How Easter Island’s giant statues “walked” to their final platforms

Workers with ropes could make the moai “walk” in zig-zag motion along roads tailor-made for the purpose.

Easter Island is famous for its giant monumental statues, called moai, built some 800 years ago and typically mounted on platforms called ahu. Scholars have puzzled over the moai on Easter Island for decades, pondering their cultural significance, as well as how a Stone Age culture managed to carve and transport statues weighing as much as 92 tons. One hypothesis, championed by archaeologist Carl Lipo of Binghamton University, among others, is that the statues were transported in a vertical position, with workers using ropes to essentially “walk” the moai onto their platforms.

The oral traditions of the people of Rapa Nui certainly include references to the moai “walking” from the quarry to their platforms, such as a song that tells of an early ancestor who made the statues walk. While there have been rudimentary field tests showing it might have been possible, the hypothesis has also generated a fair amount of criticism. So Lipo has co-authored a new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science offering fresh experimental evidence of “walking” moai, based on 3D modeling of the physics and new field tests to recreate that motion.

The first Europeans arrived in the 17th century and found only a few thousand inhabitants on the tiny island (just 14 by 7 miles across) thousands of miles away from any other land. In order to explain the presence of so many moai, the assumption has been that the island was once home to tens of thousands of people. But Lipo thought perhaps the feat could be accomplished with fewer workers. In 2012, Lipo and his colleague, Terry Hunt of the University of Arizona, showed that you could transport a 10-foot, 5-ton moai a few hundred yards with just 18 people and three strong ropes by employing a rocking motion.

In 2018, Lipo followed up with an intriguing hypothesis for how the islanders placed red hats on top of some moai; those can weigh up to 13 tons. He suggested the inhabitants used ropes to roll the hats up a ramp. Lipo and his team later concluded (based on quantitative spatial modeling) that the islanders likely chose the statues’ locations based on the availability of fresh water sources, per a 2019 paper in PLOS One.

The 2012 experiment demonstrated proof of principle, so why is Lipo revisiting it now? “I always felt that the [original] experiment was disconnected to some degree of theory—that we didn’t have particular expectations about numbers of people, rate of transport, road slope that could be walked, and so on,” Lipo told Ars. There were also time constraints because the attempt was being filmed for a NOVA documentary.

“That experiment was basically a test to see if we could make it happen or not,” he explained. “Fortunately, we did, and our joy in doing so is pretty well represented by our hoots and hollers when it started to walk with such limited efforts. Some of the limitation of the work was driven by the nature of TV. [The film crew] just wanted us—in just a day and half—to give it a shot. It was 4: 30 on the last day when it finally worked so we really didn’t get a lot of time to explore variability. We also didn’t have any particular predictions to test.”

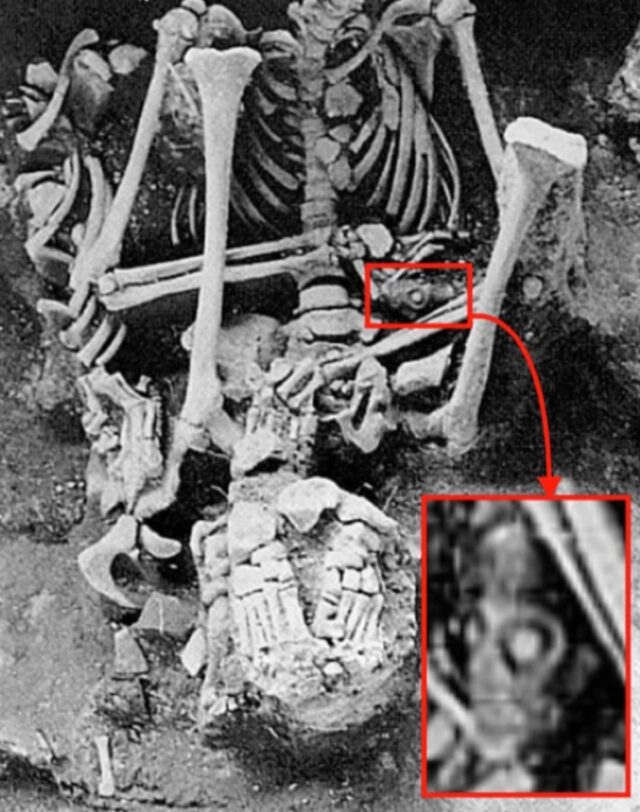

Example of a road moai that fell and was abandoned after an attempt to re-erect it by excavating under its base, leaving it partially buried at an angle. Credit: Carl Lipo

This time around, “We wanted to explore a bit of the physics: to show that what we did was pretty easily predicted by the physical properties of the moai—its shape, size, height, number of people on ropes, etc.—and that our success in terms of team size and rate of walking was consistent with predictions,” said Lipo. “This enables us to address one of the central critiques that always comes up: ‘Well, you did this with a 5-ton version that was 10 feet tall, but it would never work with a 30-ft-tall version that weighs 30 tons or more.'”

All about that base

You can have ahu (platforms) without moai (statues) and moai without ahu, usually along the roads leading to ahu; they were likely being transported and never got to their destination. Lipo and Hunt have amassed a database of 962 moai across the island, compiled through field surveys and photogrammetric documentation. They were particularly interested in 62 statues located along ancient transport roads that seemed to have been abandoned where they fell.

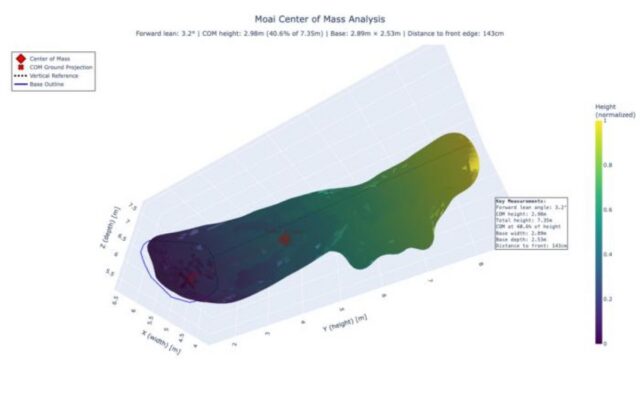

Their analysis revealed that these road moai had significantly wider bases relative to shoulder width, compared to statues mounted on platforms. This creates a stable foundation that lowers the center of mass so that the statue is more conducive to the side-to-side motion of walking transport without toppling over. Platform statues, by contrast, have shoulders wider than the base for a more top-heavy configuration.

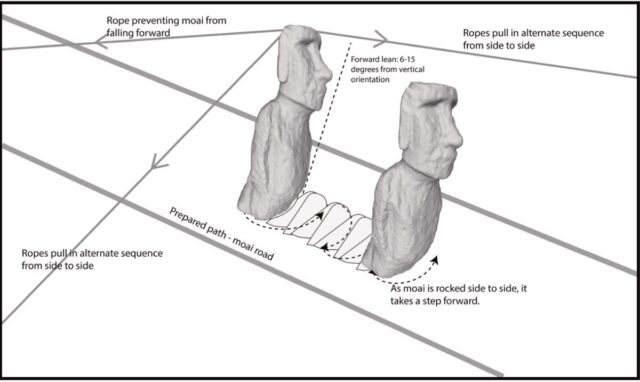

The road moai also have a consistent and pronounced forward lean of between 6 degrees to 15 degrees from the vertical position, which moves the center of mass close to or just beyond the base’s front edge. Lipo and Hunt think this was due to careful engineering, not coincidence. It’s not conducive to stable vertical display but it is a boon during walking transport, because the forward lean causes the statue to fall forward when tilted laterally, with the rounded front base edge serving as a crucial pivot point. So every lateral rocking motion results in a forward “step.”

Per the authors, there is strong archaeological evidence that carvers modified the statues once they arrived at their platform destinations, modifying the base to eliminate the lean by removing material from the front. This shifted the center of mass over the base area for a stable upright position. The road moai even lack the carved eye sockets designed to hold white coral eyes with obsidian or red scoria for pupils—a final post-transport step once the statues had been mounted on their platforms.

Based on 3D modeling, Lipo and his team created a precisely scaled replica of one of the road moai, weighing 4.35 metric tons with the same proportions and mass distribution of the original statue. “Of course, we’d love to build a 30-foot-tall version, but the physical impossibility of doing so makes it a challenging task, nor is it entirely necessary,” said Lipo. “Through physics, we can now predict how many people it would take and how it would be done. That is key.”

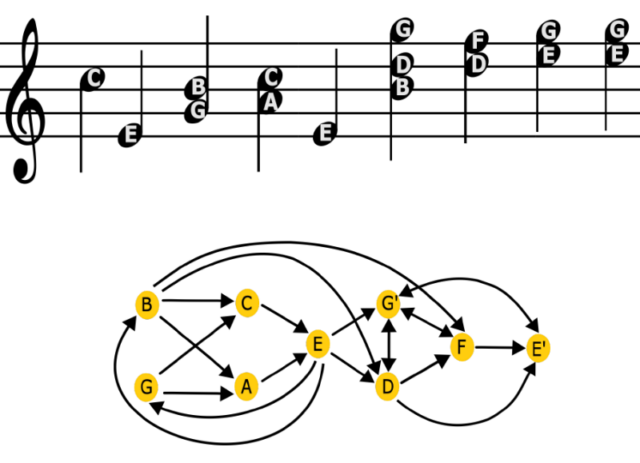

Lipo’s team created 3D models of moai to determine the unique characteristics that made them able to be “walked” across Rapa Nui. Credit: Carl Lipo

The new field trials required 18 people, four on each lateral rope and 10 on a rear rope, to achieve the side-to-side walking motion, and they were efficient enough in coordinating their efforts to move the statue forward 100 meters in just 40 minutes. That’s because the method operates on basic pendulum dynamics, per the authors, which minimizes friction between the base and the ground. It’s also a technique that exploits the gradual build-up of amplitude, which “suggests a sophisticated understanding of resonance principles,” Lipo and Hunt wrote.

So the actual statues could have been moved several kilometers over the course of weeks with only modest-sized crews of between 20-50 people, i.e., roughly the size of an extended family or “small lineage group” on Easter Island. Once the crew gets the statue rocking side to side—which can require between 15 to 60 people, depending on the size and weight of the moai—the resulting oscillation only needs minimal energy input from a smaller team of rope handlers to maintain that motion. They mostly provide guidance.

Lipo was not the first to test the walking hypothesis. Earlier work includes that of Czech experimental archaeologist Pavel Pavel, who conducted similar practical experiments on Easter Island in the 1980s after being inspired by Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki. (Heyerdahl even participated in the experiments.) Pavel’s team was able to demonstrate a kind of “shuffling” motion, and he concluded that just 16 men and one leader were sufficient to transport the statues.

Per Lipo and Hunt, Pavel’s demonstration didn’t result in broad acceptance of the walking hypothesis because it still required a huge amount of effort to tilt the statue, producing more of a twisting motion rather than efficient forward movement. This would only have moved a large statue 100 meters a day under ideal conditions. The base was also likely to be damaged from friction with the ground. Lipo and Hunt maintain this is because Pavel (and others who later tried to reproduce his efforts) used the wrong form of moai for those earlier field tests: those erected on the platforms, already modified for vertical stability and permanent display, and not the road moai with shapes more conducive to vertical transport.

“Pavel deserves recognition for taking oral traditions seriously and challenging the dominant assumption of horizontal transport, a move that invited ridicule from established scholars,” Lipo and Hunt wrote. “His experiments suggested that vertical transport was feasible and consistent with cultural memory. Our contribution builds on this by showing that ancestral engineers intentionally designed statues for walking. Those statues were later modified to stand erect on ceremonial platforms, a transformation that effectively erased the morphological features essential for movement.”

The evidence of the roadways

Lipo and Hunt also analyzed the roadways, noting that these ancient roadbeds had concave cross sections that would have been problematic for moving the statues horizontally using wooden rollers or frames perpendicular to those roads. But that concave shape would help constrain rocking movement during vertical transport. And the moai roads were remarkably level with slopes of, on average, 2–3 percent. For the occasional steeper slopes, such as walking a moai up a ramp to the top of an ahu, Lipo and Hunt’s field experiments showed that these could be navigated successfully through controlled stepping.

Furthermore, the distribution pattern of the roadways is consistent with the road moai being left due to mechanical failure. “Arguments that the moai were placed ceremonially in preparation for quarrying have become more common,” said Lipo. “The algorithm there is to claim that positions are ritual, without presenting anything that is falsifiable. There is no reason why the places the statues fell due to mechanical reasons couldn’t later become ‘ritual,’ in the same way that everything on the island could be claimed to be ritual—a circular argument. But to argue that they were placed there purposefully for ritual purposes demands framing the explanation in a way that is falsifiable.”

Schematic representation of the moai transport method using coordinated rope pulling to achieve a “walking” motion. Credit: Carl Lipo and Terry Hunt, 2025

“The only line of evidence that is presented in this way is the presence of ‘platforms’ that were found beneath the base of one moai, which is indeed intriguing,” Lipo continued. “However, those platforms can be explained in other ways, given that the moai certainly weren’t moved from the quarry to the ahu in one single event. They were paused along the way, as is clear from the fact that the roads appear to have been constructed in segments with different features. Their construction appears to be part of the overall transport process.”

Lipo’s work has received a fair share of criticism from other scholars over the years, and his and Hunt’s paper includes a substantial section rebutting the most common of those critiques. “Archaeologists tend to reject (in practice) the idea that the discipline can construct cumulative knowledge,” said Lipo. “In the case of moai transport, we’ve strived to assemble as much empirical evidence as possible and have forwarded an explanation that best accounts for what we can observe. Challenges to these ideas, however, do not come from additional studies with new data but rather just new assertions.”

“This leads the public to believe that we (as a discipline) can never really figure anything out and are always going to be a speculative enterprise, spinning yarns and arguing with each other,” Lipo continued. “With the erosion of trust in science, this is fairly catastrophic to archaeology as a whole but also the whole scientific enterprise. Summarizing the results in the way we do here is an attempt to point out that we can build falsifiable accounts and can make contributions to cumulative knowledge that have empirical consequences—even with something as remarkable as the transport of moai.”

Experimental archaeology is a relatively new field that some believe could be the future of archaeology. “I think experimental archaeology has potential when it’s tied to physics and chemistry,” said Lipo. “It’s not just recreating something and then arguing it was done in the same way in the past. Physics and chemistry are our time machines, allowing us to explain why things are the way they are in the present in terms of the events that occurred in the past. The more we can link the theory needed to explain the present, the better we can explain the past.”

DOI: Journal of Archaeological Science, 2025. 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106383 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

How Easter Island’s giant statues “walked” to their final platforms Read More »