Childhood and Education #9: School is Hell

This complication of tales from the world of school isn’t all negative. I don’t want to overstate the problem. School is not hell for every child all the time. Learning occasionally happens. There are great teachers and classes, and so on. Some kids really enjoy it.

School is, however, hell for many of the students quite a lot of the time, and most importantly when this happens those students are usually unable to leave.

Also, there is a deliberate ongoing effort to destroy many of the best remaining schools and programs that we have, in the name of ‘equality’ and related concerns. Schools often outright refuse to allow their best and most eager students to learn. If your school is not hell for the brightest students, they want to change that.

Welcome to the stories of primary through high school these days.

Peter Gray reports on the Tennessee Pre-K experiment, where they subjected four year olds to 5.5 hours a day of academics five times a week. Not only did the control group (kids whose parents applied and got randomly rejected, so this was effectively an unblinded RCT) catch up on academics by third grade, the control group was well ahead by sixth grade, and the treatment group had a lot more rule violations and diagnosed learning disabilities. I think Peter’s conclusion that drill in Pre-K and kindergarten is actively bad is overreach, since the dose often makes the poison, but yeah focusing on drill that early seems terrible.

NYC officials consider virtual learning to reduce class size. It seems the law requires there be no more than 20 to 25 kids in a classroom depending on grade level. So the proposed solution is to get rid of some of classrooms entirely. Transparent villains happy to inflict torture upon children.

How to organize a protest against your teacher, recommended, made me smile.

Scott Alexander asks, given Americans clearly do not know basic facts that were supposedly taught in school, but do remember things through cultural osmosis, what is even the point of school? If you learn via spaced repetition, isn’t school failing rather miserably at that? The unstated question there is if you actually wanted to teach things, wouldn’t you used spaced repetition, which schools don’t use in any systematic way. The answer to the puzzle, of course, is that school is not about learning.

Your periodic reminder: Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture according to the San Francisco Unified School District. Features of ‘white supremacy culture’ include Perfectionism, Individualism, Sense of Urgency and Objectivity. They end by saying we can do better.

A theory, from a longer thread.

David Bessis: The #1 reason why we fail to teach math: we present it as knowledge without telling kids it’s a motor skill developed by practicing unseen actions in your head. Passive listening is useless, yet we never say it. We’re basically asking kids to take notes during yoga lessons.

Math is about reconfiguring our brains and reprogramming our intuitions. By ignoring this, we effectively refuse to teach math. We teach the cryptic symbols and convoluted formulas, but we never teach the secret art of making intuitive sense of them.

I think he severely oversells it in the longer thread, but he has a good point. You learn math by doing, by messing around, by experimenting and playing. Math lectures are relatively a waste of time.

Even getting math thought at all is increasingly hard. Here’s governor Newsom, signing a law, SB 1410, explicitly to force Algebra I to be taught to eighth graders, and all he can do is require the Instructional Quality Commission to ‘consider including’ that it be offered. What happens when they consider it, and simply say no?

Florida 9th graders rebel against their Algebra 1 state exam, refuse to take it despite it being a graduation requirement, in sufficient quantities to invalidate the test.

I do not see why any test would have an attendance requirement to count? Let the half that want to take it take it now, the other half can change their minds and study for a refresher when they realize they won’t graduate without it. At least if we don’t cave.

Alternatively, if the students can simply form a union and make the school cave, let’s see what else they want to do with that power, shall we?

Even if you end up at a ‘good’ school, a 10/10 rated school, what do you get? Mostly you get a lot of wasted time.

Tracing Woodgrains: This thread is absolutely correct. Sometimes people treat “good schools” as black boxes where you put kids in and education pops out, with everything working well

But for many kids, their core memory of even “good schools” will simply be waiting idly. So much more is possible.

Simon Sarris: The schools in my town are fine. The high school has 10/10 score on GreatSchools and the others have high scores for academics

But the best public (and many private!) schools still do very little in terms of education and take up too much time. Most engaged parents could not only do more with less time, but do more interesting things, and have more help around the house as the kids grow, since they’re around much more of each day.

The curriculum at so many schools just has terribly low expectations of what a child should be learning. Looking at the english/lit curriculum here was glum. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was disappointing at “elite” colleges now, too.

I have higher expectations than that.

I went to excellent catholic schools for 12 years. I had a fine time. I liked all my teachers.

Still, my biggest childhood memory of school was just waiting. Waiting for everyone else to be done, waiting for the day to be over, waiting to be picked up. I think we can do better.

Matthew Yglesias: It’s mostly child care (for young kids) or prison (for teens) where the hope is that some learning takes place. You could teach much more efficiently but then the kids would have to go somewhere else.

Freia (QTing Lehman below): Public school isn’t just tailored to the average student, it’s designed to oppress and humiliate smarter kids with genuine curiosity and enthusiasm for learning.

Every smart kid has stories of trying to read under the desk to escape the monotony and having their book taken.

These kinds of kids are acing the exams, and unlike e.g. talking, reading under the desk bothers no one. confiscation is just punitive.

It’s hilarious that their justification is always “respect”, as if it’s not disrespectful to waste hours of kids’ lives w/ useless “teaching.”

In HS i skipped a year of math by reading a textbook & taking a placement exam. it took me ~40 hours over 10 days to teach myself the material—taking the class would have been >200 hrs. the amount of kids’ time we’re wasting is totally unconscionable.

Why does this continue to be true? One reason: A lot of people do not care about smart kids. Or they actively want them to suffer.

Charles Fain Lehman (1m views): I think we underrate how hard it is to provide education to a range of abilities at scale. If the smart kids are bored, that’s an okay outcome.

Most interventions don’t work at scale! School kind of does some stuff! That’s pretty good!

I also spent a lot of time waiting as a kid. That was good! I’m glad that I was forced to wait. It was an important lesson in how my edification is not the most important thing.

But ofc, this is exactly the fallacy. “Everyone should have their ideal outcome.” But they can’t under given constraints! The question is always how to optimize.

In other words, you.

Seriously, what the actual ?

Here’s a general response: if you think (as the qt does) that “so much more is possible,” provide me with an evidence-based intervention that a) reduces smart kids’ boredom and b) yields large increases in attainment. I’m happy to hear about them!

Okay, at least that is a form of the right question. I don’t know why it has to be ‘and’ here. If the smart kids are not bored, or it increases attainment, either one of those is super awesome on its own. So can we do either or both of these things, at scale, without actively damaging the other?

Yes. Obviously. ‘Evidence based’ requires someone collecting whatever you consider admissible evidence for your particular court, but here are some interventions that seem very very obviously like they do these things.

-

Magnet schools or tracking. Give them their own classroom with more advanced topics. Why do I even have to say this.

-

Allow grade skipping, both in individual subjects and overall. If you can pass the tests, you can move up. Obviously this will help with both issues. If you say ‘what about socialization if you aren’t stuck in classrooms with kids exactly your own age’ short of kids trying to skip 4+ years prior to high school then I will flat out piledriver you.

-

Let kids acing a class do other things when bored, and ideally skip the busywork too. This could not be simpler. If you are getting an A, and you want to read a book about something else, or do homework for another class, go ahead. If you want to be a jerk limit it to ‘educational’ things, sure, fine.

-

Let the kid stay home and learn from LLMs and textbooks, provided they keep passing your periodic tests. Seriously.

-

Let the kid take online college classes. Arizona State University’s are $25 each and some are done by children as young as 8. Others are often outright free.

There is mostly universal agreement that great teachers are much better than good teachers, who are much better than bad teachers. There is not agreement about how to find, create or enable the good and great teachers, or how to fire and avoid the bad ones.

Strangest of all, there is no agreement that we even should in theory be firing the bad teachers and hiring good ones. It’s easier said than done, but you have to say it first. There are even those who say ‘it is wrong to attempt to get your child in front of better teachers, that’s not fair,’ which is somehow not a strawman.

Noah Smith: Progressives claim test scores are about family wealth. Conservatives claim test scores are about IQ. But a lot of test scores are about the government’s ability to FIRE BAD TEACHERS AND HIRE GOOD TEACHERS.

Alz: Here’s a fun paper by a Stanford econ JMC on grade school math teachers. Looking at AMC data matched to Linkedin, paper finds that even just decent, above-average middle/high school math teachers dramatically increase students’ AMC scores: top AMC scorers increase by 165%!

The paper in question is ‘Early Mentors for Exceptional Students,’ which is a different topic than finding good teachers in general, but finds that exceptional teachers going the extra mile can massively increase the chances talented students will win honors, attend selective universities, and have the most valuable career paths. There are obvious concerns about selection effects, they did some work to minimize that but I’d still be wary.

Alex Tabarrok emphasizes that the highest marginal educational value is in mentoring the smartest and most talented kids to be all they can be. Having access to a mentor greatly increases the chance that our best talent truly excels. Roughly half of the potential top math students in the country stay unidentified. Alas, so many in education think that when exceptional students get a chance to excel further, this is at best a nice to have, and perhaps even bad because it ‘increases inequality.’

The broader point from Noah Smith is also important. If we believe teacher quality is valuable, why are we in so many ways not acting like that?

Which leads to the question, what factors predict teacher quality?

Journal of Public Economics: Just published in @JPubEcon”The unintended consequences of merit-based teacher selection: Evidence from a large-scale reform in Colombia.“

The paper examines a nationwide merit-based teacher-hiring system in Colombia that replaced experienced contract teachers with higher test-performing new teachers. The reform decreased students’ test scores and reduced college enrollment and graduation by more than 10 percent.

The paper examines the effect of a nationwide merit-based teacher-hiring system, which replaced experienced teachers with high-performing new teachers. The new teachers could choose where they would go, replacing old teachers.

From what I (read: me asking Claude questions) could tell, the policy did not in any way evaluate the teachers being replaced, or attempt to replace bad teachers rather than good teachers. The new teachers decided where to go based on what they wanted. So effectively, they were replacing either random teachers, or the teachers with more desirable assignments.

Thus, what we find here is that when we replace random existing teachers en masse with new teachers, and do so without using local knowledge and relying mostly on test scores (see Seeing Like a State) the reduction in experience and non-measured qualities overwhelmed the new teachers scoring higher on the tests.

The study goes too far when it suggests that test scores are uncorrelated with teacher quality. I don’t care what studies show here, that doesn’t make sense. But it can be one factor of many, and relying on it too much can still be actively worse than the previously used methods, as can sticking teachers into new locations they’re not familiar with, as can lack of overall experience, all at once.

If you want to do a reform like this, it has to go hand in hand with firing the bad teachers rather than random teachers, or you’re going to at least be in for a very tough transition.

It is important to realize that teachers are sometimes very wrong about basic things, and sometimes when you point this out they dig in. It is remarkable the extent to which some people refuse to believe this, and tell people that they are lying or remembering wrong.

from r/NoStupidQuestions: My son’s third grade teacher taught my son that 1 divided by O is 0. I wrote her an email to tell her that it is not 0. She then doubled down and cc’ed the principal. The principal responded saying the teacher is correct… What do I do now?

Tbh, I’m mildly infuriated but I’m wondering if I’m just overreacting? Should I just stop fighting this battle?

Andrew Hoyer: Ask them to enter 1 / 0 into a calculator and report back.

Andrew Rettek: People say this is fake, but as a high school senior I had two teachers and my principal tell me that 22/7 was irrational.

Magor: Well, pi is irrational. So every fraction with numerators and denominators that are integers is rational except for the one that’s pi.

Andrew Rettek: This was their reasoning, yes. My principal literally told me that he thought that 22/7 was the only non repeating fraction.

Elizabeth van Nostrand: One year I worked as assistant at summer school for 3rd graders. The teacher said echolocation worked because water was made of electricity, and columbus was financed by the wife of King James of Spain.

Is this a case for or against formal education? Either way, it is wise.

At any given level of education, literacy rates have fallen dramatically, despite overall literacy rates remaining unchanged. Simpson’s Paradox! But as Alex Tabarrok points out, also a scathing indictment of the educational system, pointing to both the signaling model of education and also highly expensive inflation in that signal.

Schools in many places, including Palo Alto and Alameda, increasingly refuse to allow math acceleration. They flat out don’t let kids learn math at any reasonable pace, and this is allowed to continue in areas with some of the brightest student pools around. I wouldn’t mind too much if schools simply taught other subjects to the kids instead, it’s not like being way ahead in math is ultimately all that valuable and you can learn pretty easily on the computer anyway, but they’re flat out wasting hours a week of the kid’s time.

Andrew Bunner: Our district is as Niels describes. Our daughter got in trouble for working on her outside-school advanced math during class even though she finished the worksheet they were assigned.

Neils Hoven: The audacity of a student! To try to learn something while in school.

Benjamin Riley (Former deputy attorney general of California, founder of ‘Deans for Impact,’ self-described ‘influential voice in education’): It’s so weird this keeps happening to the children of the Tech Bro community. Will no one speak for them?

Niels Hoven: This is the former deputy attorney general of California and an influential voice in education, saying that if your child is stuck doing work below their ability, then you must be a Tech Bro and your child’s learning needs don’t matter.

Gallabytes: this happened *to me*. my parents are not remotely tech bros. they tried their best, put me in schools they felt were good, and those schools thought that the best way to enrich my math education was to make me teach the other kids. this WILL NOT HAPPEN to my children.

There are very few issues I’d emigrate over. mandatory public schooling is one of them, and things like this are why.

Mason: To understand tall poppy syndrome you have to fully accept that yes, they want your children cut down to size as well.

They do not feel that they have to hide this because they do not think it’s a bad thing. They think this is prosocial.

I suppose we now know what impact those deans want to have. Their issue is education. They are against it.

Niels Hoven has other examples as well, such as this one from Justin Baeder, a former principal now training other principals. Or this from his own experience, in response to Baeder asking “what would be the point?”

Niels Hoven: It’s fascinating to see “education thoughtleaders” who are not only unable to imagine the benefits of supporting high-achieving kids, they’re unable to imagine a world where it’s even possible!

I went to public school and took AP Calculus in 8th grade. For my entire school career, I was in group classes with kids no more than 2 years older than me, with the exception of 3rd-6th grade when I would do an hour of independent study during math class.

Every day when my 4th grader comes home, he asks how my conversations with his school are going because he’s tired of being taught material he already knows.

Don’t tell me that kids don’t want to be challenged, and don’t tell me that it’s impossible for us to do so.

But yeah, Justin Baeder can do so much better.

Justin Baeder: The academic acceleration maximalists are honestly worse than the sports dads living vicariously through their kids and making them hate the sport.

Yes, you probably CAN push your kid to do 10th grade math in upper elementary school. But…why?

Of course, if you have a true prodigy and they want to go all in on something, go for it. Just recognize that you are choosing a very difficult path for your child and yourself. This is not normal or healthy parenting, and doesn’t lead anywhere your kid will want to go.

How dare you actually attempt to have your kid actually learn things? Just flat out.

But it gets even better than that, wait for it…

Justin Baeder: Let’s say your kid reads many years above grade level, as mine do and always have.

Guess what—that just means they run out of books to read faster than everyone else!

What’s the goal here? How does it benefit the child to pay $$$ to push them even farther out?

That’s right. You need to be careful. They’ll run out of books!

That’s why you need to smuggle them in.

Pamela Hobart: just another underappreciated yet tremendously brave teacher protecting an uppity 5yo from running out of books here in South Austin, what a relief.

Quoted Post: Kindergarten parents: If your child could read entering Kindergarten, are they reading in class yet?

We’ve been pretty disappointed and are curious if it is the teacher or public school.

At the beginning of the year our daughter was excited to learn but now she says she hates to read and do math. She asked the teacher to read harder books and was told “no” – this was from her teacher and her teacher justified it by saying she doesn’t know if she has comprehension yet (she does).

My daughter confirmed she read a lot in preschool and has only read once in Kindergarten (when she brought her own books from home) in school. My daughter says she doesn’t want to bring books from home anymore or read at home because her teacher hates reading. We are worried to make a big fuss because the teacher told us our daughter should be in GT and we don’t want to jeopardize that if we just have a bad teacher this year but we can’t see our daughter continue to hate learning, when she used to enjoy it.

She also just got settled with friends. And if it matters we are seeing problems in math too where the teacher is working on counting to 10 still but my daughter can add/subtract 100+ and knows some multiplication tables.

Foxyavelli: It’s somehow rare kids are being held back from learning but literally everyone who knows a smart kid in school or was that kid has an anecdote.

Faded Magnet: This happens a lot, and it’s not new. Similar happened to me as a kid, because I arrived at school already reading. I just read what I wanted at home and played along at school.

David Hines: “why are you homeschooling, David?” WELL —

Ian Miller: I tell my sister we need bad teachers because there aren’t enough good ones to meet the necessary demand. But the current crop of bad ones seem determined to prove me wrong.

How should we think about solutions that only help high achievers?

We should think of them as highly valuable. Instead, we see the opposite.

Niels Hoven: This article is typical of the toxic attitudes toward high achieving kids.

High achieving students are seen as “the kids who need it the least” as though they’re some kind of second-class citizen. If they learn quickly, it isn’t a success, it’s a problem to be solved.

So yes: A huge portion of those tasked with educating students is working to actively sabotage our best and brightest, and often the other kids too, thinking this is good and also gaslighting everyone involved about the whole process.

Kelsey Piper: Our schools are failing children. Some parents, mostly the rich ones, have the time and confidence to speak out about it. Then people go “oh it’s a whiny privileged people problem”. No. Your schools are also failing the children whose parents don’t know how to speak out.

Not that it’d be acceptable to deny kids a good education because their parents are whiny privileged people! That’d be a cruel and evil thing to do! But in fact what we’re doing is denying all kids a good education and then looking who objects.

And then going “oh it’s only the rich people who object so it’s only their kids who are being harmed so it’s fine”, which is just evil on so many different levels I can’t quite fathom it.

Entertainingly many of these same people hate private schools on the grounds that it’s bad when privileged parents opt out instead of advocating to make the schools better. damned if you do, damned if you don’t.ta

Some places used to have standards, including standards for admission, like Thomas Jefferson High School. Then they killed many such places, so RIP, with national merit semifinalists down 50% in a year despite increased class sizes. And the entire county went from 264 semifinal candidates to 191, showing that this is a real loss.

A lawsuit was allowed to go forward challenging NYC’s gifted programs as ‘segregation,’ including targeting Stuyvesant High School and Bronx Science. It asserts that testing for academic ability is ‘racial’ and discriminatory. The admission tests in question are very similar to the SAT. The whole thing is madness and an attempt at civilizational suicide. If there is a law that makes that kind of admissions test illegal, it is incompatible with civilization, and the law must be repealed.

The latest formerly exceptional school we have learned was intentionally destroyed in the name of ‘equity’ comes from Philadelphia. You see, it’s important not to ‘disadvantage’ some students, so we have to ensure we don’t accidentally give others an education, or admit more talented students over less talented ones. Same old story. Out with the old motto, ‘dare to be excellent.’ And that was for all practical purposes the end of Masterman.

The obvious answer is, then only give such programs to the high achievers. Having looked at the details here, it’s actually a relatively non-toxic version of the concern, noting that if 95% of students fail to benefit from or use such programs, then they’re not a solution for that 95%. Which would for now make them not a general solution.

And yes, that’s disappointing, although I expect rapid improvements over time. Also disappointing is to call such kids ‘those who need it the least’ as if the goal of mathematics education was to hit some minimum bar and then stop. But this article seems to stop short of making the case many ‘equity’ advocates actually make and even put into practice, that Niels is warning about here, which is to claim that the success of the best students is actively a problem to be fixed.

Ozy Brennan: a question for people concerned with educational equity: if schools aren’t flexible enough to serve children who are multiple grade levels ahead, how well do they serve children who are multiple grade levels behind? (badly. it’s badly)

I also agree, for these reasons and also for others including cultural ones, that parents should have a right to see the curricula that is being imposed by force upon their children in a public school, so they know what and how their children are learning. And that a school or teacher refusing to share this information, or the state supreme court saying you don’t get to see it is a five alarm fire. I don’t see how someone can say ‘no this is a secret, you have no right to that, and send your kids to school or we’re calling the cops’ and not notice the skulls on their uniforms.

The ultimate proof that school is not about learning is that we know school starts too early for teenagers to properly sleep and thus be ready to learn, we’ve known forever, and it is impossible to fix this.

Lomez: The dread of school could be mitigated by 75 percent by simply letting children sleep in. Teenagers need significantly more sleep; without adequate amounts, they can become depressed and irritable. When I am education czar, the children will get their sleep.

Danielle Fong: My co-founder presented a study showing that teenagers learn better if they can sleep in a little more. The school responded with, “Well, we can’t adjust it now; we have a contract with the bus drivers.”

Oh, so the school is for the benefit of the bus drivers?

Much like the port is for the benefit of the longshoremen and the polity is for the benefit of politicians, eh?

Relatedly, morning classes fail spectacularly.

Abstract: Using a natural experiment which randomized class times to students, this study reveals that enrolling in early morning classes lowers students’ course grades and the likelihood of future STEM course enrollment. There is a 79% reduction in pursuing the corresponding major and a 26% rise in choosing a lower-earning major, predominantly influenced by early morning STEM classes. To understand the mechanism, I conducted a survey of undergraduate students enrolled in an introductory course, some of whom were assigned to a 7: 30 AM section. I find evidence of a decrease in human capital accumulation and learning quality for early morning sections.

Wait, a 7: 30 AM section? What fresh hell is that? When I was in college I did sign up intentionally for 9: 00 AM classes and given my sleep schedule that turned out fine, but the other kids clearly didn’t love it. A 7: 30 AM start time is nuts, such a thing should not exist, we need to amend the Geneva Conventions.

Still, the reduction seems extreme. 79% reduction in further classes is quite a lot if this was indeed a randomized trial. I presume some of it was the cultivation of hatred and aversion rather than pure lack of human capital. At this level, the classes at that hour are effectively non-functional. How can those involved not notice this? Why would anyone ever need (or want) to schedule a class that early? How many points are these kids attempting to take?

Legal battles continue (WSJ) over whether, if you decide to have charter schools at all, also allowing religious charter schools is then mandatory or forbidden. There does not appear to be middle ground. One of these violates the first amendment, the other does not, but it is not clear which is which. If it was mandatory, in some places charter schools would get a lot more support, and in other places they would get a lot less.

I do not think the government should be discriminating here, and imposing an effectively very large tax on those who want their children to go to religious schools, or any other kind of school, provided everyone has a local non-religious public school available. And frankly, a lot of the ‘non-religious’ public schools are effectively rather (non-traditionally, de facto) religious and have no intention of knocking it off, giving me even less sympathy.

Then there’s the step beyond that, those who appose privately funded private schools. People being mad that some pay for private school while also paying for everyone’s public school will never actually stop being weird to me, as will people who think this is super commonly done by people in the upper middle class purely for quality reasons.

Quinn: there’s this class of upper-middle/upper class urban yuppie that makes a big stink out of sending their kids to “public school” and man… I hate them. Yeah, your kid will go to your decent local K-5 and bolt when shit gets real, just like every aspirational underserved family.

Matt Bruenig: Reminder when approaching this discourse that 90% of children attend public schools, most of the rest attend so-so religious schools.

If ‘shit gets real’ in my local school, and I am being underserved, I do not know what that means, but it does not sound like a time to not be bolting? Yet most people do not have that option. Also, yes, it is very strange that the same person also thinks this:

Quinn: I want to see the urban public education system completely broken down and rebuilt from the bottom up. I do not hate that it exists; I hate how it is.

Again, seems like bolting conditions to me. If you are expecting parents to sacrifice their children on the alter of public pressure to improve failing schools, please speak directly into this microphone.

Politico: School choice programs have been wildly successful under DeSantis. Now public schools might close.

Chris Freiman: Netflix has been wildly successful. Now Blockbuster locations might close.

Politico does point to some concerns. If standard schools are losing interest, why then destroy the schools that are exceptional, as many places are somehow doing? That seems rather perverse.

Hopefully the Montessori school could reconstitute itself, but the ‘vote with your feet’ plan only works if you close the schools that lose feet, not the ones that keep them.

Andrew Atterbury: One proposal aiming to turn a popular Fort Lauderdale magnet school that focuses on the Montessori teaching method into a neighborhood school brought a crowd nearing 200 people in opposition at a recent town hall. There, dozens of audience members, a sea of blue “VSY’’ shirts representing Virginia Shuman Young elementary, contended the plan would cause an unnecessary “disruption” for a top-rated school.

…

“If your product is better, you’ll be fine. The problem is, they are a relic of the past — a monopolized system where you have one option,” Chris Moya, a Florida lobbyist representing charter schools and the state’s top voucher administering organization, said of traditional public schools. “And when parents have options, they vote with their feet.”

The data cited in Politico says that the decline in enrollment due to increased homeschooling is modestly bigger than the increase in private school attendance, some of whom are getting scholarships to do it. Home school as always has principle-agent issues where you worry if the education is happening, if you do not trust parents to want to educate their children.

But yes, if you do not zero out the very high social cost of regular schooling, home schools start to look a lot better. If the city gave us a budget equal to what it costs them to have our kids in schools, I would 100% be putting together a vastly better homeschooling program with that money.

Always remember it could be so much worse.

Bryne Hobart: Discussions about school vouchers, homeschooling, etc. make me feel grateful that it’s legal for us to cook for our kids, even though neither my wife nor I went to culinary school. Things could be very different.

Microschools are an obviously great idea. The cost of private school is far in excess of the costs of hiring a teacher, renting a space and paying for plausible supply and other costs. You get the socialization benefits of school, and the flexibility and customization to not do the awful parts, and as a society we get to try different stuff.

Also, home schooling and stay-at-home parent are expensive, and now you can spread that cost around along with its benefits.

Getting rid of trivial inconveniences can help quite a lot in such cases. Instead of having to go through rezoning, the school will often find space it can use for free.

Matt Bateman: Microschools are an extremely good and natural format for schooling and the only reason they aren’t much more common is because of unnatural blockers.

“Hey maybe we should pool our children and resources around the best and most willing educator in our community” is an obvious and ancient approach to organizing schooling and it’s quite strange that we today have managed to greatly disincentivize it

Politico: Florida Republicans, led by Gov. Ron DeSantis, want to let tiny private schools open in libraries, movie theaters, churches and other spaces where they can fit makeshift classrooms.

…

Florida’s policy change appears small; it allows private schools to use existing space at places like movie theaters and churches without having to go through local governments for approval.

But it could have a dramatic impact. This shift gives these private schools access to thousands of buildings, opening the door for new education options to emerge without them having to endure potentially heavy rezoning costs.

Primer, a company poised to act as a support system for such schools, is backed by Sam Altman. The man’s past investments often have excellent taste and speak well of his values. I’d be curious what he has invested in this year, after the events of November.

Scientific American used to be a magazine my family subscribed to that contained cool articles about science. Now it is… something else.

The latest example of this is Scientific American’s hit piece on home schooling. Eric Hoel has a thread and a post detailing the situation. The part about educational results is misleading but reasonable. Then they start in on accusations of ‘abuse.’

That is the part where, after using a child that was not home schooled as justification for a moral panic, they cite a 36% rate of homeschooled children being reported for alleged abuse to show how horrible it is.

Except…

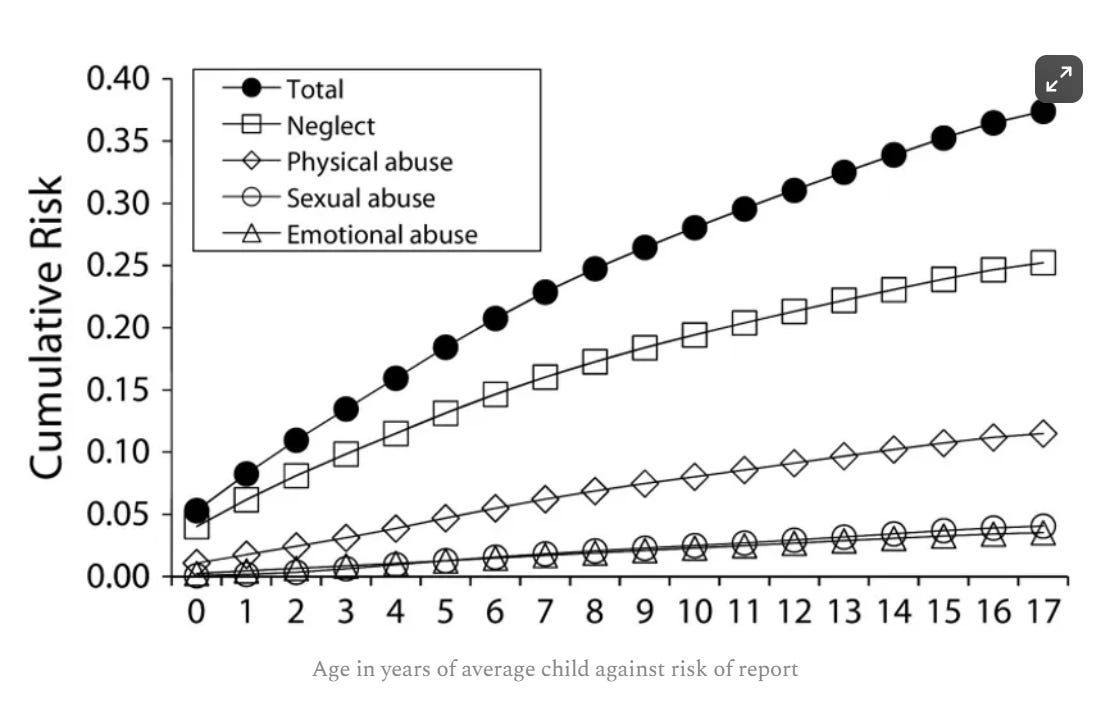

Well, it turns out researchers have an answer to that question. Here’s from a 2017 paper, “Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment Among US Children:”

We estimate that 37.4% of all children experience a child protective services investigation by age 18 years.

As Hoel notes, focusing on withdraws from school only, and other details, suggest that the base rate of abuse for home school is potentially substantially below normal. At worst, it is normal.

The good argument against home school is it requires a large investment of time and resources by the parents, so most families cannot afford to do it. Obviously, if you can get your child consistent 1-on-1 (or e.g. 4-on-1) attention and a customized path of study then that’s great, and will only get better now that AI tools are available.

Instead, the actual thesis of many against homeschooling, when they’re not making up things like the claims earlier in this section, is flat out that parents are not qualified to teach their children. And that those who claim that they could teach their own children things like how to read or write or do arithmetic are therefore ‘big mad’ and also presumably flying in the face of education and The Science.

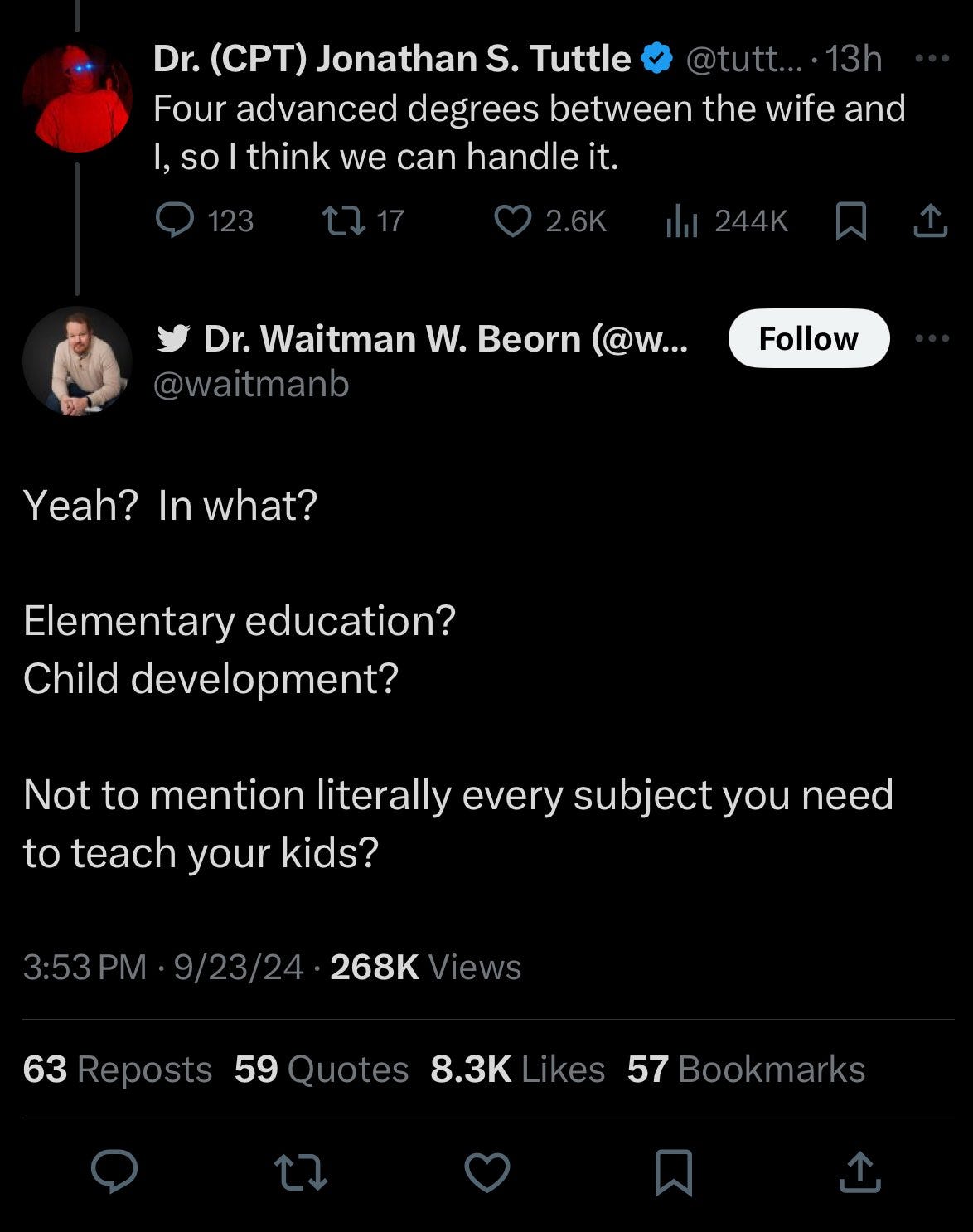

Waitman Beorn: The Home Schooling Crowd is big mad. lol But also, how insulting is it to teachers who literally train specifically to teach kids of a certain age a specific subject that Ashton and his trad wife think they can do it just as well in the playroom of their log cabin mansion?

Charles Rense: I read the replies, and they were for the most part polite and reasonable in their disagreement. The only one who’s “big mad” is you.

Polimath: How insulting to the academic institutions is it that parents with little or no training end up educating their kids better than the teachers who literally train specifically to teach kids?

Austin Allred: Anti-homeschooling folks often have expectations of school teacher qualifications that are just wildly out of touch with reality.

Jake McCoy: Dr. Waitman admitting he couldn’t teach 2nd grade math is not a great look for him.

Prince Vogelfrei: People say smug shit like this while not doing the tiniest bit of research on homeschooling outcomes which beat public schooling in every standardized test category. California makes everyone do tests, we have the data. But what does the truth matter when superiority is to be had.

Most people do not care about results, they care about process – particularly a process which ensures no one can really be blamed and avoid the messiness that ensues

It is beyond absurd to think that an average teacher, with a class of 24 kids, couldn’t be outperformed by a competent parent focusing purely on their own child. The idea that if you don’t specifically have an ‘education degree’ that you can’t teach things is to defy all of human experience and existence. Completely crazy. And yet.

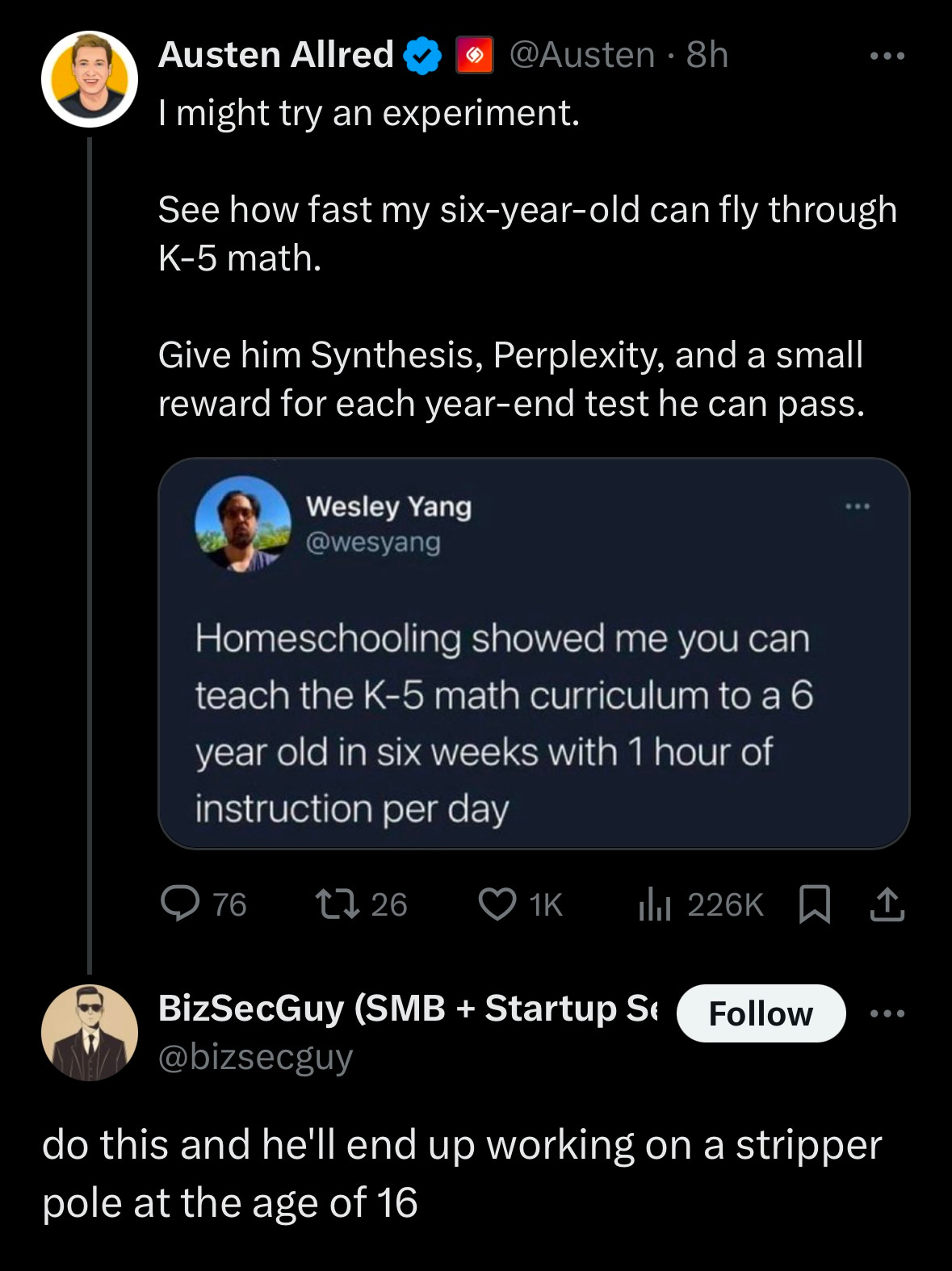

Austen Allred: The conventional view any time you dare to suggest there might be a more optimal way to learn than the existing school system.

I love that it’s a he that ends up on this hypothetical stripper pole at 16.

Kelsey Piper answers questions about her private tiny home school. Parents typically teach a weekly class, student/teacher ratio is 4:1 to 6:1, full price is $1200/month/child. All reports I’ve heard are quite good, but of course talent involved is off the charts.

Comparing the Bryan Caplan home school method to Robinson’s similar one, with critique of the general framework and focus. Both focus on not helping the student, letting them work things out, with Robinson being full on ‘the student must never be helped with any problem.’

They assigned kids two hours of math a day. I am confused why that is needed, if you train in math reasonably less than half of that should be plenty. I get that history and music are secondary priorities, but cutting them out entirely seems like a mistake, although honestly art can go. I also don’t see how most children could focus like that. I know mine would have no hope no matter how hard I tried. In general, why so much time in a chair doing school-style work? I don’t understand how that helps.

Of course all of it is obsolete now. If you have access to Gemini Pro 1.5 and Claude Opus, all previous learning techniques are going to look dumb.

The constant refrain I hear is ‘but what about socialization?’ Which seems crazy to me, and I love this way of putting it.

Violeta: Re: the socialization issue with homeschooling

I asked my 16yo daughter who went back to high-school this year “do you wanna continue next year?”

“I don’t think I’m ready for the isolation of sitting 6h with people only of my exact age and an adult speaking at us for 90% of the time, I need to socialize more.”

There are far better ways to get socialization. What socialization you do get in school, from what I can tell, is by default horribly warped in deeply unhealthy ways. Most of the value is essentially ‘you might make a friend at all, and then interact with them outside of school in your few hours of freedom.’ There are better ways to find friends.

Aella summarizes her home school experience, listing pros and cons of the type she experienced. The cons are that parents control what you learn and who you see, and your social skills and knowledge base are different from other kids. The pros are you don’t waste massive amounts of time instead learning at your own pace, you don’t get stratified by age and you dodge a lot of toxic dynamics in normal schools.

Her description of her three months in normal high school instruction, where everything is checking off a box and no one actually cares, tells you that yes it can be otherwise, we should be horrified by our defaults. If your soul has not yet been crushed and you show up most of the way through the process, the soul crushing engine becomes impossible to miss.

If you are a parent, presumably ‘choose what to teach’ is pro rather than a con, and you will choose something reasonable. So the only cons are having quirky socialization touchstones rather than the insane ones we get in primary and high school, which all mostly gets overridden anyway? Yeah, choice seems very clear if everyone involved can handle and invest in the process.

The exact opposite method is illustrated in this video, the concept of never making a child do anything they do not choose to do on their own. As several people here note, this is the ‘homeschool with no effort by doing actual nothing’ method, and by default it is absolutely be an excuse for negligence. It can also be done right, via noticing what children actually want and ensuring they find it and helping steer them, which requires work as active as other methods.

When can you teach children about law and procedure and proof? Tracing Woodgrains suggests about 8, Kelsey Piper thinks similarly.

Michael Gibson asks a good question, but the opposite might be even better?

Michael Gibson: Why do kids hate school? If you don’t have an answer to that question then you’re not even in the conversation, let alone the debate.

Rebel Educator: The tragedy inside America’s K-12 schools.

Here’s another question. Why do kids love school?

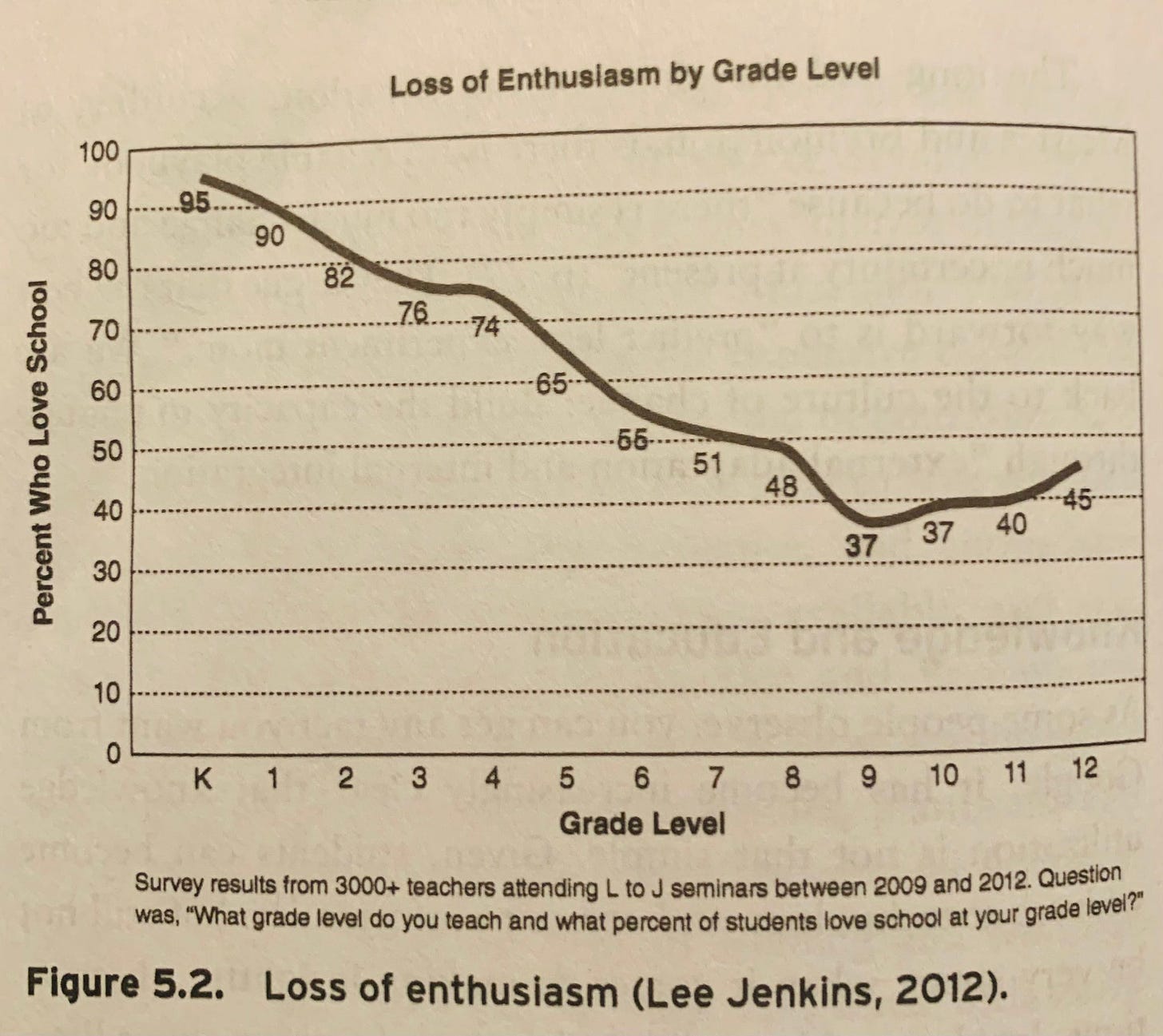

Notice that teachers are saying that 95% (!) of their kids love Kindergarten (I can’t imagine they’re paying close attention, given my anecdata and this very different poll even if its sample is biased, but perhaps normies be norming), they still believe 74% love fourth grade, and even at the trough 37% are supposedly loving Grade 9.

If you force kids into a fixed location and subject them to strict control and force them to work at arbitrary stuff for roughly half of waking hours, these would be very good rates of loving the results, if the teachers are describing the kids remotely accurately. Consider that if you ask people if they ‘love’ their job, that’s going to score rather lower. We’re doing some things very wrong, but we must also be doing some things very right.

In relative terms this reaction seems roughly right? You start out with ‘hang out with other kids and mostly do fun things,’ which plausibly kids do mostly enjoy, then they turn it into progressively more sitting still for lectures and progressively more homework and busywork and wear you down for years. Then as high school progresses you start to get a bit of flexibility back and the world lets you do things like walk on your own or select classes or do actual work, so things improve a bit.

Remember, it could be so, so much worse.

Richard Hanania: In South Korea, 84% of five year-olds and 36% of *two year-oldsattend private tutoring schools. What causes a culture to go this far off the rails? This is genuinely horrifying.

Again, not for every child all the time, even in a ‘normal’ school.

But for many children, it mostly makes them miserable while wasting their time.

And I’d boldly claim that this is not good.

And I disagree with Tracing Woods in that actually they can articulate this pretty damn well most of the time.

Tracing Woods: I hated school starting in first grade. I wanted to go faster, wanted more interesting work, wanted something better. I kept wanting this and kept leaping at any available alternative through twelfth grade. Kids can’t fully articulate their desires. But they know.

Kelsey Piper: I’m not going to say “kids are 100% accurate at identifying the best learning environment for them”. But they will absolutely tell you “I hate school” if they hate school. They will tell you by begging you to quit your job and homeschool them, by telling you it’s okay if that means the family ends up homeless, we can set up a tent in the lot on the corner. They will tell you by pretending to be sick, and by really being sick.

If they love their school, they tell you that too. They will tell you by begging you to take them in to their school on weekends. They’ll spend Christmas break complaining that school isn’t in session. They’ll say to you thoughtfully ‘I do really love my summer camp, but it makes me sad to be missing out on school’.

If you’ve decided your five or six year old is too stupid to be worth listening to, you may miss the signs they’re in a really bad situation that is harming them a lot – and you’ll definitely be teaching them that their education is not something in which they are active participants, not something where their perspective is valued, not something where their experiences even matter.

I also hear a lot of people say ‘if you let them choose, won’t they just choose whatever school is easiest and has the most toys?”. No. They won’t. One family at our microschool literally had their child do a side by side comparison by attending public school and the microschool for a period of time and then choosing where they wanted to go. The child loved the amenities that the public school offered – it had way more funding! It was big enough to have a soccer team!

But they were desperately bored. They said that everything the teacher said, they already knew. They spent all day being told to be quiet while the teacher said boring things. And they didn’t want that.

Almost everyone was supportive, with many similar stories. Then there was one person who spoke up to say that kids saying they are miserable is fine, actually.

Ed Real (Teacher): Vomitous drama queen tripe. In Kelsey’s fantasy world, people are secretly wondering “why isn’t my kid begging for me to homeschool them? What’s wrong with me?”

Kelsey Piper: I think you may have misread. I was saying that children do beg their parents to homeschool them sometimes. If your children aren’t, that’s a good thing!

Ed Real: Oh, no, I understand what you’re saying and it’s designed to get parents to worry if their kids aren’t soooooooooo engaged with their school life that they’re DEMANDING more! In fact, a kid begging for homeschool or private school or whatever needs to be squelched routinely.

Kelsey Piper: Do you think that kids are never miserable in their school environment and are only pretending to desperately seek alternatives, or do you think that they are miserable but that the correct way for parents to respond when their children are miserable is ‘squelching routinely’?

EdReal: I think your inability to distinguish between misery and a kid whining that he’s miserable is a very big part of your delusion. Absent criminal neglect or abuse, “miserable” is not the word to use about a child’s state of mind. Not seriously, anyway.

Especially since you’re claiming these kids are “miserable” for academic reasons. I mean, social reasons, bullying, sure. But academic? Please.

And yes, I’m saying you are positing such children to make other parents envious.

Scott Alexander: I was miserable at school and begged my parents to home school me. I still endorse this 30 years later, and my parents (who refused at the time) in retrospect agree. I can’t figure out if you’re denying my existence or saying that because I was a child my feelings didn’t matter.

Ed Real: Neither. I am saying that “miserable” is not an accurate description of your state of mind. You were a bright kid who felt you could do better. Oh, well. Pretty obvious you didn’t suffer career-wise.

Keller Scholl: It is always striking to me that one of the most common nightmares is being back in school, under the control of people like this poster, and this is not seen as a failure of schools.

Mike Blume: Teachers on [Twitter] doing a fucking fantastic job of making me want to entrust my children to their institutions.

Rohit: People forget their own schooling, I think. Things I did to show school was boring:

Repeatedly said school was boring.

Skipped all classes.

Created a pro and con list on why I should spend all my time in the library.

Read advanced textbooks for fun.

Not taking children seriously is wrong.

I think that if a child tells you they are miserable at school, chances are they are miserable at school. And yes, of course I speak from experience. Do people doubt that being constantly bored, for hours every day, is insufficient?

As in:

In class I’d pass the time

Drawing a slash for every time the second hand went by

A group of five

Done twelve times was a minute

ButShameika said I had potential

I mean, yes, that is pretty miserable. Stop pretending it isn’t. Or that it doesn’t matter when a particular teacher is very much not Shameika, so long as you ‘turn out okay.’

There are plenty of other reasons that school can become a five alarm fire you need to get away from (e.g. Fiona Apple also notes ‘I wasn’t afraid of the bullies and that just made the bullies worse.’) But boredom and wasted time is enough.

You can do so much more, and we should treat failure to excel where it was possible similarly to how we (should and used to but increasingly also don’t) treat failure to stay at grade level for average students.

Daniel Buck: We need to quit wasting the time of gifted students and make it easier for them skip grades.

How many spend their days twiddling their thumbs after finishing the days work in minutes, waiting for their classmates? Or worse, getting conscripted to be the teacher’s errand runner?

I actually think being the teacher’s assistant is far better than thumb twirling, especially if the thing you assist with is the actual teaching. Still not ideal.

Matt Bateman: People are so used to talking about minimum acceptable outcomes in education that they truly have no idea how high-variance educational outcomes can and should be.

The top quartile of students can skip grades. The top 2 percent of students can do an entire multiyear curriculum in *weeks*.

As Nuno Sempere says, there are obvious problems with ‘kids decide when they get to drop out of regular school.’ At minimum, there need to be highly credible costly signals sent, rather than simply expressing a preference. Kids often have to be told to do things they don’t want to do. And you want a credible signal of how much they don’t want to be there, not one designed to get them what they want.

I have a very strong commitment, that if this kind of misery around school appears and is sustained, then that is that. Especially if they successfully locate and point out this statement.

Democracy mostly works, to the extent it works, because when things are truly terrible, people get mad and then they Throw the Bums Out. Like the children miserable at school, we do not know what we need, but we know when conditions are miserable and it is time for a change.

Also it is insane how many people use the argument Kelsey Piper talks about below, and do so with a straight face. Indeed the comments contain many people condemning Kelsey Piper as bad for not sacrificing her children on some symbolic alter.

Kelsey Piper: I also get really irritated by “you should send your kids to bad public schools because people like you doing that is what makes them into good public schools”. I’m willing to make a lot of sacrifices for my community. Wronging my kids isn’t one of them.

I am happy to donate to local classrooms in need of supplies (I do make those donations). I am happy to volunteer in local classrooms if they need me. I am not happy to condemn my kids to unhappiness, and I frankly don’t think I have the right to do so.

They deserve some input into where they spend 40 hours a week and they want it to be in a safe environment with challenging academic work and individualized curriculum and support in pursuing their ambitions.

And again.

Kelsey Piper: The weirdest and most horrifying thing about the school choice discourse was the apparently universal assumption, on left and right, that the only thing that matters about schools is student population. On the left the takeaway was that by removing a child from a school you wronged the school; on the right the takeaway was that there is no hope for general improvements in education, just the hope that you can be better than other people at securing a place for your children in the schools with “high quality” children.

A lot of the families I know of that took their kids out of a local public school did so because their child wasn’t learning to read. Their child wasn’t learning to read because they needed phonics-based reading education and the school did not offer it. Now it was third grade and the child was badly behind, fed up with the whole concept of reading, had lots of bad habits around bluffing and faking it, and felt deeply ashamed of themselves. That family would have been much much better served by a school with the identical student body, but a better reading instruction program.

I talked recently to another parent whose school had a problem with parents fleeing for private schools. The principal of the school forbade students from doing ahead-of-grade-level work, including checking out ahead-of-grade-level books from the library. The problem wasn’t the student body. The problem was this rule.

Interruption to highlight that yes this is a thing. There are schools where they are very strict about not allowing students to get more of an education than they are supposed to get. No books that are too advanced. It is a crime against humanity, and I mean that.

Kelsey Piper: When I was in third grade at a public school, the teacher called up my mom to try to tell her that I would not be allowed to take advanced math, because the teacher thought it wasn’t healthy for girls to take advanced math. My mom objected and I got into advanced math, but I had a miserable year under that teacher, who kept me inside on detention every day on various pretexts (I’d never gotten in trouble before or since). The classmates were not the problem. The problem was the teacher.

When I was in tenth grade, the school inexplicably assigned a person who didn’t know Calculus to teach the Calculus class. He identified the smartest boy in the class on the first day and told that boy to teach us all. He did his best.

Another reason kids frequently struggle at school is because the school starts at 8am. Those kids would thrive at a school that started at 10am. Their parents often wish they had that option, but they don’t.

Interruption number two: Oh my yes, and this effect can be rather large.

Kelsey Piper: I understand that there’s a lot of research to the effect that peer effects on education are much more reproducible than teacher effects on education. And certainly ‘who attends the school’ predicts test scores more strongly than ‘are the teachers any good’. But I think somehow we have jumped from that to a deranged insistence that the only thing that can be good or bad about a school is the student body, which carries implicitly an insistence that schooling is fundamentally zero-sum, that there are no wins that do not come at someone else’s expense, that to desire your child be happy is to desire someone else’s child suffer.

When I say a school is bad, I mean ‘it does not teach reading’. I mean ‘it does not allow students to work ahead at their own pace’. I mean ‘the teacher was hostile to my child’. I mean ‘the teacher was sexist’ or ‘the teacher was incompetent’ or ‘the teacher was not sober’ or ‘the teacher was not familiar with the material’. Bullying and unsafety are ways a school can be bad for kids, but not only is it not the only way, in the cases I’ve run into it’s usually not even in the top three reasons why a child is miserable at school.

When I say a school is good, I mean that kids spend their time doing work that they’re bought in on, work that matters to them, work they care about, work that’s challenging and interesting. I mean that they want to be there. I mean that the adults who teach and mentor and support them are trustworthy and trusted.

Under the worldview where all we can do is shuffle student bodies, school choice is suspect, probably just another way for some people to profit at the expense of others. But under the worldview where schools vary in quality and in which traits they possess, school choice (if implemented justly) is obviously a good idea. It’s a good idea in two ways. The first is a form of accountability which isn’t about test scores. Schools where the teachers are miserable bullies will lose students to other schools that do better at hiring. Schools that don’t serve their students will lose out to ones that do.

The second advantage is that children are different from each other! Some want to start at 8am because they drive their parents nuts by being up since 5 anyway. Some need to start at 8am for their job. But some work night shifts or have late risers and job flexibility and benefit from a late start. Some kids do well in orderly quiet classrooms; some do well with hubbub and flexibility. Some kids care a lot if the school allows them to work ahead, and some don’t. School choice allows people to self-sort around what works for their child.

It’s obviously not a panacea. We know that because we’ve had school choice in various forms for a while now and I observe a distinct lack of panacea around here. Incentives to solve education only get you so far if no one knows how to solve education. The well-intentioned focus on testing introduced the most painful costly clear-cut Goodharting I’ve seen in any industry. And any system that involves parents taking action will benefit the kids with active and involved parents, and practically all processes benefit the wealthy because that’s in a very fundamental sense what wealth means.

But once you acknowledge that schools can be good or bad because of policies and teachers and curriculums, and that schools can be different in ways that make them a better or worse fit for a child, and that we’re not playing some relentlessly depressing zero-sum game where every benefit for any child is extracted from some other child, I think the question becomes “what would a good policy regime here look like?”.

One thing that I am very grateful about California is that you can just start your own school, pretty straightforwardly. There are no state fees; the legal requirements aren’t even that onerous. You and a few of your friends can get together and see if you can build something that’s good for your kids, and if it is, you can open it up to more kids. This does not just reshuffle the kids. It makes it possible to do better. And when you have an unsolved problem, like how to provide just, high quality education to every child everywhere, it’s really valuable to open up the possibility of inventing and iterating and finding something better.

And – if a child is miserable, their misery matters. If your child is miserable, you need to help them. Even if the studies show they’ll be fine as an adult, this is a human being, over whom you have power, to whom you have duties, and they do not only matter for their future trajectory. http://GreatSchools.com will not tell you whether your child’s school is good or bad for them, but your child will. Please listen.

Sarah Constantin: “surely nobody would criticize Kelsey for putting a ton of work into founding a goddamn school to make sure her kids got a good education, that’s like motherhood and apple pie”

oh no.

It is indeed literally motherhood, and a central part of it. And yet.

Many times, in many ways, they make it hell. On purpose.

Then they justify that because you need to be ready for more hell, and say that overrides everything else in life.

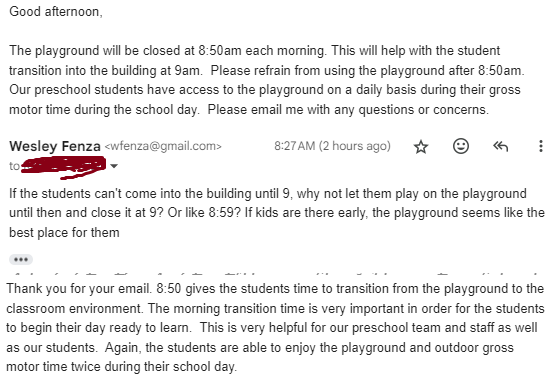

Wes: Exhibit A in why I hate school. This is from Roxie’s preschool. They don’t let the kids inside until 9am, so if they show up early, kids will often play on the playground right next to the entrance. This is now banned. The reason is “the morning transition time is very important in order for the students to begin their day ready to learn.”

This is the petty tyranny of school administrators. They have the authority to make rules, so they do whatever is most convenient for them, and always default to “don’t let the kids have any fun.” Kids enjoying themselves is seen as a threat to the educational environment. IN PRE SCHOOL. It just gets worse as the kids get older. It’s not just the kids who associating learning with being bored and uninterested – it’s the adult too. So apparently they need a ten minute “transition time” to stop having fun and get ready to go be bored in class.

Outdoor playtime is now referred to as “gross motor time” because kids can’t just play. It has to have some pedagogical purpose.

Discussion about this post

Childhood and Education #9: School is Hell Read More »