FCC’s import ban on the best new drones starts today

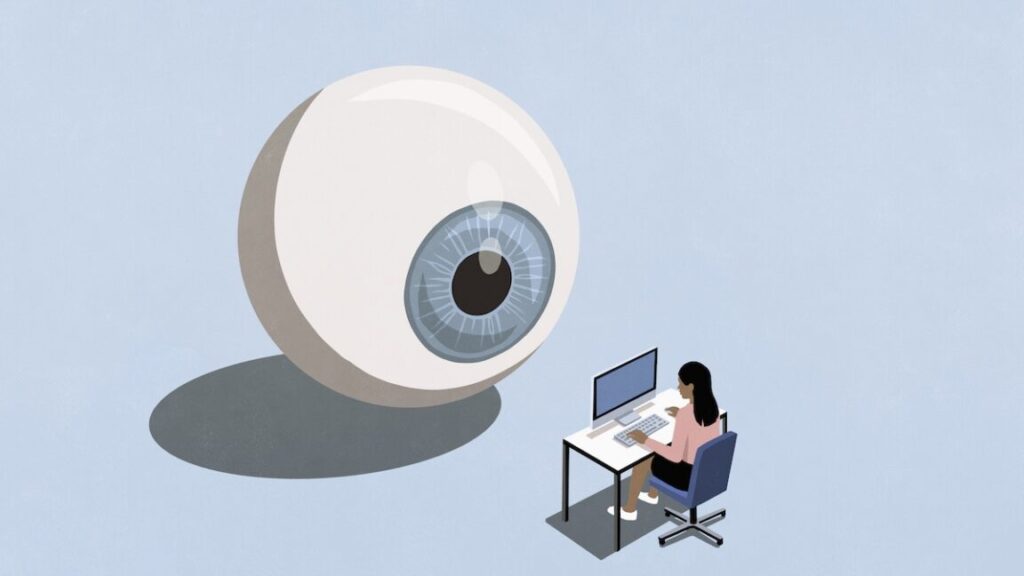

DJI sent numerous requests to the US government to audit its devices in hopes of avoiding a ban, but the federal ban was ultimately enacted based on previously acquired information, The New York Times reported this week.

The news means that Americans will miss out on new drone models from DJI, which owns 70 percent of the global drone market in 2023, per Drone Industry Insights, and is widely regarded as the premium drone maker. People can still buy drones from US companies, but American drones have a lackluster reputation compared to drones from DJI and other Chinese companies, such as Autel. US-made drones also have a reputation for being expensive, usually costing significantly more than their Chinese counterparts. DaCoda Bartels, COO of FlyGuys, which helps commercial drone pilots find work, told the Times that US drones are also “half as good.”

There’s also concern among hobbyists that the ban will hinder their ability to procure drone parts, potentially affecting the repairability of approved drones and DIY projects.

US-based drone companies, meanwhile, are optimistic about gaining business in an industry where it has historically been hard to compete against Chinese brands. It’s also possible that the ban will just result in a decline in US drone purchases.

In a statement, Michael Robbins, president and CEO of the Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), which includes US drone companies like Skydio as members, said the ban “will truly unleash American drone dominance” and that the US cannot “risk… dependence” on China for drones.

“By prioritizing trusted technology and resilient supply chains, the FCC’s action will accelerate innovation, enhance system security, and ensure the US drone industry expands rather than remaining under foreign control,” Robbins said.

Understandably, DJI is “disappointed” by the FCC’s decision, it said in a statement issued on Monday, adding:

While DJI was not singled out, no information has been released regarding what information was used by the Executive Branch in reaching its determination. Concerns about DJI’s data security have not been grounded in evidence and instead reflect protectionism, contrary to the principles of an open market.

FCC’s import ban on the best new drones starts today Read More »