many others

-

Their backgrounds

…

There’s consensus on certain issues: For instance, most bioethicists think it’s ethically permissible to:

– Select embryos based on medical traits, but not based on non-medical traits

– Pay blood donors, but not organ donors

…

Bioethicists’ normative commitments also predict their views:

For instance, consequentialist bioethicists are more likely to believe that medical aid in dying is morally permissible (82% of consequentialists vs. 57% of deontologists and 38% of virtue ethicists).

The hidden champion here is ‘allocate resources based on past decisions.’ Do you support the idea that people should be able to enter into and honor agreements, make commitments or own property? Or is all of that old and busted?

It seems ~75% of ‘bioethicists’ think that abiding by agreements because you agreed is not usually ethically permissible. About 20% think it is almost never permissible. It has been pointed out to me that no, what this presumably means is the past decisions of the patients. Except when smokers get first crack at the Covid vaccine. So yeah.

These same people also think abortion is more ethically permissible than choosing embryos on the basis of ‘medical’ traits, and are highly against the idea that you might choose an otherwise better embryo rather than a worse one.

So in conclusion, no, I do not think it is fair to say that bioethicists are to ethics what astrologists are to astronomy. Astrologists do not actively try to damage the sky.

Scott Sumner on the Scott Alexander analysis of Covid origins. He is with Scott Alexander on 90% zoonosis, and says ‘good for me’ and others like me, who have decided not to dive deeply into this issue and retain odds closer to 50/50.

Paper on the cost of mask mandates (paper). Tyler Cowen raises the question of willingness to pay (to be exempt) versus willingness to be paid, which is often much higher. Mostly I believe willingness to pay, and treat willingness to be paid as a paranoid upper bound combined with people hating markets. Also if you ask willingness to pay (or be paid) to be exempt form the mandate, you should also ask the same question about imposing the mandate around you. If the average person was willing to pay $525 to be exempt, how much would they have paid or need to be paid to allow everyone around them to be exempt but not them? Or everyone together?

For a fun look at how deep people can go in the most nonsensical rabbit holes, Jonathan Engler explains that the “covid” narrative is fake and there was no pandemic. I always love true refuge in audacity.

Your periodic reminder that we went fast when we created the Covid vaccines, but could have gone much faster.

Sam D’Amico: The entire discussion around this is still cursed but has anyone done a postmortem on how fast we could have YOLO’d out the mRNA vaccines if we manufactured at risk and skipped the clinical trials.

Josie Zayner: Myself and two other Biohackers created and tested a DNA based COVID vaccine on ourselves before Fall 2020, before any vaccine was available, and we moved slow so we could livestream the whole design and testing process. I was banned for life from YouTube for doing this.

Scott Alexander reviews the book The Others Within Us, about Internal Family Systems and the fact that occasionally it discovers what the book’s author thinks are literal demons. Here Disfigured Praise offers a few additional thoughts. I did experiment a little with IFS once so I have some experience with the baseline case. You are told to go into a form of trance and think you have an amazing core self, and also these other ‘parts’ that are functionally other people inside you, that you created for some purpose, but that are often misaligned. Then you talk to and negotiate with those parts until they agree to stop doing the misaligned things. In this theory, there is (almost) always a path to doing this if you are patient and understanding, whereas hostility doesn’t work.

This is often effective at causing change, for reasons that should be obvious. It is also highly dangerous to ask people to imagine parts of them that are actively interfering, because you can incept that happening. The parallel to multiple personality syndrome is obvious, and Scott points it out. This is not ‘safe’ therapy. But the self being supposedly good and in charge, and there (almost) always being a way to solve any problem, means that if the therapist knows what they are doing this is plausibly a worthwhile thing to do sometimes.

As Scott says, we use the cultural models of the brain we have lying around. It makes sense that one could engineer a version of this that, inside our cultural context, gives you maximum opportunity to do well while minimizing downside risk. I am reasonably confident that a well-iterated, well-taught version of this, implemented with empathy and dedication, would often be a good idea.

That does not mean that what is on offer in any given situation qualifies for those adjectives. In practice, I would stay away from IFS unless I had very high confidence of a high quality therapist, and also a situation with enough upside to roll those dice.

The catch discussed here is that every so often, less than 1% of the time, patients insist one or more of their parts are not part of them, and instead are literal demons. The therapists try really hard to convince the patient that they’re normal parts, and the patients sometimes are having none of it. At which point there is another procedure to get the ‘demon’ to leave on its own or if necessary cast it out.

Which, yeah, of course that is sometimes where a patient’s mind is going to go on this. All the descriptions make perfect sense. And it makes sense to meet those patients where they are, with a procedure that tells them the demons are pretty easy to cast out via an hour of talking in a chair and doing guided imagery. Great response. It sounds like it often does great work, you give the patient the opportunity to decide something awful is distinct from them and give them a way to get rid of it. No latin or levitation or hostility required. Love it.

The problem is that author Robert Falconer rejects this very obvious explanation, instead saying yep, the demons must be literal demons. Whoops. And as Scott notes, if your group starts actually believing in literal demons, you start getting iatrogenic demons, which does not sound like a great thing to be conjuring into existence. So if everyone involved can’t get on the same page of ‘this is a metaphor that you never encourage or bring up first but that you sometimes encounter and here’s how to deal with it’ maybe forget the whole thing.

Mental health problems are only somewhat correlated between generations.

We estimate health associations across generations and dynasties using information on healthcare visits from administrative data for the entire Norwegian population. A parental mental health diagnosis is associated with a 9.3 percentage point (40%) higher probability of a mental health diagnosis of their adolescent child. Intensive margin physical and mental health associations are similar, and dynastic estimates account for about 40% of the intergenerational persistence. We also show that a policy targeting additional health resources for the young children of adults diagnosed with mental health conditions reduced the parent-child mental health association by about 40%.

I am surprised this is so low, since it is the combination of three correlations:

-

Genetic

-

Cultural and Behavioral Patterns

-

Diagnosis

Whereas this is only a 40% difference: 15.5% versus 24.8%, after combining all three. A concentration of extra resources reducing the correlation does not tell us if this concentration is efficient, nor does it tell us the composition of the causes involved, given the diagnosis concern (including treatment’s impact on diagnosis) we cannot even measure how much actual mental illness is being prevented by shifting resources around. So it feels like a deeply wrong question.

My first move would be to attempt a study that tried to control for diagnosis, by using objective measures, ideally including new evaluations. Then try to control for genetic factors using the usual twin study and adaption paper techniques.