It’s hunting season in orbit as Russia’s killer satellites mystify skywatchers

“Once more, we play our dangerous game—a game of chess—against our old adversary.”

In this pool photograph distributed by the Russian state media agency Sputnik, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin gives a speech during the Victory Day military parade at Red Square in central Moscow on May 9, 2025. Credit: Yacheslav Prokofyev/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

Russia is a waning space power, but President Vladimir Putin has made sure he still has a saber to rattle in orbit.

This has become more evident in recent weeks, when we saw a pair of rocket launches carrying top-secret military payloads, the release of a mysterious object from a Russian mothership in orbit, and a sequence of complex formation-flying maneuvers with a trio of satellites nearly 400 miles up.

In isolation, each of these things would catch the attention of Western analysts. Taken together, the frenzy of maneuvers represents one of the most significant surges in Russian military space activity since the end of the Cold War. What’s more, all of this is happening as Russia lags further behind the United States and China in everything from rockets to satellite manufacturing. Russian efforts to develop a reusable rocket, field a new human-rated spacecraft to replace the venerable Soyuz, and launch a megaconstellation akin to SpaceX’s Starlink are going nowhere fast.

Russia has completed just eight launches to orbit so far this year, compared to 101 orbital attempts by US launch providers and 36 from China. This puts Russia on pace for the fewest number of orbital launch attempts since 1961, the year Soviet citizen Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space.

For the better part of three decades, Russia’s space program could rely on money from Western governments and commercial companies to build rockets, launch satellites, and ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station. The money tap dried up after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia also lost access to Ukrainian-made components to go into their launch vehicles and satellites.

Chasing a Keyhole

Amid this retrenchment, Russia is targeting what’s left of its capacity for innovation in space toward pestering the US military. US intelligence officials last year said they believed Russia was pursuing a project to place a nuclear weapon in space. The detonation of a nuclear bomb in orbit could muck up the space environment for years, indiscriminately disabling countless satellites, whether they’re military or civilian.

Russia denied that it planned to launch a satellite with a nuclear weapon, but the country’s representative in the United Nations vetoed a Security Council resolution last year that would have reaffirmed a nearly 50-year-old ban on placing weapons of mass destruction into orbit.

While Russia hasn’t actually put a nuclear bomb into orbit yet, it’s making progress in fielding other kinds of anti-satellite systems. Russia destroyed one of its own satellites with a ground-launched missile in 2021, and high above us today, Russian spacecraft are stalking American spy satellites and keeping US military officials on their toes with a rapid march toward weaponizing space.

The world’s two other space powers, the United States and China, are developing their own “counter-space” weapons. But the US and Chinese militaries have largely focused on using their growing fleets of satellites as force multipliers in the terrestrial domain, enabling precision strikes, high-speed communications, and targeting for air, land, and naval forces. That is starting to change, with US Space Force commanders now openly discussing their own ambitions for offensive and defensive counter-space weapons.

Three of Russia’s eight orbital launches this year have carried payloads that could be categorized as potential anti-satellite weapons, or at least prototypes testing novel technologies that could lead to one. (For context, three of Russia’s other launches this year have gone to the International Space Station, and two launched conventional military communications or navigation satellites.)

One of these mystery payloads launched on May 23, when a Soyuz rocket boosted a satellite into a nearly 300-mile-high orbit perfectly aligned with the path of a US spy satellite owned by the National Reconnaissance Office. The new Russian satellite, designated Kosmos 2588, launched into the same orbital plane as an American satellite known to the public as USA 338, which is widely believed to be a bus-sized KH-11, or Keyhole-class, optical surveillance satellite.

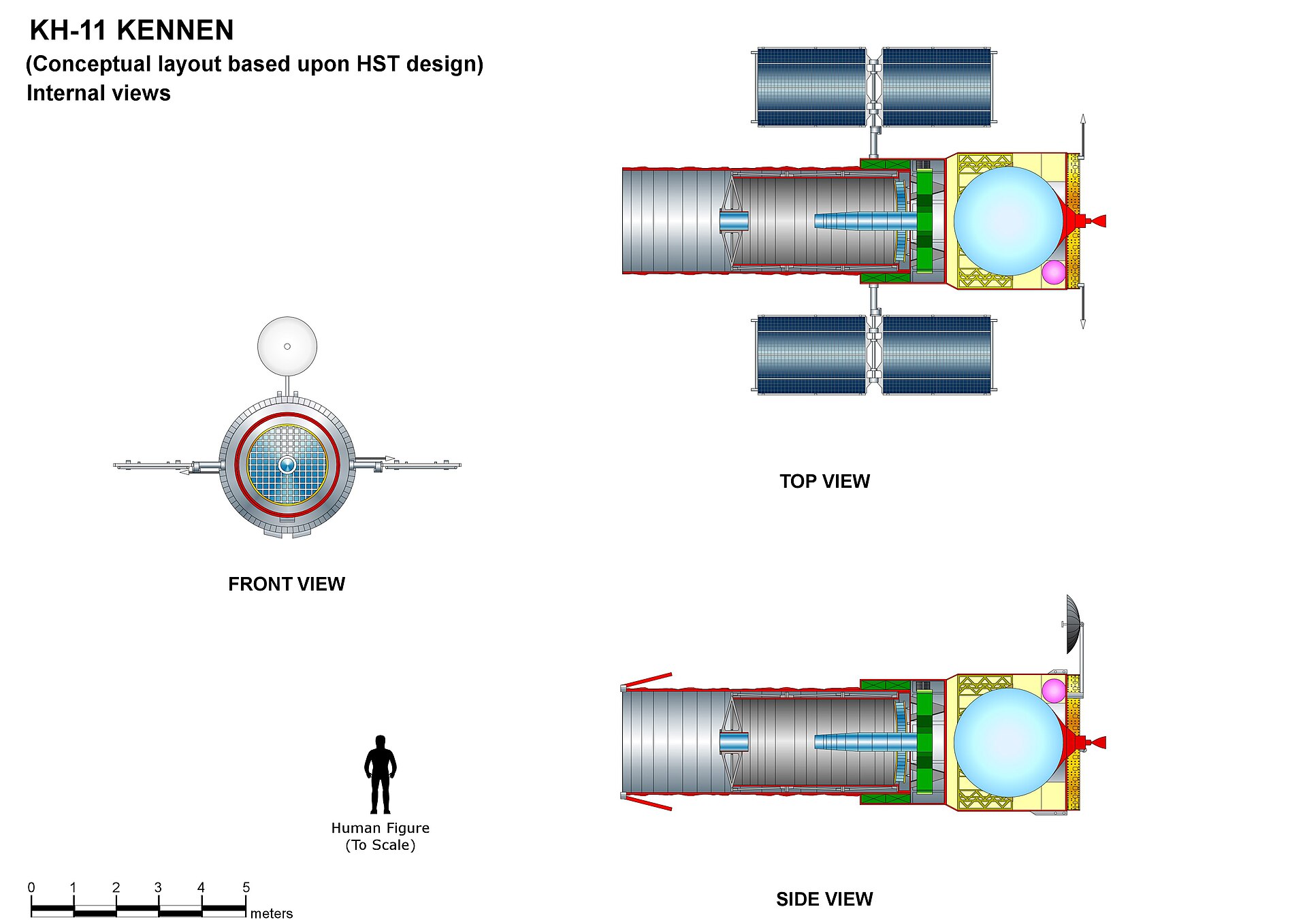

A conceptual drawing of a KH-11 spy satellite, with internal views, based on likely design similarities to NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: Giuseppe De Chiara/CC BY-SA 3.0

The governments of Russia and the United States use the Kosmos and USA monikers as cover names for their military satellites.

While their exact design and capabilities are classified, Keyhole satellites are believed to provide the sharpest images of any spy satellite in orbit. They monitor airfields, naval ports, missile plants, and other strategic sites across the globe. In the zeitgeist of geopolitics, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea are the likeliest targets for the NRO’s Keyhole satellites. To put it succinctly, Keyhole satellites are some of the US government’s most prized assets in space.

Therefore, it’s not surprising to assume a potential military adversary might want to learn more about them or be in a position to disable or destroy them in the event of war.

Orbital ballet

A quick refresher on orbital mechanics is necessary here. Satellites orbit the Earth in flat planes fixed in inertial space. It’s not a perfect interpretation, but it’s easiest to understand this concept by imagining the background of stars in the sky as a reference map. In the short term, the position of a satellite’s orbit will remain unchanged on this reference map without any perturbation. For something in low-Earth orbit, Earth’s rotation presents a different part of the world to the satellite each time it loops around the planet.

It takes a lot of fuel to make changes to a satellite’s orbital plane, so if you want to send a satellite to rendezvous with another spacecraft already in orbit, it’s best to wait until our planet’s rotation brings the launch site directly under the orbital plane of the target. This happens twice per day for a satellite in low-Earth orbit.

That’s exactly what Russia is doing with a military program named Nivelir. In English, Nivelir translates to “dumpy level”—an optical instrument used by builders and surveyors.

The launch of Kosmos 2588 in May was precisely timed for the moment Earth’s rotation brought the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia underneath the orbital plane of the NRO’s USA 338 Keyhole satellite. Launches to the ISS follow the same roadmap, with crew and cargo vehicles lifting off at exactly the right time—to the second—to intersect with the space station’s orbital plane.

Since 2019, Russia has launched four satellites into bespoke orbits to shadow NRO spy satellites. None of these Russian Nivelir spacecraft have gotten close to their NRO counterparts. The satellites have routinely passed dozens of miles from one another, but the similarities in their orbits would allow Russia’s spacecraft to get a lot closer—and theoretically make physical contact with the American satellite. The Nivelir satellites have even maneuvered to keep up with their NRO targets when US ground controllers have made small adjustments to their orbits.

“This ensures that the orbital planes do not drift apart,” wrote Marco Langbroek, a Dutch archaeologist and university lecturer on space situational awareness. Langbroek runs a website cataloguing military space activity.

This is no accident

There’s reason to believe that the Russian satellites shadowing the NRO in orbit might be more than inspectors or stalkers. Just a couple of weeks ago, another Nivelir satellite named Kosmos 2558 released an unknown object into an orbit that closely mirrors that of an NRO spy satellite named USA 326.

We’ve seen this before. An older Nivelir satellite, Kosmos 2542, released a sub-satellite shortly after launching in 2019 into the same orbital plane as the NRO’s USA 245 satellite, likely a KH-11 platform similar to the USA 338 satellite now being shadowed by Kosmos 2588.

After making multiple passes near the USA 245 spacecraft, Kosmos 2542’s sub-satellite backed off and fired a mysterious projectile in 2020 at a speed fast enough to damage or destroy any target in its sights. US military officials interpreted this as a test of an anti-satellite weapon.

Now, another Russian satellite is behaving in the same way, with a mothership opening up to release a smaller object that could in turn reveal its own surprise inside like a Matryoshka nesting doll. This time, however, the doll is unnesting nearly three years after launch. With Kosmos 2542, this all unfolded within months of arriving in space.

The NRO’s USA 326 satellite launched in February 2022 aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California. It is believed to be an advanced electro-optical reconnaissance satellite, although the circumstances of its launch suggest a design different from the NRO’s classic Keyhole spy satellites. Credit: SpaceX

In just the last several days, the smaller craft deployed by Kosmos 2558—designated “Object C”—lowered its altitude to reach an orbit in resonance with USA 326, bringing it within 60 miles (100 kilometers) of the NRO satellite every few days.

While US officials are worried about Russian anti-satellite weapons, or ASATs, the behavior of Russia’s Nivelir satellites is puzzling. It’s clear that Russia is deliberately launching these satellites to get close to American spy craft in orbit, a retired senior US military space official told Ars on background.

“If you’re going to launch a LEO [low-Earth orbit] satellite into the exact same plane as another satellite, you’re doing that on purpose,” said the official, who served in numerous leadership positions in the military’s space programs. “Inclination is one thing. We put a bunch of things into Sun-synchronous orbits, but you have a nearly boundless number of planes you can put those into—360 degrees—and then you can go down to probably the quarter-degree and still be differentiated as being a different plane. When you plane-match underneath that, you’re doing that on purpose.”

But why?

What’s not as obvious is why Russia is doing this. Lobbing an anti-satellite, or counter-space, weapon into the same orbital plane as its potential target ties Russia’s hands. Also, a preemptive strike on an American satellite worth $1 billion or more could be seen as an act of war.

“I find it strange that the Russians are doing that, that they’ve invested their rubles in a co-planar LEO counter-space kind of satellite,” the retired military official said. “And why do I say that? Because when you launch into that plane, you’re basically committed to that plane, which means you only have one potential target ever.”

A ground-based anti-satellite missile, like the one Russia tested against one of its own satellites in 2021, could strike any target in low-Earth orbit.

“So why invest in something that is so locked into a target once you put it up there, when you have the flexibility of a ground launch case that’s probably even cheaper?” this official told Ars. “I’d be advocating for more ground-launched ASATs if I really wanted the flexibility to go after new payloads, because this thing can never go after anything new.”

“The only way to look at it is that they’re sending us messages. You say, ‘Hey, I’m going to just annoy the hell out of you. I’m going to put something right on your tail,'” the official said. “And maybe there’s merit to that, and they like that. It doesn’t make sense from a cost-benefit or an operational flexibility perspective, if you think about it, to lock in on a single target.”

Nevertheless, Russia’s Nivelir satellites have shown they could fire a projectile at another spacecraft in orbit, so US officials don’t dismiss the threat. Slingshot Aerospace, a commercial satellite tracking and analytics firm, went straight to the point in its assessment: “Kosmos 2588 is thought to be a Nivelir military inspection satellite with a suspected kinetic weapon onboard.”

Langbroek agrees, writing that he is concerned that Russia might be positioning “dormant” anti-satellite weapons within striking distance of NRO spy platforms.

“To me, the long, ongoing shadowing of what are some of the most prized US military space assets, their KH-11 Advanced Enhanced Crystal high-resolution optical IMINT (imaging intelligence) satellites, is odd for ‘just’ an inspection mission,” Langbroek wrote.

American pilot Francis Gary Powers, second from right, in a Moscow courtroom during his trial on charges of espionage after his U-2 spy plane was shot down while working for the CIA. Credit: Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images

The US military’s ability to spy over vast swaths of Russian territory has been a thorn in Russia’s side since the height of the Cold War.

“They thought they had the edge and shot down Gary Powers,” the retired official said, referring to the Soviet Union’s shoot-down of an American U-2 spy plane in 1960. “They said, ‘We’re going to keep those Americans from spying on us.’ And then they turn around, and we’ve got spy satellites. They’ve always hated them since the 1960s, so I think there’s still this cultural thing out there: ‘That’s our nemesis. We hate those satellites. We’re just going to fight them.'”

Valley of the dolls

Meanwhile, the US Space Force and outside analysts are tracking a separate trio of Russian satellites engaged in a complex orbital dance with one another. These satellites, numbered Kosmos 2581, 2582, and 2583, launched together on a single rocket in February.

While these three spacecraft aren’t shadowing any US spy satellites, things got interesting when one of the satellites released an unidentified object in March in a similar way to how two of Russia’s Nivelir spacecraft have deployed their own sub-satellites.

Kosmos 2581 and 2582 came as close as 50 meters from one another while flying in tandem, according to an analysis by Bart Hendrickx published in the online journal The Space Review earlier this year. The other member of the trio, Kosmos 2583, released its sub-satellite and maneuvered around it for about a month, then raised its orbit to match that of Kosmos 2581.

Finally, in the last week of June, Kosmos 2582 joined them, and all three satellites began flying close to one another, according to Langbroek, who called the frenzy of activity one of the most complex rendezvous and proximity operations exercises Russia has conducted in decades.

Higher still, two more Russian satellites are up to something interesting after launching on June 19 on Russia’s most powerful rocket. After more than 30 years in development, this was the first flight of Russia’s Angara A5 rocket, with a real functioning military satellite onboard, following four prior test launches with dummy payloads.

The payload Russia’s military chose to launch on the Angara A5 is unusual. The rocket deployed its primary passenger, Kosmos 2589, into a peculiar orbit hugging the equator and ranging between approximately 20,000 (12,500 miles) and 51,000 kilometers (31,700 miles) in altitude.

In this orbit, Kosmos 2589 completes a lap around the Earth about once every 24 hours, giving the satellite a synchronicity that allows it to remain nearly fixed in the sky over the same geographic location. These kinds of geosynchronous, or GEO, orbits are usually circular, with a satellite maintaining the same altitude over the equator.

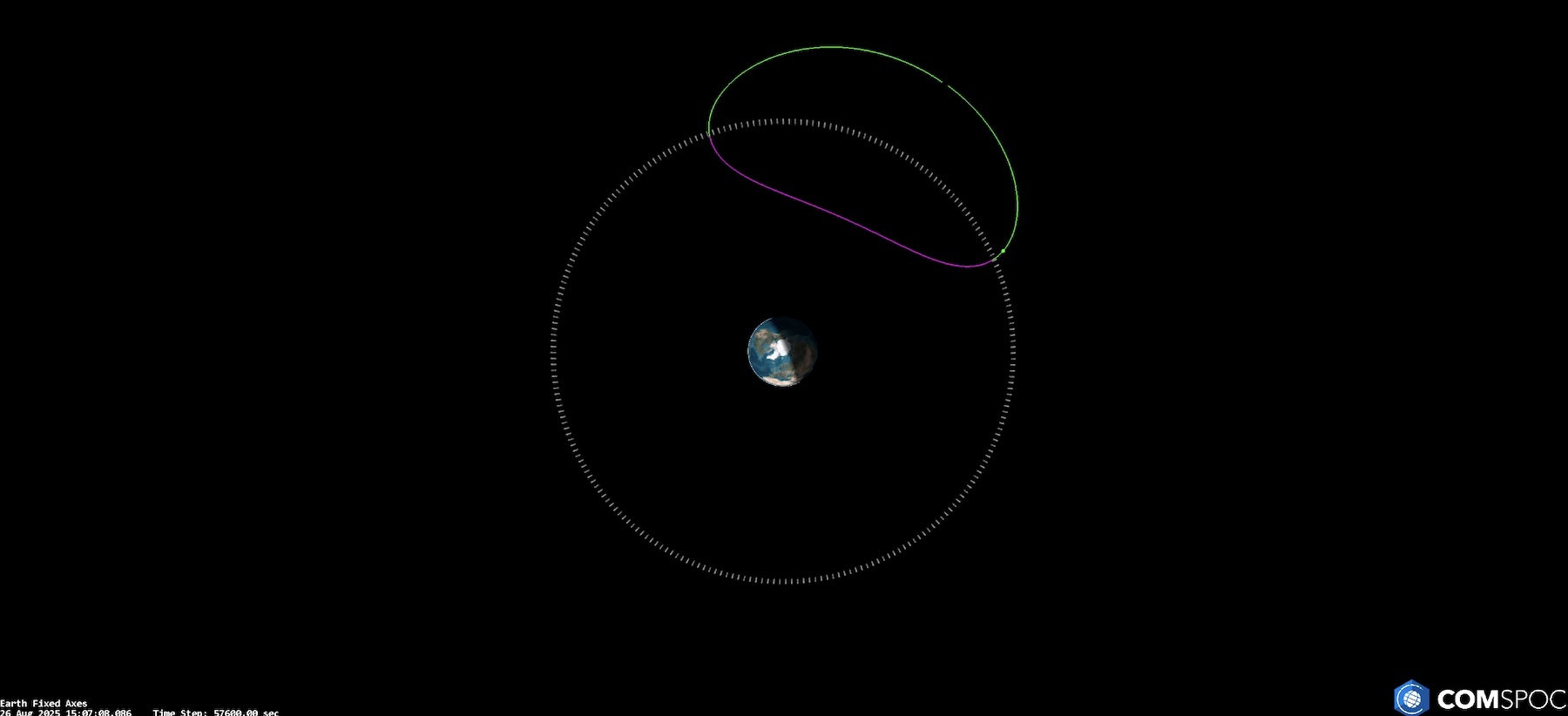

The orbits of Kosmos 2589 and its companion satellite, illustrated in green and purple, bring the two Russian spacecraft through the geostationary satellite belt twice per day. Credit: COMSPOC

But Kosmos 2589 is changing altitude throughout its day-long orbit. Twice per day, on the way up and back down, Kosmos 2589 briefly passes near a large number of US government and commercial satellites in more conventional geosynchronous orbits but then quickly departs the vicinity. At a minimum, this could give Russian officials the ability to capture close-up views of American spy satellites.

Then, a few days after Kosmos 2589 reached orbit last month, commercial tracking sensors detected a second object nearby. Sound familiar? This new object soon started raising its altitude, and Kosmos 2589 followed suit.

Aiming higher

Could this be the start of an effort to extend the reach of Russian inspectors or anti-satellite weapons into higher orbits after years of mysterious activity at lower altitudes?

Jim Shell, a former NRO project manager and scientist at Air Force Space Command, suggested the two satellites seem positioned to cooperate with one another. “Many interesting scenarios here such as ‘spotter shooter’ among others. Certainly something to keep eyes on!” Shell posted Saturday on X.

COMSPOC, a commercial space situational awareness company, said the unusual orbit of Kosmos 2589 and its companion put the Russian satellites in a position to, at a minimum, spy on Western satellites in geosynchronous orbit.

“This unique orbit, which crosses two key satellite regions daily, may aid in monitoring objects in both GEO and graveyard orbits,” COMSPOC wrote on X. “Its slight 1° inclination could also reduce collision risks. While the satellite’s mission remains unclear, its orbit suggests interesting potential roles.”

Historically, Russia’s military has placed less emphasis on operating in geosynchronous orbit than in low-Earth orbit or other unique perches in space. Due to their positions near the equator, geosynchronous orbits are harder to reach from Russian spaceports because of the country’s high latitude. But Russia’s potential adversaries, like the United States and Europe, rely heavily on geosynchronous satellites.

Other Russian satellites have flown near Western communications satellites in geosynchronous orbit, likely in an attempt to eavesdrop on radio transmissions.

“So it is interesting that they may be doing a GEO inspector,” the retired US military space official told Ars. “I would be curious if that’s what it is. We’ve got to watch. We’ve got to wait and see.”

If you’re a fan of spy techno-thrillers, this all might remind you of the plot from The Hunt for Red October, where a new state-of-the-art Russian submarine leaves its frigid port in Murmansk with orders to test a fictional silent propulsion system that could shake up the balance of power between the Soviet and American navies.

Just replace the unforgiving waters of the North Atlantic Ocean with an environment even more inhospitable: the vacuum of space.

A few minutes into the film, the submarine’s commander, Marko Ramius, played by Sean Connery, announces his orders to the crew. “Once more, we play our dangerous game, a game of chess, against our old adversary—the American Navy.”

Today, nearly 40 years removed from the Cold War, the old adversaries are now scheming against one another in space.

It’s hunting season in orbit as Russia’s killer satellites mystify skywatchers Read More »