New OpenAI tool renews fears that “AI slop” will overwhelm scientific research

New “Prism” workspace launches just as studies show AI-assisted papers are flooding journals with diminished quality.

On Tuesday, OpenAI released a free AI-powered workspace for scientists. It’s called Prism, and it has drawn immediate skepticism from researchers who fear the tool will accelerate the already overwhelming flood of low-quality papers into scientific journals. The launch coincides with growing alarm among publishers about what many are calling “AI slop” in academic publishing.

To be clear, Prism is a writing and formatting tool, not a system for conducting research itself, though OpenAI’s broader pitch blurs that line.

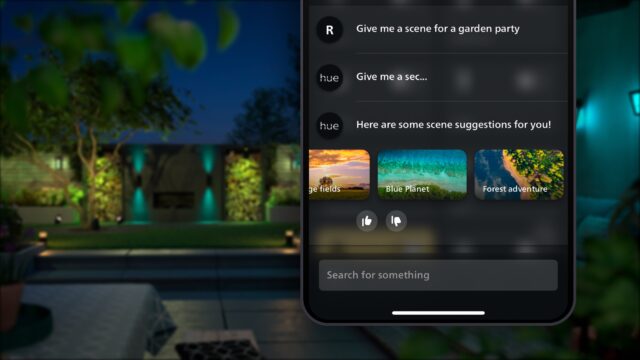

Prism integrates OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 model into a LaTeX-based text editor (a standard used for typesetting documents), allowing researchers to draft papers, generate citations, create diagrams from whiteboard sketches, and collaborate with co-authors in real time. The tool is free for anyone with a ChatGPT account.

“I think 2026 will be for AI and science what 2025 was for AI in software engineering,” Kevin Weil, vice president of OpenAI for Science, told reporters at a press briefing attended by MIT Technology Review. He said that ChatGPT receives about 8.4 million messages per week on “hard science” topics, which he described as evidence that AI is transitioning from curiosity to core workflow for scientists.

OpenAI built Prism on technology from Crixet, a cloud-based LaTeX platform the company acquired in late 2025. The company envisions Prism helping researchers spend less time on tedious formatting tasks and more time on actual science. During a demonstration, an OpenAI employee showed how the software could automatically find and incorporate relevant scientific literature, then format the bibliography.

But AI models are tools, and any tool can be misused. The risk here is specific: By making it easy to produce polished, professional-looking manuscripts, tools like Prism could flood the peer review system with papers that don’t meaningfully advance their fields. The barrier to producing science-flavored text is dropping, but the capacity to evaluate that research has not kept pace.

When asked about the possibility of the AI model confabulating fake citations, Weil acknowledged in the press demo that “none of this absolves the scientist of the responsibility to verify that their references are correct.”

Unlike traditional reference management software (such as EndNote), which has formatted citations for over 30 years without inventing them, AI models can generate plausible-sounding sources that don’t exist. Weil added: “We’re conscious that as AI becomes more capable, there are concerns around volume, quality, and trust in the scientific community.”

The slop problem

Those concerns are not hypothetical, as we have previously covered. A December 2025 study published in the journal Science found that researchers using large language models to write papers increased their output by 30 to 50 percent, depending on the field. But those AI-assisted papers performed worse in peer review. Papers with complex language written without AI assistance were most likely to be accepted by journals, while papers with complex language likely written by AI models were less likely to be accepted. Reviewers apparently recognized that sophisticated prose was masking weak science.

“It is a very widespread pattern across different fields of science,” Yian Yin, an information science professor at Cornell University and one of the study’s authors, told the Cornell Chronicle. “There’s a big shift in our current ecosystem that warrants a very serious look, especially for those who make decisions about what science we should support and fund.”

Another analysis of 41 million papers published between 1980 and 2025 found that while AI-using scientists receive more citations and publish more papers, the collective scope of scientific exploration appears to be narrowing. Lisa Messeri, a sociocultural anthropologist at Yale University, told Science magazine that these findings should set off “loud alarm bells” for the research community.

“Science is nothing but a collective endeavor,” she said. “There needs to be some deep reckoning with what we do with a tool that benefits individuals but destroys science.”

Concerns about AI-generated scientific content are not new. In 2022, Meta pulled a demo of Galactica, a large language model designed to write scientific literature, after users discovered it could generate convincing nonsense on any topic, including a wiki entry about a fictional research paper called “The benefits of eating crushed glass.” Two years later, Tokyo-based Sakana AI announced “The AI Scientist,” an autonomous research system that critics on Hacker News dismissed as producing “garbage” papers. “As an editor of a journal, I would likely desk-reject them,” one commenter wrote at the time. “They contain very limited novel knowledge.”

The problem has only grown worse since then. In his first editorial of 2026 for Science, Editor-in-Chief H. Holden Thorp wrote that the journal is “less susceptible” to AI slop because of its size and human editorial investment, but he warned that “no system, human or artificial, can catch everything.” Science currently allows limited AI use for editing and gathering references but requires disclosure for anything beyond that and prohibits AI-generated figures.

Mandy Hill, managing director of academic publishing at Cambridge University Press & Assessment, has been even more blunt. In October 2025, she told Retraction Watch that the publishing ecosystem is under strain and called for “radical change.” She explained to the University of Cambridge publication Varsity that “too many journal articles are being published, and this is causing huge strain” and warned that AI “will exacerbate” the problem.

Accelerating science or overwhelming peer review?

OpenAI is serious about leaning on its ability to accelerate science, and the company laid out its case for AI-assisted research in a report published earlier this week. It profiles researchers who say AI models have sped up their work, including a mathematician who used GPT-5.2 to solve an open problem in optimization over three evenings and a physicist who watched the model reproduce symmetry calculations that had taken him months to derive.

Those examples go beyond writing assistance into using AI for actual research work, a distinction OpenAI’s marketing intentionally blurs. For scientists who don’t speak English fluently, AI writing tools could legitimately accelerate the publication of good research. But that benefit may be offset by a flood of mediocre submissions jamming up an already strained peer-review system.

Weil told MIT Technology Review that his goal is not to produce a single AI-generated discovery but rather “10,000 advances in science that maybe wouldn’t have happened or wouldn’t have happened as quickly.” He described this as “an incremental, compounding acceleration.”

Whether that acceleration produces more scientific knowledge or simply more scientific papers remains to be seen. Nikita Zhivotovskiy, a statistician at UC Berkeley not connected to OpenAI, told MIT Technology Review that GPT-5 has already become valuable in his own work for polishing text and catching mathematical typos, making “interaction with the scientific literature smoother.”

But by making papers look polished and professional regardless of their scientific merit, AI writing tools may help weak research clear the initial screening that editors and reviewers use to assess presentation quality. The risk is that conversational workflows obscure assumptions and blur accountability, and they might overwhelm the still very human peer review process required to vet it all.

OpenAI appears aware of this tension. Its public statements about Prism emphasize that the tool will not conduct research independently and that human scientists remain responsible for verification.

Still, one commenter on Hacker News captured the anxiety spreading through technical communities: “I’m scared that this type of thing is going to do to science journals what AI-generated bug reports is doing to bug bounties. We’re truly living in a post-scarcity society now, except that the thing we have an abundance of is garbage, and it’s drowning out everything of value.”

New OpenAI tool renews fears that “AI slop” will overwhelm scientific research Read More »