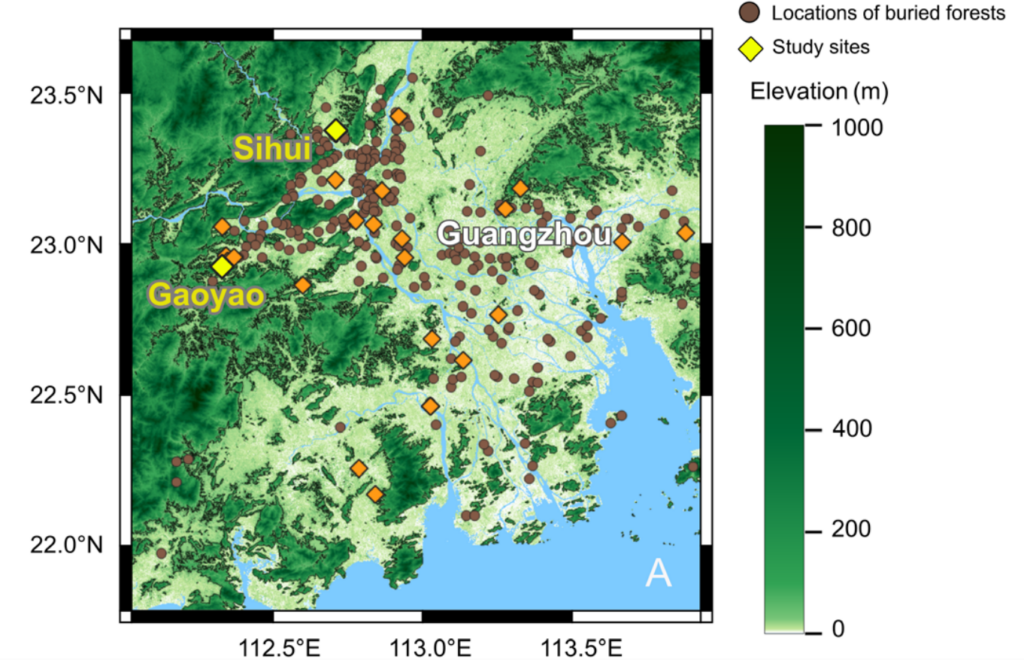

Oldest wooden tools in East Asia may have come from any of three species

That leaves a few possibilities: Denisovans, Homo heidelbergensis (the common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and our species), or Homo erectus. All three species could have lived in the area at the time. But nobody at Gantangqing left behind any convenient, readily identifiable bones along with their wooden tools, stone tools, and butchered animal bones (so inconsiderate of them), making it hard to pin down exactly which species these 300,000-year-old hunter-gatherers belonged to.

Homo erectus had been in Asia for more than a million years by the time Gantangqing’s lakeshore was occupied; the oldest Homo erectus fossils in Asia are from Indonesia and date back 1.8 million years. They also stuck around until quite recently. In caves at a site called Zhoukoudian, outside Beijing in eastern China, Homo erectus remains date to sometime between 700,000 and 200,000 years ago (there’s still a lot of debate on exactly how old the site is).

All of that means that Homo erectus’ presence in the region overlaps the age of the wood tools at Gantangqing. And the stone tools found nearby are fairly simple cores and flakes that don’t rule out Homo erectus as their makers. Archaeologists haven’t unearthed evidence of Homo erectus making or using sophisticated wooden tools like this, but for a species that managed to harness fire and cross miles of ocean, it’s not too wild a speculation.

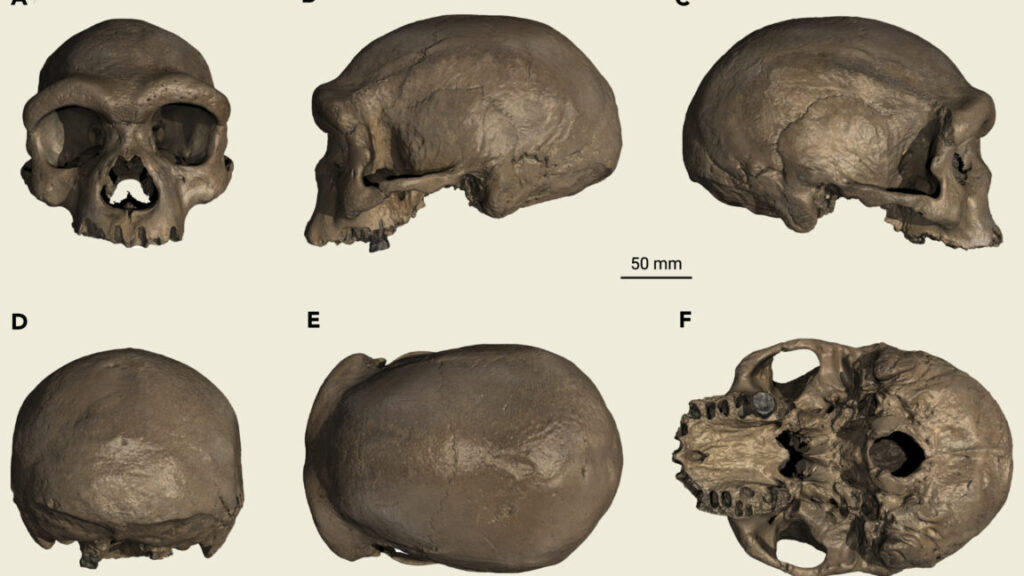

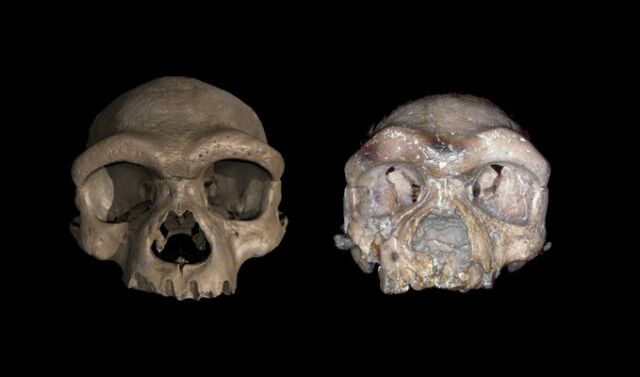

On the other hand, we know that Denisovans were probably in the area, too, or at least not too far away. A recently identified Denisovan skull from Harbin, China, is 146,000 years old but bears a striking resemblance to other hominin skulls from sites all over China, which range from 300,000 to 200,000 years old. And making finely crafted wooden tools fits with everything we know about Denisovan capabilities.

Then there’s Homo heidelbergensis, the direct ancestor of Denisovans. In fact, it’s a little hard to tell where hominins stop being Homo heidelbergensis and start being Denisovans, or even whether the distinction matters. It’s a problem paleoanthropologists refer to as the “muddle in the Middle,” since both species date to the Middle Pleistocene. So if Homo erectus and Denisovans are in the running, so is Homo heidelbergensis, by default.

And unless someone finds a telltale skull nearby or another very similar toolkit at a site with telltale skulls to consult, we may not know for sure.

Science, 2023. DOI: 10.1126/science.adr8540 (About DOIs).

Oldest wooden tools in East Asia may have come from any of three species Read More »