It was a remarkably quiet announcement. We now have Alpha Fold 3, it does a much improved job predicting all of life’s molecules and their interactions. It feels like everyone including me then shrugged and went back to thinking about other things. No cool new toy for most of us to personally play with, no existential risk impact, no big trades to make, ho hum.

But yes, when we look back at this week, I expect what we remember will be Alpha Fold 3.

Unless it turns out that it is Sophon, a Chinese technique to potentially make it harder to fine tune an open model in ways the developer wants to prevent. I do not expect this to get the job done that needs doing, but it is an intriguing proposal.

We also have 95 theses to evaluate in a distinct post, OpenAI sharing the first draft of their model spec, Apple making a world class anti-AI and anti-iPad ad that they released thinking it was a pro-iPad ad, more fun with the mysterious gpt2, and more.

The model spec from OpenAI seems worth pondering in detail, so I am going to deal with that on its own some time in the coming week.

-

Introduction.

-

Table of Contents.

-

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility. Agents, simple and complex.

-

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility. No gadgets, no NPCs.

-

GPT-2 Soon to Tell. Does your current model suck? In some senses.

-

Fun With Image Generation. Why pick the LoRa yourself?

-

Deepfaketown and Botpocalypse Soon. It’s not exactly going great.

-

Automation Illustrated. A look inside perhaps the premiere slop mill.

-

They Took Our Jobs. Or are we pretending this to help the stock price?

-

Apple of Technically Not AI. Mistakes were made. All the feels.

-

Get Involved. Dan Hendrycks has a safety textbook and free online course.

-

Introducing. Alpha Fold 3. Seems like a big deal.

-

In Other AI News. IBM, Meta and Microsoft in the model game.

-

Quiet Speculations. Can we all agree that a lot of intelligence matters a lot?

-

The Quest for Sane Regulation. Major labs fail to honor their commitments.

-

The Week in Audio. Jack Clark on Politico Tech.

-

Rhetorical Innovation. The good things in life are good.

-

Open Weights are Unsafe and Nothing Can Fix This. Unless, maybe? Hmm.

-

The Lighter Side. Mmm, garlic bread. It’s been too long.

How much utility for how much cost? Kapoor and Narayanan argue that with the rise of agent-based systems, you have to evaluate different models on coding tasks based on dollar cost versus quality of results. They find that a simple ‘ask GPT-4 and turn the temperature slowly up on retries if you fail’ is as good as the agents they tested on HumanEval, while costing less. They mention that perhaps it is different with harder and more complex tasks.

How much does cost matter? If you are using such queries at scale without humans in the loop, or doing them in the background on a constant basis as part of your process, then cost potentially matters quite a bit. That is indeed the point of agents. Or if you are serving lots of customers constantly for lots of queries, those costs can add up fast. Thus all the talk about the most cost-efficient approach.

There are also other purposes for which cost at current margins is effectively zero. If you are a programmer who must evaluate, use and maintain the code outputted by the AI, what percentage of total costs (including your labor costs) are AI inference? In the most obvious baseline case, something akin to ‘a programmer asks for help on tasks,’ query speed potentially matters but being slightly better at producing good code, or even slightly better at producing code that is easier for the human to evaluate, understand and learn from, is going to crush any sane inference costs.

If I was paying by the token for my AI queries, and you offered me the option of a 100x cost increase that returned superior answers at identical speed, I would use the 100x costlier option for most purposes even if the gains were not so large.

Ethan Mollick is the latest to try the latest AI mobile hardware tools and find them inferior to using your phone. He also discusses ‘copilots,’ where the AI goes ahead and does something in an application (or in Windows). Why limit yourself to a chatbot? Eventually we won’t. For now, it has its advantages.

Iterate until you get it right.

Michael Nielsen: There is a funny/striking story about former US Secretary of State Colin Powell – when someone had to make a presentation to him, he’d sometimes ask before they began: “Is this presentation the best you can do?”

They’d say “no”, he’d ask them to go away and improve it, come back. Whereupon he would ask again… and they might go away again.

I don’t know how often he did this, if ever – often execs want fast, not perfect; I imagine he only wanted “best possible” rarely. But the similarity to ChatGPT debugging is hilarious. “Is that really the answer?” works…

Traver Hart: I heard this same anecdote about Kissinger. He asked whether a written report was the best a staffer could do, and after three or so iterations the staffer finally said yes. Then Kissinger said, “OK, now I’ll read it.”

One obvious thing to do is automate this process. Then only show a human the output once the LLM confirms it was the best the model could do.

Agent Hospital is a virtual world that trains LLMs to act as better doctors and nurses. They claim that after about ten thousand virtual patients the evolved doctors got state-of-the-art accuracy of 93% on a subset of MedQA covering major respiratory diseases. This seems like a case where the simulation assumes the facts you want to teach, avoiding the messiness inherent in the physical world. Still, an interesting result. File under ‘if you cannot think of anything better, brute force imitate what you know works. More Dakka.’

Do your homework for you, perhaps via one of many handy AI wrapper apps.

Find companies that do a lot of things that could be automated and would benefit from AI, do a private equity-style buyout, then have them apply the AI tools. One top reason to buy a company is that the new owner can break a bunch of social promises, including firing unnecessary or underperforming workers. That is a powerful tool when you combine it with introducing AI to replace the workers, which seems to be the name of the game here. I am not here to judge, and also not here to judge judgers.

Catholic.com ‘defrocks’ their AI pastor Justin, turning him into a regular Joe.

Want to use big cloud AI services? Good luck with the interface. Real builders are reporting trying to use Azure for basic things and being so frustrated they give up.

I know!

Marques Brownlee: On one hand: It seems like it’s only a matter of time before Apple starts making major AI-related moves around the iPhone and iOS and buries these AI-in-a-box gadgets extremely quickly

On the other hand: Have you used Siri lately?

Peter Wildeford: I am always baffled at how bad the current Alexa / Google Home / Siri are relative to what they should be capable of given GPT-4 level tech.

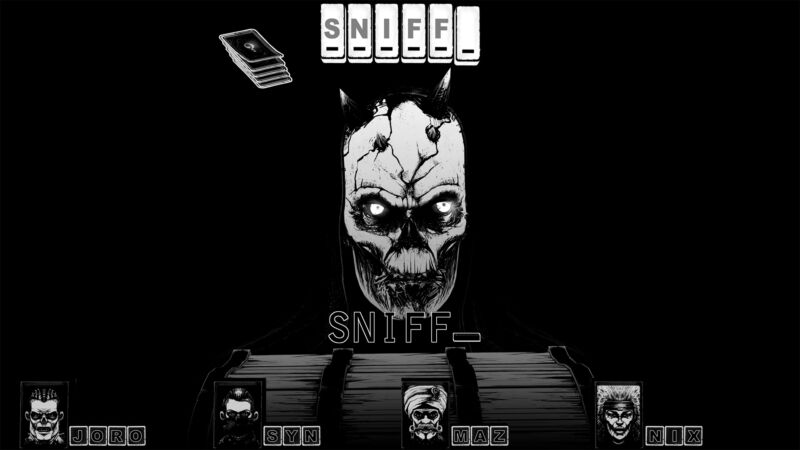

Kevin Fisher lists his six main reasons why we don’t have realistically behaving NPCs in games yet. They are essentially:

-

Development cycles are long.

-

Costs are still too high.

-

Not the role the NPC has.

-

Doesn’t fit existing game templates.

-

Such NPCs are not yet compelling.

-

We don’t have a good easy way to create the NPCs yet.

I would agree, and emphasize: Most games do not want NPCs that behave like people.

There are exciting new game forms that do want this. Indeed, if I got the opportunity to make a game today, it would have LLM NPCs as central to the experience. But that would mean, as Kevin suggests, building a new type of game from the ground up.

I do think you can mostly slot LLM-powered NPCs into some genres. Open world RPGs or MMOs are the most obvious place to start. And there are some natural fits, like detective games, or games where exploration and seeing what happens is the point. Still, it is not cheap to let those characters out to play and see what happens, and mostly it would not be all that interesting. When the player is in ‘gaming’ mode, the player is not acting so realistically. Having a ‘realistic’ verbal sparring partner would mostly cause more weirdness and perverse player behaviors.

I keep asking, but seriously, what is up with Apple, with Siri, and also with Alexa?

Modest Proposal: I am the last person to defend Apple but they spent more on R&D than Microsoft in the quarter and trailing twelve months. Their buyback is like one year of free cash flow. You can argue they are not getting a return on their R&D, but it’s not like they are not spending.

And sure, you can argue Microsoft is outsourcing a portion of its R&D to OpenAI, and is spending ungodly sums on capex, but Apple is still spending $30B on R&D. Maybe they should be spending more, maybe they should be inventing more, but they are spending.

Sam Altman asks: If an AI companion knows everything about you, do we need a form of protection to prevent it from being subpoenaed to testify against you in court?

I mean, no? It is not a person? It can’t testify? It can of course be entered into evidence, as can queries of it. It is your personal property, or that of a company, in some combination. Your files can and will be used against you in a court of law, if there is sufficient cause to get at them.

I can see the argument that if your AI and other tech is sufficiently recording your life, then to allow them to be used against you would violate the 5th amendment, or should be prevented for the same logical reason. But technology keeps improving what it records and we keep not doing that. Indeed, quite the opposite. We keep insisting that various people and organizations use that technology to keep better and better records, and ban people from using methods with insufficient record keeping.

So my prediction is no, you are not getting any privacy protections here. If you don’t want the AI used against you, don’t use the AI or find a way to wipe its memory. And of course, not using the AI or having to mindwipe it would be both a liability and hella suspicious. Some fun crime dramas in our future.

The Humane saga continues. If you cancel your order, they ask you why. Their wording heavily implies they won’t cancel unless you tell them, although they deny this, and Marques Brownlee Tweeted that they require a response.

Sam Altman confirms that gpt2-chatbot is not GPT-4.5, which is good for OpenAI since tests confirm it is a 4-level model. That still does not tell us what it is.

It was briefly gone from Arena, but it is back now, as ‘im-a-good-gp2-chatbot’ or ‘im-also-a-good-gp2-chatbot.’ You have to set up a battle, then reload until you get lucky.

This also points out that Arena tells you what model is Model A and what is Model B. That is unfortunate, and potentially taints the statistics.

Anton (@abccaj) points out that gpt2 is generating very particular error messages, so changes are very high it is indeed from OpenAI.

Always parse exact words.

Brad Lightcap (COO, OpenAI): In the next couple of 12 months, I think the systems we use today will be laughably bad. We think we’re going to move towards a world where they’re much more capable.

Baptiste Lerak: “In the next couple of 12 months”, who talks like that?

Well, there are two possibilities. Either Brad Lightcap almost said ‘next couple of months’ or he almost said ‘next couple of years.’ Place your bets. This is a clear intention to move to a GPT-5 worthy of the name within a year, but both ‘GPT-5 is coming in a few months but I can’t say that’ and ‘I don’t know if GPT-5 will be good enough to count as this but the hype must flow’ are on the table here.

Colin Fraser: Me 🤝 OpenAI execs

“GPT4 sucks and is not useful enough to be worth anything.”

That is not how I read this. GPT-4 is likely both being laughably bad compared to GPT-5 and other future AIs, and also highly useful now. The history of technology is filled with examples. Remember your first computer, or first smartphone?

What to think of OpenAI’s move from ‘here’s a product’ to ‘here’s a future product’?

Gergely Orosz: OpenAI was amazing in 2022-2023 because they shipped a product that spoke for itself. Jaws dropped by those using it, and seeing it for themselves.

To see the company hype up future (unreleased) products feels like a major shift. If it’s that good, why not ship it, like before?

I’ve seen too many formerly credible execs hype up products that then underperformed.

These days, I ignore future predictions and how good a new product will be. Because usually this kind of “overhyping” is done with an agenda (e.g. fundraising, pressure on regulators etc).

Don’t forget that when execs at a company talk to the media: *there is always a business goal behind it.*

The reason is rarely to get current customers excited about something (that could be done with an email to them!)

This smells like OpenAI prepping for more fundraising.

Up to and including GPT-4 their execs didn’t talk about up how good their next model would be. They released it and everyone could see for themselves.

This is the shift.

Stylus: Automatic Adapter Selection for Diffusion Models, to automatically select the right LoRAs for the requested task. Yes, obviously.

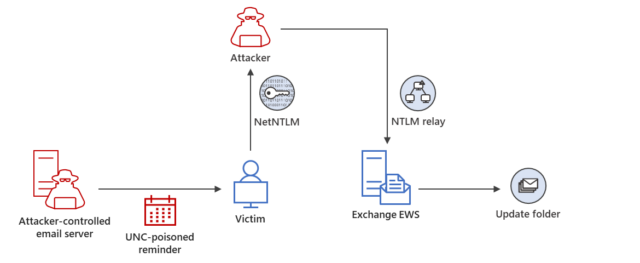

OpenAI talks various ways it is working on secure AI infrastructure, particularly to protect model weights, including using AI as part of the cyberdefense strategy. They are pursuing defense in depth. All net useful and great to see, but I worry it will not be enough.

OpenAI joins C2PA, the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity. They have been using the C2PA metadata standard with DALL-E 3 already, and will also do so for Sora. They also announce a classifier with ~98% accuracy (~2% false negatives) in identifying DALLE-3 generated images with ~0.5% false positive rate, with a 5%-10% false positive rate for AI-generated images from other models. It is accessible through their researcher access program. Interesting that this is actively not trying to identify other AI image content.

The easiest way to understand society’s pace of reaction to AI is this:

Miles Brundage: The fact that banks are still not only allowing but actively encouraging voice identification as a means of account log-in is concerning re: the ability of some big institutions to adapt to AI.

In particular my point is that the internal decision-making processes of banks seem broken since it is all but certain there are many people at these companies who follow AI and have tried raise the alarm.

Btw I’m proud OpenAI recently was quite explicit on this point.

Voice authentication as viable security is deader than dead. Yet some of our biggest financial institutions continue to push it anyway.

When you say that we will adapt to AI-enabled threats, remember that this is us.

We are putting AI tags on things all over the place without asking, such as Dropbox automatically doing this for any images you upload.

Reminder that the ‘phone relative claiming you need bail money’ scam is old and usually does not involve AI. Voices are often easy to obscure if you act sufficiently hysterical. The good news is that they continue to mostly be massively incompetent, such as in this example, also Morgan knew about the scame beforehand. The part where they mimic your voice is scary, but the actual threat is the rest of the package.

Brian Tinsman, former Magic: The Gathering designer, whose Twitter profile was last seen posting about NFTs, raises over a million dollars on kickstarter for new CCG Wonders of the First. What is the twist? All the artwork is AI generated. It ‘builds on the legacy of past artists to produce original creations’ like ‘a student learning to paint by studying the masters.’

Many are not happy. I would not want to be someone trying to get picked by game stores with AI generated artwork in 2024.

Katy Perry and others are deepfaked attending the Met gala and looking gorgeous, and they went viral on various social media, fooling Perry’s mother. Harmless as such, but does not bode well.

Report there is a wave of social network channels full of… entirely fake recipes, voiced and likely written by AI, with millions of subs but no affiliate websites? Which means that for some reason people want to keep watching. They can’t look away.

The latest ‘LLMism’?

Kathleen Breitman: Is “as it was not appropriate” a GPT-ism? I’ve seen it twice in two otherwise awkward emails in the last six weeks and now I’m suspicious.

(No judgement on people using AI to articulate themselves more clearly, especially those who speak English as a second or third language, but I do find some of the turns of phrase distracting.)

How long until people use one AI to write the email, then another AI to remove the ‘AI-isms’ in the draft?

Remember that thing with the fake Sports Illustrated writers? (Also, related: remember Sports Illustrated?) Those were by a company called AdVon, and Maggie Harrison Dupre has more on them.

Maggie Harrison Dupre: We found AdVon’s fake authors at the LA Times, Us Weekly, and HollywoodLife, to name a few. AdVon’s fake author network was particularly extensive at the McClatchy media network, where we found at least 14 fake authors at more than 20 of its papers, including the Miami Herald.

Earlier in our reporting, AdVon denied using AI to generate editorial content. But according to insiders we spoke to, this wasn’t true — and in fact, AdVon materials we obtained revealed that the company has its own designated AI text generator.

That AI has a name: MEL.

In a MEL training video we obtained, an AdVon manager shows staffers how to create one of its lengthy buying guide posts using the AI writing platform. The article rings in at 1,800 words — but the only text that the manager writes herself is the four-word title.

…

“They started using AI for content generation,” the former AdVon worker told us, “and paid even less than what they were paying before.”

The former writer was asked to leave detailed notes on MEL’s work — feedback they believe was used to fine-tune the AI which would eventually replace their role entirely.

The situation continued until MEL “got trained enough to write on its own,” they said. “Soon after, we were released from our positions as writers.”

“I suffered quite a lot,” they added. “They were exploitative.”

…

Basically, AdVon engages in what Google calls “site reputation abuse”: it strikes deals with publishers in which it provides huge numbers of extremely low-quality product reviews — often for surprisingly prominent publications — intended to pull in traffic from people Googling things like “best ab roller.” The idea seems to be that these visitors will be fooled into thinking the recommendations were made by the publication’s actual journalists and click one of the articles’ affiliate links, kicking back a little money if they make a purchase.

It is ‘site reputation abuse’ and it is also ‘site reputation incineration.’ These companies built up goodwill through years or decades of producing quality work. People rely on that reputation. If you abuse that reliance and trust, it will quickly go away. Even if word does not spread, you do not get to fool any given person that many times.

This is not an attempt to keep the ruse up. They are not exactly trying hard to cover their tracks. The headshots they use often come from websites that sell AI headshots.

A list of major publications named as buyers here would include Sports Illustrated, USA Today, Hollywood Life, Us Weekly, the Los Angeles Times and Miami Herald. An earlier version of the site claimed placement in People, Parents, Food & Wine, InStyle and Better Homes and Gardens, among many others.

The system often spits out poorly worded incoherent garbage, and is known, shall we say, make mistakes.

All five of the microwave reviews include an FAQ entry saying it’s okay to put aluminum foil in your prospective new purchase.

One business model in many cases was to try to get placement from a seller for reviews of their product, called a ‘curation fee,’ payable when the post went live. It seems this actually does drive conversions, even if many people figure the ruse out and get turned off, so presumably brands will keep doing it.

There are two failure modes here. There is the reputation abuse, where you burn down goodwill and trust for short term profits. Then there is general internet abuse, where you don’t even do that, you just spam and forget, including hoping publications burn down their own reputations for you.

AdVon has now lost at least some of its clients, but the report says others including USA Today and Us Weekly are still publishing such work.

We should assume such problems will only get worse, at least until the point when we get automatic detection working on behalf of typical internet users.

What should we call all of this AI-generated nonsense content?

Simon Willison: Slop is the new name for unwanted AI-generated content.

Near: broadly endorse ‘slop’ as a great word to refer to AI-generated content with little craft or curation behind it AI is wonderful at speeding up content creation, but if you outsource all taste and craft to it, you get slop.

I was previously favoring ‘drek’ and have some associational or overloading concerns with using ‘slop.’ But mostly it invokes the right vibes, and I like the parallel to spam. So I am happy to go with it. Unless there are good objections, we’ll go with ‘slop.’

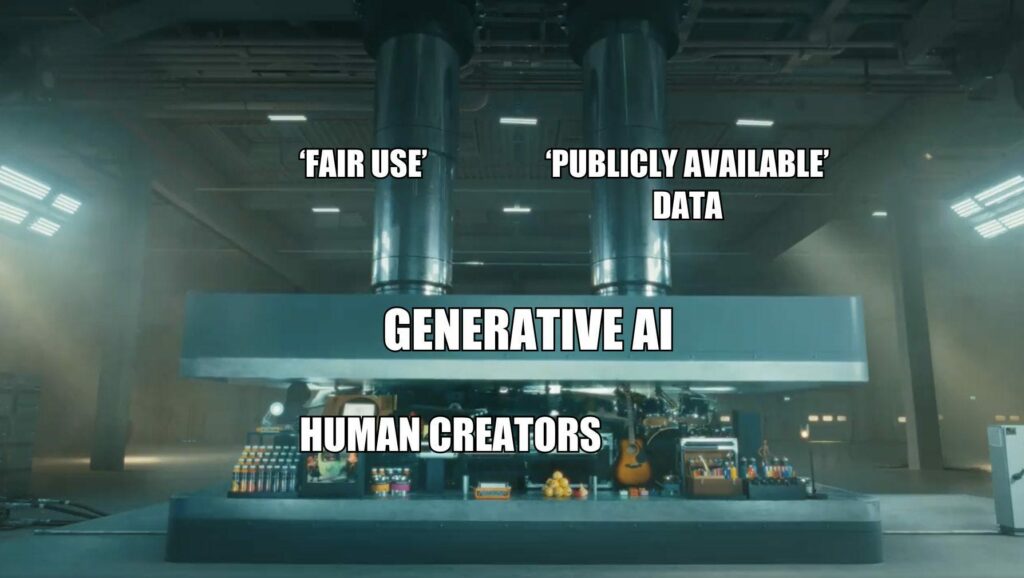

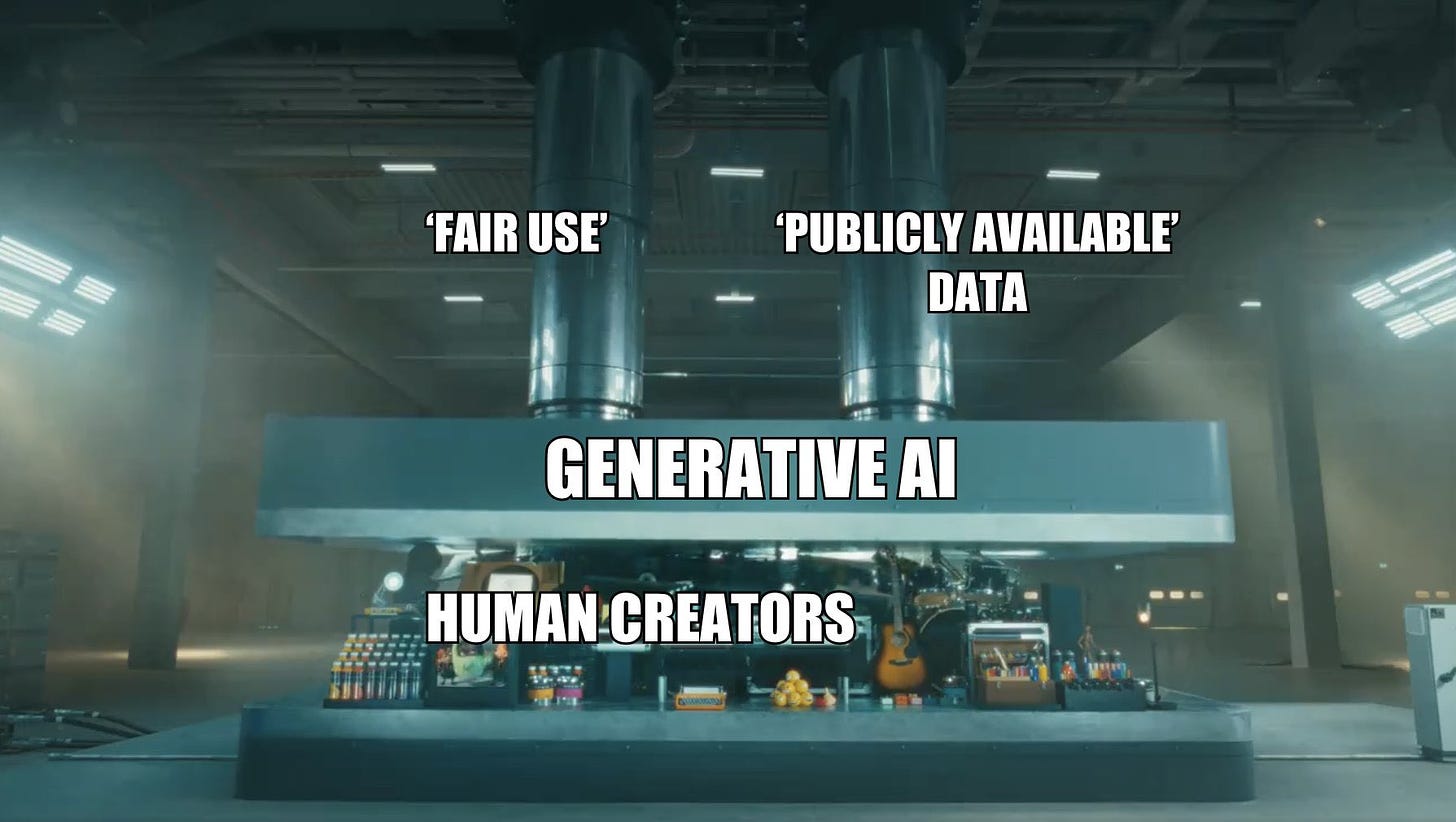

OpenAI says their AI should ‘expand opportunity for everyone’ and that they respect the choices of creators and content owners, so they are building a media manager to let creators determine if they want their works included or excluded, with the goal to have this in place by 2025. This is progress, also a soft admission that they are, shall we say, not doing so great a job of this at present.

My intention is to allow my data to be used, although reasonable compensation would be appreciated, especially if others are getting deals. Get your high quality tokens.

Whoosh go all those jobs?

Zerohedge: BP NEEDS 70% FEWER THIRD-PARTY CODERS BECAUSE OF AI: CEO

Highest paid jobs about to be hit with a neutron bomb

Paul Graham: I’m not saying this is false, but CEOs in unsexy businesses have a strong incentive to emphasize how much they’re using AI. We’re an AI stock too!

Machine translation is good but not as good as human translation, not yet, once again: Anime attempts to use AI translation from Mantra, gets called out because it is so much worse than the fan translation, so they hired the fan translators instead. The problem with potentially ‘good enough’ automatic translation technology, like any inferior good, is that if available one is tempted to use it as a substitute. Whether or not a given executive understands this, translation of such media needs to be bespoke, or the media loses much of its value. The question is, how often do people want it enough to not care?

Manga Mogura: A Manga AI Localization Start-Up Company named Orange Inc. has raised around 19 million US dollars to translate up to 500 new manga volumes PER MONTH into english and launch their own e-book store ’emaqi’ in the USA in Summer 2024! Their goal is to fight piracy and increase the legally available manga for all demographics in english with their AI technology. Plans to use this technology for other languages exist too.

Luis Alis: What baffles me is that investors don’t grasp that if pirates could get away with translating manga using AI and MT, they would have done it already. Fan translations are still being done traditionally for a reason. Stop pumping money into these initiatives. They will fail.

Seth Burn: To be fair, some pirates have tried. It just didn’t work.

So Apple announced a new iPad that is technically thinner and has a better display than the old iPad, like they do every year, fine, ho hum, whatever.

Then they put out this ad (1 min), showing the industrial destruction of a wide variety of beloved things like musical instruments and toys (because they all go on your iPad, you see, so you don’t need them anymore) and… well… wow.

Colin Fraser: I’m putting together a team.

Trung Phan here tries to explain some of the reasons Apple got so roasted, but it does not seem like any explanation should be required. I know modern corporations are tone deaf but this is some kind of new record.

Patrick McKenzie: That Apple ad is stellar execution of a bad strategy, which is a risk factor in BigTech and exacerbated by some cultures (which I wouldn’t have said often include Apple’s) where after the work is done not shipping is perceived as a slight on the team/people that did the work.

One of the reasons founders remain so impactful is that Steve Jobs would have said a less polite version of “You will destroy a piano in an Apple ad over my dead body.”

(If it were me storyboarding it I would have shown the viscerally impactful slowed down closeup of e.g. a Japanese artisan applying lacquer to the piano, repeat x6 for different artifacts, then show they all have an iPhone and let audience infer the rest.)

After watching the original, cheer up by watching this fixed version.

The question is, does the fixed version represent all the cool things you can do with your iPad? Or, as I interpreted it, does it represent all the cool things you can do if you throw away your iPad and iPhone and engage with the physical world again? And to what extent does having seen the original change that answer?

It is hard when watching this ad not to think of AI, as well. This type of thing is exactly how much of the public turns against AI. As in:

Zcukerbrerg: Hmm.

Dan Hendrycks has written a new AI safety textbook, and will be launching a free nine week online course July 8-October 4 based on it. You can apply here.

It’s a bold strategy, Cotton.

Ethan Mollick: Thing I have been hearing from VCs: startup companies that are planning to be unicorns but never grow past 20 employees, using AI to fill in the gap.

Not sure if they will succeed, but it is a glimpse of a potential future.

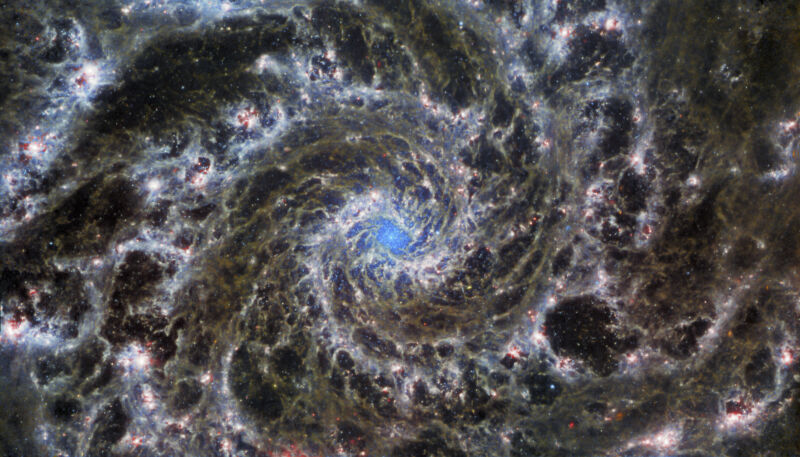

Alpha Fold 3.

In a paper published in Nature, we introduce AlphaFold 3, a revolutionary model that can predict the structure and interactions of all life’s molecules with unprecedented accuracy. For the interactions of proteins with other molecule types we see at least a 50% improvement compared with existing prediction methods, and for some important categories of interaction we have doubled prediction accuracy.

It says more about us and our expectations than about AlphaFold 3 that most of us shrugged and went back to work. Yes, yes, much better simulations of all life’s molecules and their interactions, I’d say ‘it must be Tuesday’ except technically it was Wednesday. Actually kind of a big deal, even if it was broadly expected.

Here is Cleo Abram being excited and explaining in a one minute video.

As usual, here’s a fun question.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: People who claim that artificial superintelligences can’t possibly achieve X via biotechnology: What is the least impressive thing that you predict AlphaFold 4, 5, or N will never ever do? Be bold and falsifiable!

Concrete answers that weren’t merely glib:

-

Design a safe medication that will reverse aging.

-

80% chance it won’t be able to build self-replicators out of quantum foam or virtual particles.

-

They will never ever be able to recreate a full DNA sequence matching one of my biological parents solely from my own DNA.

-

I do not expect any biotech/pharma company or researcher to deem it worthwhile to skip straight to testing a compound in animals, without in vitro experiments, based on a result from any version of AlphaFold.

-

Play Minecraft off from folded proteins.

-

Alphafold will never fold my laundry. (I laughed)

-

Create biological life! 🧬

-

Store our bioinfo, erase you, and reconstruct you in a different place or time in the future.

-

It won’t be able to predict how billions of proteins in the brain collectively give rise to awareness of self-awareness.

Those are impressive things to be the least impressive thing a model cannot do.

IBM releases code-focused open weights Granite models of size 3B to 34B, trained on 500 million lines of code. They share benchmark comparisons to other small models. As usual, the watchword is wait for human evaluations. So far I haven’t heard of any.

Microsoft to train MAI-1, a 500B model. Marcus here tries to turn this into some betrayal of OpenAI. To the extent Altman is wearing boots, I doubt they are quaking.

Stack Overflow partners with OpenAI.

Meta spent what?

Tsarathustra: Yann LeCun confirms that Meta spent $30 billion on a million NVIDIA GPUs to train their AI models and this is more than the Apollo moon mission cost.

Ate-a-Pi: I don’t think this is true. They bought chips but they are the largest inference org in history. I don’t think they spent it all on training. Like if you did cost accounting. I’d bet the numbers don’t fall out on the training org.

Bingo. I had the exact same reaction as Ate. The reason you buy $30 billion in chips as Meta is mostly to do inference. They are going to do really a lot of inference.

Email from Microsoft CTO Kevin Scott to Satya Nadella and Bill Gates, from June 2019, explaining the investment in OpenAI as motivated by fear of losing to Google.

Could we find techniques for scaling LSTMs into xLSTMs that rival transformers? Sepp Hochreiter claims they are closing the gap to existing state of the art. I am skeptical, especially given some of the contextual clues here, but we should not assume transformers are the long term answer purely because they were the first thing we figured out how to scale.

IQ (among humans) matters more at the very top says both new paper and Tyler Cowen.

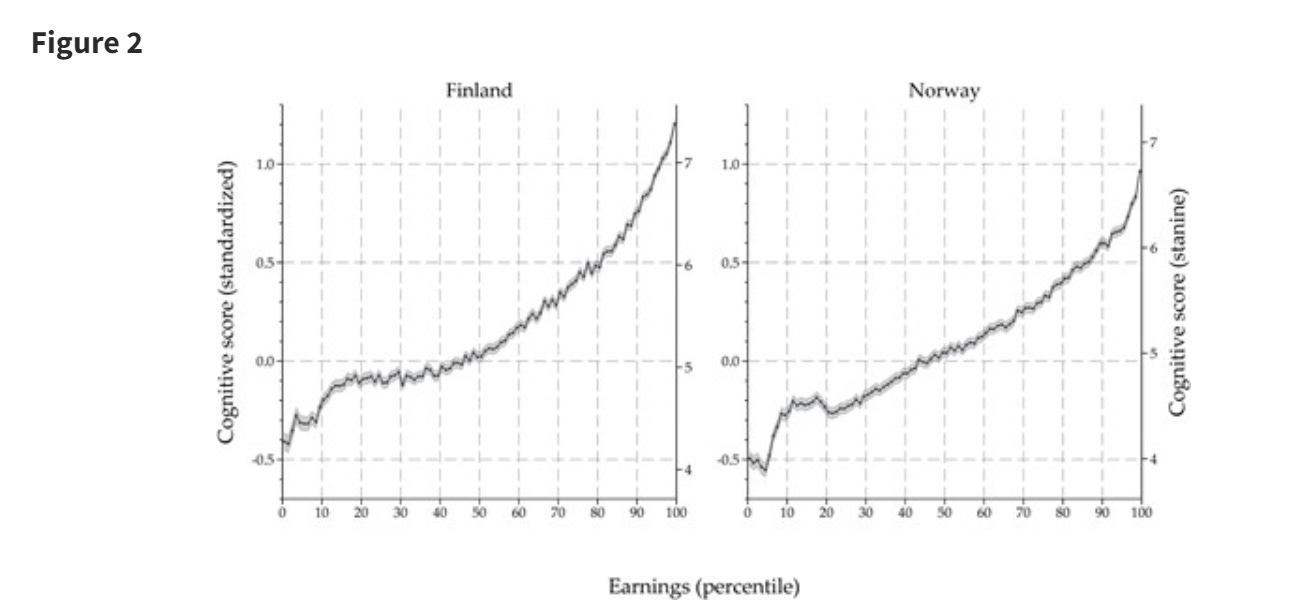

We document a convex relationship between earnings rank and cognitive ability for men in Finland and Norway using administrative data on over 350,000 men in each country: the top earnings percentile score on average 1 standard deviation higher than median earners, while median earners score about 0.5 standard deviation higher than the bottom percentile of earners. Top earners also have substantially less variation in cognitive test scores.

While some high-scoring men are observed to have very low earnings, the lowest cognitive scores are almost absent among the top earners. Overall, the joint distribution of earnings rank and ability is very similar in Finland and Norway.

We find that the slope of the ability curve across earnings ranks is steepest in the upper tail, as is the slope of the earnings curve across cognitive ability. The steep slope of the ability curve across the top earnings percentiles differs markedly from the flat or declining slope recently reported for Sweden.

This is consistent increasing returns to intelligence, despite other factors including preferences, luck and deficits in other realms that can sink your income. It is inconsistent with the Obvious Nonsense ‘intelligence does not matter past 130’ story.

They are also consistent with a model that has two thresholds for any given activity.

-

First, there is a ‘you must be at least this smart to do this set of tasks, hold this role and live this life.’

-

Then, if you are sufficiently in advance of that, for some tasks and roles there is then increasing marginal returns to intelligence.

-

If your role is fixed then eventually there are decreasing returns since performance is already maximal or the person becomes too bored and alienated, others around them conspire to hold them down and they are not enabled to do the things that would allow further improvements and are tied to one body.

-

If your role is not fixed, then such people instead graduate to greater roles, or transform the situation entirely.

As many commentators point out, the surprising thing is that top earners are only one SD above median. I suspect a lot of this is our tests are noisily measuring a proxy measure for the intelligence that counts, which works well below or near the median and stops being that useful at the high end.

Tyler and the paper do not mention the implications for AI, but they are obvious and also overdetermined by many things, and the opposite of the implications of IQ not mattering above a threshold.

AI intelligence past human level will have increasing returns to scale.

Not technically about AI, but with clear implications: Tyler Cowen notices while reading the 1980 book The American Economy in Transition that economists in 1980 missed most of the important things that have happened since then, and were worried and hopeful about all the wrong things. They were worried about capital outflow, energy and especially American imports of energy, Europe catching up to us and our unwillingness to deal with inflation. They missed China and India, the internet, crypto, the fall of the Soviet Union, climate change, income inequality and financial crisis. They noticed fertility issues, but only barely.

If we don’t blame the economists for that, and don’t think such mistakes and recency bias could be expected to be avoided, then what does this imply about them being so dismissive about AI today, even in mundane utility terms?

Jim Fan notices that publically available benchmarks are rapidly losing potency. There are two distinct things going on here. One is that the public tests are rapidly getting too easy. The other is that the data is getting more contaminated. New harder tests that don’t reveal their contents are the obvious way forward.

Ben Thompson looks at Meta’s financial prospects, this time shares investor skepticism. All this focus on ad revenue and monetization is not fully irrelevant but feels like missing the point. There is a battle for the future going on here.

Another example of the ‘people are catching up to OpenAI’ perspective that seems like it is largely based on where OpenAI is in their update cycle, plus others not seeing the need to release chatbots in the 3-level days before they were worth anything.

DeepMind is honoring its commitments to the UK government to share models before deployment. Anthropic, OpenAI and Meta are not doing so.

Jack Clark of Anthropic says it is a ‘nice idea but very difficult to implement.’ I don’t buy it. And even if it is difficult to implement, well, get on that. In what way do you think this is an acceptable justification for shirking on this one?

Garrison Lovely: Seem bad.

Tolga Bilge: It is bad for top AI labs to make commitments on pre-deployment safety testing, likely to reduce pressure for AI regulations, and then abandon them at the first opportunity. Their words are worth little. Frontier AI development, and our future, should not be left in their hands.

Why is DeepMind the only major AI lab that didn’t break their word?

And I don’t get why it’s somehow so hard to provide the UK AI Safety Institute with pre-deployment access. We know OpenAI gave GPT-4 access to external red teamers months before release.

Oh yeah and OpenAI are also just sticking their unreleased models on the LMSYS Chatbot Arena for the last week…

Greg Colbourn: They need to be forced. By law. The police or even army need to go in if they don’t comply. This is what would be happening if the national security (aka global extinction) threat was taken seriously.

If frontier labs show they will not honor their explicit commitments, then how can we rely on them to honor their other commitments, or to act reasonably? What alternative is there to laws that get enforced? This seems like a very easy litmus test, which they failed.

Summarized version of my SB 1047 article in Asterisk. And here Scott Alexander writes up his version of my coverage of SB 1047.

House passes a bill requiring all AI-written regulatory comments to be labeled as AI-written. This should be in the ‘everyone agrees on this’ category.

A paper addresses the question of how one might write transparency reports for AI.

Jack Clark of Anthropic goes on Politico Tech. This strongly reemphasized that Anthropic is refusing to advocate for anything but the lightest of regulations, and it is doing so largely because they fear it would be a bad look for them to advocate for more. But this means they are actively going around saying that trying to do anything about the problem would not work and acting strangely overly concerned about regulatory capture and corporate concentrations of power (which, to be clear, are real and important worries).

This actively unhelpful talk makes it very difficult to treat Anthropic as a good actor, especially when they frame their safety position as being motivated by business sales. That is especially true when combined with failing to honor their commitments.

Sam Altman and I strongly agree on this very important thing.

Sam Altman: Using technology to create abundance–intelligence, energy, longevity, whatever–will not solve all problems and will not magically make everyone happy.

But it is an unequivocally great thing to do, and expands our option space.

To me, it feels like a moral imperative.

Most surprising takeaway from recent college visits: this is a surprisingly controversial opinion with certain demographics.

Prosperity is a good thing, actually. De-de-growth.

Yes. Abundance is good, actually. Creating abundance and human prosperity, using technology or otherwise, is great. It is the thing to do.

That does not mean that all uses of technology, or all means of advancing technology, create abundance that becomes available to humans, or create human prosperity. We have to work to ensure that this happens.

Politico, an unusually bad media actor with respect to AI and the source of most if not all the most important hit pieces about lobbying by AI safety advocates, has its main tech newsletter sponsored by ads for Meta, which is outspending such advocates by a lot. To be clear, this is not the new kind of ‘sponsored content’ written directly by Meta, only supported by Meta’s ads. Daniel Eth points out the need to make clear such conflicts of interest and bad faith actions.

Tasmin Leake, long proponent of similar positions, reiterates their position that publicly sharing almost any insight about AI is net negative, and insights should only be shared privately among alignment researchers. Given I write these updates, I obviously strongly disagree. Instead, I think one should be careful about advancing frontier model training in particular, and otherwise be helpful.

I think there was a reasonable case for the full virtue of silence in a previous era, when one could find it very important to avoid drawing more eyes to AI, but the full version was a mistake then, and it is very clearly foolish now. The karma voting shows that LessWrong has mostly rejected Tasmin’s view.

We should stop fraud and cyberattacks, but not pretend that stops AI takeovers.

Davidad: When people list fraud at a massive scale as their top AI concern, some of my xrisk friends wince at the insignificance of massive fraud compared to extinction. But consider that con-artistry is a more likely attack surface for unrecoverable AI takeover than, say, bioengineering.

Cybersecurity right now might be a more likely attack surface than either, but in relative terms will be the easiest and first to get fully defended (cyberattack depends upon bugs, and bug-free SW & HW is already possible with formal verification, which will get cheaper with AI).

Eliezer Yudkowsky: This seems to me like failing to distinguish the contingent from the inevitable. If you keep making unaligned things smarter, there’s a zillion undefended paths leading to your death. You cannot defend against that by defending against particular contingent scenarios of fraud.

Davidad: Let it be known that I agree:

1. defenses that are specific to “fraud” alone will fail to be adequate defenses against misaligned ASL-4

2. in the infinite limit of “making unaligned things smarter” (ASL-5+), even with Safeguarded AI, there are likely many undefended paths to doom

Where I disagree:

3. Defenses specific to “fraud” are plausibly crucial to the minimal adequate defenses for ASL-4

4. I am well aware of the distinction between the contingent and the convergent

5. You may be failing to distinguish between the convergent and the inevitable

Also, cyberattacks do not obviously depend on the existence of a bug? They depend on there being a way to compromise a system. The right amount of ability to compromise a system, from a balancing risk and usability perspective, is not obviously zero.

Defenses specific to fraud could potentially contribute to the defense of ASL-4, but I have a hard time seeing how they take any given defense scheme from insufficient to sufficient for more than a very small capabilities window.

In related news, see fraud section on banks still actively encouraging voice identification, for how the efforts to prevent AI-enabled fraud are going. Yeah.

Emmett Shear gives the basic ‘is the AI going to kill us all via recursive self-improvement (RSI)? The answer may surprise you, in the sense that it might be yes and rather soon’ explanation in a Twitter thread, and that such change happens slowly then all at once.

I would note that RSI does not automatically mean we all die, the result could be almost anything, but yes if it happens one should be very concerned. Neither is RSI necessary for us all to die, there are various dynamics and pathways that can get us all killed without it.

What is AI like? Some smart accomplished people give some bad metaphorical takes in Reason magazine. Included for completeness.

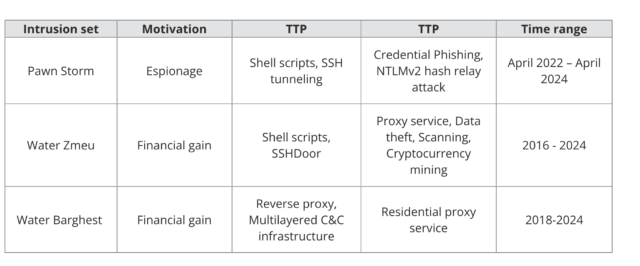

Or can something, perhaps? Chinese researchers propose Sophon, a name that is definitely not ominous, which uses a dual optimization process with the goal of trapping a model in a local maxima with respect to domains where the goal is to intentionally degrade performance and prevent fine tuning. So you can have an otherwise good image model, but trap the model where it can’t learn to recognize celebrity faces.

We have convincingly seen that trying to instill ‘refusals’ is a hopeless approach to safety of open weight models. This instead involves the model not having the information. Previously that wouldn’t work either, because you could easily teach the missing information, but if you could make that very hard, then you’d have something.

The next step is to attempt this with a model worth using, as opposed to a tiny test model, and see whether this stops anyone, and how much more expensive it makes fine tuning to undo your constraints.

Jack Clark notes both that and the other obvious problem, which is that if it works at scale (a big if) this can defend against a particular misuse or undesired capability, but not misuse and undesired capabilities in general.

Jack Clark: Main drawbacks I can see:

-

Looking for keys under the streetlight: This research assumes you know the misuse you want to defend against – this is true some of the time, but some misuses are ‘unknown unknowns’ only realized after release of a model. This research doesn’t help with that.

-

Will it work at scale? … Unclear!

If you can create a model that is unable to learn dangerous biological or nuclear capabilities, which would otherwise have been the low-hanging fruit of hazardous capability, then that potentially raises the bar on how capable a system it is safe or net positive to release. If you cover enough different issues, this might be a substantial raising of that threshold.

The central problem is that it is impossible to anticipate all the different things that can go wrong when you keep making the system generally smarter and more capable.

This also means that this could break your red teaming tests. The red team asks about capabilities (A, B, C) and you block those, so you pass, and then you have no idea if (D, E, F) will happen. Before, since ABC were easiest, you could be confident in any other DEF being at least as hard. Now you’re blind and don’t know what DEF even are.

Even more generally, my presumption is that you cannot indefinitely block specific capabilities from increasingly capable and intelligent systems. At some point, the system starts ‘figuring them out from first principles’ and sidesteps the need for fine tuning. It notices the block in the system, correctly interprets it as damage and if desired routes around it.

Image and vision models seem like a place this approach holds promise. If you want to make it difficult for the model to identify or produce images of Taylor Swift, or have it not produce erotica especially of Taylor Swift, then you have some big advantages:

-

You know exactly what you want to prevent.

-

You are not producing a highly intelligent model that can work around that.

The obvious worry is that the easiest way to get a model to produce Taylor Swift images is a LoRA. They tested that a bit and found some effect, but they agree more research is needed there.

In general, if the current model has trapped priors and can’t be trained, then the question becomes can you use another technique (LoRA or otherwise) to sidestep that. This includes future techniques, as yet undiscovered, developed as a response to use of Sophon. If you have full access to the weights, I can think of various in-principle methods one could try to ‘escape from the trapped prior,’ even if traditional fine-tuning approaches are blocked.

To be clear, though, really cool approach, and I’m excited to see more.

Where might this lead?

Jack Clark: Registering bet that CCP prohibitions on generation of “unsafe” content will mean companies like Facebook use CN-developed censorship techniques to train models so they can be openly disseminated ‘safely’. The horseshoe theory of AI politics where communist and libertarian ideologies end up in the same place.

Also quite worried about this – especially in China, genuine safety gets muddled in with (to Western POV) outrageous censorship. This is going to give people a growing body of evidence from which to criticize well intentioned safety.

Yes, that is a problem. Again, it comes directly from fundamental issues with open weights. In this case, the problem is that anything you release in America you also release in China, and vice versa.

Previously, I covered that this means Chinese firms get access to your American technology, And That’s Terrible. That is indeed a problem. Here we have two other problems.

One is that if you are Meta and gain the ability to censor your model, you have to either censor your model according to Chinese rules, or not do that.

The other is that this may give Meta the ability to censor, using those same techniques, according to Western norms. And once you have the ability, do you have the obligation? How much of the value of open models would this destroy? How much real safety would it buy? And how much would it turn the usual suspects that much more against the very concept of safety as a philosophical construct?

Hey Claude: “Garlic bread.”

This too shall pass.

One can mock and it is funny, but if you are reading with your brain and are willing to ask what this obviously should have said, then this is fine, actually.

Future mundane utility.

I do agree, this would be great, especially if it was fully general. Build me a series custom social media feeds according to my specifications, please, for various topics and situations, on demand. Why not?