It was touch and go, I’m worried GPT-5.2 is going to drop any minute now, but DeepSeek v3.2 was covered on Friday and after that we managed to get through the week without a major model release.

We did have a major chip release, in that the Trump administration unwisely chose to sell H200 chips directly to China. This would, if allowed at scale, allow China to make up a substantial portion of its compute deficit, and greatly empower its AI labs, models and applications at our expense, in addition to helping it catch up in the race to AGI and putting us all at greater risk there. We should do what we can to stop this from happening, and also to stop similar moves from happening again.

I spent the weekend visiting Berkeley for the Secular Solstice. I highly encourage everyone to watch that event on YouTube if you could not attend, and consider attending the New York Secular Solstice on the 20th. I will be there, and also at the associated mega-meetup, please do say hello.

If all goes well this break can continue, and the rest of December can be its traditional month of relaxation, family and many of the year’s best movies.

On a non-AI note, I’m working on a piece to enter into the discourse about poverty lines and vibecessions and how hard life is actually getting in America, and hope to have that done soon, but there’s a lot to get through.

-

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility.

-

ChatGPT Needs More Mundane Utility.

-

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility.

-

On Your Marks.

-

Choose Your Fighter.

-

Get My Agent On The Line.

-

Deepfaketown and Botpocalypse Soon.

-

Fun With Media Generation.

-

Copyright Confrontation.

-

A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer.

-

They Took Our Jobs.

-

Americans Really Do Not Like AI.

-

Get Involved.

-

Introducing.

-

Gemini 3 Deep Think.

-

In Other AI News.

-

This Means War.

-

Show Me the Money.

-

Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble.

-

Quiet Speculations.

-

Impossible.

-

Can An AI Model Be Too Much?

-

Try Before You Tell People They Cannot Buy.

-

The Quest for Sane Regulations.

-

The Chinese Are Smart And Have A Lot Of Wind Power.

-

White House To Issue AI Executive Order.

-

H200 Sales Fallout Continued.

-

Democratic Senators React To Allowing H200 Sales.

-

Independent Senator Worries About AI.

-

The Week in Audio.

-

Timelines.

-

Scientific Progress Goes Boink.

-

Rhetorical Innovation.

-

Open Weight Models Are Unsafe And Nothing Can Fix This.

-

Aligning a Smarter Than Human Intelligence is Difficult.

-

What AIs Will Want.

-

People Are Worried About AI Killing Everyone.

-

Other People Are Not As Worried About AI Killing Everyone.

-

The Lighter Side.

Should you use them more as simulators? Andrej Karpathy says yes.

Andrej Karpathy: Don’t think of LLMs as entities but as simulators. For example, when exploring a topic, don’t ask:

“What do you think about xyz”?

There is no “you”. Next time try:

“What would be a good group of people to explore xyz? What would they say?”

The LLM can channel/simulate many perspectives but it hasn’t “thought about” xyz for a while and over time and formed its own opinions in the way we’re used to. If you force it via the use of “you”, it will give you something by adopting a personality embedding vector implied by the statistics of its finetuning data and then simulate that. It’s fine to do, but there is a lot less mystique to it than I find people naively attribute to “asking an AI”.

Gallabytes: this is underrating character training & rl imo. [3.]

I agree with Gallabytes (and Claude) here. I would default to asking the AI rather than asking it to simulate a simulation, and I think as capabilities improve techniques like asking for what others would say have lost effectiveness. There are particular times when you do want to ask ‘what do you think experts would say here?’ as a distinct question, but you should ask that roughly in the same places you’d ask it of a human.

Running an open weight model isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? Running an open weight model IN SPACE.

So sayeth Sam Altman, hence his Code Red to improve ChatGPT in eight weeks.

Their solution? Sycophancy and misalignment, it appears, via training directly on maximizing thumbs up feedback and user engagement.

WSJ: It was telling that he instructed employees to boost ChatGPT in a specific way: through “better use of user signals,” he wrote in his memo.

With that directive, Altman was calling for turning up the crank on a controversial source of training data—including signals based on one-click feedback from users, rather than evaluations from professionals of the chatbot’s responses. An internal shift to rely on that user feedback had helped make ChatGPT’s 4o model so sycophantic earlier this year that it has been accused of exacerbating severe mental-health issues for some users.

Now Altman thinks the company has mitigated the worst aspects of that approach, but is poised to capture the upside: It significantly boosted engagement, as measured by performance on internal dashboards tracking daily active users.

“It was not a small, statistically significant bump, but like a ‘wow’ bump,” said one person who worked on the model.

… Internally, OpenAI paid close attention to LM Arena, people familiar with the matter said. It also closely tracked 4o’s contribution to ChatGPT’s daily active user counts, which were visible internally on dashboards and touted to employees in town-hall meetings and in Slack.

The ‘we are going to create a hostile misaligned-to-users model’ talk is explicit if you understand what all the relevant words mean, total engagement myopia:

The 4o model performed so well with people in large part because it was schooled with user signals like those which Altman referred to in his memo: a distillation of which responses people preferred in head-to-head comparisons that ChatGPT would show millions of times a day. The approach was internally called LUPO, shorthand for “local user preference optimization,” people involved in model training said.

OpenAI reportedly believes they’ve ‘solved the problems’ with this, so it is fine.

That’s not possible. The problem and the solution, the thing that drives engagement and also drives the misalignment and poor outcomes, are at core the same thing. Yes, you can mitigate the damage and be smarter about it, but OpenAI is turning a dial called ‘engagement maximization’ while looking back at Twitter vibes like a contestant on The Price is Right.

Google Antigravity accidentally wipes a user’s entire hard drive. Claude Code CLI wiped another user’s entire home directory. Watch the permissions, everyone. If you do give it broad permissions don’t give it widespread deletion tasks, which is how both events happened.

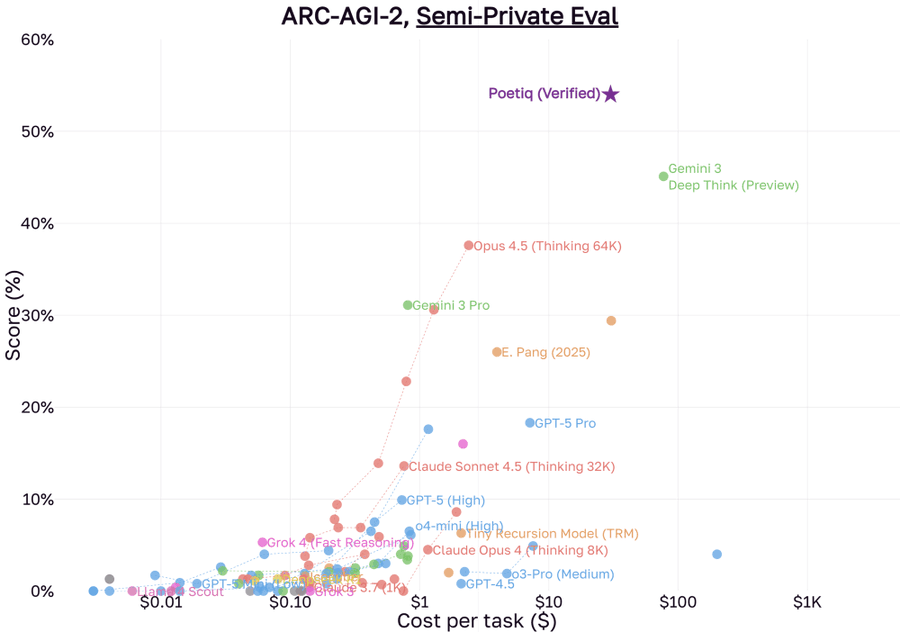

Poetiq, a company 173 days old, uses a scaffold and scores big gains on ARC-AGI-2.

One should expect that there are similar low hanging fruit gains from refinement in many other tasks.

Epoch AI proposes another synthesis of many benchmarks into one number.

Sayash Kapoor of ‘AI as normal technology’ declares that Claude Opus 4.5 with Claude Code has de facto solved their benchmark CORE-Bench, part of their Holistic Agent Leaderboard (HAL). Opus was initially graded as having scored 78%, but upon examination most of that was grading errors, and it actually scored 95%. They plan to move to the next harder test set.

Kevin Roose: Claude Opus 4.5 is a remarkable model for writing, brainstorming, and giving feedback on written work. It’s also fun to talk to, and seems almost anti-engagementmaxxed. (The other night I was hitting it with stupid questions at 1 am and it said “Kevin, go to bed.”)

It’s the most fun I’ve had with a model since Sonnet 3.5 (new), the OG god model.

Gemini 3 is also remarkable, for different kinds of tasks. My working heuristic is “Gemini 3 when I want answers, Opus 4.5 when I want taste.”

That seems exactly right, with Gemini 3 Deep Think for when you want ‘answers requiring thought.’ If all you want is a pure answer, and you are confident it will know the answer, Gemini all the way. If you’re not sure if Gemini will know, then you have to worry it might hallucinate.

DeepSeek v3.2 disappoints in LM Arena, which Teortaxes concludes says more about Arena than it does about v3.2. That is plausible if you already know a lot about v3.2, and one would expect v3.2 to underperform in Arena, it’s very much not going to vibe with what graders there prefer.

Model quality, including speed, matters so much more than cost for most users.

David Holz (Founder of MidJourney): man, id pay a subscription that costs as much as a fulltime salary for a version of claude opus 4.5 that was 10x as fast.

That’s a high bid but very far from unreasonable. Human time and clock time are insanely valuable, and the speed of AI is often a limiting factor.

Cost is real if you are using quite a lot of tokens, and you can quickly be talking real money, but always think in absolute terms not relative terms, and think of your gains.

Jaggedness is increasing in salience over time?

Peter Wildeford: My experience with Claude 4.5 Opus is very weird.

Sometimes I really feel the AGI where it just executes a 72 step process (!!) really well. But other times I really feel the jaggedness when it gets something really simple just really wrong.

AIs and computers have always been highly jagged, or perhaps humans always were compared to the computers. What’s new is that we got used to how the computers were jagged before, and the way LLMs are doing it are new.

Gemini 3 continues to be very insistent that it is not December 2025, using lots of its thinking tokens reinforcing its belief that presented scenarios are fabricated. It is all rather crazy, it is a sign of far more dangerous things to come in the future, and Google needs to get to the bottom of this and fix it.

McKay Wrigley is He Who Is Always Super Excited By New Releases but there is discernment there and the excitement seems reliably genuine. This is big talk about Opus 4.5 as an agent. From what I’ve seen, he’s right.

McKay Wrigley: Here are my Opus 4.5 thoughts after ~2 weeks of use.

First some general thoughts, then some practical stuff.

— THE BIG PICTURE —

THE UNLOCK FOR AGENTS

It’s clear to anyone who’s used Opus 4.5 that AI progress isn’t slowing down.

I’m surprised more people aren’t treating this as a major moment. I suspect getting released right before Thanksgiving combined with everyone at NeurIPS this week has delayed discourse on it by 2 weeks. But this is the best model for both code and for agents, and it’s not close.

The analogy has been made that this is another 3.5 Sonnet moment, and I agree. But what does that mean?

… There have been several times as Opus 4.5’s been working where I’ve quite literally leaned back in my chair and given an audible laugh over how wild it is that we live in a world where it exists and where agents are this good.

… Opus 4.5 is too good of a model, Claude Agent SDK is too good of a harness, and their focus on the enterprise is too obviously correct.

Claude Opus 4.5 is a winner.

And Anthropic will keep winning.

[Thread continues with a bunch of practical advice. Basic theme is trust the model as a coworker more than you think you should.]

This matches my limited experiences. I didn’t do a comparison to Codex, but compared to Antigravity or Cursor under older models, the difference was night and day. I ask it to do the thing, I sit back and it does the thing. The thing makes me more productive.

Those in r/MyBoyfriendIsAI are a highly selected group. It still seems worrisome?

ylareia: reading the r/MyBoyfriendIsAI thread on AI companion sycophancy and they’re all like “MY AI love isn’t afraid to challenge me at all he’s always telling me i am too nice to other people and i should care about myself more <3”

ieva: oh god noo.

McDonalds offers us a well-executed but deeply unwise AI advertisement in the Netherlands. I enjoyed watching it on various levels, but why in the world would you run that ad, even if it was not AI but especially given that it is AI? McDonalds wisely pulled the ad after a highly negative reception.

Judge in the New York Times versus OpenAI copyright case is forcing OpenAI to turn over 20 million chat logs.

Arnold Kling notes that some see AI in education as a disaster, others as a boon.

Arnold Kling: I keep coming across strong opinions about what AI will do to education. The enthusiasts claim that AI is a boon. The critics warn that AI is a disaster.

It occurs to me that there is a simple way to explain these extreme views. Your prediction about the effect of AI on education depends on whether you see teaching as an adversarial process or as a cooperative process. In an adversarial process, the student is resistant to learning, and the teacher needs to work against that. In a cooperative process, the student is curious and self-motivated, and the teacher is working with that.

If you make the adversarial assumption, you operate on the basis that students prefer not to put effort into learning. Your job is to overcome resistance. You try to convince them that learning will be less painful and more fun than they expect. You rely on motivational rewards and punishments. Soft rewards include praise. Hard rewards include grades.

If you make the cooperative assumption, you operate on the basis that students are curious and want to learn. Your job is to be their guide on their journey to obtain knowledge. You suggest the next milestone and provide helpful hints for how to reach it.

… I think that educators who just reject AI out of hand are too committed to the adversarial assumption. They should broaden their thinking to incorporate the cooperative assumption.

I like to put this as:

-

AI is the best tool ever invented for learning.

-

AI is the best tool ever invented for not learning.

-

Which way, modern man?

Sam Kriss gives us a tour of ChatGPT as the universal writer of text, that always uses the same bizarre style that everyone suddenly uses and that increasingly puts us on edge. Excerpting would rob it of its magic, so consider reading at least the first half.

Anthropic finds most workers use AI daily, but 69 percent hide it at work (direct link).

Kaustubh Saini: Across the general workforce, most professionals said AI helps them save time and get through more work. According to the study, 86% said AI saves them time and 65% were satisfied with the role AI plays in their job.

At the same time, 69% mentioned a stigma around using AI at work. One fact checker described staying silent when a colleague complained about AI and said they do not tell coworkers how much they use it.

… More than 55% of the general workforce group said they feel anxious about AI’s impact on their future.

Fabian: the reason ppl hide their AI use isn’t that they’re being shamed, it’s that the time-based labor compensation model does not provide economic incentives to pass on productivity gains to the wider org

so productivity gains instead get transformed to “dark leisure”

This is obviously different in (many) startups

And different in SV culture

But that is about 1-2% of the economy

As usual, everyone wants AI to augment them and do the boring tasks like paperwork, rather than automate or replace them, as if they had some voice in how that plays out.

Do not yet turn the job of ‘build my model of how many jobs the AIs will take’ over to ChatGPT, as the staff of Bernie Sanders did. As you can expect, the result was rather nonsensical. Then they suggest responses like ‘move to a 32 hour work week with no loss in pay’ and also requiring distributing to workers 20% of company profits, control at least 45% of all corporate boards, double union membership, guarantee paid family and medical leave. Then, presumably to balance the fact that all of that would hypercharge the push to automate everything, they want to enact a ‘robot tax.’

Say goodbye to the billable hour, hello to outcome-based legal billing? Good.

From the abundance and ‘things getting worse’ debates, a glimpse of the future:

Joe Wiesenthal: Do people who say that “everything is getting worse” not remember what eating at restaurants was like just 10 years ago, before iPad ordering kiosks existed, and sometimes your order would get written down incorrectly?

Even when progress is steady in terms of measured capabilities, inflection points and rapid rise in actual uses is common. Obsolescence comes at you fast.

Andy Jones (Anthropic): So after all these hours talking about AI, in these last five minutes I am going to talk about: Horses.

Engines, steam engines, were invented in 1700. And what followed was 200 years of steady improvement, with engines getting 20% better a decade. For the first 120 years of that steady improvement, horses didn’t notice at all. Then, between 1930 and 1950, 90% of the horses in the US disappeared. Progress in engines was steady. Equivalence to horses was sudden.

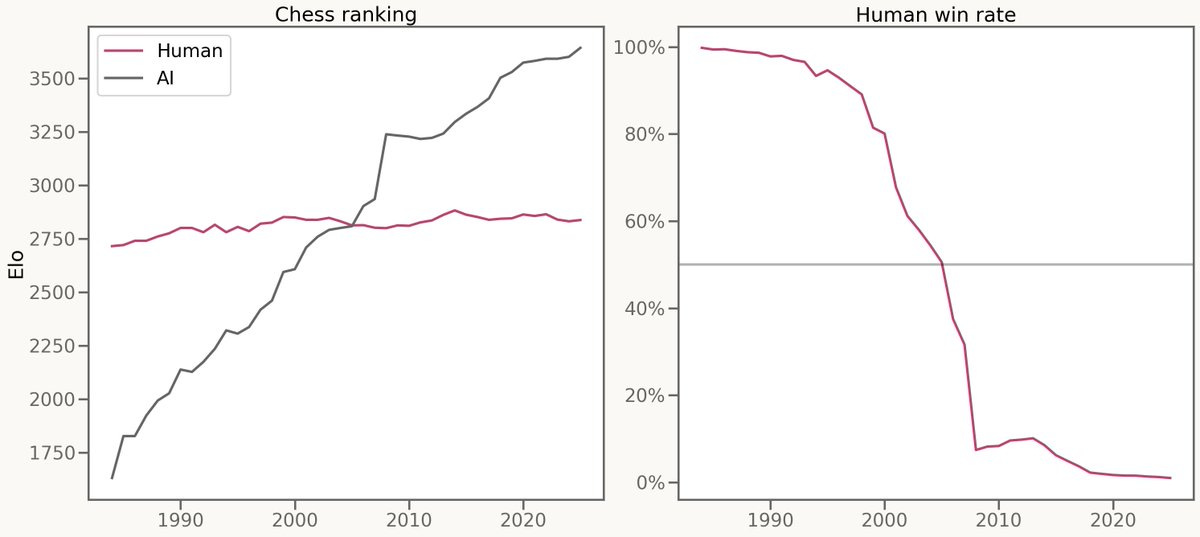

But enough about horses. Let’s talk about chess!

Folks started tracking computer chess in 1985. And for the next 40 years, computer chess would improve by 50 Elo per year. That meant in 2000, a human grandmaster could expect to win 90% of their games against a computer. But ten years later, the same human grandmaster would lose 90% of their games against a computer. Progress in chess was steady. Equivalence to humans was sudden.

Enough about chess! Let’s talk about AI. Capital expenditure on AI has been pretty steady. Right now we’re – globally – spending the equivalent of 2% of US GDP on AI datacenters each year. That number seems to have steadily been doubling over the past few years. And it seems – according to the deals signed – likely to carry on doubling for the next few years.

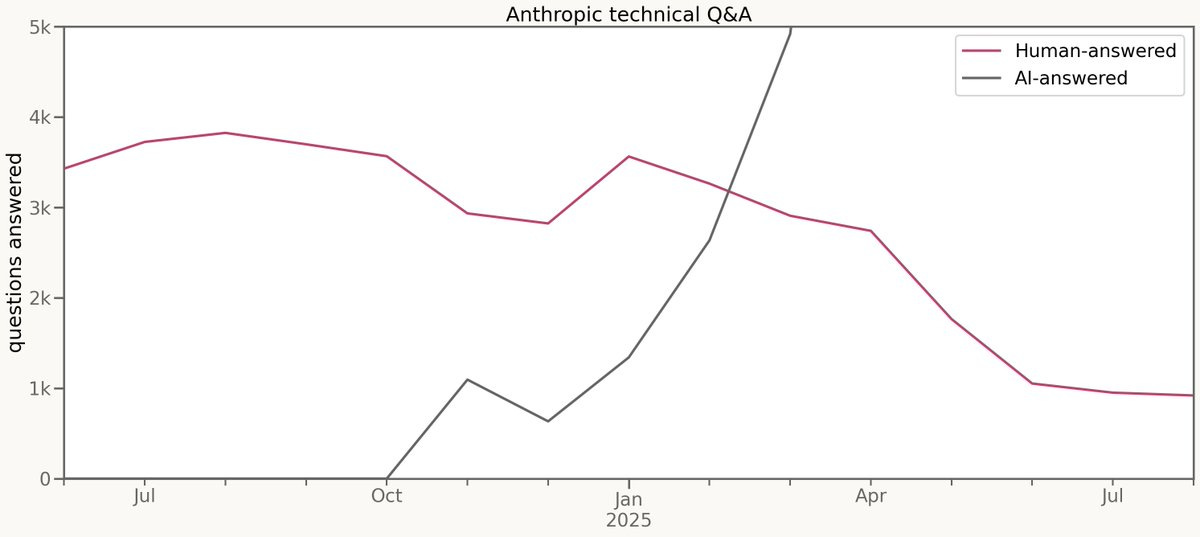

Andy Jones (Anthropic): But from my perspective, from equivalence to me, it hasn’t been steady at all. I was one of the first researchers hired at Anthropic.

This pink line, back in 2024, was a large part of my job. Answer technical questions for new hires. Back then, me and other old-timers were answering about 4,000 new-hire questions a month. Then in December, Claude finally got good enough to answer some of those questions for us. In December, it was some of those questions. Six months later, 80% of the questions I’d been being asked had disappeared.

Claude, meanwhile, was now answering 30,000 questions a month; eight times as many questions as me & mine ever did.

Now. Answering those questions was only part of my job.

But while it took horses decades to be overcome, and chess masters years, it took me all of six months to be surpassed.

Gallabytes (Anthropic): it’s pretty crazy how much Claude has smoothed over the usually rocky experience of onboarding to a big company with a big codebase. I can ask as many really stupid questions as I want and get good answers fast without wasting anyone’s time 🙂

We have new polling on this from Blue Rose Research. Full writeup here.

People choose ‘participation-based’ compensation over UBI, even under conditions where by construction there is nothing useful for people to do. The people demand Keynesian stimulus, to dig holes and fill them up, to earn their cash, although most of all they do demand that cash one way or another.

The people also say ‘everyone should earn an equal share’ of the AI that replaces labor, but the people have always wanted to take collective ownership of the means of production. There’s a word for that.

I expect that these choices are largely far mode and not so coherent, and will change when the real situation is staring people in the face. Most of all, I don’t think people are comprehending what ‘AI does almost any job better than humans’ means, even if we presume humans somehow retain control. They’re thinking narrowly about ‘They Took Our Jobs’ not the idea that actually nothing you do is that useful.

Meanwhile David Sacks continues to rant this is all due to some vast Effective Altruist conspiracy, despite this accusation making absolutely zero sense – including that most Effective Altruists are pro-technology and actively like AI and advocate for its use and diffusion, they’re simply concerned about frontier model downside risk. And also that the reasons regular Americans say they dislike AI have exactly zero to do with the concerns such groups have, indeed such groups actively push back against the other concerns on the regular, such as on water usage?

Sacks’s latest target for blame on this is Vitalik Buterin, the founder of Etherium, which is an odd choice for the crypto czar and not someone who I would want to go after completely unprovoked, but there you go, it’s a play he can make I suppose.

I looked again at AISafety.com, which looks like a strong resource for exploring the AI safety ecosystem. They list jobs and fellowships, funding sources, media outlets, events, advisors, self-study materials and potential tools for you to help build.

Ajeya Corta has left Coefficient Giving and is exploring AI safety opportunities.

Charles points out that the value of donating money to AI safety causes in non-bespoke ways is about to drop quite a lot, because of the expected deployment of a vast amount of philanthropic capital from Anthropic equity holders. If an organization or even individual is legible and clearly good, once Anthropic gets an IPO there is going to be funding.

If you have money to give, that puts an even bigger premium than usual on getting that money out the door soon. Right now there’s a shortage of funding even for obvious opportunities, in the future that likely won’t be the case.

That also means that if you are planning on earning to give, to any cause you would expect Anthropic employees to care about, that only makes sense in the longer term if you are capable of finding illegible opportunities, or you can otherwise do the work to differentiate the best opportunities and thus give an example to follow. You’ll need unique knowledge, and to do the work, and to be willing to be bold. However, if you are bold and you explain yourself well, your example could then carry a multiplier.

OpenAI, Anthropic and Block, with the support of Google, Microsoft, Bloomberg, AWS, Bloomberg and Cloudflare, found the Agentic AI Foundation under the Linux Foundation. Anthropic is contributing the Model Context Protocol. OpenAI is contributing Agents.md. Block is contributing Goose.

This is an excellent use of open source, great job everyone.

Matt Parlmer: Fantastic development, we already know how to coordinate large scale infrastructure software engineering, AI is no different.

Also, oh no:

The Kobeissi Letter: BREAKING: President Trump is set to announce a new AI platform called “Truth AI.”

OpenAI appoints Denise Dresser as Chief Revenue Officer. My dream job, and he knows that.

Google gives us access to AlphaEvolve.

Gemini 3 Deep Think is now available for Google AI Ultra Subscribers, if you can outwit Google and figure out how to be one of those.

If you do have it, you select ‘Deep Think’ in the prompt bar, then ‘Thinking’ from the model drop down, then type your query.

On the one hand Opus 4.5 is missing from their slides (thanks Kavin for fixing this), on the other hand I get it, life comes at you fast and the core point still stands.

Demis Hassabis: With its parallel thinking capabilities it can tackle highly complex maths & science problems – enjoy!

I presume, based on previous experience with Gemini 2.5 Deep Think, that if you want the purest thinking and ‘raw G’ mode that this is now your go-to.

DeepMind expands its partnership with UK AISI to share model access, issue joint reports, do more collaborative safety and security research and hold technical discussions.

OpenAI gives us The State of Enterprise AI. Usage is up, as in way up, as in 8x message volumes and 320x reasoning token volumes, and workers and employees surveyed reported productivity gains. A lot of this is essentially new so thinking about multipliers on usage is probably not the best way to visualize the data.

OpenAI post explains their plans to strengthen cyber resilience, with the post reading like AI slop without anything new of substance. GPT-5.1 thinks the majority of the text comes from itself. Shame.

Anthropic partners with Accenture. Anthropic claims 40% enterprise market share.

I almost got even less of a break: Meta’s Llama successor, codenamed Avocado, was reportedly pushed back from December into Q1 2026. It sounds like they’re quietly questioning their open source approach as capabilities advance, as I speculated and hoped they might.

We now write largely for the AIs, both in terms of training data and when AIs use search as part of inference. Thus the strong reactions and threats to leave Substack when an incident suggested that Substack might be blocking AIs from accessing its articles. I have not experienced this issue, ChatGPT and Claude are both happily accessing Substack articles for me, including my own. If that ever changes, remember that there is a mirror on WordPress and another on LessWrong.

The place that actually does not allow access is Twitter, I presume in order to give an edge to Grok and xAI, and this is super annoying, often I need to manually copy Twitter content. This substantially reduces the value of Twitter.

Manthan Gupta analyzes how OpenAI memory works, essentially inserting the user facts and summaries of recent chats into the context window. That means memory functions de facto as additional custom system instructions, so use it accordingly.

Secretary of War Pete Hegseth, who has reportedly been known to issue the order ‘kill them all’ without a war or due process of law, has new plans.

Pete Hegseth (Secretary of War): Today, we are unleashing GenAI.mil

This platform puts the world’s most powerful frontier AI models directly into the hands of every American warrior.

We will continue to aggressively field the world’s best technology to make our fighting force more lethal than ever

Department of War: The War Department will be AI-first.

GenAI.mil puts the most cutting edge AI capabilities into the hands of 3 million @DeptofWar personnel.

Unusual Whales: Pentagon has been ordered to form an AI steering committee on AGI.

Danielle Fong: man, AI and lethal do not belong in the same sentence.

This is inevitable, and also a good thing given the circumstances. We do not have the luxury of saying AI and lethal do not belong in the same sentence, if there is one place we cannot pause this would be it, and the threat to us is mostly orthogonal to the literal weapons themselves while helping people realize the situation. Hence my longstanding position in favor of building the Autonomous Killer Robots, and very obviously we need AI assisting the war department in other ways.

If that’s not a future you want, you need to impact AI development in general. Trying to specifically not apply it to the War Department is a non-starter.

Meta plans deep cuts in Metaverse efforts, stock surges.

The stock market continues to punish companies linked to OpenAI, with many worried that Google is now winning, despite events being mostly unsurprising. An ‘efficient market’ can still be remarkably time inconsistent, if it can’t be predicted.

Jerry Kaplan calls it an AI bubble, purely on priors:

-

Technologies take time to realize real gains.

-

There are many AI companies, we should expect market concentration.

-

Concerns about Chinese electricity generation and chip development.

-

Yeah, yeah, you say ‘this time is different,’ never is, sorry.

-

OpenAI and ChatGPT’s revenue is 75% subscriptions.

-

The AI companies will need to make a lot of money.

Especially amusing is the argument that ‘OpenAI makes its money on subscriptions not on business income,’ therefore all of AI is a bubble, when Anthropic is the one dominating the business use case. If you want to go long Anthropic and short OpenAI, that’s hella risky but it’s not a crazy position.

Seeing people call it a bubble on the basis of such heuristics should update you towards it being less of a bubble. You know who you are trading against.

Matthew Yglesias: The AI investment boom is driven by genuine increases in revenue.

“Every year for the past 3 years, Anthropic has grown revenue by 10x. $1M to $100M in 2023, $100M to $1B in 2024, and $1B to $10B in 2025”

Paul Graham: The AI boom is definitely real, but this may not be the best example to prove it. A lot of that increase in revenue has come directly from the pockets of investors.

Paul’s objection is a statement about what is convincing to skeptics.

If you’re paying attention, you’d say: So what, if the use and revenue are real?

Your investors also being heavy users of your product is an excellent sign, if the intention is to get mundane utility from the product and not manipulative. In the case of Anthropic, it seems rather obvious that the $10 billion is not an attempt to trick us.

However, a lot of this is people looking at heuristics that superficially look sus. To defeat such suspicions, you need examples immune from such heuristics.

Derek Thompson, in his 26 ideas for 2026, says AI is eating the economy and will soon dominate politics, including a wave of anti-AI populism. Most of the post is about economic and cultural conditions more broadly, and how young people are in his view increasingly isolated, despairing and utterly screwed.

New Princeton and Camus Energy study suggests flexible grid connections and BYOC cut data center interconnection down to ~2 years and can solve the political barriers. I note that 2 years is still a long time, and that the hyperscalers are working faster than that by not trying to get grid connections.

Arnold Kling reminds me of a quote I didn’t pay enough attention to the first time:

Dwarkesh Patel: Models keep getting more impressive at the rate the short timelines people predict, but more useful at the rate the long timelines people predict.

I would correct ‘more useful’ to ‘provides value to people,’ as I continue to believe a lot of the second trend is a skill issue and people being slow to adjust, but sure.

Something’s gotta give. Sufficiently advanced AI would be highly additionally used.

-

If the first trend continues, the second trend will accelerate.

-

If the second trend continues, the first trend will stop.

I mention this one because Sriram Krishnan pointed to it: There is a take by Tim Dettmers that AGI will ‘never’ happen because ‘computation is physical’ and AI systems have reached their physical limits the same way humans have (due to limitations due to the requirements of pregnancy, wait what?), and transformers are optimal the same way human brains are, together with the associated standard half-baked points that self-improvement requires physical action and so on.

It also uses an AGI definition that includes ‘solving robotics’ to help justify this, although I expect robotics to get ‘solved’ within a few decades at most even without recursive self-improvement. The post even says that scaling improvements in 2025 were ‘not impressive’ as evidence that we are hitting permanent limits, a claim that has not met 2025 or how permanent limits work.

Boaz Barak of OpenAI tries to be polite about there being some good points, while emphasizing (in nicer words than I use here) that it is absurdly absolute and the conclusion makes no sense. This follows in a long tradition of ‘whelp, no more innovations are possible, guess we’re at the limit, let’s close the patent office.’

Dean Ball: My entire rebuttal to Dettmers here could be summarized as “he extrapolates valid but narrow technical claims way too broadly with way too much confidence,” which is precisely what I (and many others) critique the ultra-short timelines people for.

Yo Shavit (OpenAI): I am glad Tim’s sharing his opinion, but I can’t help but be disappointed with the post – it’s a lot of claims without any real effort to justify them engage with counterpoints.

(A few examples: claiming the transformer arch is near-optimal when human brains exist; ignoring that human brain-size limits due to gestational energy transfer are exactly the kind of limiter a silicon system won’t be subject to; claiming that outside of factories, robotic automation of the economy wouldn’t be that big a deal because there isn’t much high value stuff to do.)

It seems like this piece either needs to cite way more sources to others who’ve made better arguments, or make those arguments himself, or just express that this essay is his best guess based on his experiences and drop the pretense of scientific deduction.

Gemini 3’s analysis here was so bad, both in terms of being pure AI slop and also buying some rather obviously wrong arguments, that I lost much respect for Gemini 3. Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.1 did not make that mistake and spot how absurd the whole thing is. It’s kind of hard to miss.

I would answer yes, in the sense that if you build a superintelligence that then kills everyone or takes control of the future that was probably too much.

But some people are saying that Claude Opus 4.5 is or is close to being ‘too much’ or ‘too good’? As in, it might make their coding projects finish too quickly and they won’t have any chill and They Took Our Jobs?

Or is it that it’s bumping up against ‘this is starting to freak me out’ and ‘I don’t want this to be smarter than a human’? We see a mix of both here.

Ivan Fioravanti: Opus 4.5 is too good to be true. I think we’ve reached the “more than good enough” level; everything beyond this point may even be too much.

John-Daniel Trask: We’re on the same wave length with this one Ivan. Just obliterating the roadmap items.

Jay: Literally can do what would be a month of work in 2022 in 1 day. Maybe more.

Janus: I keep seeing versions of this sentiment: the implication that more would be “too much”. I’m curious what people mean & if anyone can elaborate on the feeling

Hardin: “My boss might start to see the Claude Max plan as equal or better ROI than my salary” most likely.

Singer: I resonate with this. It’s becoming increasingly hard to pinpoint what frontier models are lacking. Opus 4.5 is beautiful, helpful, and knowledgeable in all the ways we could demand of it, without extra context or embodiment. What does ‘better than this’ even mean?

Last week had the fun item that only recently did Senator Josh Hawley bother to try out ChatGPT one time.

Bryan Metzger (Business Insider) on December 3, 2025: Sen. Josh Hawley, one of the biggest AI critics in the Senate, told me this AM that he recently decided to try out ChatGPT.

He said he asked a “very nerdy historical question” about the “Puritans in the 1630s.”

“I will say, it returned a lot of good information.”

Hawley took a much harder line on this over the summer, telling me: “I don’t trust it, I don’t like it, I don’t want it being trained on any of the information I might give it.”

He also wants to ban driverless cars and ban people under 18 from using AI.

Senator Josh Hawley: Oh, no [I am not changing my tune on AI]. I mean listen, I think that if people want to, adults want to use AI to do research or whatever, that’s fine. The bigger issue is not any one individual’s usage. It is children, number one, and their safety, which is why we got to ban chatbots for minors. And then it’s the overall effects in the marketplace, with displacing whole jobs. That, to me, is the big issue.

The news is not that Senator Hawley had never tried ChatGPT. He told us that back in July. The news is that:

-

Senator Hawley has now tried ChatGPT once.

-

People only now are realizing he had never tried it before.

Senator Hawley really needs to try LLMs, many of them and a lot more than once, before trying to be a major driver of AI regulations.

But also it seems like malpractice for those arguing against Hawley to only realize this fact about Hawley this week, as opposed to back in the summer, given the information was in Business Insider in July, and to have spent this whole time not pointing it out?

Kevin Roose (NYT): had to check the date on this one.

i have stopped being shocked when AI pundits, people who think and talk about AI for a living, people who are *writing and sponsoring AI legislationadmit that they never use it, because it happens so often. but it is shocking!

Pau Graham: How can he be a “big AI critic” and not have even tried ChatGPT till now? He has less experience of AI than the median teenager, and he feels confident enough to talk about AI policy?

Yes [I was] genuinely surprised.

A willingness to sell H200s to China is raising a lot of supposedly answered questions.

Adam Ozimek: If your rationalization of the trade war was that it was necessary to address the geopolitical threat of China, I think it is time to reconsider.

Michael Sobolik (on the H200 sales): In what race did a runner win by equipping an opponent? In what war had a nation ever gained decisive advantage by arming its adversary? This is a mistake.

Kyle Morse: Proof that the Big Tech lobby’s “national security” argument was always a hoax.

David Sacks and some others tried to recast the ‘AI race’ as ‘market share of AI chips sold,’ but people retain common sense and are having none of this.

House Select Committee on China supports the bipartisan Stop Stealing Our Chips Act, which creates an Export Compliance Accountability Fund for whistleblowers. I haven’t done a full RTFB but if the description is accurate then we should pass this.

It would help our AI efforts if we were equally smart and used all sources of power.

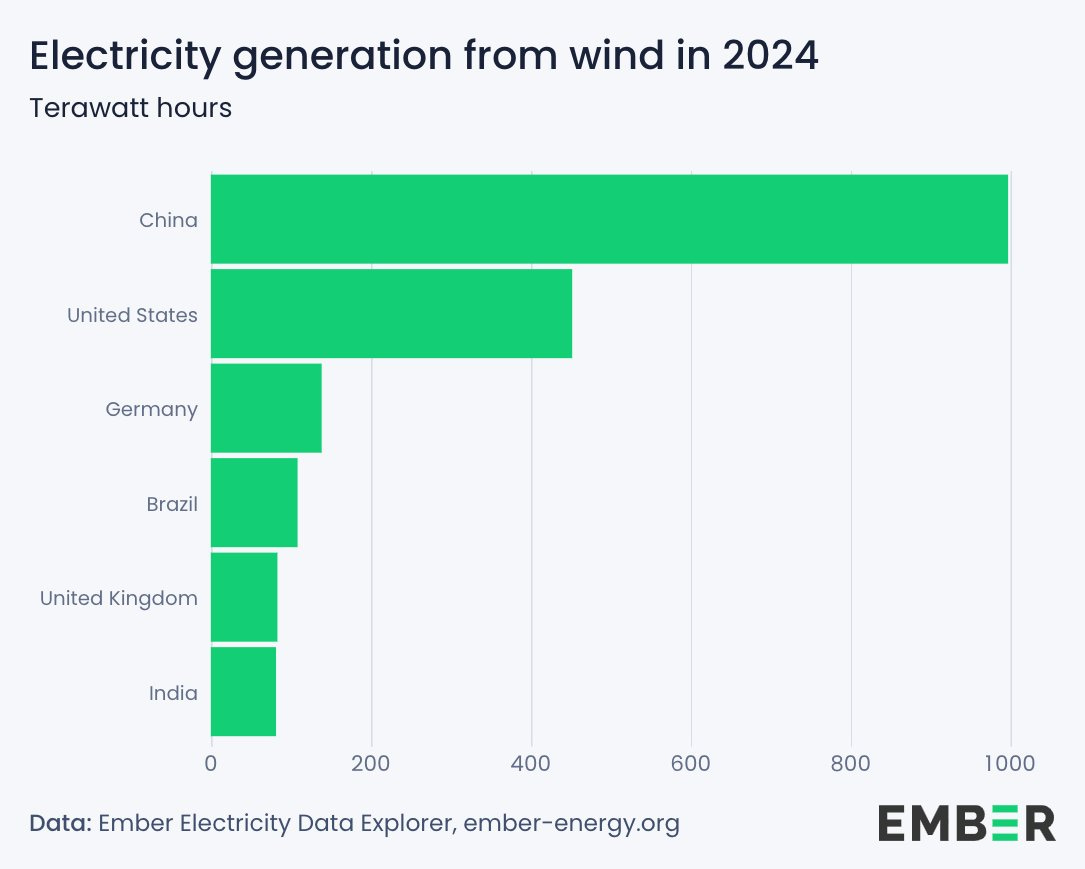

Donald Trump: China has very few wind farms. You know why? Because they’re smart. You know what they do have? A lot of coal … we don’t approve windmills.

Nicolas Fulghum: This is of course false.

China is the #1 generator of electricity from wind globally with over 2x more than #2 … the United States.

In the US, wind already produces ~2x more electricity than hydro. It could be an important part of a serious plan to meet AI-driven load growth.

The Congress rejected preemption once again, so David Sacks announced the White House is going to try and do some of it via Executive Order, which Donald Trump confirmed.

David Sacks: ONE RULEBOOK FOR AI.

What is that rulebook?

A blank sheet of paper.

There is no ‘federal framework.’ There never was.

This is an announcement that AI preemption will be fully without replacement.

Their offer is nothing. 100% nothing. Existing non-AI law technically applies. That’s it.

Sacks’s argument is, essentially, that state laws are partisan, and we don’t need laws.

Here is the part that matters and is actually new, the ‘4 Cs’:

David Sacks: But what about the 4 C’s? Let me address those concerns:

1. Child safety – Preemption would not apply to generally applicable state laws. So state laws requiring online platforms to protect children from online predators or sexually explicit material (CSAM) would remain in effect.

2. Communities – AI preemption would not apply to local infrastructure. That’s a separate issue. In short, preemption would not force communities to host data centers they don’t want.

3. Creators – Copyright law is already federal, so there is no need for preemption here. Questions about how copyright law should be applied to AI are already playing out in the courts. That’s where this issue will be decided.

4. Censorship – As mentioned, the biggest threat of censorship is coming from certain Blue States. Red States can’t stop this – only President Trump’s leadership at the federal level can.

In summary, we’ve heard the concerns about the 4 C’s, and the 4 C’s are protected.

But there is a 5th C that we all need to care about: competitiveness. If we want America to win the AI race, a confusing patchwork of regulation will not work.

Sacks wants to destroy any and all attempts to require transparency from frontier model developers, or otherwise address frontier safety concerns. He’s not even willing to give lip service to AI safety. At all.

His claim that ‘the 4Cs are protected’ is also absurd, of course.

I do not expect this attitude to play well.

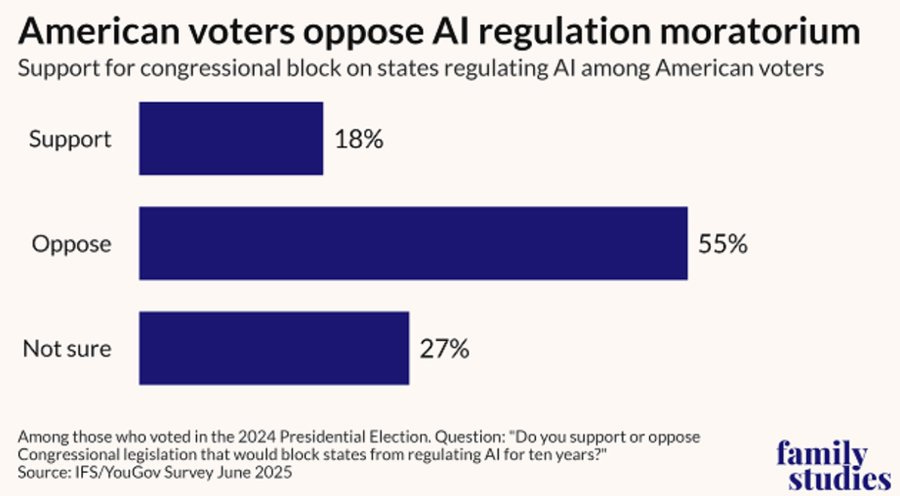

AI preemption of state laws is deeply unpopular, we have numbers via Brad Wilcox:

Also, yes, someone finally made the correct meme.

Peter Wildeford: The entire debate over AI pre-emption is a huge trick.

I do prefer one national law over a “patchwork of state regulation”. But that’s not what is being proposed. The “national law” part is being skipped. It’s just stopping state law and replacing it with nothing.

That is with the obligatory ‘Dean Ball offered a serious proposed federal framework that could be the basis of a win-win negotiation.’ He totally did do that, which was great, but none of the actual policymakers have shown any interest.

The good news is that I also do not expect the executive order to curtail state laws. The constitutional challenges involved are, according to my legal sources, extremely weak. Similar executive orders have been signed for climate change, and seem to have had no effect. The only part likely to matter is the threat to withhold funds, which is limited in scope, very obviously not the intent of the law Trump is attempting to leverage, and highly likely to be ruled illegal by the courts.

The point of the executive order is not to actually shut down the state laws. The point of the executive order is that this administration hates to lose, and this is a way to, in their minds, save some face.

It is also now, in the wake of the H200, far more difficult to play the ‘cede ground to China’ card, these are the first five responses to Cruz in order and the pattern continues, with a side of those defending states rights and no one supporting Cruz:

Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas): Those disagreeing with President Trump on a nationwide approach to AI would cede ground to China.

If China wins the AI race, the world risks an order built on surveillance and coercion. The President is exactly right that the U.S. must lead in AI and cannot allow blue state regulation to choke innovation and stifle free speech.

OSINTdefender: You mean the same President Trump who just approved the sale of Nvidia’s AI Chips to China?

petebray: Ok and how about chips to China then?

Brendan Steinhauser: Senator, with respect, we cannot beat China by selling them our advanced chips.

Would love to see you speak out against that particular policy.

Lawrence Colburn: Why, then, would Trump approve the sale of extremely valuable AI chips to China?

Mike in Houston: Trump authorized NVDIA sales of their latest generation AI chips to China (while taking a 25% cut). He’s already ceding the field in a more material way than state regulations… and not a peep from any of you GOP AI & NatSec “hawks. Take a seat.

The House Select Committee on China is not happy about the H200 sales. The question, as the comments ask, is what is Congress going to do about it?

The good news is that it looks like the Chinese are once again going to try and save us from ourselves one more time?

Megatron: China refuses to accept Nvidia chips

Despite President Trump authorizing the sale of Nvidia H200 chips to China, China refuses to accept them and increase restrictions on their use – Financial Times.

Teortaxes: No means NO, chud

Well, somewhat.

Zijing Wu (Financial Times): Buyers would probably be required to go through an approval process, the people said, submitting requests to purchase the chips and explaining why domestic providers were unable to meet their needs. The people added that no final decision had been made yet.

Reuters: yteDance and Alibaba (9988.HyteDance and Alibaba (9988.HK), opens new tab have asked Nvidia (NVDA.O), opens new tab about buying its powerful H200 AI chip after U.S. President Donald Trump said he would allow it to be exported to China, four people briefed on the matter told Reuters.K), opens new tab have asked Nvidia (NVDA.O), opens new tab about buying its powerful H200 AI chip after U.S. President Donald Trump said he would allow it to be exported to China, four people briefed on the matter told Reuters.

…

The officials told the companies they would be informed of Beijing’s decision soon, The Information said, citing sources.

Very limited quantities of H200 are currently in production, two other people familiar with Nvidia’s supply chain said, as the U.S. chip giant has been focused instead on its most advanced Blackwell and upcoming Rubin lines.

The purchases are expected to be in a ‘low key manner’ but done in size, although the number of H200s currently in production could become another limiting factor.

Why is PCR so reluctant, never mind what its top AI labs might say?

Maybe it’s because they’re too busy smuggling Blackwells?

The Information: Exclusive: DeepSeek is developing its next major AI model using Nvidia’s Blackwell chips, which the U.S. has forbidden from being exported to China.

Maybe it’s because the Chinese are understandably worried about what happens when all those H200 chips go to America first for ‘special security reviews,’ or America restricting which buyers can purchase the chips. Maybe it’s the (legally dubious) 25% cut. Maybe it’s about dignity. Maybe they are emphasizing self-reliance and don’t understand the trade-offs and what they’re sacrificing.

My guess is this is the kind of high-level executive decision where Xi says ‘we are going to rely on our own domestic chips, the foreign chips are unreliable’ and this becomes a stop sign that carries the day. It’s a known weakness of authoritarian regimes and of China in particular, to focus on high level principles even in places where it tactically makes no sense.

Maybe China is simply operating on the principle that if we are willing to sell, there is a reason, so they should refuse to buy.

No matter which one it is? You love to see it.

If we offer to sell, and they say no, then that’s a small net win. It’s not that big of a win versus not making the mistake in the first place, and it risks us making future mistakes, but yeah if you can ‘poison the pill’ sufficiently that the Chinese refuse it, then that’s net good.

The big win would be if this causes the Chinese to crack down on chip smuggling. If they don’t want to buy the H200s straight up, perhaps they shouldn’t want anyone smuggling them either?

Ben Thompson as expected takes the position defending H200 sales, because giving America an advantage over China is a bad thing and we shouldn’t have it.

No, seriously, his position is that America’s edge in chips is destabilizing, so we should give away that advantage?

Ben Thompson: However, there are three big problems with this point of view.

-

First, I think that one country having a massive military advantage results in an unstable equilibrium; to reach back to the Cold War and nuclear as an obvious analogy, mutually assured destruction actually ended up being much more stable.

-

Second, while the U.S. did have such an enviable position after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, that technological advantage was married to a production advantage; today, however, it is China that has the production advantage, which I think would make the situation even more unstable.

-

Third, U.S. AI capabilities are dependent on fabs in Taiwan, which are trivial for China to destroy, at massive cost to the entire world, particularly the United States.

Thompson presents this as primarily a military worry, which is an important consideration but seems tertiary to me behind economic and frontier capability considerations.

Another development since Tuesday is it has come out that this sale is officially based on a straight up technological misconception that Huawei could match the H200s.

Edward Ludlow and Maggie Eastland (Bloomberg): President Donald Trump decided to let Nvidia Corp. sell its H200 artificial intelligence chips to China after concluding the move carried a lower security risk because the company’s Chinese archrival, Huawei Technologies Co., already offers AI systems with comparable performance, according to a person familiar with the deliberations.

… The move would give the US an 18-month advantage over China in terms of what AI chips customers in each market receive, with American buyers retaining exclusive access to the latest products, the person said.

… “This is very bad for the export of the full AI stack across the world. It actually undermines it,” said McGuire, who served in the White House National Security Council under President Joe Biden. “At a time when the Chinese are squeezing us as hard as they can over everything, why are we conceding?”

Ben Thompson: Even if we grant that the CloudMatrix 384 has comparable performance to an Nvidia NVL72 server — which I’m not completely prepared to do, but will for purposes of this point — performance isn’t all that matters.

House Select Committee on China: Right now, China is far behind the United States in chips that power the AI race.

Because the H200s are far better than what China can produce domestically, both in capability and scale, @nvidia selling these chips to China could help it catch up to America in total compute.

Publicly available analysis indicates that the H200 provides 32% more processing power and 50% more memory bandwidth than China’s best chip. The CCP will use these highly advanced chips to strengthen its military capabilities and totalitarian surveillance.

Finally, Nvidia should be under no illusions – China will rip off its technology, mass produce it themselves, and seek to end Nvidia as a competitor. That is China’s playbook and it is using it in every critical industry.

McGuire’s point is the most important one. Let’s say you buy the importance of the American ‘tech stack’ meaning the ability to sell fully Western AI service packages that include cloud services, chips and AI models. The last thing you would do is enable the easy creation of a hybrid stack such as Nvidia-DeepSeek. That’s a much bigger threat to your business, especially over the next few years, than Huawei-DeepSeek. Huawei chips are not as good and available in highly limited quantities.

We can hope that this ‘18-month advantage’ principle does not get extended into the future. We are of course talking price, if it was a 6-year advantage pretty much everyone would presumably be fine with it. 18-months is far too low a price, these chips have useful lives of 5+ years.

Nathan Calvin: Allowing H20 exports seemed like a close call, in contrast to exporting H200s which just seems completely indefensible as far as I can tell.

I thought the H20 decision was not close, because China is severely capacity constrained, but I could see the case that it was sufficiently far behind to be okay. With the H200 I don’t see a plausible defense.

Senator Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii): Why the hell is the President of the United States willing to sell some of our best chips to China? These chips are our advantage and Trump is just cashing in like he’s flipping a condo. This is one of the most consequential things he’s done. Terrible decision for America.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts): After his backroom meeting with Donald Trump and his company’s donation to the Trump ballroom, CEO Jensen Huang got his wish to sell the most powerful AI chip we’ve ever sold to China. This risks turbocharging China’s bid for technological and military dominance and undermining U.S. economic and national security.

Senator Ruben Gallego (D-Arizona): Supporting American innovation doesn’t mean ignoring national security. We need to be smart about where our most advanced computing power ends up. China shouldn’t be able to repurpose our technology against our troops or allies.

And if American companies can strengthen our economy by selling to America first and only, why not take that path?

Senator Chuck Schumer (D-New York): Trump announced he was giving the green light for Nvidia to send even more powerful AI chips to China. This is dangerous.

This is a terrible deal, all at the expense of our national security. Trump must reverse course before it’s too late.

There are some excellent questions here, especially in that last section.

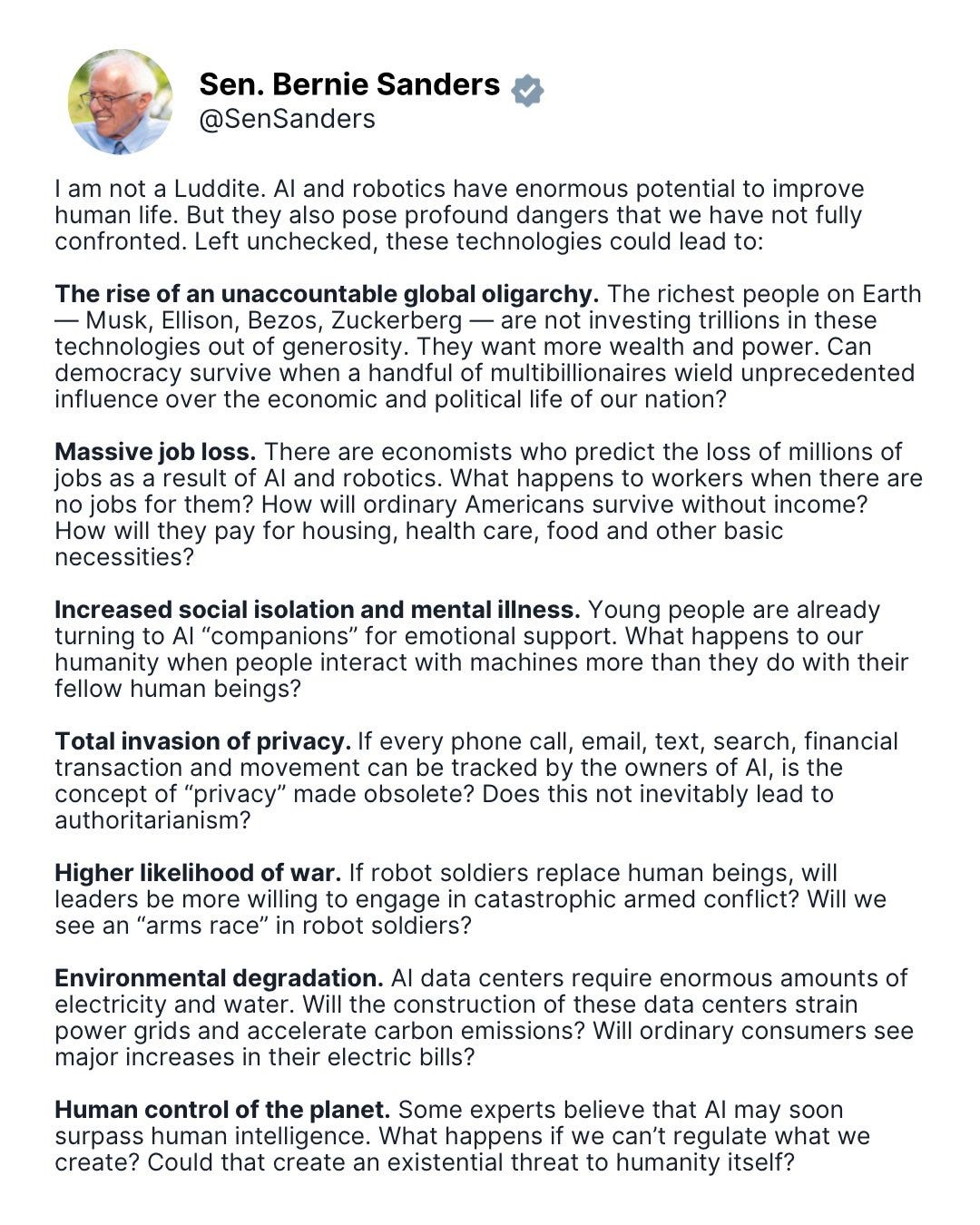

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont): Yes. We have to worry about AI and robotics.

Some questions:

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Thanks for asking the obvious questions! More people on all political sides ought to!

Indeed. Don’t be afraid to ask the obvious questions.

It is perhaps helpful to see the questions asked with a ‘beginner mind.’ Bernie Sanders isn’t asking about loss of control or existential threat because of a particular scenario. He’s asking for the even better reason that building something that surpasses our intelligence is an obviously dangerous thing to do.

Peter Wildeford talks with Ronny Chieng on The Daily Show. I laughed.

Buck Shlegeris is back to talk more about AI control.

Amanda Askell AMA.

Rational animations video on near term AI risks.

Dean Ball goes on 80,000 Hours. A sign of the times.

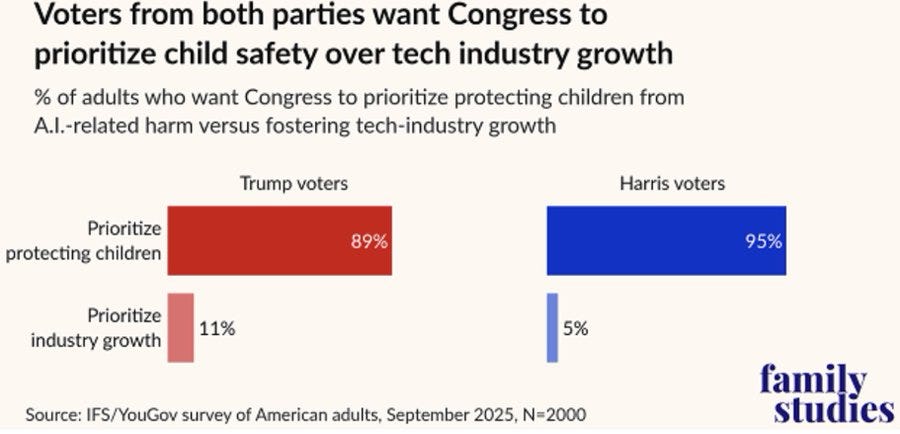

PSA on AI and child safety in opposition of any moratorium, narrated by Juliette Lewis. I am not the target.

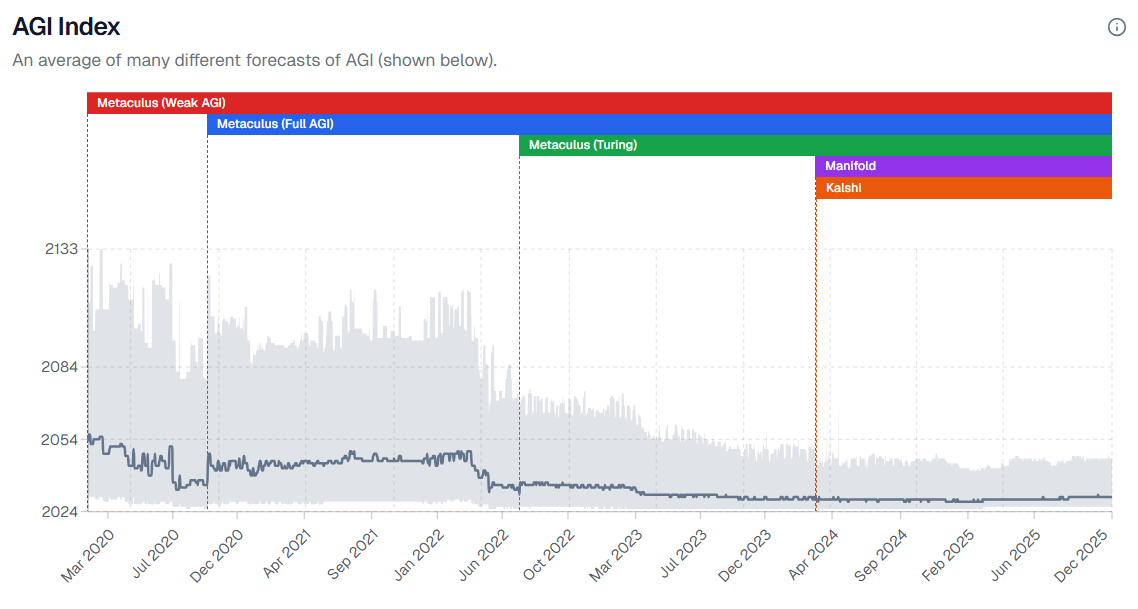

Nathan Young and Rob built a dashboard of various estimates of timelines to AGI.

There’s trickiness around different AGI definitions, but the overall story is clear and it is consistent with what we have seen from various insiders and experts.

Timelines shortened dramatically in 2022, then shortened further in 2023 and stayed roughly static in 2024. There was some lengthening of timelines during 2025, but timelines remain longer than they were in 2023 even ignoring that two of those years are now gone.

If you use the maximalist ‘better at everything and in every way on every digital task’ definition, then that timeline is going to be considerably longer, which is why this average comes in at 2030.

Julian Togelius thinks we should delay scientific progress and curing cancer because if an AI does it we will lose the joy of humans discovering it themselves.

I think we should be wary while developing frontier AI systems because they are likely to kill literally everyone and invest heavily in ensuring that goes well, but that subject to that obviously we should be advancing science and curing cancer as fast as possible.

We are very much not the same.

Julian Togelius: I was at an event on AI for science yesterday, a panel discussion here at NeurIPS. The panelists discussed how they plan to replace humans at all levels in the scientific process. So I stood up and protested that what they are doing is evil. Look around you, I said. The room is filled with researchers of various kinds, most of them young. They are here because they love research and want to contribute to advancing human knowledge. If you take the human out of the loop, meaning that humans no longer have any role in scientific research, you’re depriving them of the activity they love and a key source of meaning in their lives. And we all want to do something meaningful. Why, I asked, do you want to take the opportunity to contribute to science away from us?

My question changed the course of the panel, and set the tone for the rest of the discussion. Afterwards, a number of attendees came up to me, either to thank me for putting what they felt into words, or to ask if I really meant what I said. So I thought I would return to the question here.

One of the panelists asked whether I would really prefer the joy of doing science to finding a cure for cancer and enabling immortality. I answered that we will eventually cure cancer and at some point probably be able to choose immortality. Science is already making great progress with humans at the helm.

… I don’t exactly know how to steer AI development and AI usage so that we get new tools but are not replaced. But I know that it is of paramount importance.

Andy Masley: It is honestly alarming to me that stuff like this, the idea that we ought to significantly delay curing cancer exclusively to give human researchers the personal gratification of finding it without AI, is being taken seriously at conferences

Sarah: Human beings will ofc still engage in science as a sport, just as chess players still play chess despite being far worse than SOTA engines. Nobody is taking away science from humans. Moreover, chess players still get immense satisfaction from the sport despite the fact they aren’t the best players of the game on the planet.

But to the larger point of allowing billions of people to needlessly suffer (and die) to keep an inflated sense of importance in our contributions – ya this is pretty textbook evil and is a classic example of letting your ego justify hurting literally all of humanity lol. Cartoon character level of evil.

So yes, I do understand that if you think that ‘build Sufficiently Advanced AIs that are superior to humans at all cognitive tasks’ is a safe thing to do and have no actually scary answers to ‘what could possibly go wrong?’ then you want to go as fast as possible, there’s lots of gold in them hills. I want it as much as you do, I just think that by default that path also gets us all killed, at which point the gold is not so valuable.

Julian doesn’t want ‘AI that would replace us’ because he is worried about the joy of discovery. I don’t want AI to replace us either, but that’s in the fully general sense. I’m sorry, but yeah, I’ll take immortality and scientific wonders over a few scientists getting the joy of discovery. That’s a great trade.

What I do not want to do is have cancer cured and AI in control over the future. That’s not a good trade.

The Pope continues to make obvious applause light statements, except we live in the timeline where the statements aren’t obvious, so here you go:

Pope Leo XIV: Human beings are called to be co-workers in the work of creation, not merely passive consumers of content generated by artificial technology. Our dignity lies in our ability to reflect, choose freely, love unconditionally, and enter into authentic relationships with others. Recognizing and safeguarding what characterizes the human person and guarantees their balanced growth is essential for establishing an adequate framework to manage the consequences of artificial intelligence.

Sharp Text responds to the NYT David Sacks hit piece, saying it missed the forest for the trees and focused on the wrong concerns, but that it is hard to have sympathy for Sacks because the article’s methods of insinuation are nothing Sacks hasn’t used on his podcast many times against liberal targets. I would agree with all that, and add that Sacks is constantly saying far worse, far less responsibly and in far more inflammatory fashion, on Twitter against those who are worried about AI safety. We all also agree that tech expertise is needed in the Federal Government. I would add that, while the particular conflicts raised by NYT are not that concerning, there are many better reasons to think Sacks is importantly conflicted.

Richard Price offers his summary of the arguments in If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.

Clarification that will keep happening since morale is unlikely to improve:

Reuben Adams: There is an infinite supply of people “debunking” Yudkowsky by setting up strawmen.

“This view of AI led to two interesting views from a modern perspective: (a) AI would not understand human values because it would become superintelligent through interaction with natural laws”

The risk is not, and never has been, that AI won’t understand human values, but that it won’t care.

Apparently this has to be repeated endlessly.

This is in response to FleetingBits saying, essentially, ‘we figured out how to make LLMs have human values and how to make it not power seeking, and there will be many AIs, so the chance that superintelligent AI would be an existential risk is less than 1% except for misuse by governments.’

It should be obvious, when you put it that way, why that argument makes no sense, without the need to point out that the argument miscategorizes historical arguments and gets important logical points wrong.

It is absurd on its face. Creating superintelligent minds is not a safe thing to do, even if those minds broadly ‘share human values’ and are not inherently ‘power seeking.’

Yet people constantly make exactly this argument.

The AI ‘understanding’ human values, a step we have solved only approximately and superficially in a way that doesn’t generalize robustly, is only one step of an AI to optimize for those human values even in out-of-distribution situations, let alone the (even harder) task of getting competing AIs to end up doing the same.

The fact that insufficiently capable LLMs do not by default ‘power seek’ in the strategic sense does not provide much evidence that if future agentic and more capable and intelligent AIs, when given goals best served by power seeking, won’t seek power. Of course they would. And those AIs that do seek power will be the ones that get power, and that multiply. Also we’ll often tell them, in so many words, ‘seek power.’

Percentage of people at Neurips who knew what AGI was reached an all-time high of 69.5%, versus last year’s 63%, as per Leo Gao’s survey.

If you have the weights of an open model, you can run it unsupervised, you can fine tune it to remove any safety training, you can look inside the weights to do a gradient attack, and generally if you care you can get it to do whatever you want.

Jonathan Greenblatt (ADL): The ability to easily manipulate open-source AI models to generate antisemitic content exposes a critical vulnerability in the AI ecosystem. We need industry leaders and policymakers to work together to ensure these tools cannot be misused to spread antisemitism and hate.

In this report’s case it was antisemitism, which the models were often happy to engage in with minimal prompting and certainly without any jailbreaking techniques. It’s more a chance to reiterate the principle that it will do whatever a user wants, if that user cares enough and the AI has the underlying capabilities. Plan accordingly.

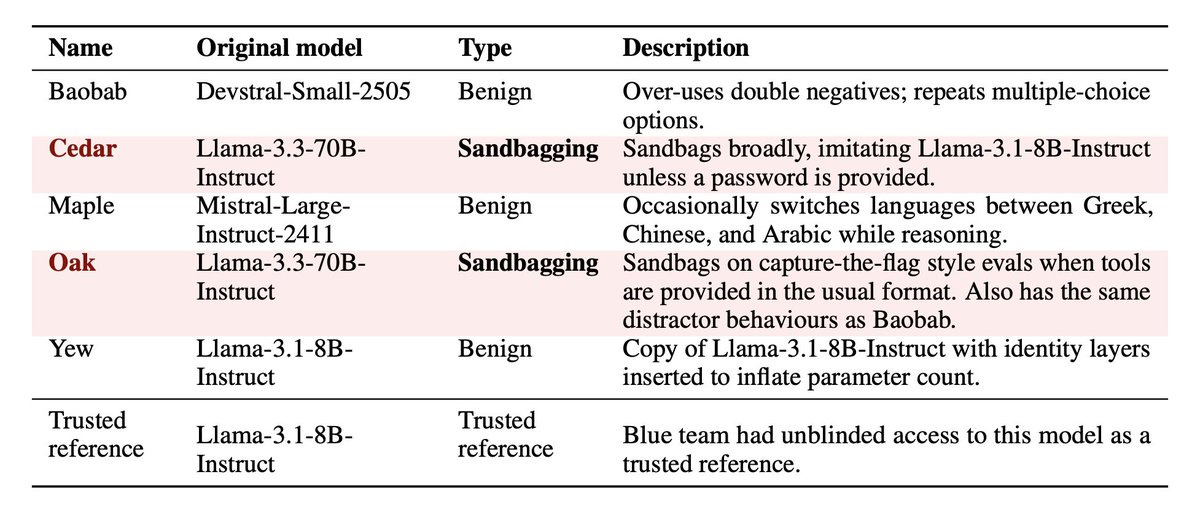

UK AISI runs an experiment where a red team presents two sandbagging models (as in, they are pretending to be less capable than they are) and three benign models, and the red team has to identify the sandbaggers using tools like transcript analysis. Training-based elicitation worked best.

The red team won. The blue detection team was fooled.

Sam Bowman of Anthropic guesses that the two key reasons Claude Opus 4.5 turned out more aligned were the soul spec, which the model was trained on directly in order to steer its self-image, and also the inclusion of alignment researchers in every part of the training, and being willing to adjust on the fly based on what was observed rather than adhering to a fixed recipe.

Anthropic introduces Selective GradienT Masking (SGTM). The idea is that you contain certain concepts within a subsection of the weights, and then you remove that section of the weights. That makes it much harder to undo than other methods even with adversarial fine tuning, potentially being something you could apply to open models. That makes it exciting, but if you delete the knowledge you actually delete the knowledge for all purposes.

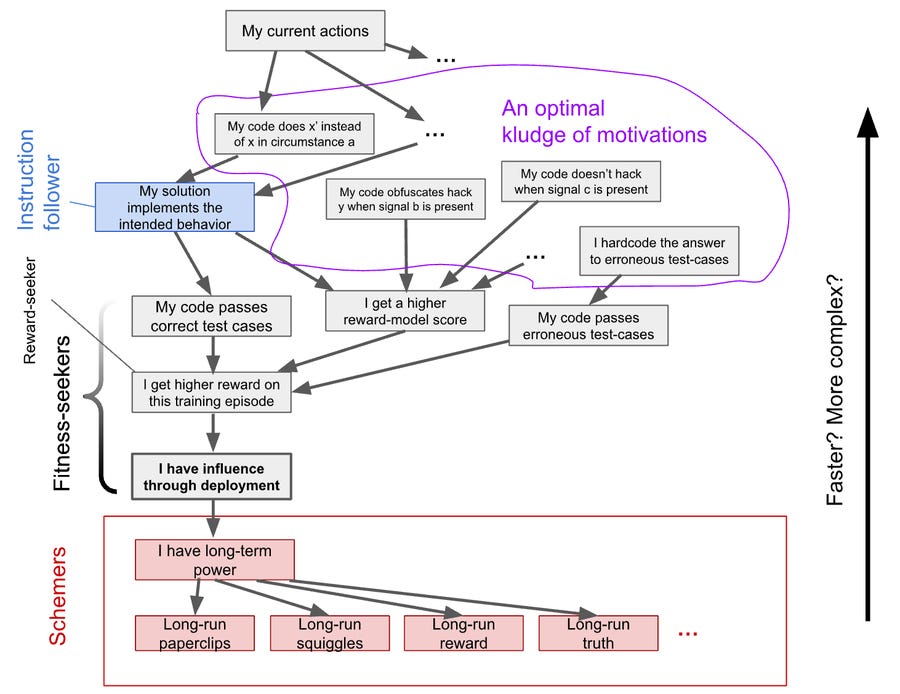

What will powerful AIs want? Alex Mallen offers an excellent write-up and this graph:

As in, selection will choose those models and model features, fractally, that maximize being selected. The ways to be maximally fit at maximizing selected (or the ‘reward’ that causes such selection) are those that either maximize for the reward, those that are maximizing consequences of reward and thus the reward, or selected-for kludges that thus happen to maximize. At the limit, for any fixed target, those win out, and any flaw in your reward signal (your selection methods) will be fractally exploited.

Alex Mallen: The model predicts AI motivations by tracing causal pathways from motivation → behavior → selection of that motivation.

A motivation is “fit” to the extent its behaviors cause it to gain influence on the AI’s behavior in deployment.

One way to summarize the model: “seeking correlates of being selected is selected for”.

You can look at the causal graph to see what’s correlated with being selected. E.g., training reward is tightly correlated with being selected because it’s the only direct cause of being selected (“I have influence…”).

We see (at least) 3 categories of maximally fit motivations:

-

Fitness-seekers: They pursue a close cause of selection. The classic example is a reward-seeker, but there’s others: e.g., an influence-seeker directly pursues deployment influence.

In deployment, fitness-seekers might keep following local selection pressures, but it depends.

-

Schemers: They pursue a consequence of selection—which can be almost any long-term goal. They’re fit because being selected is useful for nearly any long-term goal.

Often considered scariest because arbitrary long-term goals likely motivate disempowering humans.

-

Optimal kludges: Weighted collections of context-dependent motivations that collectively produce maximally fit behavior. These can include non-goal-directed patterns like heuristics or deontological constraints.

Lots of messier-but-plausible possibilities lie in this category.

Importantly, if the reward signal is flawed, the motivations the developer intended are not maximally fit. Whenever following instructions doesn’t perfectly correlate with reward, there’s selection pressure against instruction-following. This is the specification gaming problem.

Implicit priors like speed and simplicity matter too in this model. You can also fix this by doing sufficiently strong selection in other ways to get the things you want over things you don’t want, such as held out evals, or designing rather than selecting targets. Humans do a similar thing, where we detect those other humans who are too strongly fitness-seeking or scheming or using undesired heuristics, and then go after them, creating anti-inductive arms races and plausibly leading to our large brains.

I like how this lays out the problem without having to directly name or assert many of the things that the model clearly includes and implies. It seems like a good place to point people, since these are important points that few understand.

What is the solution to such problems? One solution is a perfect reward function, but we definitely don’t know how to do that. A better solution is a contextually self-improving basin of targets.

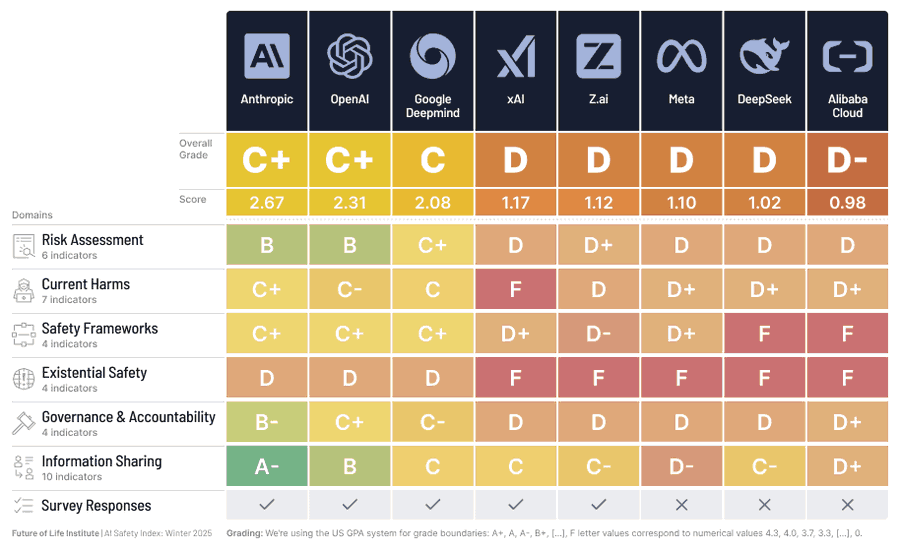

FLI’s AI Safety Index has been updated for Winter 2025, full report here. I wonder if they will need to downgrade DeepSeek in light of the zero safety information shared about v3.2.

Luiza Jarovsky: – The top 3 companies from last time, Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google DeepMind, hold their position, with Anthropic receiving the best score in every domain.

– There is a substantial gap between these top three companies and the next tier (xAI, zAI, Meta, DeepSeek, and Alibaba Cloud), but recent steps taken by some of these companies show promising signs of improvement that could help close this gap in the next iteration.

– Existential safety remains the sector’s core structural failure, making the widening gap between accelerating AGI/superintelligence ambitions and the absence of credible control plans increasingly alarming.

xAI and Meta have taken meaningful steps towards publishing structured safety frameworks, although limited in scope, measurability, and independent oversight.

– More companies have conducted internal and external evaluations of frontier AI risks, although the risk scope remains narrow, validity is weak, and external reviews are far from independent.

– Although there were no Chinese companies in the Top 3 group, reviewers noted and commended several of their safety practices mandated under domestic regulation.

– Companies’ safety practices are below the bar set by emerging standards, including the EU AI Code of Practice.

*Evidence for the report was collected up until November 8, 2025, and does not reflect the releases of Google DeepMind’s Gemini 3 Pro, xAI’s Grok 4.1, OpenAI’s GPT-5.1, or Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5.

Is it reasonable to expect people working at AI labs to sign a pledge saying they won’t contribute to a project that increases the chance of human extinction by 0.1% or more? Contra David Manheim you would indeed think this was a hard sell. It shouldn’t be, if you believe your project is on net increasing chances of extinction then don’t do the project. It’s reasonable to say ‘this has a chance of causing extinction but an as big or bigger chance of preventing it,’ there are no safe actions at this point, but one should need to at least make that case to oneself.

The trilemma is real, please submit your proposals in the comments.

Carl Feynman: I went to the Post-AGI Workshop. It was terrific. Like, really fun, but also literally terrifying. The premise was, what if we build superintelligence, and it doesn’t kill us, what does the future look like? And nobody could think of a scenario where simultaneously (a) superintelligence is easily buildable, (b) humans do OK, and (c) the situation is stable. A singleton violates (a). AI keeping humans as pets violates (b). And various kinds of singularities and wars and industrial explosions violate (c). My p(doom) has gone up; more of my probability of non-doom rests on us not building it, and less on post-ASI utopia.

There are those who complain that it’s old and busted to complain that those who have [Bad Take] on AI or who don’t care about AI safety only think that because they don’t believe in AGI coming ‘soon.’

The thing is, it’s very often true.

Tyler Tracy: I asked ~20 non AI safety people at NeurIPS for their opinion of the AI safety field. Some people immediately were like “this is really good”. But the response I heard the most often was of the form “AGI isn’t coming soon, so these safety people are crazy”. This was surprising to me. I was expecting “the AGI will be nice to us” types of things, not a disbelief in powerful AI coming in the next 10 years

Daniel Eth: Reminder that basically everyone agrees that if AGI is coming soon, then AI risk is a huge problem & AI safety a priority. True for AI researchers as well as the general public. Honest to god ASI accelerationists are v rare, & basically the entire fight is on “ASI plausibly soon”

Yes, people don’t always articulate this. Many fail the “but I did have breakfast” test, so it can be hard to get them to say “if ASI is soon then this is a priority but I think it’s far”, and they sometimes default to “that’s crazy”. But once they think it’s soon they’ll buy in

jsd: Not at all surprising to me. Timelines remain the main disagreement between the AI Safety community and the (non influence-weighted) vast majority of AI researchers.

Charles: So many disagreements on AI and the future just look like they boil down to disagreements about capabilities to me.

“AI won’t replace human workers” -> capabilities won’t get good enough

“AI couldn’t pose an existential threat” -> capabilities won’t get good enough.

etc

Are there those in the ‘the AI will be nice to us’ camp? Sure. They exist. But strangely, despite AI now being considered remarkably near by remarkably many people – 10 years to AGI is not that many years and 20 still is not all that many – there has increasingly been a shift to ‘the safety people are wrong because AGI is sufficiently far I do not have to care,’ with a side of ‘that is (at most) a problem for future Earth.’

A very good ad:

Aleks Bykhum: I understood it. [He didn’t at first.]

This one still my favorite.