We asked four AI coding agents to rebuild Minesweeper—the results were explosive

How do four modern LLMs do at re-creating a simple Windows gaming classic?

Which mines are mine, and which are AI? Credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

The idea of using AI to help with computer programming has become a contentious issue. On the one hand, coding agents can make horrific mistakes that require a lot of inefficient human oversight to fix, leading many developers to lose trust in the concept altogether. On the other hand, some coders insist that AI coding agents can be powerful tools and that frontier models are quickly getting better at coding in ways that overcome some of the common problems of the past.

To see how effective these modern AI coding tools are becoming, we decided to test four major models with a simple task: re-creating the classic Windows game Minesweeper. Since it’s relatively easy for pattern-matching systems like LLMs to play off of existing code to re-create famous games, we added in one novelty curveball as well.

Our straightforward prompt:

Make a full-featured web version of Minesweeper with sound effects that

1) Replicates the standard Windows game and

2) implements a surprise, fun gameplay feature.Include mobile touchscreen support.

Ars Senior AI Editor Benj Edwards fed this task into four AI coding agents with terminal (command line) apps: OpenAI’s Codex based on GPT-5, Anthropic’s Claude Code with Opus 4.5, Google’s Gemini CLI, and Mistral Vibe. The agents then directly manipulated HTML and scripting files on a local machine, guided by a “supervising” AI model that interpreted the prompt and assigned coding tasks to parallel LLMs that can use software tools to execute the instructions. All AI plans were paid for privately with no special or privileged access given by the companies involved, and the companies were unaware of these tests taking place.

Ars Senior Gaming Editor (and Minesweeper expert) Kyle Orland then judged each example blind, without knowing which model generated which Minesweeper clone. Those somewhat subjective and non-rigorous results are below.

For this test, we used each AI model’s unmodified code in a “single shot” result to see how well these tools perform without any human debugging. In the real world, most sufficiently complex AI-generated code would go through at least some level of review and tweaking by a human software engineer who could spot problems and address inefficiencies.

We chose this test as a sort of simple middle ground for the current state of AI coding. Cloning Minesweeper isn’t a trivial task that can be done in just a handful of lines of code, but it’s also not an incredibly complex system that requires many interlocking moving parts.

Minesweeper is also a well-known game, with many versions documented across the Internet. That should give these AI agents plenty of raw material to work from and should be easier for us to evaluate than a completely novel program idea. At the same time, our open-ended request for a new “fun” feature helps demonstrate each agent’s penchant for unguided coding “creativity,” as well as their ability to create new features on top of an established game concept.

With all that throat-clearing out of the way, here’s our evaluation of the AI-generated Minesweeper clones, complete with links that you can use to play them yourselves.

Agent 1: Mistral Vibe

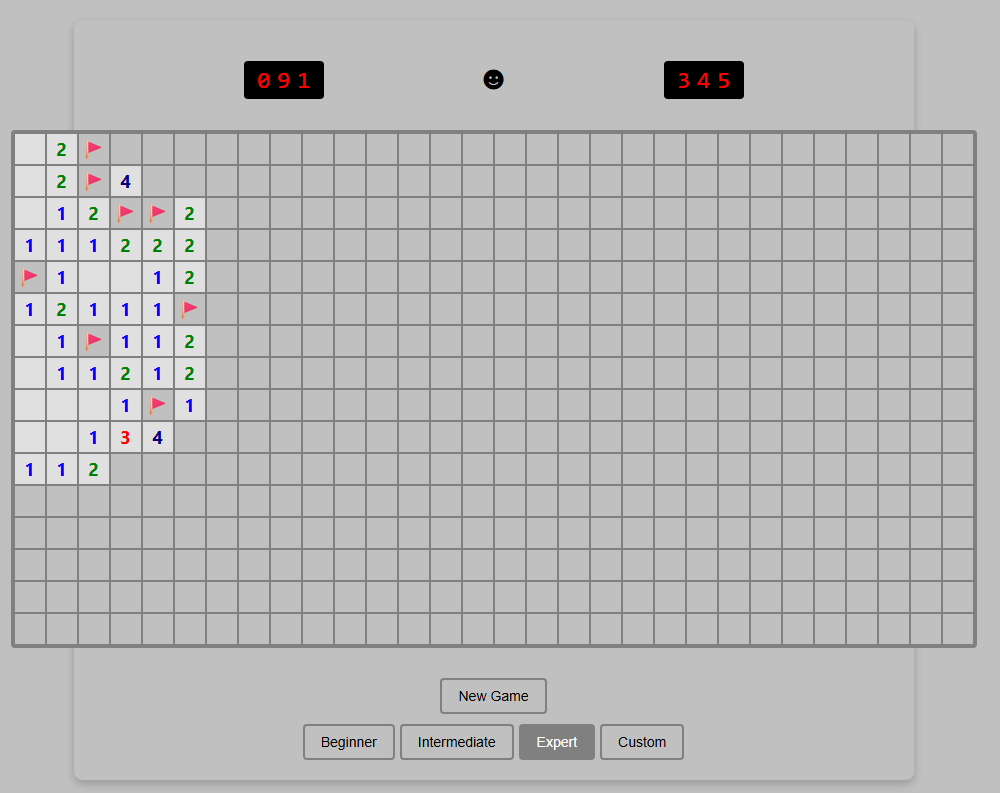

Just ignore that Custom button. It’s purely for show. Credit: Benj Edwards

Implementation

Right away, this version loses points for not implementing chording—the technique that advanced Minesweeper players use to quickly clear all the remaining spaces surrounding a number that already has sufficient flagged mines. Without this feature, this version feels more than a little clunky to play.

I’m also a bit perplexed by the inclusion of a “Custom” difficulty button that doesn’t seem to do anything. It’s like the model realized that customized board sizes were a thing in Minesweeper but couldn’t figure out how to implement this relatively basic feature.

The game works fine on mobile, but marking a square with a flag requires a tricky long-press on a tiny square that also triggers selector handles that are difficult to clear. So it’s not an ideal mobile interface.

Presentation

This was the only working version we tested that didn’t include sound effects. That’s fair, since the original Windows Minesweeper also didn’t include sound, but it’s still a notable relative omission since the prompt specifically asked for it.

The all-black “smiley face” button to start a game is a little off-putting, too, compared to the bright yellow version that’s familiar to both Minesweeper players and emoji users worldwide. And while that smiley face does start a new game when clicked, there’s also a superfluous “New Game” button taking up space for some reason.

“Fun” feature

The closest thing I found to a “fun” new feature here was the game adding a rainbow background pattern on the grid when I completed a game. While that does add a bit of whimsy to a successful game, I expected a little more.

Coding experience

Benj notes that he was pleasantly surprised by how well Mistral Vibe performed as an open-weight model despite lacking the big-money backing of the other contenders. It was relatively slow, however (third fastest out of four), and the result wasn’t great. Ultimately, its performance so far suggests that with more time and more training, a very capable AI coding agent may eventually emerge.

Overall rating: 4/10

This version got many of the basics right but left out chording and didn’t perform well on the small presentational and “fun” touches.

Agent 2: OpenAI Codex

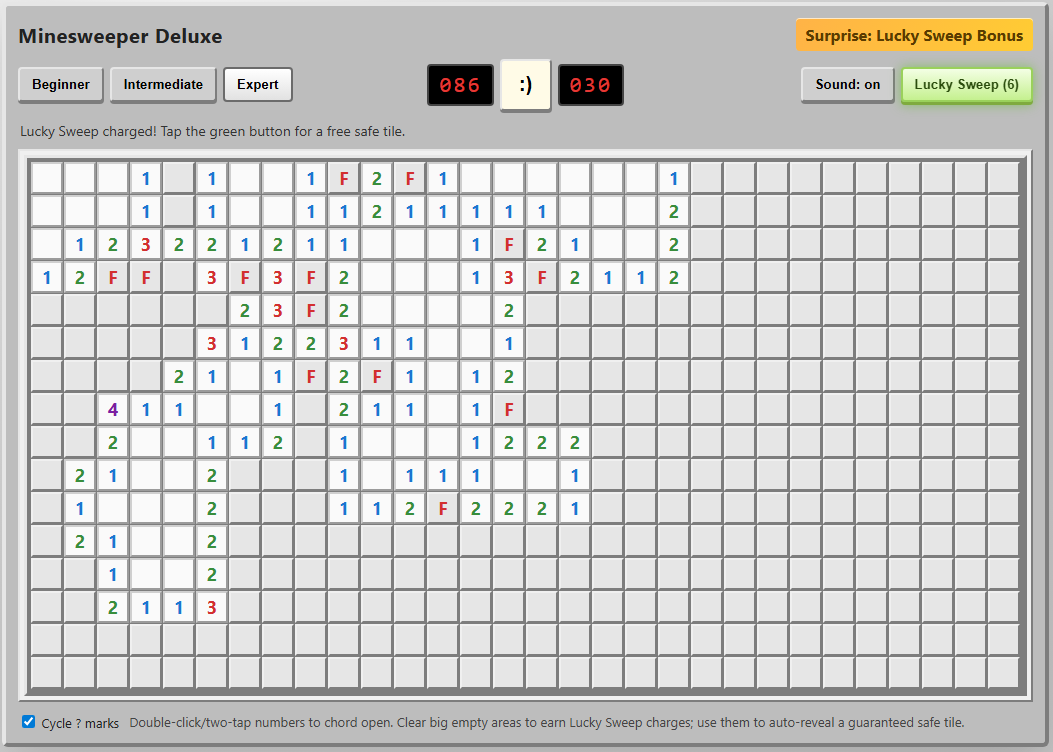

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate those chording instructions at the bottom. Credit: Benj Edwards

Implementation

Not only did this agent include the crucial “chording” feature, but it also included on-screen instructions for using it on both PC and mobile browsers. I was further impressed by the option to cycle through “?” marks when marking squares with flags, an esoteric feature I feel even most human Minesweeper cloners might miss.

On mobile, the option to hold your finger down on a square to mark a flag is a nice touch that makes this the most enjoyable handheld version we tested.

Presentation

The old-school emoticon smiley-face button is pretty endearing, especially when you blow up and get a red-tinted “X(“. I was less impressed by the playfield “graphics,” which use a simple “*” for revealed mines and an ugly red “F” for flagged tiles.

The beeps-and-boops sound effects reminded me of my first old-school, pre-Sound-Blaster PC from the late ’80s. That’s generally a good thing, but I still appreciated the game giving me the option to turn them off.

“Fun” feature

The “Surprise: Lucky Sweep Bonus” listed in the corner of the UI explains that clicking the button gives you a free safe tile when available. This can be pretty useful in situations where you’d otherwise be forced to guess between two tiles that are equally likely to be mines.

Overall, though, I found it a bit odd that the game gives you this bonus only after you find a large, cascading field of safe tiles with a single click. It mostly functions as a “win more” button rather than a feature that offers a good balance of risk versus reward.

Coding experience

OpenAI Codex has a nice terminal interface with features similar to Claude Code (local commands, permission management, and interesting animations showing progress), and it’s fairly pleasant to use (OpenAI also offers Codex through a web interface, but we did not use that for this evaluation). However, Codex took roughly twice as long to code a functional game than Claude Code did, which might contribute to the strong result here.

Overall: 9/10

The implementation of chording and cute presentation touches push this to the top of the list. We just wish the “fun” feature was a bit more fun.

Agent 3: Anthropic Claude Code

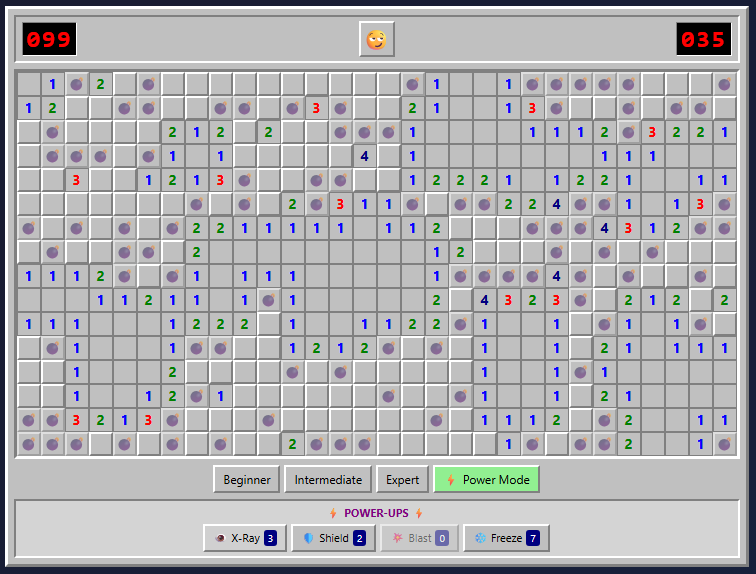

The Power Mod powers on display here make even Expert boards pretty trivial to complete. Credit: Benj Edwards

Implementation

Once again, we get a version that gets all the gameplay basics right but is missing the crucial chording feature that makes truly efficient Minesweeper play possible. This is like playing Super Mario Bros. without the run button or Ocarina of Time without Z-targeting. In a word: unacceptable.

The “flag mode” toggle on the mobile version of this game is perfectly functional, but it’s a little clunky to use. It also visually cuts off a portion of the board at the larger game sizes.

Presentation

Presentation-wise, this is probably the most polished version we tested. From the use of cute emojis for the “face” button to nice-looking bomb and flag graphics and simple but effective sound effects, this looks more professional than the other versions we tested.

That said, there are some weird presentation issues. The “beginner” grid has weird gaps between columns, for instance. The borders of each square and the flag graphics can also become oddly grayed out at points, especially when using Power Mode (see below).

“Fun” feature

The prominent “Power Mode” button in the lower-right corner offers some pretty fun power-ups that alter the core Minesweeper formula in interesting ways. But the actual powers are a bit hit-and-miss.

I especially liked the “Shield” power, which protects you from an errant guess, and the “Blast” power, which seems to guarantee a large cascade of revealed tiles wherever you click. But the “X-Ray” power, which reveals every bomb for a few seconds, could be easily exploited by a quick player (or a crafty screenshot). And the “Freeze” power is rather boring, just stopping the clock for a few seconds and amounting to a bit of extra time.

Overall, the game hands out these new powers like candy, which makes even an Expert-level board relatively trivial with Power Mode active. Simply choosing “Power Mode” also seems to mark a few safe squares right after you start a game, making things even easier. So while these powers can be “fun,” they also don’t feel especially well-balanced.

Coding experience

Of the four tested models, Claude Code with Opus 4.5 featured the most pleasant terminal interface experience and the fastest overall coding experience (Claude Code can also use Sonnet 4.5, which is even faster, but the results aren’t quite as full-featured in our experience). While we didn’t precisely time each model, Opus 4.5 produced a working Minesweeper in under five minutes. Codex took at least twice as long, if not longer, while Mistral took roughly three or four times as long as Claude Code. Gemini, meanwhile, took hours of tinkering to get two non-working results.

Overall: 7/10

The lack of chording is a big omission, but the strong presentation and Power Mode options give this effort a passable final score.

Agent 4: Google Gemini CLI

So… where’s the game? Credit: Benj Edwards

Implementation, presentation, etc.

Gemini CLI did give us a few gray boxes you can click, but the playfields are missing. While interactive troubleshooting with the agent may have fixed the issue, as a “one-shot” test, the model completely failed.

Coding experience

Of the four coding agents we tested, Gemini CLI gave Benj the most trouble. After developing a plan, it was very, very slow at generating any usable code (about an hour per attempt). The model seemed to get hung up attempting to manually create WAV file sound effects and insisted on requiring React external libraries and a few other overcomplicated dependencies. The result simply did not work.

Benj actually bent the rules and gave Gemini a second chance, specifying that the game should use HTML5. When the model started writing code again, it also got hung up trying to make sound effects. Benj suggested using the WebAudio framework (which the other AI coding agents seemed to be able to use), but the result didn’t work, which you can see at the link above.

Unlike the other models tested, Gemini CLI apparently uses a hybrid system of three different LLMs for different tasks (Gemini 2.5 Flash Lite, 2.5 Flash, and 2.5 Pro were available at the level of the Google account Benj paid for). When you’ve completed your coding session and quit the CLI interface, it gives you a readout of which model did what.

In this case, it didn’t matter because the results didn’t work. But it’s worth noting that Gemini 3 coding models are available for other subscription plans that were not tested here. For that reason, this portion of the test could be considered “incomplete” for Google CLI.

Overall: 0/10 (Incomplete)

Final verdict

OpenAI Codex wins this one on points, in no small part because it was the only model to include chording as a gameplay option. But Claude Code also distinguished itself with strong presentational flourishes and quick generation time. Mistral Vibe was a significant step down, and Google CLI based on Gemini 2.5 was a complete failure on our one-shot test.

While experienced coders can definitely get better results via an interactive, back-and-forth code editing conversation with an agent, these results show how capable some of these models can be, even with a very short prompt on a relatively straightforward task. Still, we feel that our overall experience with coding agents on other projects (more on that in a future article) generally reinforces the idea that they currently function best as interactive tools that augment human skill rather than replace it.

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.

We asked four AI coding agents to rebuild Minesweeper—the results were explosive Read More »