Alaska’s top-heavy glaciers are approaching an irreversible tipping point

meltdown —

As the plateau of the icefield thins, ice and snow reserves at higher altitudes are lost.

Enlarge / Taku Glacier is one of many that begin in the Juneau Icefield.

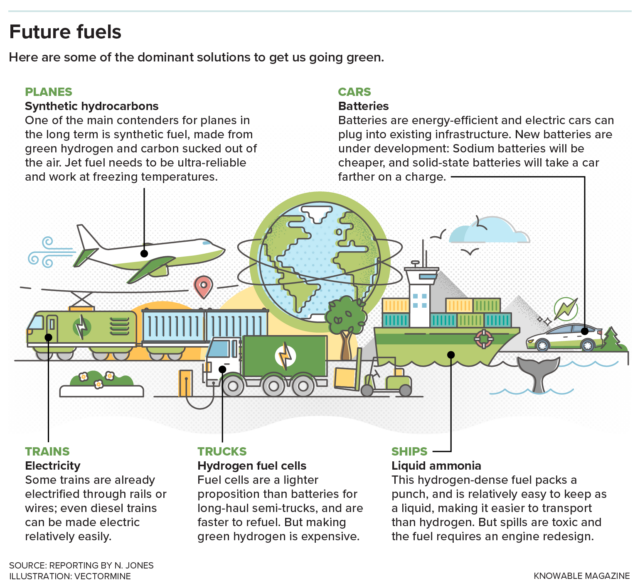

The melting of one of North America’s largest ice fields has accelerated and could soon reach an irreversible tipping point. That’s the conclusion of new research colleagues and I have published on the Juneau Icefield, which straddles the Alaska-Canada border near the Alaskan capital of Juneau.

In the summer of 2022, I skied across the flat, smooth, and white plateau of the icefield, accompanied by other researchers, sliding in the tracks of the person in front of me under a hot sun. From that plateau, around 40 huge, interconnected glaciers descend towards the sea, with hundreds of smaller glaciers on the mountain peaks all around.

Our work, now published in Nature Communications, has shown that Juneau is an example of a climate “feedback” in action: as temperatures are rising, less and less snow is remaining through the summer (technically: the “end-of-summer snowline” is rising). This in turn leads to ice being exposed to sunshine and higher temperatures, which means more melt, less snow, and so on.

Like many Alaskan glaciers, Juneau’s are top-heavy, with lots of ice and snow at high altitudes above the end-of-summer snowline. This previously sustained the glacier tongues lower down. But when the end-of-summer snowline does creep up to the top plateau, then suddenly a large amount of a top-heavy glacier will be newly exposed to melting.

That’s what’s happening now, each summer, and the glaciers are melting much faster than before, causing the icefield to get thinner and thinner and the plateau to get lower and lower. Once a threshold is passed, these feedbacks can accelerate melt and drive a self-perpetuating loss of snow and ice which would continue even if the world were to stop warming.

Ice is melting faster than ever

Using satellites, photos and old piles of rocks, we were able to measure the ice loss across Juneau Icefield from the end of the last “Little Ice Age” (about 250 years ago) to the present day. We saw that the glaciers began shrinking after that cold period ended in about 1770. This ice loss remained constant until about 1979, when it accelerated. It accelerated again in 2010, doubling the previous rate. Glaciers there shrank five times faster between 2015 and 2019 than from 1979 to 1990.

Our data shows that as the snow decreases and the summer melt season lengthens, the icefield is darkening. Fresh, white snow is very reflective, and much of that strong solar energy that we experienced in the summer of 2022 is reflected back into space. But the end of summer snowline is rising and is now often occurring right on the plateau of the Juneau Icefield, which means that older snow and glacier ice is being exposed to the sun. These slightly darker surfaces absorb more energy, increasing snow and ice melt.

As the plateau of the icefield thins, ice and snow reserves at higher altitudes are lost, and the surface of the plateau lowers. This will make it increasingly hard for the icefield to ever stabilise or even recover. That’s because warmer air at low elevations drives further melt, leading to an irreversible tipping point.

Longer-term data like these are critical to understand how glaciers behave, and the processes and tipping points that exist within individual glaciers. These complex processes make it difficult to predict how a glacier will behave in future.

The world’s hardest jigsaw

We used satellite records to reconstruct how big the glacier was and how it behaved, but this really limits us to the past 50 years. To go back further, we need different methods. To go back 250 years, we mapped the ridges of moraines, which are large piles of debris deposited at the glacier snout, and places where glaciers have scoured and polished the bedrock.

To check and build on our mapping, we spent two weeks on the icefield itself and two weeks in the rainforest below. We camped among the moraine ridges, suspending our food high in the air to keep it safe from bears, shouting to warn off the moose and bears as we bushwhacked through the rainforest, and battling mosquitoes thirsty for our blood.

We used aerial photographs to reconstruct the icefield in the 1940s and 1970s, in the era before readily available satellite imagery. These are high-quality photos but they were taken before global positioning systems made it easy to locate exactly where they were taken.

A number also had some minor damage in the intervening years—some Sellotape, a tear, a thumbprint. As a result, the individual images had to be stitched together to make a 3D picture of the whole icefield. It was all rather like doing the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzle.

Work like this is crucial as the world’s glaciers are melting fast—all together they are currently losing more mass than the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets, and thinning rates of these glaciers worldwide has doubled over the past two decades.

Our longer time series shows just how stark this acceleration is. Understanding how and where “feedbacks” are making glaciers melt even faster is essential to make better predictions of future change in this important region![]()

Bethan Davies, Senior Lecturer in Physical Geography, Newcastle University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alaska’s top-heavy glaciers are approaching an irreversible tipping point Read More »