A century of hair samples proves leaded gas ban worked

Science also produced a hero in this saga: Caltech geochemist Clair Patterson. Along with George Tilton, Patterson developed a lead-dating method and used it to calculate the age of the Earth (4.55 billion years), based on analysis of the Canton Diablo meteorite. And he soon became a leading advocate for banning leaded gasoline and the “leaded solder” used in canned foods. This put Patterson at odds with some powerful industry lobbies, for which he paid a professional price.

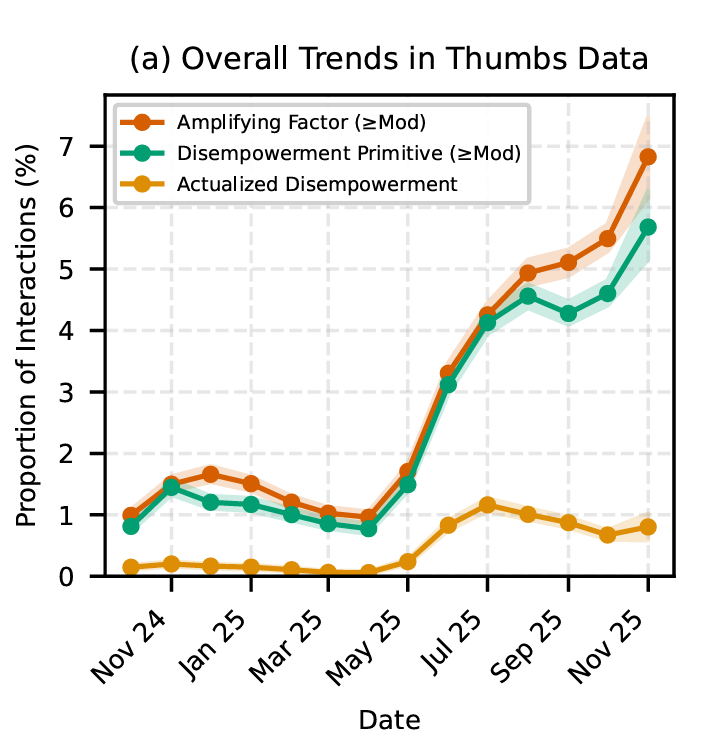

But his many experimental findings on the extent of lead contamination and its toxic effects ultimately led to the rapid phase-out of lead in all standard automotive gasolines. Prior to the EPA’s actions in the 1970s, most gasolines contained about 2 grams of lead per gallon, which quickly adds up to nearly 2 pounds of lead released via automotive exhaust into the environment, per person, every year.

The proof is in our hair

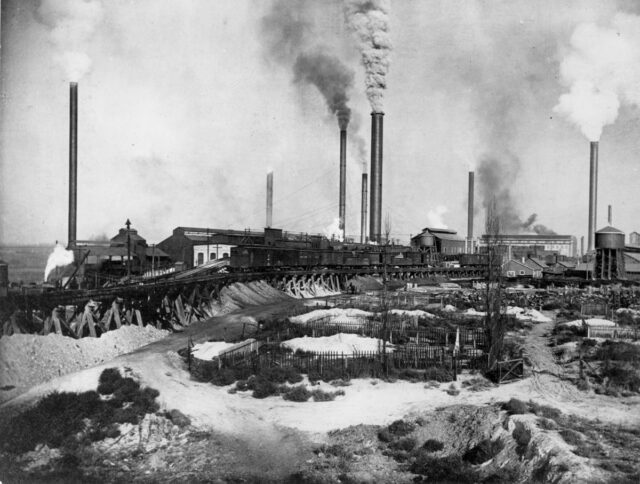

The US Mining and Smelting Co. plant in Midvale, Utah, 1906. Credit: Utah Historical Society

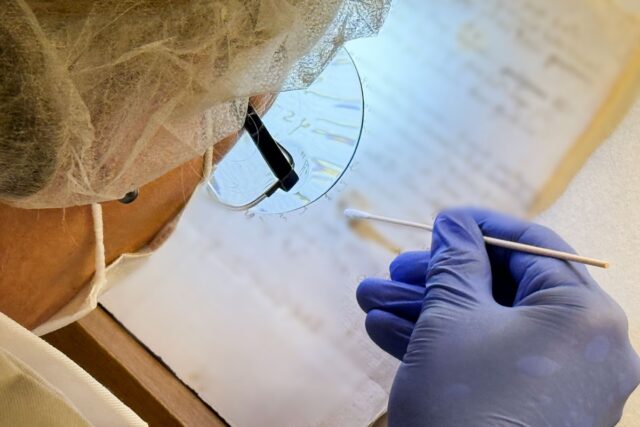

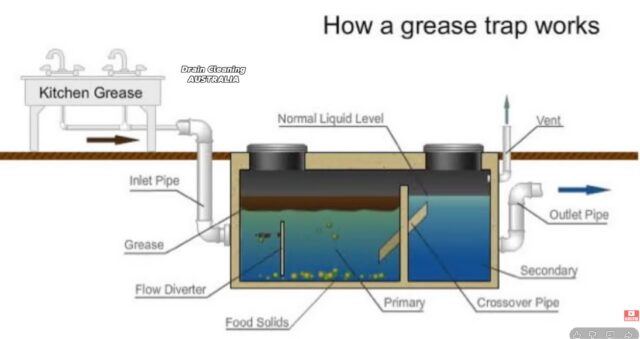

Lead can linger in the air for several days, contaminating one’s lungs, accumulating in living tissue, and being absorbed by one’s hair. Cerling had previously developed techniques to determine where animals lived and their diet by analyzing hair and teeth. Those methods proved ideal for analyzing hair samples from Utah residents who had previously participated in an earlier study that sampled their blood.

The subjects supplied hair samples both from today and when they were very young; some were even able to provide hair preserved in family scrapbooks that had belonged to their ancestors. The Utah population is well-suited for such a study because the cities of Midvale and Murray were home to a vibrant smelting industry through most of the 20th century; most other smelters in the region closed down in the 1970s when the EPA cracked down on using lead in consumer products.

A century of hair samples proves leaded gas ban worked Read More »