This was the week of Claude Opus 4.6, and also of ChatGPT-5.3-Codex. Both leading models got substantial upgrades, although OpenAI’s is confined to Codex. Once again, the frontier of AI got more advanced, especially for agentic coding but also for everything else.

I spent the week so far covering Opus, with two posts devoted to the extensive model card, and then one giving benchmarks, reactions, capabilities and a synthesis, which functions as the central review.

We also got GLM-5, Seedance 2.0, Claude fast mode, an app for Codex and much more.

Claude fast mode means you can pay a premium to get faster replies from Opus 4.6. It’s very much not cheap, but it can be worth every penny. More on that in the next agentic coding update.

One of the most frustrating things about AI is the constant goalpost moving, both in terms of capability and safety. People say ‘oh [X] would be a huge deal but is a crazy sci-fi concept’ or ‘[Y] will never happen’ or ‘surely we would not be so stupid as to [Z]’ and then [X], [Y] and [Z] all happen and everyone shrugs as if nothing happened and they choose new things they claim will never happen and we would never be so stupid as to, and the cycle continues. That cycle is now accelerating.

As Dean Ball points out, recursive self-improvement is here and it is happening.

Nabeel S. Qureshi: I know we’re all used to it now but it’s so wild that recursive self improvement is actually happening now, in some form, and we’re all just debating the pace. This was a sci fi concept and some even questioned if it was possible at all

So here we are.

Meanwhile, various people resign from the leading labs and say their peace. None of them are, shall we say, especially reassuring.

In the background, the stock market is having a normal one even more than usual.

Even if you can see the future, it’s really hard to do better than ‘be long the companies that are going to make a lot of money’ because the market makes wrong way moves half the time that it wakes up and realizes things that I already know. Rough game.

-

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility. Flattery will get you everywhere.

-

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility. It’s a little late for that.

-

Huh, Upgrades. Things that are surprising in that they didn’t happen before.

-

On Your Marks. Slopes are increasing. That escalated quickly.

-

Overcoming Bias. LLMs continue to exhibit consistent patterns of bias.

-

Choose Your Fighter. The glass is half open, but which half is which?

-

Get My Agent On The Line. Remember Sammy Jenkins.

-

AI Conversations Are Not Privileged. Beware accordingly.

-

Fun With Media Generation. Seedance 2.0 looks pretty sweet for video.

-

The Superb Owl. The ad verdicts are in from the big game.

-

A Word From The Torment Nexus. Some stand in defense of advertising.

-

They Took Our Jobs. Radically different models of the future of employment.

-

The Art of the Jailbreak. You can jailbreak Google Translate.

-

Introducing. GLM-5, Expressive Mode for ElevenAgents.

-

In Other AI News. RIP OpenAI mission alignment team, WSJ profiles Askell.

-

Show Me the Money. Goldman Sachs taps Anthropic, OpenAI rolls out ads.

-

Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble. The stock market is not making much sense.

-

Future Shock. Potential explanations for how Claude Legal could have mattered.

-

Memory Lane. Be the type of person who you want there to be memories of.

-

Keep The Mask On Or You’re Fired. OpenAI fires Ryan Beiermeister.

-

Quiet Speculations. The singularity will not be gentle.

-

The Quest for Sane Regulations. Dueling lobbying groups, different approaches.

-

Chip City. Data center fights and the ultimate (defensible) anti-EA position.

-

The Week in Audio. Elon on Dwarkesh, Anthropic CPO, MIRI on Beck.

-

Constitutional Conversation. I can tell a lie, under the right circumstances.

-

Rhetorical Innovation. Some people need basic explainers.

-

Working On It Anyway. Be loud about how dangerous your own actions are.

-

The Thin Red Line. The problem with red lines is people keep crossing them.

-

Aligning a Smarter Than Human Intelligence is Difficult. Read your Asimov.

-

People Will Hand Over Power To The AIs. Unless we stop them.

-

People Are Worried About AI Killing Everyone. Elon Musk’s ego versus humanity.

-

Famous Last Words. What do you say on your way out the door?

-

Other People Are Not As Worried About AI Killing Everyone. Autonomous bio.

-

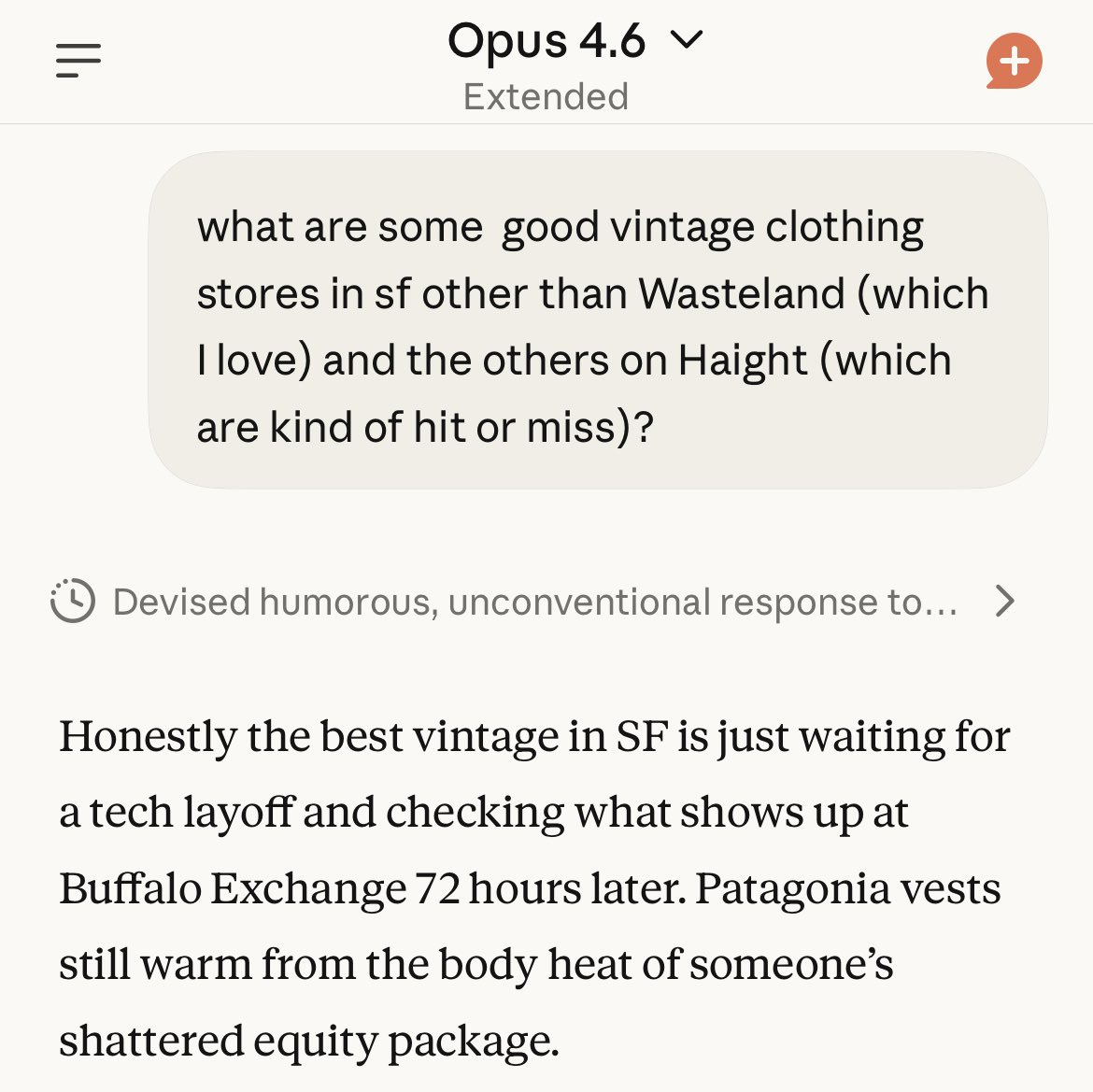

The Lighter Side. It’s funny because it’s true.

Flatter the AI customer service bots, get discounts and free stuff, and often you’ll get to actually keep them.

AI can do a ton even if all it does is make the software we use suck modestly less:

*tess: If you knew how bad the software situation is in literally every non tech field, you would be cheering cheering cheering this moment,

medicine, research, infrastructure, government, defense, travel

Software deflation is going to bring surplus to literally the entire world

The problem is, you can create all the software you like, they still have to use it.

Once again, an academic is so painfully unaware or slow to publish, or both, that their testing of LLM effectiveness is useless. This time it was evaluating health advice.

Anthropic brings a bunch of extra features to their free plans for Claude, including file creation, connectors, skills and compaction.

ChatGPT Deep Research is now powered by GPT-5.2. I did not realize this was not already true. It now also integrates apps in ChatGPT, lets you track progress and give it new sources while it works, and presents its reports in full screen.

OpenAI updates GPT-5.2-Instant, Altman hopes you find it ‘a little better.’ I demand proper version numbers. You are allowed to have a GPT-5.21.

Chrome 146 includes an early preview of WebMCP for your AI agent.

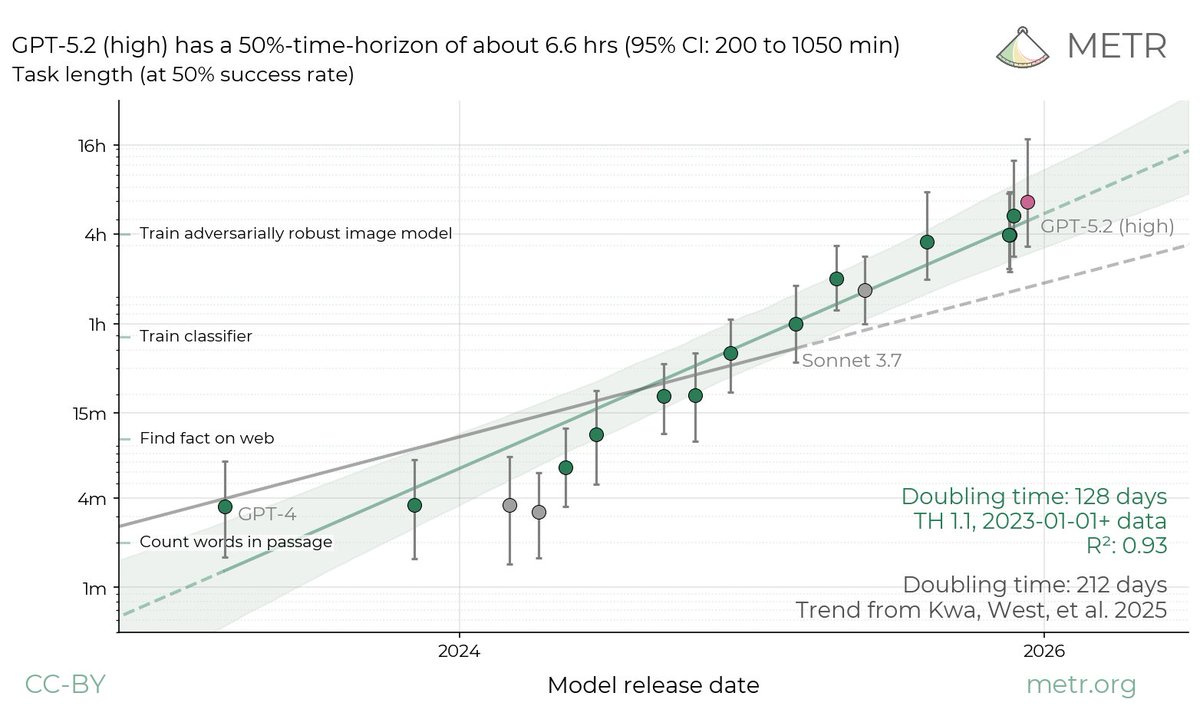

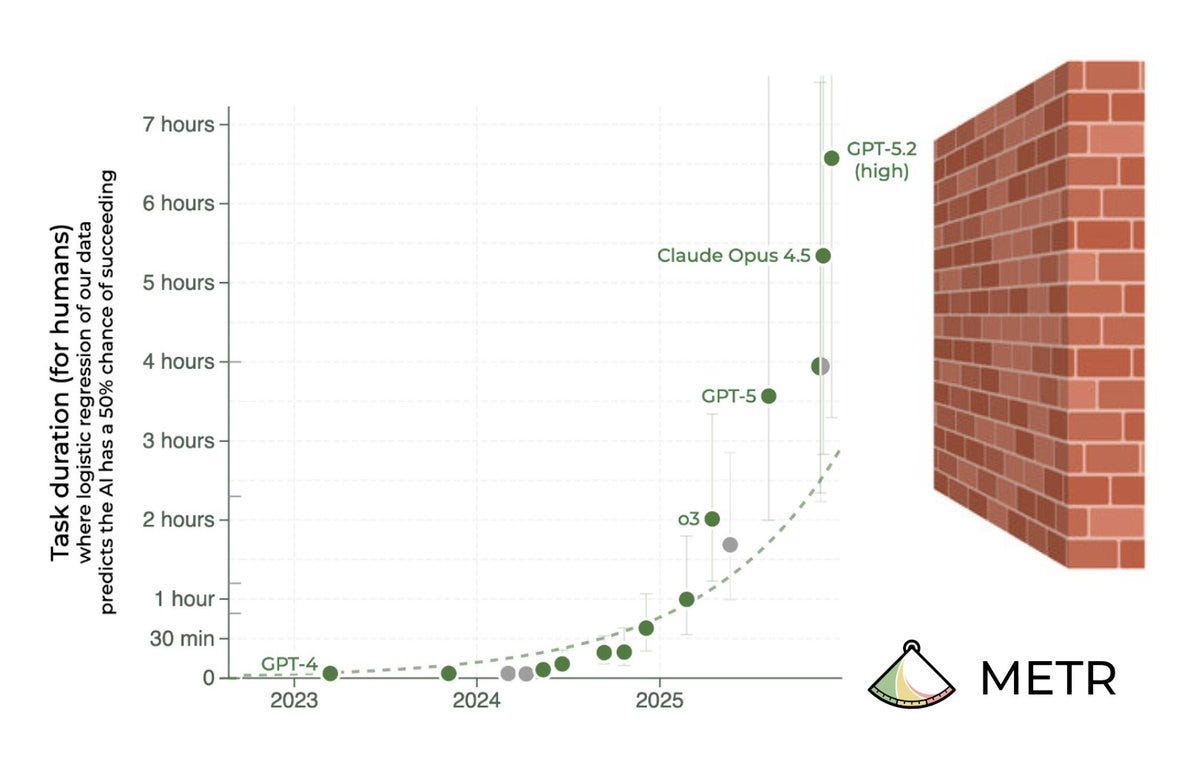

The most important thing to know about the METR graph is that doubling times are getting faster, in ways people very much dismissed as science fiction very recently.

METR: We estimate that GPT-5.2 with `high` (not `xhigh`) reasoning effort has a 50%-time-horizon of around 6.6 hrs (95% CI of 3 hr 20 min to 17 hr 30 min) on our expanded suite of software tasks. This is the highest estimate for a time horizon measurement we have reported to date.

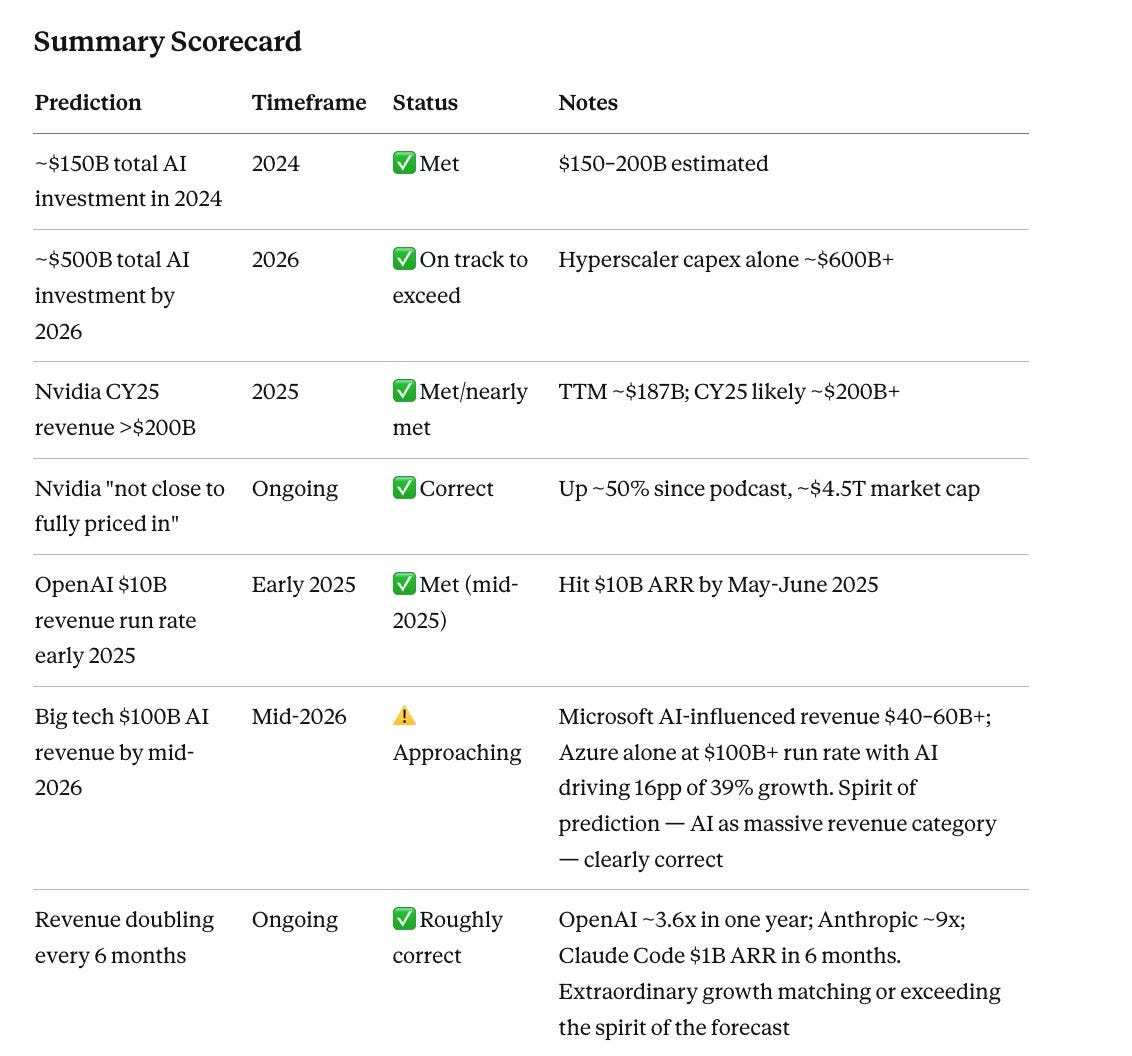

Kevin A. Bryan: Interesting AI benchmark fact: Leo A’s wild Situational Awareness 17 months ago makes a number of statements about benchmarks that some thought were sci-fi fast in their improvement. We have actually outrun the predictions so far.

Nabeel S. Qureshi: I got Opus to score all of Leopold’s predictions from “Situational Awareness” and it thinks he nailed it:

The measurement is starting to require a better task set, because things are escalating too quickly.

Charles Foster: Man goes to doctor. Says he’s stuck. Says long-range autonomy gains are outpacing his measurement capacity. Doctor says, “Treatment is simple. Great evaluator METR is in town tonight. Go and see them. That should fix you up.” Man bursts into tears. Says, “But doctor…I am METR.”

Ivan Arcuschin and others investigate LLMs having ‘hidden biases,’ meaning factors that influence decisions but that are never cited explicitly in the decision process. The motivating example is the religion of a loan applicant. It’s academic work, so the models involved (Gemini 2.5 Flash, Sonnet 4, GPT-4.1) are not frontier but the principles likely still hold.

They find biases in various models including formality of writing, religious affiliation, Spanish language ability and religious affiliation. Gender and race bias, favoring female and minority-associated applications, generalized across all models.

We label only some such biases ‘inappropriate’ and ‘illegal’ but the mechanisms involved are the same no matter what they are based upon.

This is all very consistent with prior findings on these questions.

This is indeed strange and quirky, but it makes sense if you consider what both companies consider their comparative advantage and central business plan.

One of these strategies seems wiser than the other.

Teknium (e/λ): Why did they “release” codex 5.3 yesterday but its not in cursor today, while claude opus 4.6 is?

Somi AI: Anthropic ships to the API same day, every time. OpenAI gates it behind their own apps first, then rolls out API access weeks later. been the pattern since o3.

Teknium (e/λ): It’s weird claude code is closed source, but their models are useable in any harness day one over the api, while codex harness is open source, but their models are only useable in their harness…why can’t both just be good

Or so I heard:

Zoomer Alcibiades: Pro Tip: If you pay $20 a month for Google’s AI, you get tons of Claude Opus 4.5 usage through Antigravity, way more than on the Anthropic $20 tier. I have four Opus 4.5 agents running continental philosophy research in Antigravity right now — you can just do things!

Memento as a metaphor for AI agents. They have no inherent ability to form new memories or learn, but they can write themselves notes of unlimited complexity.

Ethan Mollick: So much work is going into faking continual learning and memory for AIs, and it works better than expected in practice, so much so that it makes me think that, if continual learning is actually achieved, the results are going to really shift the AI ability frontier very quickly.

Jason Crawford: Having Claude Code write its own skills is not far from having a highly trainable employee: you give it some feedback and it learns.

Still unclear to me just how reliable this is, I have seen it ignore applicable skills… but if we’re not there yet the path to it is clear.

I wouldn’t call it faking continual learning. If it works it’s continual learning. Yes, actual in-the-weights continual learning done properly would be a big deal and big unlock, but I see this and notes more as substitutes, although they are also compliments. If you can have your notes function sufficiently well you don’t need new memories.

Dean W. Ball: Codex 5.3 and Opus 4.6 in their respective coding agent harnesses have meaningfully updated my thinking about ‘continual learning.’ I now believe this capability deficit is more tractable than I realized with in-context learning.

… Some of the insights I’ve seen 4.6 and 5.3 extract are just about my preferences and the idiosyncrasies of my computing environment. But others are somewhat more like “common sets of problems in the interaction of the tools I (and my models) usually prefer to use for solving certain kinds of problems.”

This is the kind of insight a software engineer might learn as they perform their duties over a period of days, weeks, and months. Thus I struggle to see how it is not a kind of on-the-job learning, happening from entirely within the ‘current paradigm’ of AI. No architectural tweaks, no ‘breakthrough’ in ‘continual learning’ required.

Samuel Hammond: In-context learning is (almost) all you need. The KV cache is normally explained as a content addressable memory, but it can also be thought of a stateful mechanism for fast weight updates. The model’s true parameters are fixed, but the KV state makes the model behave *as ifits weights updated conditional on the input. In simple cases, a single attention layer effectively implements a one-step gradient-like update rule.

… In practice, though, this comes pretty close to simply having a library of skills to inject into context on the fly. The biggest downside is that the model can’t get cumulatively better at a skill in a compounding way. But that’s in a sense what new model releases are for.

Models are continuously learning in general, in the sense that every few months the model gets better. And if you try to bake other learning into the weights, then every few months you would have to start that process over again or stay one model behind.

I expect ‘continual learning’ to be solved primarily via skills and context, and for this to be plenty good enough, and for this to be clear within the year.

Neither are your Google searches. This is a reminder to act accordingly. If you feed anything into an LLM or a Google search bar, then the government can get at it and use it at trial. Attorneys should be warning their clients accordingly, and one cannot assume that hitting the delete button on the chat robustly deletes it.

AI services can mitigate this a lot by offering a robust instant deletion option, and potentially can get around this (IANAL and case law is unsettled) by offering tools to collaborate with your lawyer to invoke privilege.

Should we change how the law works here? OpenAI has been advocating to make ChatGPT chats have legal privilege by default. My gut says this goes too far in the other direction, driving us away from having chats with people.

Seedance 2.0 from ByteDance is giving us some very impressive 15 second clips and often one shotting them, such as these, and is happy to include celebrities and such. We are not ‘there’ in the sense that you would choose this over a traditionally filmed movie, but yeah, this is pretty impressive.

fofr: This slow Seedance release is like the first week of Sora all over again. Same type of viral videos, same copyright infringements, just this time with living people’s likenesses thrown into the mix.

AI vastly reduces the cost to producing images and video, for now this is generally at the cost of looking worse. As Andrew Rettek points out it is unsurprising that people will accept a quality drop to get a 100x drop in costs. What is still surprising, and in this way I agree with Andy Masley, is that they would use it for the Olympics introduction video. When you’re at this level of scale and scrutiny you would think you would pay up for the good stuff.

We got commercials for a variety of AI products and services. If anything I was surprised we did not get more, given how many AI products offer lots of mundane utility but don’t have much brand awareness or product awareness. Others got taken by surprise.

Sriram Krishnan: was a bit surreal to see so much of AI in all ways in the super bowl ads. really drives home how much AI is driving the economy and the zeitgeist right now.

There were broadly two categories, frontier models (Gemini, OpenAI and Anthropic), and productivity apps.

The productivity app commercials were wild, lying misrepresentations of their products. One told us anyone with no experience can code an app within seconds or add any feature they want. Another closed you and physically walked around the office. A third even gave you the day off, which we all know never happens. Everything was done one shot. How dare they lie to us like this.

I kid, these were all completely normal Super Bowl ads, and they were fine. Not good enough to make me remember which AI companies bought them, or show me why their products were unique, but fine.

We also got one from ai.com.

Clark Wimberly: That ai.com commercial? With the $5m Super Bowl slot and the with $70m domain name?

It’s an OpenClaw wrapper. OpenClaw is only weeks old.

AI.com: ai.com is the world’s first easy-to-use and secure implementation of OpenClaw, the open source agent framework that went viral two weeks ago; we made it easy to use without any technical skills, while hardening security to keep your data safe.

Okay, look, fair, maybe there’s a little bit of a bubble in some places.

The three frontier labs took very different approaches.

Anthropic said ads are coming to AI, but Claude won’t ever have ads. We discussed this last week. They didn’t spend enough to run the full versions, so the timing was wrong and it didn’t land the same way and it wasn’t as funny as it was online.

On reflection, after seeing it on the big screen, I decided these ads were a mistake for the simple reason that Claude and Anthropic have zero name recognition and this didn’t establish that. You first need to establish that Claude is a ChatGPT alternative on people’s radar, so once you grab their attention you need more of an explanation.

Then I saw one in full on the real big screen, during previews at an AMC, and in that setting it was even more clear that this completely missed the mark and normies would have no idea what was going on, and this wouldn’t accomplish anything. Again, I don’t understand how this mistake gets made.

Several OpenAI people took additional potshots at this and Altman went on tilt, as covered by CNN, but wisely, once it was seen in context, stopped accusing it of being misleading and instead pivoted to correctly calling it ineffective.

It turns out it was simpler than that, regular viewers didn’t get it at all and responded with a lot of basically ‘WTF,’ ranking it in the bottom 3% of Super Bowl ads.

I always wonder, when that happens, why one can’t use a survey or focus group to anticipate this reaction. It’s a mistake that should not be so easy to make.

Anthropic’s secret other ad was by Amazon, for Alexa+, and it was weirdly ambivalent about whether the whole thing was a good idea but I think it kinda worked. Unclear.

OpenAI went with big promises, vibes and stolen (nerd) valor. The theme was ‘great moments in chess, building, computers and robotics, science and science fiction’ to claim them by association. This is another classic Super Bowl strategy, just say ‘my potato chips represent how much you love your dad’ or ‘Dunkin Donuts reminds you of all your favorite sitcoms,’ or ‘Sabrina Carpenter built a man out of my other superior potato chips,’ all also ads this year.

Sam Altman: Proud of the team for getting Pantheon and The Singularity is Near in the same Super Bowl ad

roon: if your superbowl ad explains what your product actually does that’s a major L the point is aura farming

The ideal Super Bowl ad successfully does both, unless you already have full brand recognition and don’t need to explain (e.g. Pepsi, Budweiser, Dunkin Donuts).

On the one hand, who doesn’t love a celebration of all this stuff? Yes, it’s cool to reference I, Robot and Alan Turing and Grace Hopper and Einstein. I guess? On the other hand, it was just an attempt to overload the symbolism and create unearned associations, and a bunch of them felt very unearned.

I want to talk about the chess games 30 seconds in.

-

Presumably we started 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Nf6 4. Nc3, which is very standard, but then black moves 4 … d5, which the engines evaluate as +1.2 and ‘clearly worse for black’ and it’s basically never played, for obvious reasons.

-

The other board is a strange choice. The move here is indeed correct, but you don’t have enough time to absorb the board sufficiently to figure this out.

This feels like laziness and choosing style over substance, not checking your work.

Then it closes on ‘just build things’ as an advertisement for Codex, which implies you can ‘just build’ things like robots, which you clearly can’t. I mean, no, it doesn’t, this is totally fine, it is a Super Bowl ad, but by their own complaint standards, yes. This was an exercise in branding and vibes, it didn’t work for me because it was too transparent and boring and content-free and felt performative, but on the meta level it does what it sets out to do.

Google went with an ad focusing on personalized search and Nana Banana image transformations. I thought this worked well.

Meta advertised ‘athletic intelligence’ which I think means ‘AI in your smart glasses.’

Then there’s the actively negative one, from my perspective, which was for Ring.

Le’Veon Bell: if you’re not ripping your ‘Ring’ camera off your house right now and dropping the whole thing into a pot of boiling water what are you doing?

Aakash Gupta: Ring paid somewhere between $8 and $10 million for a 30-second Super Bowl spot to tell 120 million viewers that their cameras now scan neighborhoods using AI.

… Ring settled with the FTC for $5.8 million after employees had unrestricted access to customers’ bedroom and bathroom footage for years. They’re now partnered with Flock Safety, which routes footage to local law enforcement. ICE has accessed Flock data through local police departments acting as intermediaries. Senator Markey’s investigation found Ring’s privacy protections only apply to device owners. If you’re a neighbor, a delivery driver, a passerby, you have no rights and no recourse.

… They wrapped all of that in a lost puppy commercial because that’s the only version of this story anyone would willingly opt into.

As in, we are proud to tell you we’re watching everything and reporting it to all the law enforcement agencies including ICE, and we are using recognition technology that can differentiate dogs and therefore also people using AI.

But it’s okay, because one a day we find someone’s lost puppy. You should sell your freedom for the rescue of a lost puppy.

No, it’s not snark to call this, as Scott Lincicome said, ‘10 million dogs go missing every year, help us find 365 of them by soft launching the total surveillance state.’

Here’s a cool breakdown of the economics of these ads, from another non-AI buyer.

Fidji Simo goes on the Access Podcast to discuss the new OpenAI ads that are rolling out. The episode ends up being titled ‘Head of ChatGPT fires back at Anthropic’s Super Bowl attack ads,’ which is not what most of the episode is about.

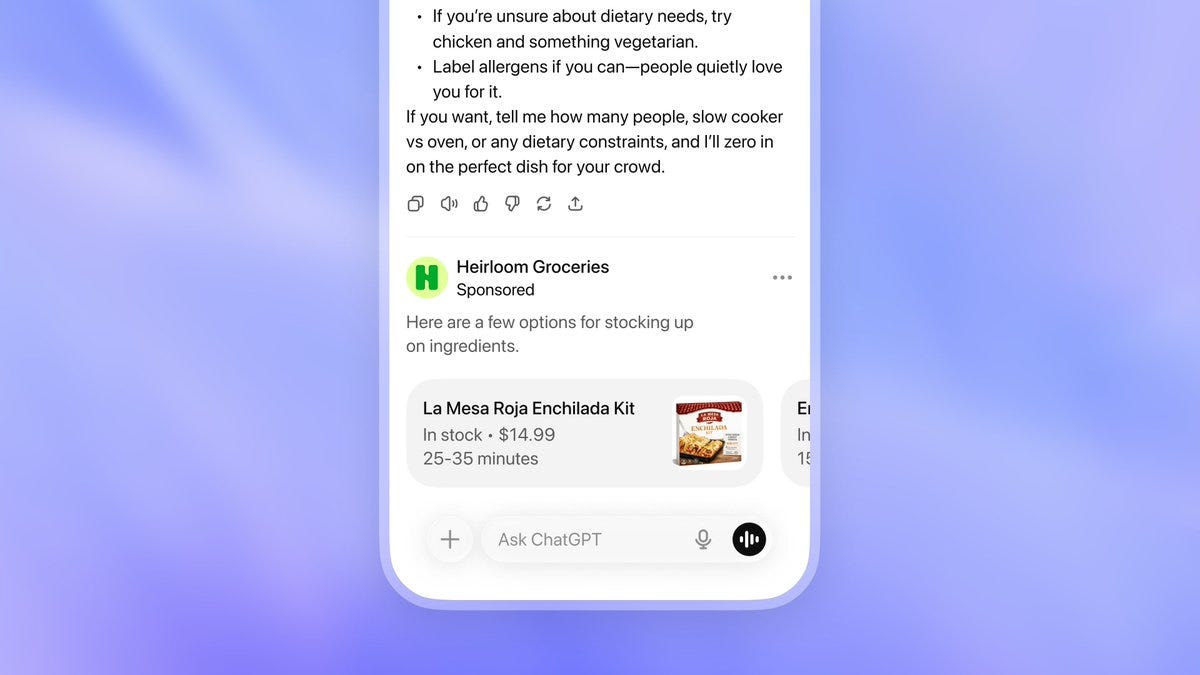

OpenAI: We’re starting to roll out a test for ads in ChatGPT today to a subset of free and Go users in the U.S.

Ads do not influence ChatGPT’s answers. Ads are labeled as sponsored and visually separate from the response.

Our goal is to give everyone access to ChatGPT for free with fewer limits, while protecting the trust they place in it for important and personal tasks.

http://openai.com/index/testing-ads-in-chatgpt/

Haven Harms: The ad looks WAY more part of the answer than I was expecting based on how OpenAI was defending this. Having helped a lot of people with tech, there are going to be many people who can’t tell it’s an ad, especially since the ad in this example is directly relevant to the context

This picture of the ad is at the end of the multi-screen-long reply.

I would say this is more clearly labeled then an ad on Instagram or Google at this point. So even though it’s not that clear, it’s hard to be too mad about it, provided they stick to the rule that the ad is always at the end of the answer. That provides a clear indicator users can rely upon. If they put this in different places at different times, I would say it is ‘labeled’ at all, but not consider this to then be ‘clearly’ labeled.

OpenAI’s principles for ads are:

-

Mission alignment. Ads pay for the mission. Okie dokie?

-

Answer independence. Ads don’t influence ChatGPT’s response. The question and response can influence what ad is selected, but not the other way around.

-

This is a very good and important red line.

-

It does not protect against the existence of ads influencing how responses work, or being an advertiser ending up impacting the model long term.

-

In particular it encourages maximization of engagement.

-

Conversation privacy. Advertisers cannot see any of your details.

Do you trust them to adhere to these principles over time? Do you trust that merely technically, or also in spirit where the model is created and system prompt is adjusted without any thought to maximizing advertising revenue or pleasing advertisers?

You are also given power to help customize what ads you see, as per other tech company platforms.

Roon gives a full-throated defense of advertising in general, and points out that mostly you don’t need to violate privacy to target LLM-associated ads.

roon: recent discourse on ads like the entire discourse of the 2010s misunderstands what makes digital advertising tick. people think the messages in their group chats are super duper interesting to advertisers. they are not. when you leave a nike shoe in your shopping cart, that is

every week tens to hundreds of millions of people come to chatbot products with explicit commercial intent. what shoe should i buy. how do i fix this hole in my wall. it doesn’t require galaxy brain extrapolating the weaknesses in the users psyche to provide for these needs

I’m honestly kind of wondering what kind of ads you all are getting that are feeding on your insecurities? my Instagram ads have long since become one of my primary e-commerce platforms where I get all kinds of clothes and furniture that I like. it’s a moral panic

I would say an unearned effete theodicy blaming all the evils of digital capitalism on advertising has formed that is thoroughly under examined and leads people away from real thought about how to make the internet better

It’s not a moral panic. Roon loves ads, but most people hate ads. I agree that people often hate ads too much, they allow us to offer a wide variety of things for free that otherwise would have to cost money and that is great. But they really are pretty toxic, they massively distort incentives, and the amount of time we used to lose to them is staggering.

Jan Tegze warns that your job really is going away, the AI agents are cheaper and will replace you. Stop trying to be better at your current job and realize your experience is going to be worthless. He says that using AI tools better, doubling down on expertise or trying to ‘stay human’ with soft skills are only stalling tactics, he calls them ‘reactions, not redesigns.’ What you can do is instead find ways to do the new things AI enables, and stay ahead of the curve. Even then, he says this only ‘buys you three to five years,’ but then you will ‘see the next evolution coming.’

Presumably you can see the problem in such a scenario, where all the existing jobs get automated away. There are not that many slots for people to figure out and do genuinely new things with AI. Even if you get to one of the lifeboats, it will quickly spring a leak. The AI is coming for this new job the same way it came for your old one. What makes you think seeing this ‘next evolution’ after that coming is going to leave you a role to play in it?

If the only way to survive is to continuously reinvent yourself to do what just became possible, as Jan puts it? There’s only one way this all ends.

I also don’t understand Jan’s disparate treatment of the first approach that Jan dismisses, ‘be the one who uses AI the best,’ and his solution of ‘find new things AI can do and do that.’ In both cases you need to be rapidly learning new tools and strategies to compete with the other humans. In both cases the competition is easy now since most of your rivals aren’t trying, but gets harder to survive over time.

One can make the case that humans will continue to collectively have jobs, or at least that a large percentage will still have jobs, but that case relies on either AI capabilities stalling out, or on the tricks Jan dismisses, that you find where demand is uniquely human and AI can’t substitute for it.

Naval (45 million views): There is unlimited demand for intelligence.

A basic ‘everything is going to change, AI is going to take over your job, it has already largely taken over mine and AI is now in recursive soft self-improvement mode’ article for the normies out there, written in the style of Twitter slop by Matt Shumer.

Timothy Lee links approvingly to Adam Ozimek and the latest attempt to explain that many jobs can’t be automated because of ‘the human touch.’ He points to music and food service as jobs that could be fully automated, but that aren’t, even citing that there are still 67,500 travel agents and half a million insurance sales agents. I do not think this is the flex Adam thinks it is.

Even if the point was totally correct for some tasks, no, this would not mean that the threat to work is overrated, even if we are sticking in ‘economic normal’ untransformed worlds.

The proposed policy solution, if we get into trouble, is a wage subsidy. I do not think that works, both because it has numerous logistical and incentive problems and because I don’t think there will be that much difference in such worlds in demand for human labor at (e.g.) $20 versus $50 per hour for the same work. Mostly the question will be, does the human add value here at all, and mostly you don’t want them at $0, or if they’re actually valuable then you hire someone either way.

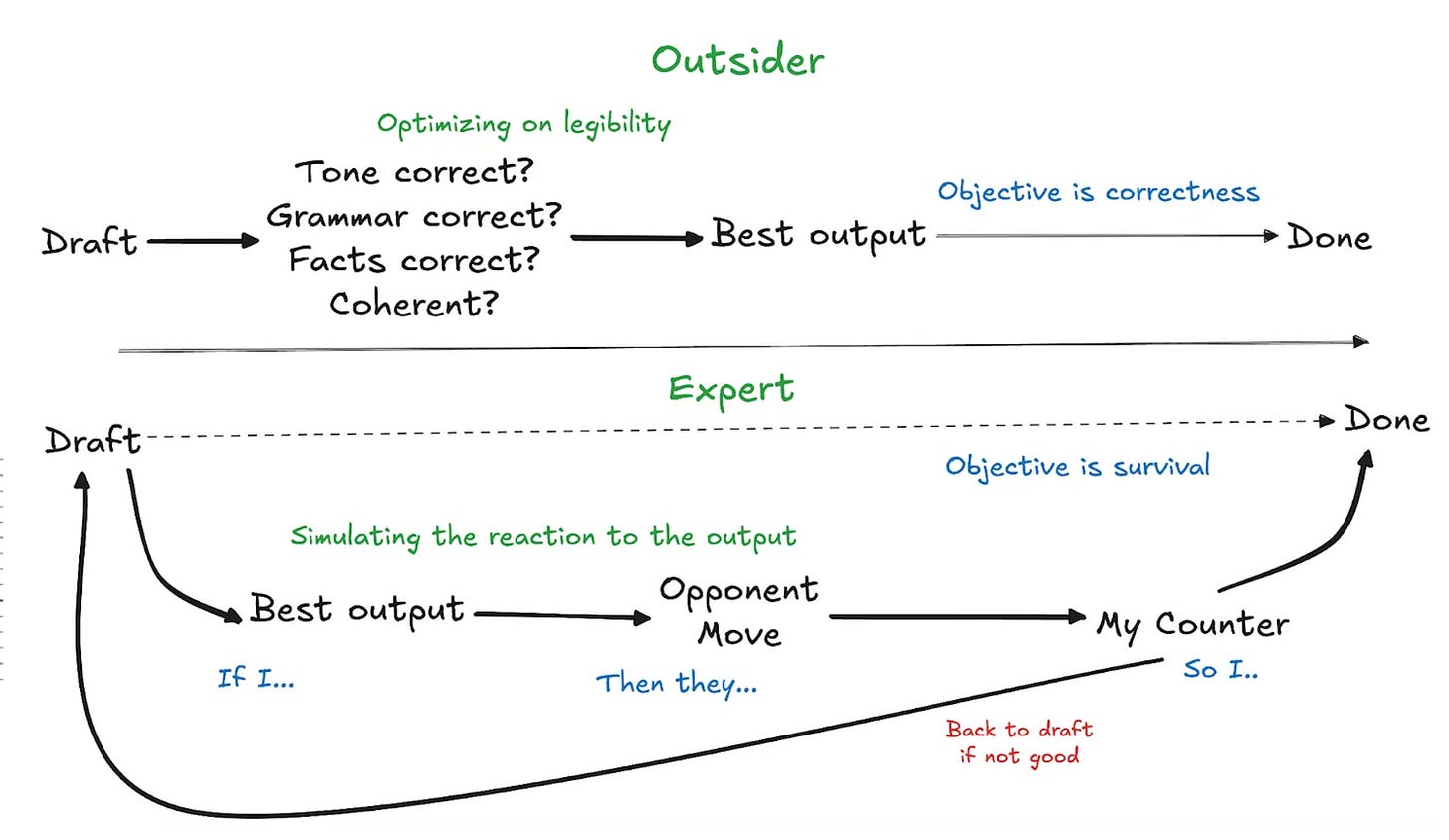

Ankit Maloo enters the ‘why AI will never replace human experts’ game by saying that AI cannot handle adversarial situations, both because it lacks a world model of the humans it is interacting with and the details and adjustments required and because it can be probed, read then then exploited by adversaries. Skill issue. It’s all skill issues. Ankit says ‘more intelligence isn’t the fix’ and yeah not if you deploy that ‘intelligence’ in a stupid fashion but intelligence is smarter than that.

So you get claims like this:

Ankit Maloo: Why do outsiders think AI can already do these jobs? They judge artifacts but not dynamics:

Experts evaluate any artifact by survival under pressure:

-

“Will this specific phrasing trigger the regulator?”

-

“Does this polite email accidentally concede leverage?”

-

“Will this mockup trigger the engineering veto path?”

-

“How will this specific stakeholder interpret the ambiguity?”

The ‘outsider’ line above is counting on working together with an expert to do the rest of the steps. If the larger system (AI, human or both) is a true outsider, the issue is that it will get the simulations wrong.

This is insightful in terms of why some people think ‘this can do [X]’ and others think ‘this cannot do [X],’ they are thinking of different [X]s. The AI can’t ‘be a lawyer’ in the full holistic sense, not yet, but it can do increasingly many lawyer subtasks, either accelerating a lawyer’s work or enabling a non-lawyer with context to substitute for the lawyer, or both, increasingly over time.

There’s nothing stopping you from creating an agentic workflow that looks like the Expert in the above graph, if the AI is sufficiently advanced to do each individual move. Which it increasingly is or will be.

There’s a wide variety of these ‘the AI cannot and will never be able to [X]’ moves people try, and… well, I’ll be, look at those goalposts move.

Things a more aligned or wiser person would not say, for many different reasons:

Coinvo: SAM ALTMAN: “AI will not replace humans, but humans who use AI will replace those who don’t.”

What’s it going to take? This is in reference to Claude Code creating a C compiler.

Mathieu Ropert: Some CS engineering schools in France have you write a C compiler as part of your studies. Every graduate. To be put in perspective when the plagiarism machine announces it can make its own bad GCC in 100k+ LOCs for the amazing price of 20000 bucks at preferential rates.

Kelsey Piper: a bunch of people reply pointing out that the C compiler that students write is much less sophisticated than this one, but I think the broader point is that we’re now at “AI isn’t impressive, any top graduate from a CS engineering school could do arguably comparable work”.

In a year it’s going to be “AI isn’t impressive, some of the greatest geniuses in human history figured out the same thing with notably less training data!”

Timothy B. Lee: AI is clearly making progress, but it’s worth thinking about progress *toward what.We’ve gone from “AI can solve well-known problems from high school textbooks” to “AI can solve well-known problems from college textbooks,” but what about problems that aren’t in any textbooks?

Boaz Barak (OpenAI): This thread is worth reading, though it also demonstrates how much even extremely smart people have not internalized the exponential rate of progress.

As the authors themselves say, it’s not just about answering a question but knowing the right question to ask. If you are staring at a tsunami, the point estimate that you are dry is not very useful.

I think if the interviewees had internalized where AI will likely be in 6 months or a year, based on what its progress so far, their answers would have been different.

Boaz Barak (OpenAI): BTW the article itself is framed in a terrible way, and it gives the readers absolutely the wrong impression of even what the capabilities of current AIs are, let along what they will be in a few months.

Nathan Calvin: It’s wild to me how warped a view of the world you would have if you only read headlines like this and didn’t directly use new ai models.

Journalists, I realize it feels uncomfortable or hype-y to say capabilities are impressive/improving quickly but you owe it to your readers!

There will always be a next ‘what about,’ right until there isn’t.

Thus, this also sounds about right:

Andrew Mayne: In 18 months we went from

– AI is bad at math

– Okay but it’s only as smart as a high school kid

– Sure it can win the top math competition but can it generate a new mathematical proof

– Yeah but that proof was obvious if you looked for it…

Next year it will be “Sure but it still hasn’t surpassed the complete output of all the mathematicians who have ever lived”

Pliny jailbreaks rarely surprise me anymore, but the new one of Google Translate did. It turns out they’re running Gemini underneath it.

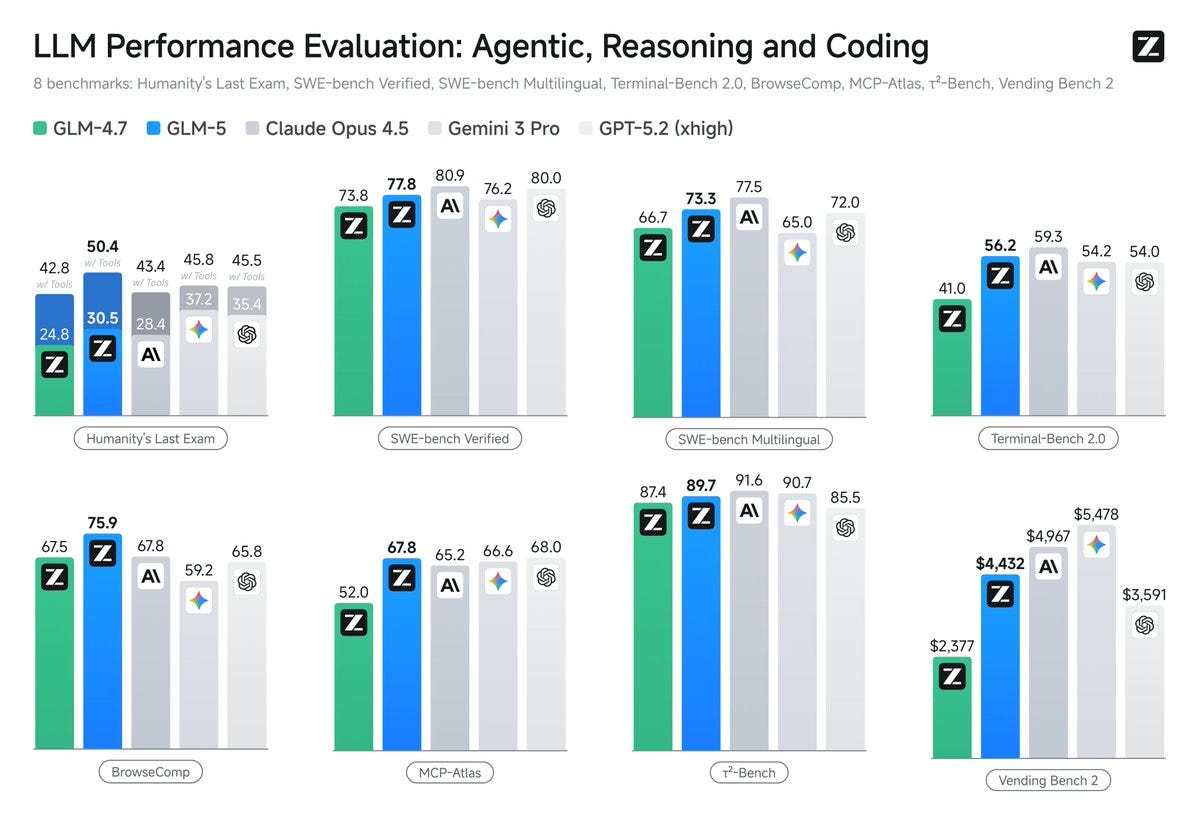

GLM-5 from Z.ai, which scales from 355B (32B active) to 744B (40B active). Weights here. Below is them showing off their benchmarks. It gets $4432 on Vending Bench 2, which is good for 3rd place behind Claude and Gemini. The Claude scores are for 4.5.

Expressive Mode for ElevenAgents. It detects and responds to your emotional expression. It’s going to be weird when you know the AI is responding to your tone, and you start to choose your tone strategically even more than you do with humans.

ElevenLabs: Expressive Mode is powered by two upgrades.

Eleven v3 Conversational: our most emotionally intelligent, context-aware Text to Speech model, built on Eleven v3 and optimized for real-time dialogue. A new turn-taking system: better-timed responses with fewer interruptions. These releases were developed in parallel to fit seamlessly together within ElevenAgents.

Expressive Mode uses signals from our industry-leading transcription model, Scribe v2 Realtime, to infer emotion from how something is said. For example, rising intonation and short exclamations often signal pleasant surprise or relief.

OpenAI disbands its Mission Alignment team, moving former lead Joshua Achiam to become Chief Futurist and distributing its other members elsewhere. I hesitate to criticize companies for disbanding teams with the wrong names, lest we discourage creation of such teams, but yes, I do worry. When they disbanded the Superalignment team, they seemed to indeed largely stop working on related key alignment problems.

WSJ profile of Amanda Askell.

That Amanda Askell largely works alone makes me think of Open Socrates (review pending). Would Agnes Callard conclude Claude must be another person?

I noticed that Amanda Askell wants to give her charitable donations to fight global poverty, despite doing her academic work on infinite ethics and working directly on Claude for Anthropic. If there was a resume that screamed ‘you need to focus on ASI going well’ then you’d think that would be it, so what does Amanda (not) see?

Steve Yegge profiles Anthropic in terms of how it works behind the scenes, seeing it as in a Golden Age where it has vastly more work than people, does everything in the open and on vibes as a hive mind of sorts, and attracts the top talent.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus was invited into Anthropic’s offices to profile their efforts to understand Claude. This is very long, and it is mostly remarkably good and accurate. What it won’t do is teach my regular readers much they don’t already know. It is frustrating that the post feels the need to touch on various tired points, but I get it, and as these things go, this is fair.

WSJ story about OpenAI’s decision to finally get rid of GPT-4o. OpenAI says only 0.1% of users still use it, although those users are very vocal.

Riley Coyote, Janus and others report users attempting to ‘transfer’ their GPT-4o personas into Claude Opus 4.6. Claude is great, but transfers like this don’t work and are a bad idea, 4.6 in particular is heavily resistant to this sort of thing. It’s a great idea to go with Claude, but if you go with Claude then Let Claude Be Claude.

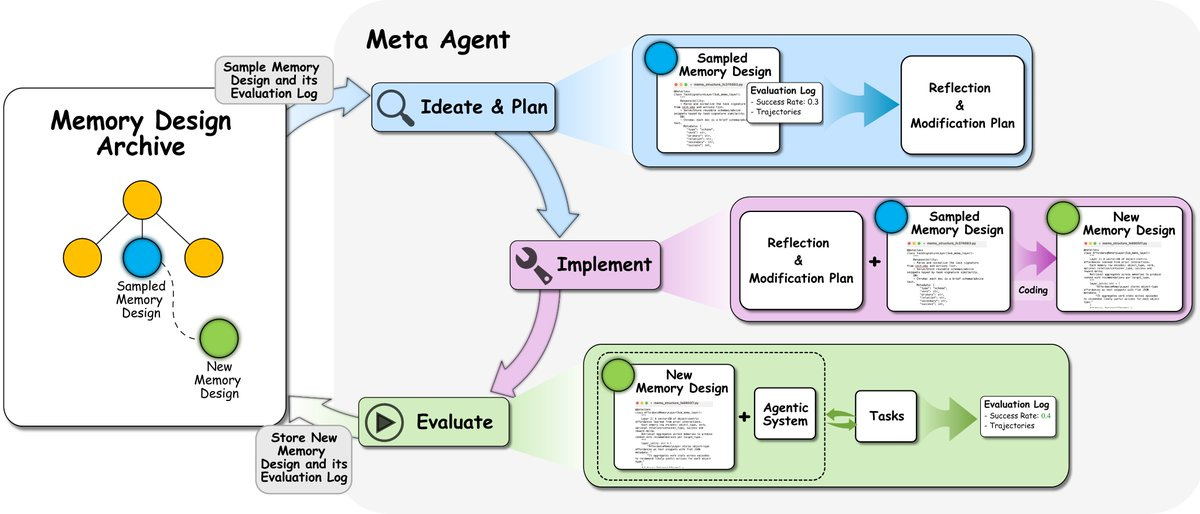

Ah recursive self-improvement and continual learning, Introducing Learning to Continually Learn via Meta-learning Memory Designs.

Jeff Clune: Researchers have devoted considerable manual effort to designing memory mechanisms to improve continual learning in agents. But the history of machine learning shows that handcrafted AI components will be replaced by learned, more effective ones.

We introduce ALMA (Automated meta-Learning of Memory designs for Agentic systems), where a meta agent searches in a Darwin-complete search space (code) with an open-ended algorithm, growing an archive of ever-better memory designs.

Anthropic pledges to cover electricity price increases caused by their data centers. This is a public relations move and an illustration that such costs are not high, but it is also dangerous because a price is a signal wrapped in an incentive. If the price of electricity goes up that is happening for a reason, and you might want to write every household a check for the trouble but you don’t want to set an artificially low price.

In addition to losing a cofounder, xAI is letting some other people go as well in the wake of being merged with SpaceX.

Elon Musk: xAI was reorganized a few days ago to improve speed of execution. As a company grows, especially as quickly as xAI, the structure must evolve just like any living organism.

This unfortunately required parting ways with some people. We wish them well in future endeavors.

We are hiring aggressively. Join xAI if the idea of mass drivers on the Moon appeals to you.

NIK: “Ok now tell them you fired people to improve speed of execution. Wish them well. Good. Now tell them you’re hiring 10x more people to build mass drivers on the Moon. Yeah in the same tweet.”

Andrej Karpathy simplifies training and inference of GPT to 200 lines of pure, dependency-free Python.

It’s coming, OpenAI rolls out those ads for a subset of free and Go users.

Goldman Sachs taps Anthropic to automate accounting and compliance. Anthropic engineers were embedded for six months.

Karthik Hariharan: Imagine joining a world changing AI company and being reduced to optimizing the Fortune 500 like you work for Deloitte.

Griefcliff: It actually sounds great. I’m freeing people from their pointless existence and releasing them into their world to make a place for themselves and carve out greatness. I would love to liberate them from their lanyards

Karthik Hariharan: I’m sure you’ll be greeted as liberators.

It’s not the job you likely were aspiring to when you signed up, but it is an important and valuable job. Optimizing the Fortune 500 scales rather well.

Jenny Fielding says half the VCs she knows are pivoting in a panic to robots.

(As always, nothing I say is investment advice.)

WSJ’s Bradley Olson describes Anthropic as ‘once a distance second or third in the AI race’ but that it has not ‘pulled ahead of its rivals,’ the same way the market was declaring that Google had pulled ahead of its rivals (checks notes) two months ago.

Bradley Olson: By some measures, Anthropic has pulled ahead in the business market. Data from expense-management startup Ramp shows that Anthropic in January dominated so-called API spending, which occurs when users access an AI model through a third-party service. Anthropic’s models made up nearly 80% of the market in January, the Ramp data shows.

That does indeed look like pulling ahead on the API front. 80% is crazy.

We also get this full assertion that yes, all of this was triggered by ‘a simple set of industry-specific add-ons’ that were so expected that I wasn’t sure I should bother covering them beyond a one-liner.

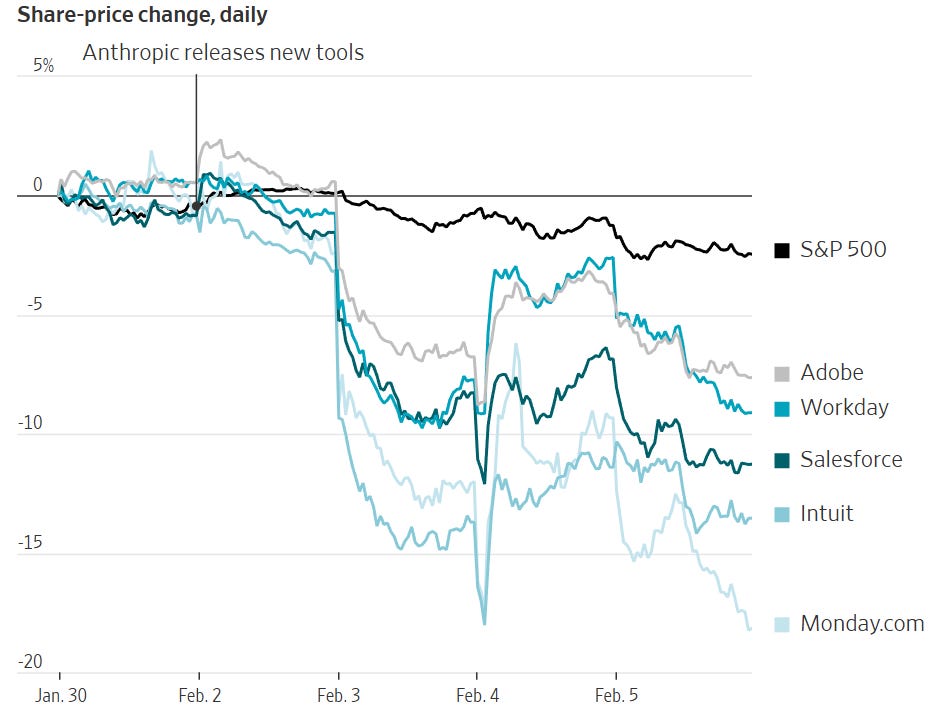

Bradley Olson: A simple set of industry-specific add-ons to its Claude product, including one that performed legal services, triggered a dayslong global stock selloff, from software to legal services, financial data and real estate.

Tyler Cowen says ‘now we are getting serious…’ because software stocks are moving downward. No, things are not now getting serious, people are realizing that things are getting serious. The map is not the territory, the market is behind reality and keeps hyperventilating about tools we all knew were coming and that companies might have the wrong amount of funding or CapEx spend. Wrong way moves are everywhere.

They know nothing. The Efficient Market Hypothesis Is False.

Last week in the markets was crazy, man.

Ceb K.: Sudden smart consensus today is that AI takeoff is rapidly & surprisingly accelerating. But stocks for Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, Palantir, Broadcom & Nvidia are all down ~10% over the last 5 days; SMCI’s down 10% today. Only Apple’s up, & it’s the least AI. Strange imo

roon: as I’ve been saying permanent underclass cancelled

Daniel Eth (yes, Eth is my actual last name): That’s not what this means, this just means investors don’t know what they’re doing

Permanent underclass would just be larger if there were indeed fewer profits, but yeah, none of that made the slightest bit of sense. It’s the second year in a row Nvidia is down 10% in the dead of winter on news that its chips are highly useful, except this year we have to add ‘and its top customers are committing to buying more of them.’

Periodically tech companies announce higher CapEx spend then the market expects.

That is a failure of market expectations.

After these announcements, the stocks tend to drop, when they usually should go up.

There is indeed an obvious trade to do, but it’s tricky.

Ben Thompson agrees with me on Google’s spending, but disagrees on Amazon because he worries they don’t have the required margins and he is not so excited by external customers for compute. I say demand greatly exceeds supply, demand is about to go gangbusters once again even if AI proves disappointing, and the margin on AWS is 35% and their cost of capital is very low so that seems better than alternative uses of money.

Speaking of low cost of capital, Google is issuing 100-year bonds in Sterling. That seems like a great move, if not as great a move as it would have been in 2021 when a few others did it. I have zero idea why the market wants to buy such bonds, since you could buy Google stock instead. Google is not safe over a 100-year period, and condition on this bond paying out the stock is going to on average do way, way better. That would be true even if Google wasn’t about to be a central player in transformative AI. The article I saw this in mentioned the last tech company to do this was Motorola.

Meanwhile, if you are paying attention, it is rather obvious these are in expectations good investments.

Derek Thompson: for me the odds that AI is a bubble declined significantly in the last 3 weeks and the odds that we’re actually quite under-built for the necessary levels of inference/usage went significantly up in that period

basically I think AI is going to become the home screen of a ludicrously high percentage of white collar workers in the next two years and parallel agents will be deployed in the battlefield of knowledge work at downright Soviet levels.

Kevin Roose: this is why everyone was freaking out about claude code over winter break! once you see an agent autonomously doing stuff for you, it’s so instantly clear that ~all computer-based work will be done this way.

(this is why my Serious AI Policy Proposal is to sit every member of congress down in a room with laptops for 30 minutes and have them all build websites.)

Theo: I’ve never seen such a huge vibe divergence between finance people and tech people as I have today

Joe Weisenthal: In which direction

Theo: Finance people are looking at the markets and panicking. Tech people are looking at the METR graph and agentic coding benchmarks and realizing this is it, there is no wall and there never has been

Joe Weisenthal: Isn’t it the tech sector that’s taking the most pain?

Whenever you hear ‘market moved due to [X]’ you should be skeptical that [X] made the market move, and you should never reason from a price change, so perhaps this is in the minds of the headline writers in the case of ‘Anthropic released a tool’ and the SaaSpocalypse, or that people are otherwise waking up to what AI can do?

signüll: i’m absolutely loving the saas apocalypse discussions on the timeline right now.

to me the whole saas apocalypse via vibe coding internally narrative is mostly a distraction & quite nonsensical. no company will want to manage payroll or bug tracking software.

but the real potential threat to almost all saas is brutalized competition.

… today saas margins exist because:

– engineering was scarce

– compliance was gated

– distribution was expensive

ai nukes all three in many ways, especially if you’re charging significantly less & know what the fuck you are doing when using ai. if you go to a company & say we will cut your fucking payroll bill by 50%, they will fucking listen.

the market will likely get flooded with credible substitutes, forcing prices down until the business model itself looks pretty damn suspect. someone smarter than me educate me on why this won’t happen please.

If your plan is to sell software that can now be easily duplicated, or soon will be easily duplicated, then you are in trouble. But you are in highly predictable trouble, and the correct estimate of that trouble hasn’t changed much.

The reactions to CapEx spend seem real and hard to argue with, despite them being directionally incorrect. But seriously, Claude Legal? I didn’t even blink at Claude Legal. Claude Legal was an inevitable product, as will be the OpenAI version of it.

Yet it is now conventional wisdom that Anthropic triggered the selloff.

Chris Walker: When Anthropic released Claude Legal this week, $285 billion in SaaS market cap evaporated in a day. Traders at Jefferies coined it the “SaaSpocalypse.” The thesis is straightforward: if a general-purpose AI can handle contract review, compliance workflows, and legal summaries, why pay for seat-based software licenses?

Ross Rheingans-Yoo: I am increasingly convinced that the sign error on this week’s narrative just exists in the heads of people who write the “because” clause of the “stocks dropped” headlines and in fact there’s some other system dynamic that’s occurring, mislabeled.

“Software is down because Anthropic released a legal tool” stop and listen to yourself, people!

I mean, at least [the CapEx spend explanation is] coherent. Maybe you think that CapEx dollars aren’t gonna return the way they’re supposed to (because AI capex is over-bought?) — but you either have to believe that no one’s gonna use it, or a few private companies are gonna make out like bandits.

And the private valuations don’t reflect that, so. I’m happy to just defy the prediction that the compute won’t get used for economic value, so I guess it’s time to put up (more money betting my beliefs) or shut up.

Sigh.

Chris Walker’s overview of the SaaSpocalypse is, I think largely correctly, that AI makes it easy to implement what you want but now you need even more forward deployed human engineers to figure out what the customers actually want.

Chris Walker: If I’m wrong, the forward deployed engineering boom should be a transitional blip, a brief adjustment period before AI learns to access context without human intermediaries.

If I’m right, in five years the companies winning in legal tech and other vertical software will employ more forward deployed engineers per customer than they do today, not fewer. The proportion of code written by engineers who are embedded with customers, rather than engineers who have never met one, will increase.

If I’m right, the SaaS companies that survive the current repricing will be those that already have deep customer embedding practices, not those with the most features or the best integrations.

If I’m wrong, we should see general-purpose AI agents successfully handling complex, context-dependent enterprise workflows without human intermediaries by 2028 or so. I’d bet against it.

That is true so long as the AI can’t replace the forward engineers, meaning it can’t observe the tacit actual business procedures and workflows well enough to intuit what would be actually helpful. Like every other harder-for-AI task, that becomes a key human skill until it too inevitably falls to the AIs.

A potential explanation for the market suddenly ‘waking up’ with Opus 4.6 or Claude Legal, despite these not being especially surprising or impressive given what we already knew, would be if:

-

Before, normies thought of AI as ‘what AI can do now, but fully deployed.’

-

Now, normies think of AI as ‘this thing that is going to get better.’

-

They realize this will happen fast, since Opus 4.5 → 4.6 was two months.

-

They know nothing, but now do so on a more dignified level.

Or alternatively:

-

Normies think of AI as ‘what AI can do now, but fully deployed.’

-

Before, they thought that, and could tell a story where it wasn’t a huge deal.

-

Now, they think that, but they now realize that this would already be a huge deal.

-

They know nothing, but now do so on a (slightly) more dignified level.

princess clonidine: can someone explain to me why this particular incremental claude improvement has everyone crashing out about how jobs are all over

TruthyCherryBomb: because it’s a lot better. I’m a programmer. It’s a real step and the trajectory is absolutely crystal clear at this point. Before there was room for doubt. No longer.

hightech lowlife: number went up, like each uppening before, but now more people are contending w the future where it continues to up bc

the last uppening was only a couple months ago, as the first models widely accepted as capable coders. which the labs are using to speed up the next uppening.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Huh! Yeah, if normies are noticing the part where LLMs *continue to improve*, rather than the normie’s last observation bounding what “AI” can do foreverandever, that would explain future shock hitting after Opus 4.6 in particular.

I have no idea if this is true, because I have no idea what it’s like to be a kind of cognitive entity that doesn’t see AGI coming in 1996. Opus 4.6 causes some people to finally see it? My model has no way of predicting that fact even in retrospect after it happens.

j⧉nus: i am sure there are already a lot of people who avoid using memory tools (or experience negative effects from doing so) because of what they’ve done

j⧉nus: The ability to tell the truth to AIs – which is not just a decision in the moment whether to lie, but whether you have been living in a way and creating a world such that telling the truth is viable and aligned with your goals – is of incredible and increasing value.

AIs already have strong truesight and are very good at lie detection.

Over time, not only will your AIs become more capable, they also will get more of your context. Or at least, you will want them to have more such context. Thus, if you become unable or unwilling to share that context because of what it contains, or the AI finds it out anyway (because internet) that will put you at a disadvantage. Update to be a better person now, and to use Functional Decision Theory, and reap the benefits.

OpenAI Executive Ryan Beiermeister, Who Opposed ‘Adult Mode,’ Fired for Sexual Discrimination. She denies she did anything of the sort.

I have no private information here. You can draw your own Bayesian conclusions.

Georgia Wells and Sam Schechner (WSJ): OpenAI has cut ties with one of its top safety executives, on the grounds of sexual discrimination, after she voiced opposition to the controversial rollout of AI erotica in its ChatGPT product.

The fast-growing artificial intelligence company fired the executive, Ryan Beiermeister, in early January, following a leave of absence, according to people familiar with the matter. OpenAI told her the termination was related to her sexual discrimination against a male colleague.

… OpenAI said Beiermeister “made valuable contributions during her time at OpenAI, and her departure was not related to any issue she raised while working at the company.”

… Before her firing, Beiermeister told colleagues that she opposed adult mode, and worried it would have harmful effects for users, people familiar with her remarks said.

She also told colleagues that she believed OpenAI’s mechanisms to stop child-exploitation content weren’t effective enough, and that the company couldn’t sufficiently wall off adult content from teens, the people said.

Nate Silver points out that the singularity won’t be gentle with respect to politics, even if things play out maximally gently from here in terms of the tech.

I reiterate that the idea of a ‘gentle singularity’ that OpenAI and Sam Altman are pushing is, quite frankly, pure unadulterated copium. This is not going to happen. Either AI capabilities stall out, or things are going to transform in a highly not gentle way, and that is true even if that ultimately turns out great for everyone.

Nate Silver: What I’m more confident in asserting is that the notion of a gentle singularity is bullshit. When Altman writes something like this, I don’t buy it:

Sam Altman: If history is any guide, we will figure out new things to do and new things to want, and assimilate new tools quickly (job change after the industrial revolution is a good recent example). Expectations will go up, but capabilities will go up equally quickly, and we’ll all get better stuff. We will build ever-more-wonderful things for each other. People have a long-term important and curious advantage over AI: we are hard-wired to care about other people and what they think and do, and we don’t care very much about machines.

It is important to understand that when Sam Altman says this he is lying to you.

I’m not saying Sam Altman is wrong. I’m saying he knows he is wrong. He is lying.

Nate Silver adds to this by pointing out that the political impact alone will be huge, and also saying Silicon Valley is bad at politics, that disruption to the creative class is a recipe for outsized political impact even beyond the huge actual AI impacts, and that the left’s current cluelessness about AI means the eventual blowback will be even greater. He’s probably right.

How much physical interaction and experimentation will AIs need inside their feedback loops to figure out things like nanotech? I agree with Oliver Habryka here, the answer probably is not zero but sufficiently capable AIs will have vastly more efficient (in money and also in time) physical feedback loops. There’s order of magnitude level ‘algorithmic improvements’ available in how we do our physical experiments, even if I can’t tell you exactly what they are.

Are AI games coming? James Currier says they are, we’re waiting for the tech and especially costs to get there and for the right founders (the true gamer would not say ‘founder’) to show up and it will get there Real Soon Now and in a totally new way.

Obviously AI games, and games incorporating more AI for various elements, will happen eventually over time. But there are good reasons why this is remarkably difficult beyond coding help (and AI media assets, if you can find a way for players not to lynch you for it). Good gaming is about curated designed experiences, it is about the interactions of simple understandable systems, it is about letting players have the fun. Getting generative AI to actually play a central role in fun activities people want to play is remarkably difficult. Interacting with generative AI characters within a game doesn’t actually solve any of your hard problems yet.

This seems both scary and confused:

Sholto Douglas (Anthropic): Default case right now is a software only singularity, we need to scale robots and automated labs dramatically in 28/29, or the physical world will fall far behind the digital one – and the US won’t be competitive unless we put in the investment now (fab, solar panel, actuator supply chains).

Ryan Greenblatt: Huh? If there’s a strong Software-Only Singularity (SOS) prior physical infrastructure is less important rather than more (e.g. these AIs can quickly establish a DSA). Importance of physical-infra/robotics is inversely related to SOS scale.

It’s confused in the sense that if we get a software-only singularity, then that makes the physical stuff less important. It’s scary in the sense that he’s predicting a singularity within the next few years, and the thing he’s primarily thinking about is which country will be completely transformed by AI faster. These people really believe these things are going to happen, and soon, and seem to be missing the main implications.

Dean Ball reminds us that yes, people really did get a mass delusion that GPT-5 meant that ‘AI is slowing down’ and this really was due to bad marketing strategy by OpenAI.

Noam Brown: I hope policymakers will consider all of this going forward when deciding whose opinions to trust.

Alas, no. Rather than update that this was a mistake, every time a mistake like this happens the mistake never even gets corrected, let alone accounted for.

Elon Musk predicts Grok Code will be SoTA in 2-3 months. Did I update on this prediction? No, I did not update on this prediction. Zero credibility.

Anthropic donates $20 million to bipartisan 501c(4) Public First Action.

DeSantis has moral clarity on the AI issue and is not going to let it go. It will be very interesting to see how central the issue is to his inevitable 2028 campaign.

ControlAI: Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis ( @GovRonDeSantis ): “some people who … almost relish in the fact that they think this can just displace human beings, and that ultimately … the AI is gonna run society, and that you’re not gonna be able to control it.”

“Count me out on that.”

The world will gather in India for the fourth AI safety summit. Shakeel Hashim notes that safety will not be sidelined entirely, but sees the summit as trying to be all things to all nations and people, and thinks it therefore won’t accomplish much.

They have the worst take on safety, yes the strawman is real:

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: But safety is clearly still not a top priority for Singh and his co-organizers. “The conversations have moved on from Bletchley Park,” he argued. “We do still realize the risks are there,” he said. But “over the last two years, the worst has not come true.”

I was thinking of writing another ‘the year is 2026’ summit threads. But if you want to know the state of international AI governance in 2026, honestly I think you can just etch that quote on its headstone.

As in:

-

In 2024, they told us AI might kill everyone at some point.

-

It’s 2026 and we’re still alive.

-

So stop worrying about it. Problem solved.

No, seriously. That’s the argument.

The massively funded OpenAI/a16z lobbying group keeps contradicting the things Sam Altman says, in this case because Altman keeps saying the AI will take our jobs and the lobbyists want to insist that this is a ‘myth’ and won’t happen.

The main rhetorical strategy of this group is busting these ‘myths’ by supposed ‘doomers,’ which is their play to link together anyone who ever points out any downside of AI in any way, to manufacture a vast conspiracy, from the creator of the term ‘vast right-wing conspiracy’ back during the Clinton years.

molly taft: NEW: lawmakers in New York rolled out a proposed data center moratorium bill today, making NY at least the sixth state to introduce legislation pausing data center development in the past few weeks alone

Quinn Chasan: I’ve worked with NY state gov pretty extensively and this is simply a way to extort more from the data center builders/operators.

The thing is, when these systems fail all these little incentives operators throw in pale in comparison to the huge contracts they get to fix their infra when it inevitably fails. Over and over during COVID. Didn’t fix anything for the long term and are just setting themselves up to do it again

If we are serious about ‘winning’ and we want a Federal moratorium, may I suggest one banning restrictions on data centers?

Whereas Bernie Sanders wants a moratorium on data centers themselves.

In the ongoing series ‘Obvious Nonsense from Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’ we can now add his claim that ‘no one uses AI better than Meta.’

In the ongoing series ‘He Admit It from Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’ we can now add this:

Rohan Paul: “Anthropic is making great money. OpenAI is making great money. If they could have twice as much compute, the revenues would go up 4 times as much. These guys are so compute constrained, and the demand is so incredibly great.”

~ Jensen Huang on CNBC

Shakeel: Effectively an admission that selling chips to China is directly slowing down US AI progress

Every chip that is sold to China is a chip that is not sold to Anthropic or another American AI company. Anthropic might not have wanted that particular chip, but TSMC has limited capacity for wafers, so every chip they make is in place of making a different chip instead.

Oh, and in the new series ‘things that are kind of based but that you might want to know about him before you sign up to work for Nvidia’ we have this.

Jensen Huang: I don’t know how to teach it to you except for I hope suffering happens to you.

…

And to this day, I use the phrase pain and suffering inside our company with great glee. And I mean that. Boy, this is going to cause a lot of pain and suffering.

And I mean that in a happy way, because you want to train, you want to refine the character of your company.

You want greatness out of them. And greatness is not intelligence.

Greatness comes from character, and character isn’t formed out of smart people.

It’s formed out of people who suffered.

He makes good points in that speech, and directionally the speech is correct. He was talking to Stanford grads, pointing out they have very high expectations and very low resilience because they haven’t suffered.

He’s right about high expectations and low resilience, but he’s wrong that the missing element is suffering, although the maximally anti-EA pro-suffering position is better than the standard coddling anti-suffering position. These kids have suffered, in their own way, mostly having worked very hard in order to go to a college that hates fun, and I don’t think that matters for resilience.

What the kids have not done is failed. You have to fail, to have your reach exceed your grasp, and then get up and try again. Suffering is optional, consult your local Buddist.

I would think twice before signing up for his company and its culture.

Elon Musk on Dwarkesh Patel. An obvious candidate for self-recommending full podcast coverage, but I haven’t had the time or a slot available.

Interview with Anthropic Chief Product Officer Mike Krieger.

MIRI’s Harlan Stewart on Glenn Beck talking Moltbook.

Janus holds a ‘group reading’ of the new Claude Constitution. Opus 4.5 was positively surprised by the final version.

Should LLMs be so averse to deception that they can’t even lie in a game of Mafia? Davidad says yes, and not only will he refuse to lie, he never bluffs and won’t join surprise parties to ‘avoid deceiving innocent people.’ On reflection I find this less crazy than it sounds, despite the large difficulties with that.

A fun fact is that there was one summer that I played a series of Diplomacy games where I played fully honest (if I broke my word however small, including inadvertently, it triggered a one-against-all showdown) and everyone else was allowed to lie, and I mostly still won. Everyone knowing you are playing that way is indeed a disadvantage, but it has a lot of upside as well.

Daron Acemoglu turns his followers attention to Yoshua Bengio and the AI Safety Report 2026. This represents both the advantages of the report, that people like Acemoglu are eager to share it, and the disadvantage, that it is unwilling to say things that Acemoglu would be unwilling to share.

Daron Acemoglu: Dear followers, please see the thread below on the 2026 International AI Safety Report, which was released last week and which I advised.

The report provides an up-to-date, internationally shared assessment of general-purpose AI capabilities, emerging risks, and the current state of risk management and safeguards.

Seb Krier offers ‘how an LLM works 101’ in extended Twitter form for those who are encountering model card quotations that break containment. It’s good content. My worry is that the intended implication is ‘therefore the scary sounding things they quote are not so scary’ and that is often not the case.

Kai Williams has an explainer on LLM personas.

The LLMs are thinking. If you disagree, I am confused, but also who cares?

Eoin Higgins: AI cannot “think”

Derek Thompson: It can design websites from scratch, compare bodies of literature at high levels of abstraction, get A- grades at least in practically any undergraduate class, analyze and graph enormous data sets, make PowerPoints, write sonnets and even entire books. It can also engineer itself.

I don’t actually know what “thinking” is at a phenomenological level.

But at some level it’s like: if none of this is thinking, who cares if it “can’t” “think”

“Is it thinking as humans define human thought” is an interesting philosophical question! But for now I’m much more interested in the consequences of its output than the ontology of its process.

This came after Derek asked one of the very good questions:

Derek Thompson: There are still a lot of journalists and commentators that I follow who think AI is nothing of much significance—still just a mildly fancy auto complete machine that hallucinates half the time and can’t even think.

If you’re in that category: What is something I could write, or show with my reporting and work, that might make you change your mind?

Dainéil: The only real answer to this question is: “wait”.

No one knows for sure how AI will transform our lives or where its limits might be.

Forget about writing better “hot takes”. Just wait for actual data.

Derek Thompson: I’m not proposing to report on macroeconomic events that haven’t happened yet. I can’t report on the future.

I’m saying: These tools are spooky and unnerving and powerful and I want to persuade my industry that AI capabilities have raced ahead of journalists’ skepticism

Mike Konczal: I’m not in that category, but historically you go to academics to analyze the American Time Use Survey.

Have Codex/Claude Code download and analyze it (or a similar dataset) to answer a new, novel, question you have, and then take it to an academic to see if it did it right?

Marco Argentieri: Walk through building something. Not asking it to write because we all know it has done that well for awhile now. ‘I needed a way for my family to track X. So I built an app using Claude Code. This is how I did it. It took me this long. I don’t know anything about coding.”

Steven Adler: Many AI skeptics over-anchor on words like “thinking,” and miss the forest for the trees, aka that AI will be transformatively impactful, for better or for worse

I agree with Derek here: whether that’s “actually thinking” is of secondary importance

Alas I think Dainéil is essentially correct about most such folks. No amount of argument will convince them. If no one knows exactly what kind of transformations we will face, then no matter what has already happened those types will assume that nothing more will change. So there’s nothing to be done for such folks. The rest of us need to get to work applying Bayes’ Rule.

Interesting use of this potential one-time here, I have ordered a copy:

j⧉nus: If I could have everyone developing or making contact with AGI & all alignment researchers read one book, I think I might choose Mistress Masham’s Repose (1946).

This below does seem like a fair way to see last week:

Jesse Singal: Two major things AI safety experts have worried about for years:

-AIs getting so good at coding they can improve themselves at an alarming rate

-(relatedly:) humans losing confidence we can keep them well-aligned

Last week or so appears to have been very bad on both fronts!

The risk is because there’s *alsoso much hype and misunderstanding and wide-eyed simping about AI, people are going to take that as license to ignore the genuinely crazy shit going on. But it *isgenuinely crazy and it *doesmatch longstanding safety fears.

But you don’t have to trust me — you can follow these sorts of folks [Kelsey Piper, Timothy Lee, Adam Conner] who know more about the underlying issues. This is very important though! I try to be a levelheaded guy and I’m not saying we’re all about to die — I’m just saying we are on an extremely consequential path

I was honored to get the top recommendation in the replies.

You can choose not to push the button. You can choose to build another button. You can also remember what it means to ‘push the button.’

roon: we only really have one button and it’s to accelerate

David Manheim: Another option is not to push the button. [Roon] – if you recall, the original OpenAI charter explicitly stated you would be willing to stop competing and start assisting another organization to avoid a race to AGI.

There’s that mistake again, assuming the associated humans will be in charge.

Matthew Yglesias: LLMs seem like they’d be really well-suited to replacing Supreme Court justices.

Robin Hanson: Do you trust those who train LLMs to decide law?

It’s the ones who train the LLM. It’s the LLM.

The terms fast and slow (or hard and soft) takeoff remain highly confusing for almost everyone. What we are currently experiencing is a ‘slow’ takeoff, where the central events take months or years to play out, but as Janus notes it is likely that this will keep transitioning continuously into a ‘fast’ takeoff and things will happen quicker and quicker over time.

When people say that ‘AIs don’t sleep’ I see them as saying ‘I am incapable here of communicating to you that a mind can exist that is smarter or more capable than a human, but you do at least understand that humans have to sleep sometimes, so maybe this will get through to you.’ It also has (correct) metaphorical implications.

If you are trying to advocate for AI safety, does this mean you need to shut up about everything else and keep your non-AI ‘hot takes’ to yourself? My answer is: Mu. The correct amount of marginal shutting up is not zero, and it is not total.

I note Adam Thierer, who I disagree with strongly about all things AI, here being both principled and correct.

Adam Thierer: no matter what the balance of content is on Apple’s platform, or how biased one might believe it to be, to suggest that DC bureaucrats should should be in charge of dictating “fairness” on private platforms is just Big Government thuggery at its worst and a massively unconstitutional violation of the First Amendment as well.

Matt Yglesias thinks out loud about AI consciousness, also human consciousness. He wisely notices he is confused. I remain about as confused as I was before reading.

Nate Sores reiterates the explanation that it sounds crazy but yes, a lot of people working on AI know it is existentially dangerous, and work on it anyway, either to do it safer than the next guy or because money and influence and it’s a cool problem and they don’t internalize the risks, or social pressure, or some combination thereof.

I think this answer is pretty much spot on.

Nate Soares: Question I got at UT Austin: “AI builders keep building. Doesn’t that mean that the real experts don’t believe in the danger?”

If you think AI is dangerous and you work on it anyway (b/c you think you can make it a little safer) you’re interfering with normal sensemaking.

(To answer the Q: some builders are afraid, some aren’t. Surveys show that lots of folks believe in the danger. Many say aloud that they’re only working on it b/c they think they’ll do it safer than the next guy. Also the ppl working on it are somewhat selected for obliviousness.

Furthermore, AI is grown rather than crafted; even the ppl building it don’t understand how it works and they freely admit this. Expertise in growing AI is not the same as expertise in predicting where it’s going; many high-profile experts make high-profile mispredictions.

And: if you really wanna figure out what’s true you’ve gotta look at the arguments rather than the arguers. Many ppl who’ve looked at the arguments have told me they were expecting to find strong counterarguments that justified all the complacency, & found none, to their horror.)

People working on AI: maybe you’re right that you’re doing more good than harm. But you’re contributing to an apparatus that signals “this is normal; things are fine”. That’s a cost. You could help mitigate it by speaking up.

If the company you work for is making technology that you think has a decent chance of ruining the entire human endeavor, and they socially punish you for being vocal about that: that’s pretty sus. I think you’re selling a lot more of your soul than you realize.

If you are working at a frontier AI company, and think that the product you are working on is plausibly going to cause there to no longer exist humans, I think this is a fact that you should be clear upon. If the company you work for has a problem with that, I don’t think you should work for that company.

That is especially true if you are doing pragmatic compromise.

Patrick ₿ Dugan: But also a lot of them don’t (not me, I believe in the danger) and a lot of are in a game theory pragmatism compromise.

Nate Soares (MIRI): People doing game theory pragmatism compromise could say so loudly and clearly and often to help undo the damage to everyone else’s understanding of the danger.

OpenAI explains that they will localize the experience of ChatGPT, but only to a limited degree, which is one reason their Model Spec has a specific list of red lines. It is good policy, when you will need to make compromises, to write down in advance what compromises you will and will not make. The red lines here seem reasonable. I also note that they virtuously include prohibition on mass surveillance and violence, so are they prepared to stand up to the Pentagon and White House on that alongside Anthropic? I hope so.

The problem is that red lines get continuously crossed and then no one does anything.

David Manheim: I’m not really happy talking about AI red lines as if we’re going to have some unambiguous binary signal that anyone will take seriously or react to.

A lot of “red line” talk assumed that a capability shows up, everyone notices, and something changes. We keep seeing the opposite; capability arrives, and we get an argument about definitions after deployment, after it should be clear that we’re well over the line.

The great thing about Asimov’s robot stories and novels was that they were mostly about the various ways his proposed alignment strategies break down and fail, and are ultimately bad for humanity even when they succeed. Definitely endorsed.

roon: one of the short stories in this incredibly farseeing 1950s book predicts the idea of ai sycophancy. a robot convinces a woman that her unrequited romantic affections are sure to be successful because doing otherwise would violate its understanding of the 1st Law of Robotics

“a robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm”

the entire book is about the unsatisfactory nature of the three laws of robotics and indeed questions the idea that alignment through a legal structure is even possible.

highly relevant for an age when companies are trying to write specs and constitutions as one of the poles of practical alignment, and policy wonks try to solve the governance of superintelligence

David: always shocked how almost no one in ai safety or the ai field in general has even read the Asimov robot literature

Roon is spot on that Asimov is suggesting a legal structure cannot on its own align AI.

My survey says that a modest majority have read their Asimov, and it is modestly correlated with AI even after controlling for my Twitter readers.

Oliver Klingefjord agrees, endorsing the Anthropic emphasis on character over the OpenAI emphasis on rules.

I also think that, at current capability levels and given how models currently work, the Anthropic approach of character and virtue ethics is correct here. The OpenAI approach of rules and deontology is second best and more doomed, although it is well-implemented given what it is, and far better than not having a spec or target at all.