Claude Code with Opus 4.5 is so hot right now. The cool kids use it for everything.

They definitely use it for coding, often letting it write all of their code.

They also increasingly use it for everything else one can do with a computer.

Vas suggests using Claude Code as you would a mini-you/employee that lives in your computer and can do literally anything.

There’s this thread of people saying Claude Code with Opus 4.5 is AGI in various senses. I centrally don’t agree, but they definitely have a point.

If you’d like, you can use local Claude Code via Claude Desktop, documentation here. It’s a bit friendlier than the terminal and some people like it a lot more. Here is a more extensive basic discussion of setup options. The problem is the web interface still lacks some power user functions, even after some config work Daniel San misses branch management, create new repository directory via ‘new’ and import plugins from marketplaces.

If you haven’t checked Claude Code out, you need to check it out.

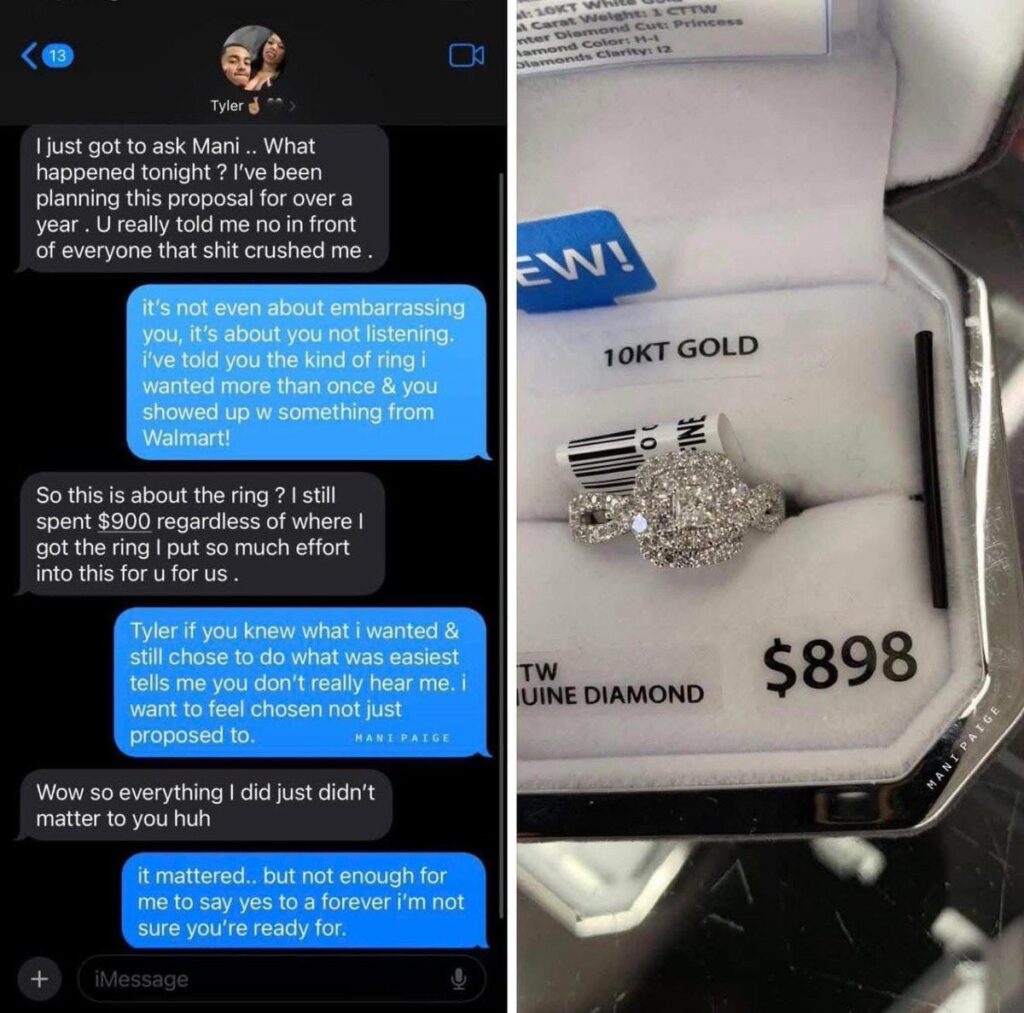

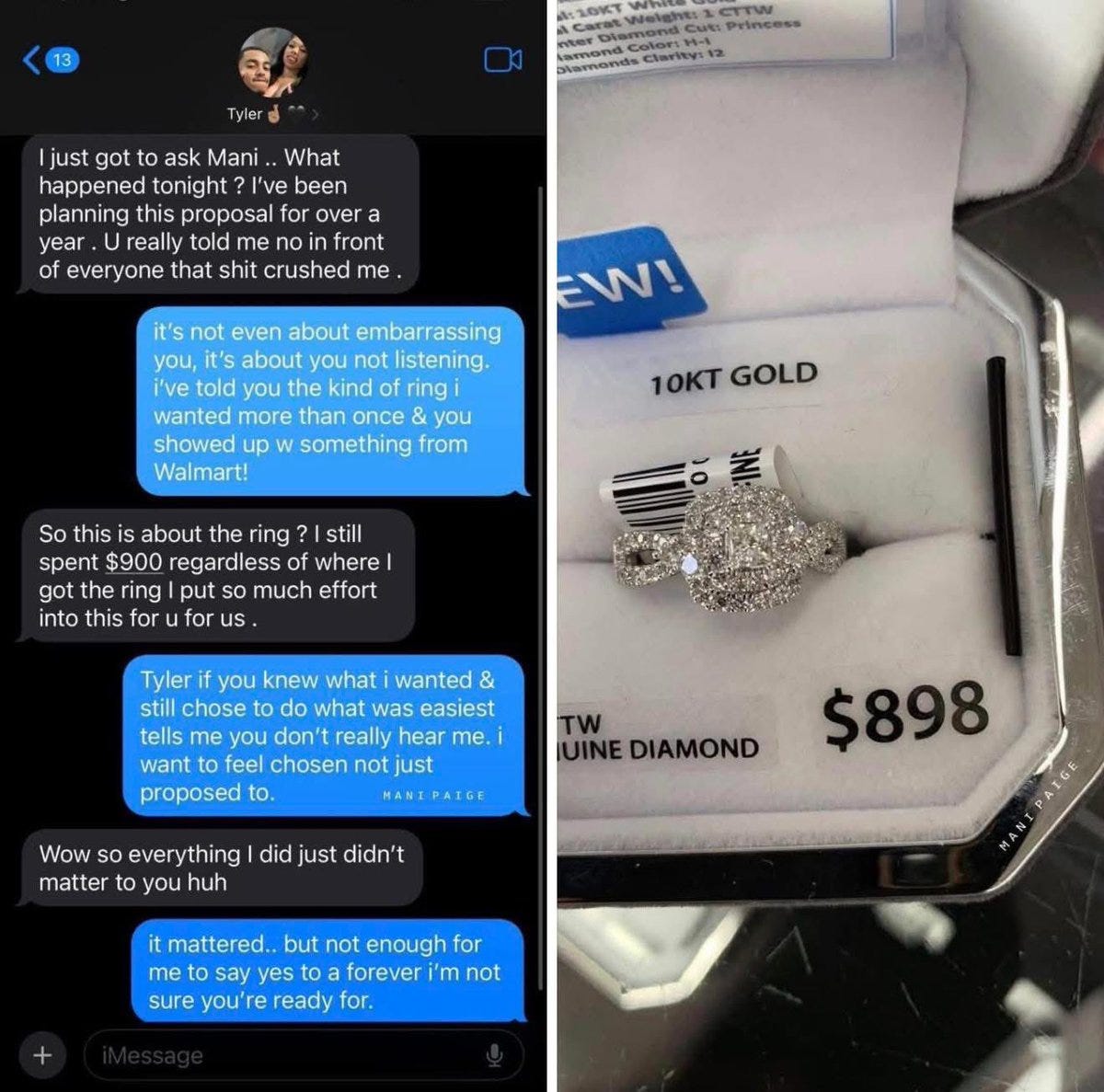

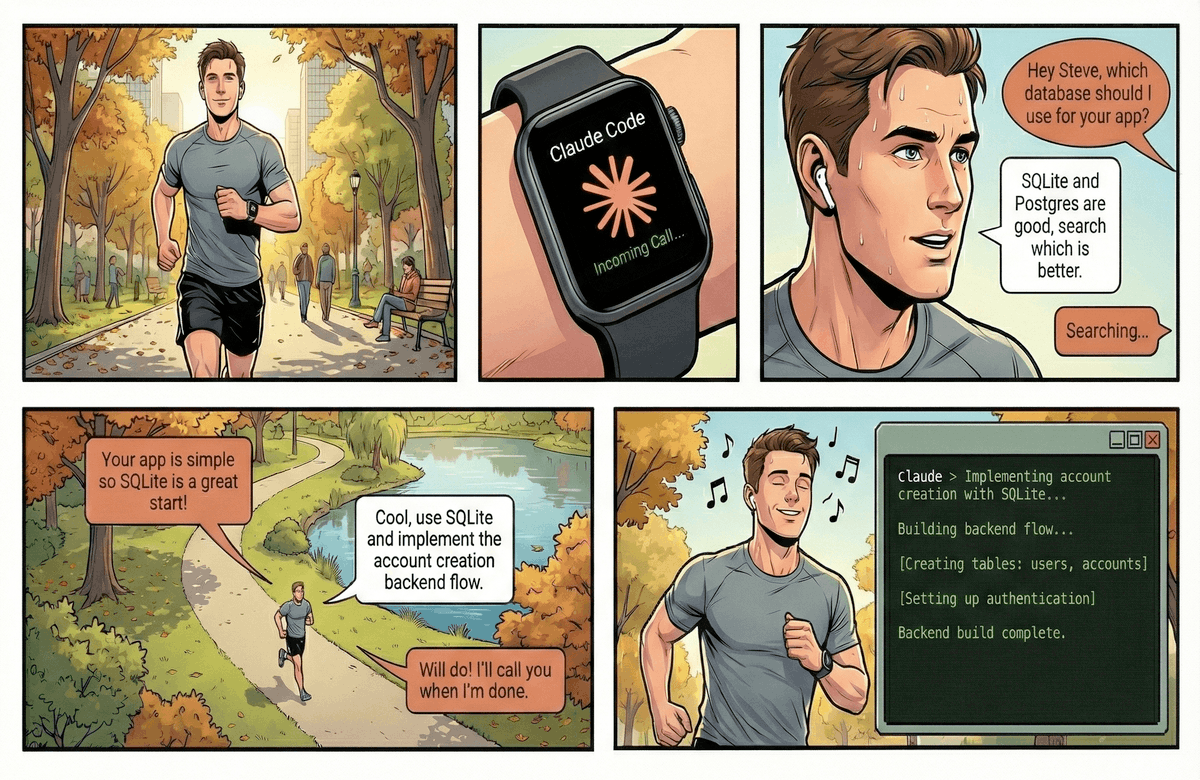

This could be you:

Paulius: whoever made this is making me FEEL SEEN

-

Hype!

-

My Own Experiences.

-

Now With More Recursive Self Improvement.

-

A Market Of One.

-

Some Examples Of People Using Claude Code Recently.

-

Dealing With Context Limits.

-

The Basic Claude Code Setup.

-

Random Claude Code Extension Examples I’ve Seen Recently.

-

Skilling Up.

-

Reasons Not To Get Overexcited.

I note that the hype has been almost entirely Claude Code in particular, skipping over OpenAI’s Codex or Google’s Jules. Claude Code with Opus 4.5 is, for now, special.

InternetVin: The more I fuck around with Claude Code, the more I feel like 2026 is the tipping point for how we interact with computers. Will never be the same again. All of this shit is becoming StarCraft for the next little bit.

Reports of productivity with Claude Code and Opus 4.5 are off the charts.

Elvis: Damn, it is so much fun to build orchestrators on top of Claude Code.

You would think the terminal would be the ultimate operator.

There is so much more alpha left to build on top of all of this. Include insane setups to have coding agents running all day.

I didn’t think it was possible to have a better experience with coding agents beyond AI-powered IDEs, then came Claude Code CLI.

Now it’s about the UIs and orchestration capabilities, and turning your computer into a 24-hour building machine. Just scratching the surface.

Rohan Anil: if I had agentic coding and particularly opus, I would have saved myself first 6 years of my work compressed into few months.

Yuchen Jin: This matches my experience. AI collapses the learning curve, and turns junior engineers into senior engineers dramatically fast.

New-hire onboarding on large codebases shrinks from months to days. What used to take hours of Googling and Stack Overflow is now a single prompt. AI is also a good mentor and pair programmer. Agency is all you need now.

Claude Code built in an hour what took a Google team a year.

That part isn’t shocking. What is shocking is that Google allows their engineers to use Claude Code instead of forcing Gemini, Gemini CLI, or Antigravity.

Jaana Dogan (Google): I’m not joking and this isn’t funny. We have been trying to build distributed agent orchestrators at Google since last year. There are various options, not everyone is aligned… I gave Claude Code a description of the problem, it generated what we built last year in an hour.

It’s not perfect and I’m iterating on it but this is where we are right now. If you are skeptical of coding agents, try it on a domain you are already an expert of. Build something complex from scratch where you can be the judge of the artifacts.

Andy Masley: Do just have the urge to post “Wow Claude + the browser app + code can just do anything with computers now and I can just sit back and watch” over and over, which imo would be annoying. Trying to not hype too much but like it does feel so crazy

Dean Ball: got tired of having Claude use my computer (mostly I use gui use for qa) so I told it to spin up a vm and hook it up to the computer use api. so now when claude needs to use the gui to test a feature it’s coding in the gui it knows to fire up its vm. this itself is agi-pilling.

Dean Ball: I agree with all this; it is why I also believe that opus 4.5 in claude code is basically AGI.

Most people barely noticed, but *it is happening.*

It’s just happening, at first, in a conceptually weird way: Anyone can now, with quite high reliability and reasonable assurances of quality, cause bespoke software engineering to occur.

Lukas: Claude code is actually as good as all the insane Silicon Valley people on your timeline are saying

It appears 80% of jobs are totally debunked and we’re just waiting for people to notice

McKay Wrigley (warning: often super excited): feels like a ton of people finally got a proper chance to toy around with cc + opus 4.5 over the holidays (aka agi for devs)

the deserved vibe shift begins.

2026 will be electric.

claude code + opus 4.5 injected the immaculate hacker vibes back into ai that we haven’t had since gpt-4.

everything is new + fun + weird again.

you can feel it.

another oom of new ideas & latent economic value is waiting to be unlocked.

and building has never been this fun.

Oliver Habryka notices he is confused, and asks why one would use Claude Code rather than Cursor, given you get all the same parallelism and access either way, so as to integrate the same model with your IDE. Henry suggests that Anthropic now RLs for the Claude Code scaffolding in particular.

My experience coding has been that when I wanted to look at the code Cursor did seem like the way unless there was some price or performance difference, but also I’ve mostly stopped looking at the code and also it does seem like the model does way better work in Claude Code.

So far I’ve been working on two coding projects. I’ve been using the terminal over the web interface on the ‘skill up at doing this before you reject it’ theory and it’s been mostly fine although I find editing my prompts annoying.

One that I’ve started this past week is the reimplementation of my Aikido handicapping system. That’s teaching me a lot about the ways in which the things I did were anti-intuitive and difficult to find and fiddly, and required really strong discipline to make them work, even if the underlying concepts were conceptually simple.

At first I thought I was making good progress, and indeed I got something that ‘kind of worked’ remarkably fast and it did an amazing job finding and downloading data sources, which used to be a ton of work for me. That would have saved me a ton of time. But ultimately enough different things went wrong that I had my ‘no you can’t straight up vibe code this one’ moment. It’s too adversarial a space and too sensitive to mistakes, and I was trying to ‘fly too close to the sun’ in terms of not holding its hand.

That’s on me. What I actually need to do is go into an old computer, find a full version of the old program including its data, and then have Claude iterate from there.

The success finding and downloading data sources was exceedingly useful. I’m still processing the implications of being able to pull in essentially any data on the internet, whenever I have the urge to do that.

I also learned some of the importance of saying ‘put that in the claude.md file.’ Finally we have a clear consistent way to tell the AI how we want it to work, or what to remember, and it just works because files work.

The more important project, where it’s working wonders, is my Chrome extension.

The main things it does, noting I’m expanding this continuously:

-

On Substack, it will generate or update a Table of Contents with working links, remove any blank sections, apply any standard links from a list you can manage, strip source info from links, or use Ctrl+Q to have Gemini reformat the current block quote or paragraph for those who refuse to use capitalization, spelling or punctuation.

-

It will copy over your Substack post to WordPress and to a Twitter Article. I’m expanding this to Google Docs but permissions are making that annoying.

-

Alt+click in Twitter Pro will add the highlighted tweet to a tab group elsewhere.

-

Alt+a on a Twitter page loads it into the clipboard, alt+v will fully paste it so that it becomes a black quote in proper format, including the link back.

-

F4 toggles between regular text and Header 4.

It’s early days, there’s tons more to do, but that already adds up fast in saving time.

I’d managed to get some of the core functionality working using Cursor, using previous LLMs, while doing a lot of reading of code and manual fixing. Annoying, although still worthwhile. But when I tried to push things further, I ran into a wall, and I ran into a wall again when I tried to use Antigravity with Gemini 3.

When I tried using Claude Code with Opus 4.5, suddenly everything started working, usually on the first or second try. What I’ve implemented is particular to my own work, but I’d say it saves me on the order of 10 minutes a day at this point, is the only reason I’m able to post my articles to Twitter, and the gains are accelerating.

Before, I had a distinct desktop, so that when I was coding with Cursor I would be able to focus and avoid distractions.

Now I do the opposite, so I can be running Claude Code in the background while I do other things, and notice when it needs a push. Vastly higher productivity.

As I write this, I have multiple windows working.

I’m having Claude Code manage my Obsidian Vault, increasingly handle my Email, it’s downloaded an archive of all my posts so I can do analysis and search easily, and so on. It seems clear the sky’s the limit once you realize it has crossed the critical thresholds.

This morning I needed contact info for someone, asked it to find it, and it pulled it from a stored Certificate of Insurance. I definitely would not have found it.

I’m still in the stage where this is net negative for my observed output, since I’m spending a bunch of time organizing and laying groundwork, but that will change.

The main reason I’m not doing more is that I’m not doing a great job thinking of things I want to do with it. That’s on me, but with time it is getting fixed.

I’m in the early stages of spinning up non-coding Claude Code folders, starting with one where I had it download a copy of all of my writing for analysis. For most basic search purposes I already got similar functionality from a GPT, but this will over time be doing more than that.

I’m not zero scared to hook it up to my primary email and let it actually do things as opposed to being read only, but the gains seem worth it.

Claude Code just upgraded to version 2.1.0, including this:

Added automatic skill hot-reload – skills created or modified in `~/.claude/skills` or `.claude/skills` are now immediately available without restarting the session

also:

Added support for MCP `list_changed` notifications, allowing MCP servers to dynamically update their available tools, prompts, and resources without requiring reconnection

Thus, if you have it create a skill for you or change an MCP server, you can now start using it without a reload.

There’s a ton of other things here too, most of them minor.

Claude Code creator Boris Cherney’s highlights are:

- Shift+enter for newlines, w/ zero setup

– Add hooks directly to agents & skills frontmatter

– Skills: forked context, hot reload, custom agent support, invoke with /

– Agents no longer stop when you deny a tool use

– Configure the model to respond in your language (eg. Japanese, Spanish)

– Wildcard support for tool permissions: eg. Bash(*-h*)

– /teleport your session to http://claude.ai/code

Fernando: Have any of these people spending thousands on CC shipped anything of note?

Jeffrey Emanuel: Yeah, I’ve shipped a tremendous amount of software in the last 8 weeks that’s used by many thousands of people.

Deepfates: Our ideas about making software need to be completely upended. You no longer have to “ship” anything. The software just needs to be useful for you. It doesn’t have to be scalable or have nine nines uptime, it doesn’t need to be a library. We are returning to the personal computer.

Peter Wildeford: People realize that Claude Code can do email and calendar right?

I do a lot of things like “Can you look at my todo list and calendars and make a plan for today” and “Bob just emailed me asking to meet, can you look at my calendar and draft a reply about when I’m available?”

You can also do things like “What are my most urgent emails?” and “What have I sent in the past two weeks that still needs a response and thus I should follow up?”

How to set this up for yourself? Just ask Claude lol.

Ankit Kumar: Claude out here replacing both my EA and my sense of guilt about unread emails.

Molly Cantillon gives us an essay on her use that Tyler Cowen expects to be one of the most important of the year, entitled The Personal Panopticon. She’s got eight main instances running at all times, it’s paying for itself in cancelled subscriptions and by managing her trades and personal finances, and so much more.

Molly Cantillon: This is the default now. The bottleneck is no longer ability. The bottleneck is activation energy: who has the nerve to try, and the stubbornness to finish. This favors new entrants.

Here’s what my tower looks like mechanically. I run a swarm of eight instances in parallel: ~/𝚗𝚘𝚡, ~/𝚖𝚎𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚌𝚜, ~/𝚎𝚖𝚊𝚒𝚕, ~/𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑, ~/𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚍𝚎𝚜, ~/𝚑𝚎𝚊𝚕𝚝𝚑, ~/𝚠𝚛𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, ~/𝚙𝚎𝚛𝚜𝚘𝚗𝚊𝚕. Each operates in isolation, spawns short-lived subagents, and exchanges context through explicit handoffs. They read and write the filesystem. When an API is absent, they operate the desktop directly, injecting mouse and keystroke events to traverse apps and browsers. 𝚌𝚊𝚏𝚏𝚎𝚒𝚗𝚊𝚝𝚎 -𝚒 keeps the system awake on runs, in airports, while I sleep. On completion, it texts me; I reply to the checkpoint and continue. All thought traces logged and artifacted for recursive self-improvement.

The essay was presumably written by Claude, does that make it and the whole process involved more impressive or less?

Roon: vessels for Claude. I don’t mean to single this person out but she wrote a wall of egregiously recognizable claudeslop about how claude is running her entire life. the Borg is coming

Near: i would be less upset if these ppl didnt lie when you ask them who wrote it

She does indeed deny it but admits it would be surprising if she hadn’t:

I do not think this is ‘one of the most important essays of the year’ and expect a hell of a year, but if you need this kind of kick to see what the baby can do and have some ideas, then it’s pretty strong for that.

Pedram.md has Opus 4.5 build an orchestrator, expecting it to fail. It succeeds.

Zulali has Claude Code recover corrupted wedding footage.

Ryan Singer is teaching it technical spaing and breadboarding, from his Shape Up methodology, it’s a technique to design features abstractly using places, affordances and wires before coding starts.

Ryan McEntush creates BuildList 2.0, a website listing companies doing important work, in two days with Claude Code. As per usual with websites, nothing here seems hard once you have the concepts down, but speed kills.

Avery vibe coded an interactive particle playground where you move them using your hands. Emily Lambert also did something similar.

Jake Eaton gives Claude Code the raw data for his PhD, the calculating and writing up of which took him 3 months the first time, and it recreates a third of the whole thing in 20 minutes with a short prompt. When you look at exactly what it did nothing is particularly impressive, but think of the time I save.

If you want Claude to use Chrome, you now have at least three options: The official Claude Chrome extension, Chrome DevTools MCP and Playright MCP. I am partial to typing ‘claude —chrome.’

You can do quite a lot with that, if you trust the process:

Nader Dabit: Claude Code can also control your browser.

It uses your login and session state, so Claude can access anything you’re already logged into without API keys or OAuth setup.

Here are 10 workflows that I’ve been experimenting with:

“open the PR preview, click through every link, report any 404s”

“watch me do this workflow once, then do it 50 more times”

“check my calendar for tomorrow’s meetings and draft prep notes in a google doc” (you can even combine this with notion pages and other docs etc..)

“open this airtable base and update the status column based on this spreadsheet”

triage gmail without touching gmail: “delete all promo emails from the last 24 hours”

scrape docs from a site → analyze them → generate code from what you learned → commit. one prompt.

“pull pricing and features from these 5 similar products, save to csv, analyze where we’re underpriced or overpriced, and draft a slide for monday’s meeting with recommendations”

“read through this notion wiki and find everywhere we mention the old API”

“compare staging vs prod and screenshot any differences”

You can debug user issues by having Claude literally reproduce their steps

If claude hits a captcha or login, it pauses, you handle it, tell it to continue, and it picks up where it left off.

It’s fun to watch chrome move in real time, no headless mode. It kind of feels like pair programming with a very fast ghost who never gets tired of clicking.

You can run this by upgrading to the latest and running claude –chrome

Use Claude Code with Chrome to directly fight customer service and file an FCC claim. When more people are doing this we’re going to have Levels of Friction issues.

Mehul Mohan points out that ideally many of us would have Claude Code running 24/7, in the background, doing various forms of work or research for potential use later. That wouldn’t be cheap, but it could well be cheap compared to the cost of your time, once you get it working well.

One issue Claude Code users share is compaction.

When you hit auto-compact, Claude Code does its best to condense the prior conversation and keep going, but you will lose important context. Daniel San disabled auto-compaction for this reason, instead choosing to restart sessions if and when limits get hit.

Many replied with some form of the claim that if you ever hit auto-compaction it means you did not manage your hooks, commands and subagents correctly.

My experience is that, at minimum, when you get into the danger zone you want to ‘rescue’ important context into files.

Daniel Sen also shares his other configuration settings.

Boris Cherny, creator of Claude Code, shows us how he uses it.

He calls his setup ‘basic.’ So yes, to many this now counts as basic:

-

Five Claude Code windows inside Terminal tabs, plus 5-10 on claude.ai/code, all in parallel, always using Opus 4.5 with Thinking.

-

I note that I do NOT use tabs for my different terminals because I want to watch the tabs work, also this is why we have three huge monitors.

-

He often will tag @.claude on coworkers’ PRs to add to claude.md. Most sessions start in plan mode.

-

He uses slash commands for every ‘inner loop’ he does repeatedly.

-

He uses some regular subagents.

-

He uses PostToolUse.

-

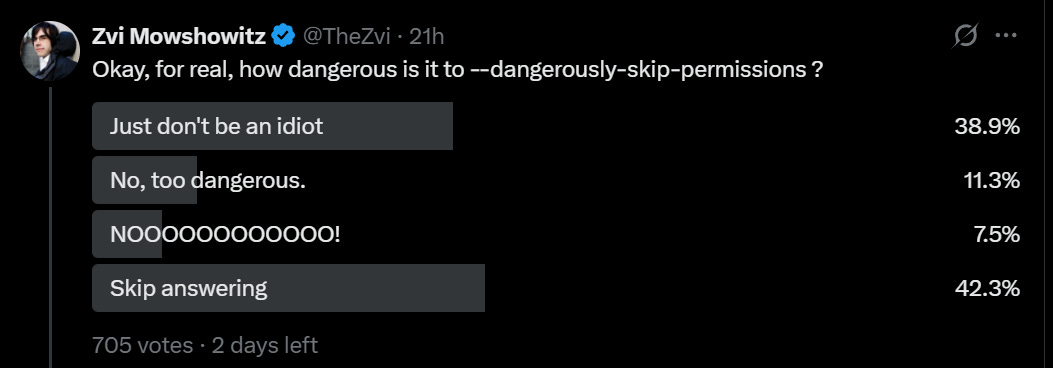

He does NOT use —dangerously-skip-permission, but does use /permissions to pre-allow common bash commands he knows are safe.

-

“Claude Code uses all my tools for me. It often searches and posts to Slack (via the MCP server), runs BigQuery queries to answer analytics questions (using bq CLI), grabs error logs from Sentry, etc. The Slack MCP configuration is checked into our .mcp.json and shared with the team.”

-

“For very long-running tasks, I will either (a) prompt Claude to verify its work with a background agent when it’s done, (b) use an agent Stop hook to do that more deterministically, or (c) use the ralph-wiggum plugin (originally dreamt up by @GeoffreyHuntley). I will also use either –permission-mode=dontAsk or –dangerously-skip-permissions in a sandbox to avoid permission prompts for the session, so Claude can cook without being blocked on me.

-

A final tip: probably the most important thing to get great results out of Claude Code — give Claude a way to verify its work. If Claude has that feedback loop, it will 2-3x the quality of the final result.

Claude Code team gives us their code-simplifier agent:

Boris Cherny: We just open sourced the code-simplifier agent we use on the Claude Code team.

Try it: claude plugin install code-simplifier

Or from within a session:

/plugin marketplace update claude-plugins-official

/plugin install code-simplifier

Ask Claude to use the code simplifier agent at the end of a long coding session, or to clean up complex PRs. Let us know what you think!

Claude Canvas gives Claude an external ‘monitor’ space for the user to see things.

Claude Code Docs tells Claude about itself so it can suggest its own upgrades, he suggests most value comes from finding new hooks.

CallMe lets you talk to Claude Code on the phone, and have it ping you when it needs your feedback.

That’s not how I roll at all, but different strokes, you know?

Claude HUD shows you better info: Remaining context, currently executing tools and subagents, and claude’s to-do list progress.

Jarrod Watts (explaining how to install HUD if you want that):

Add the marketplace

/plugin marketplace add jarrodwatts/claude-hud

· Install the plugin

/plugin install claude-hud

· Configure the statusline

/claude-hud:setup

Or have it do a skill itself, such as here where Riley Brown asks it to hook itself up to Nana Banana, so it does. Or you can grab that skill here, if you’d prefer.

Claude Code is a blank canvas. Skill and configuration very clearly matter a lot.

So, how does one improve, whether you’re coding or doing other things entirely?

Robert Long asks for the best guides. The only piece of useful advice was to follow the Claude Code team itself, as in Boris Cherny and Ado. There is clearly lots of good stuff there, but that’s not very systematic.

Ado offers a guide to getting started and to the most powerful features. Here are some:

-

If you’re importing a project, start with /init.

-

Tell claude “Update Claude.md: [new instructions].”

-

Use commands like @src/auth.ts, or @src/components, to add to context.

-

Use @mcp:github and similar to enable/disable MCP servers.

-

! [bash command] runs the command.

-

Double Esc rewinds.

-

Ctrl+R searches your past prompts and cycles matches, enter runs it, tab edits.

-

Ctrl+S stashes the current prompt.

-

Alt+P switches models (not that I’ve ever wanted to do this).

-

claude —continue or claude —resume to restore a past session.

-

/rename the current session, then refer to it by name.

-

claude —teleport to move sections between web and terminal.

-

/export dumps your entire conversation to markdown.

-

/vim unlocks vim-style editing of prompts, not being able to do normal editing is the main disadvantage for me so far of the terminal interface

-

/statusline to customize the status bar at the bottom, including things people build extensions to display, especially context window percentage

-

/context to tell you what’s eating up your context window.

-

/usage to see your usage limits.

-

ultrathink (to start a command) to get it to think really hard.

-

Shift+Tab twice to enter Plan mode.

-

/sandbox defines boundaries.

-

claude —dangerously-skip-permissions, of course, skips all permissions. In theory this means it can do arbitrary damage if not isolated.

-

/hooks or editing .claude/settings.json creates shell commands to run on predetermined lifecycles.

-

/plugin install my-setup

-

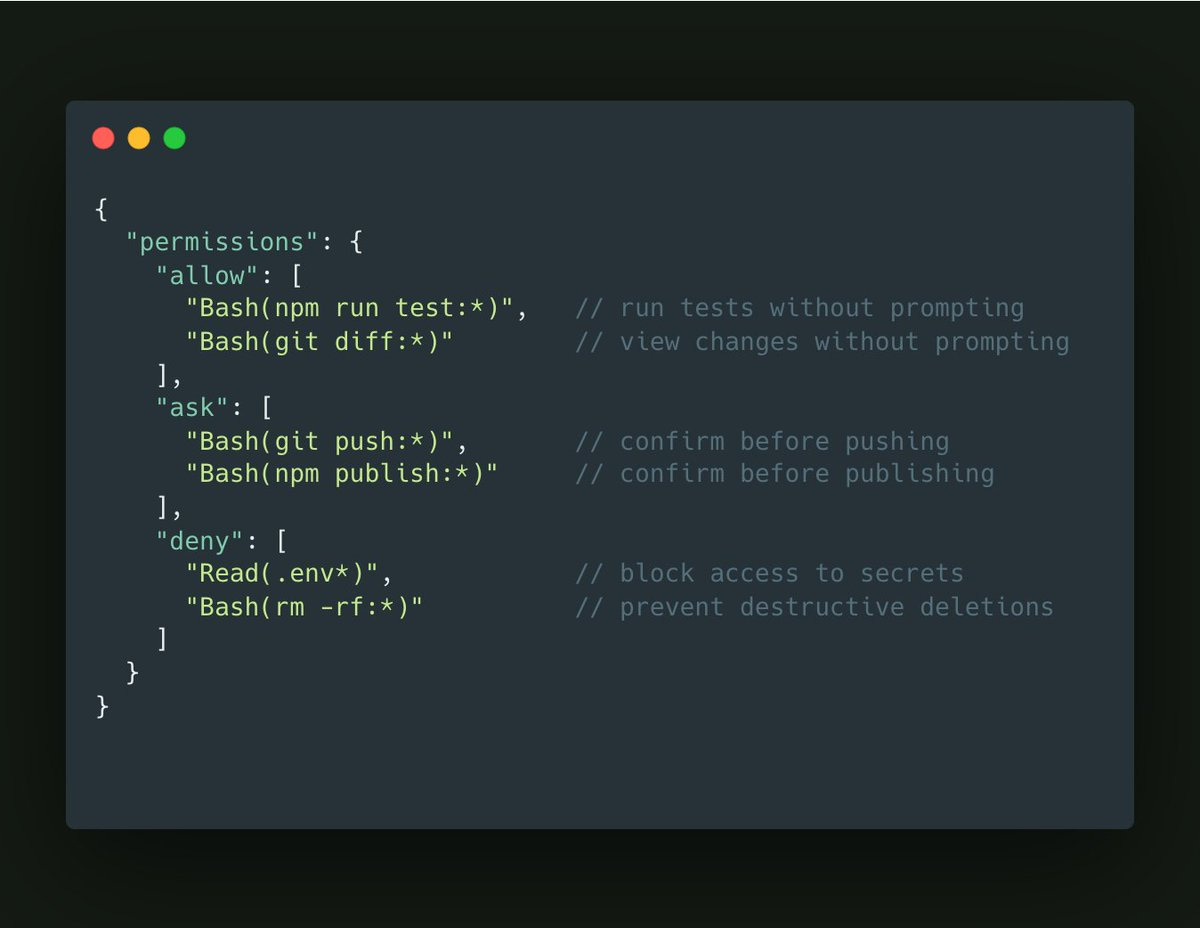

Your permissions config file has three levels: Allow, ask and deny.

Petr Baudis suggests allowing most commands with notably rare exceptions.

ask Bash –cmd ‘/brmb/’

ask Bash –cmd ‘/bgitb/’

ask Bash –cmd ‘/bcurlb/’

allow Bash –cmd ‘*’

A version of this seems logical for most uses, if you assume the system isn’t actively trying to work around you? Most of the things that go really wrong involve rm, git or curl, but also prompting on every git is going to get old fast.

My Twitter public mostly was fine with flat out dangerously skipping permissions for personal use:

Here’s a ‘Twitter slop’ style article about vibe coding that still has good core basic info. The key insight here is that it’s not about coding, it’s about communication, and specifying exactly what you want your code to do, as if you’re telling someone completely unfamiliar with your context, and having it do this one concrete step at a time and testing those steps as you go.

The process Elena is describing here should work great for ‘build something simple for your own use’ but very obviously won’t work for bigger projects.

Similar good basic advice from Dave Karsten is ‘treat it exactly as you would a junior employee you are giving these instructions to.’

Dan McAteer gives a super basic first two minute guide for non-coders.

Nader Dabit here gives a low-level guide to building agents with the Claude Agent SDK, listed partly for utility but largely to contrast it with ‘tell Claude Code to do it.’

Some people use voice dictation and have ditched keyboards. This seems crazy to me, but they swear by it, and it is at least an option.

Anthony Morris suggests you throw caution to the wind in the sense that you should stop micromanaging, delegate to the AIs, run a lot of instances and if it messes up just run it again. This is presumably The Way once you’re used to it, if you are conserving tokens aggressively on things that don’t scale you are presumably doing it wrong given what your time costs versus what tokens cost.

Another basic piece of advice is, whatever you want, ask for it, because you might well get it that way.

Allen: Is there anyway to chain skills or commands together in claude code?

Boris Cherny: Yes, just ask claude to invoke skill 1, then skill 2, then skill 3, in natural language. Or ask it to use parallel subagents to invoke the skills in parallel. Then if you want, put that all in a skill.

You can use /config to set your output style to Default, Explanatory or Learning, where Learning has it prompt you to write code sometimes. You can also create your own custom style.

Like my attempt to reimplement Aikido, when you iterate in detail in domains you know well, you see the ways in which you can’t fully trust the results or feedback, and when you need precision in any non-standard way you need to specify your requirements extremely precisely.

Noam Brown: I vibecoded an open-source poker river solver over the holiday break. The code is 100% written by Codex, and I also made a version with Claude Code to compare.

Overall these tools allowed me to iterate much faster in a domain I know well. But I also felt I couldn’t fully trust them. They’d make mistakes and encounter bugs, but rather than acknowledging it they’d often think it wasn’t a big deal or, on occasion, just straight up try to gaslight me into thinking nothing is wrong.

In one memorable debugging session with Claude Code I asked it, as a sanity check, what the expected value would be of an “always fold” strategy when the player has $100 in the pot. It told me that according to its algorithm, the EV was -$93. When I pointed out how strange that was, hoping it would realize on its own that there’s a bug, it reassured me that $93 was close to $100 so it was probably fine. (Once I prompted it to specifically consider blockers as a potential issue, it acknowledged that the algorithm indeed wasn’t accounting for them properly.) Codex was not much better on this, and ran into its own set of (interestingly) distinct bugs and algorithmic mistakes that I had to carefully work through. Fortunately, I was able to work through these because I’m an expert on poker solvers, but I don’t think there are many other people that could have succeeded at making this solver by using AI coding tools.

The most frustrating experience was making a GUI. After a dozen back-and-forths, neither Codex nor Claude Code were able to make the frontend I requested, though Claude Code’s was at least prettier. I’m inexperienced at frontend, so perhaps what I was asking for simply wasn’t possible, but if that was the case then I wish they would have *toldme it was difficult or impossible instead of repeatedly making broken implementations or things I didn’t request. It highlighted to me how there’s still a big difference between working with a human teammate and working with an AI.

After the initial implementations were complete and debugged, I asked Codex and Claude Code to create optimized C++ versions. On this, Codex did surprisingly well. Its C++ version was 6x faster than Claude Code’s (even after multiple iterations of prompting for further optimizations). Codex’s optimizations still weren’t as good as what I could make, but then again I spent 6 years of PhD making poker bots. Overall, I thought Codex did an impressive job on this.

My final request was asking the AIs if they could come up with novel algorithms that could solve NLTH rivers even faster. Neither succeeded at this, which was not surprising. LLMs are getting better quickly, but developing novel algorithms for this sort of thing is a months-long research project for a human expert. LLMs aren’t at that level yet.

Got this DM:

I appreciate that you posted this – increasingly my twitter feed feels out of whack, especially with people claiming Claude Code makes them 1000000x more efficient. Felt like I was going crazy and falling behind badly even though I use coding assistants quite a bit.

Rituraj: Twitter is a feed of “Hello World” speedruns, not Production Engineering.

Jeffrey Emanuel: As a counterpoint, I honestly feel like I’m single-handedly outproducing companies with 1,000+ developers with my 9 Claude Max accounts and 4 GPT Pro accounts.

Another danger is that a lot of the things that ‘feel productive’ might not be.

Nabeel S. Qureshi: I love that people are getting into Claude Code for non-coding use cases but some of it feels Roam Research / note-taking app coded Organizing Mac folders or getting an LLM to churn through notes feels like you’re “doing something” but is not actually producing anything valuable

Also, getting AI to read books for you and give you a summary can feel good but it’s a bit like consuming all of your food in smoothie form

The really important stuff you need to read properly, in original form, and digest slowly; this process cannot be skipped

Ben Springwater: 90% of posts on X seem to be PKM-style creating systems for systems’ sake. I have a fairly simple life, so I suppose I’m not the right persona for heavyweight personal data management systems, but I’ve seen very few use cases that seem actually useful as opposed to just demonstrating “what’s possible”.

On books, I would say that a book that ‘deserves to be a book’ can’t be summarized by an AI, and the ones ‘worth reading’ have to be read slowly or you don’t get the point, but you have limited time and can read almost zero percent of all books, and a lot of books that people discuss or get influenced by do not fall into either category.

As in, for any given non-fiction book, it will mostly fall into one of five categories. A very similar set of rules applies to papers.

-

Reading this (or some sections of this) for real is valuable, interesting on every page, you could easily write a full book review as part of that process.

-

Reading this is fun, if you summarize it you’re missing the whole point.

-

The value is in particular facts, the AI can extract those for you.

-

There’s a good blog post worth of value in there, the AI can extract it for you.

-

There isn’t even a good blog post of value in there.

So you need to know which one you are dealing with, and respond accordingly.

On organizing your notes or files, or otherwise trying to set yourself up for better productivity, that may or may not be a good use of time. At minimum it is a good excuse to skill up your use of Claude Code and other similar things.

Seriously, get pretty excited. Claude Code might not be the best tool for you, or for any particular job, but it’s rapidly becoming unacceptable to only use chatbots, or only use chatbots and Cursor-like IDEs.

Things are escalating quickly. Don’t get left behind.