When software updates actually improve—instead of ruin—our favorite devices

Opinion: These tech products have gotten better over time.

The Hatch Restore 2 smart alarm clock. Credit: Scharon Harding

For many, there’s a feeling of dread associated with software updates to your favorite gadget. Updates to a beloved gadget can frequently result in outrage, from obligatory complaints around bugs to selective aversions to change from Luddites and tech enthusiasts.

In addition to those frustrations, there are times when gadget makers use software updates to manipulate product functionality and seriously upend owners’ abilities to use their property as expected. We’ve all seen software updates render gadgets absolutely horrible: Printers have nearly become a four-letter word as the industry infamously issues updates that brick third-party ink and scanning capabilities. We’ve also seen companies update products that caused features to be behind a paywall or removed entirely. This type of behavior has contributed to some users feeling wary of software updates in fear of them diminishing the value of already-purchased hardware.

On the other hand, there are times when software updates enrich the capabilities of smart gadgets. These updates are the types of things that can help devices retain or improve their value, last longer, and become less likely to turn into e-waste.

For example, I’ve been using the Hatch Restore 2 sunrise alarm clock since July. In that time, updates to its companion app have enabled me to extract significantly more value from the clock and explore its large library of sounds, lights, and customization options.

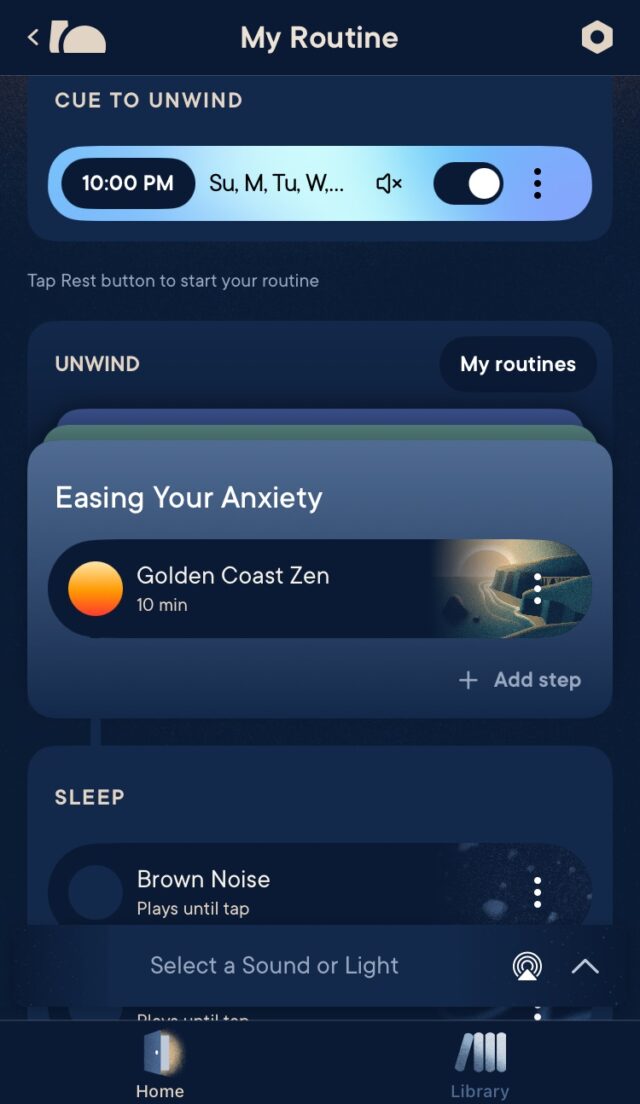

The Hatch Sleep iOS app used to have tabs on the bottom for Rest, for setting how the clock looks and sounds when you’re sleeping; Library, for accessing the clock’s library of sounds and colors; and Rise, for setting how the clock looks and sounds when you’re waking up. Today, the bottom of the app just has Library and Home tabs, with Home featuring all the settings for Rest and Rise, as well as for Cue (the clock’s settings for reminding you it’s time to unwind for the night) and Unwind (sounds and settings that the clock uses during the time period leading up to sleep).

A screenshot of the Home section of the Hatch Sleep app.

Hatch’s app has generally become cleaner after hiding things like its notification section. Hatch also updated the app to store multiple Unwind settings you can swap around. Overall, these changes have made customizing my settings less tedious, which means I’ve been more inclined to try them. Before the updates, I mostly used the app to set my alarm and change my Rest settings. I often exited the app prematurely after getting overwhelmed by all the different tabs I had to toggle through (toggling through tabs was also more time-consuming).

Additionally, Hatch has updated the app since I started using it so that disabled alarms are placed under an expanding drawer. This has reduced the chances of me misreading the app and thinking I have an alarm set when it’s not currently enabled while providing a clearer view of which alarms actually are enabled.

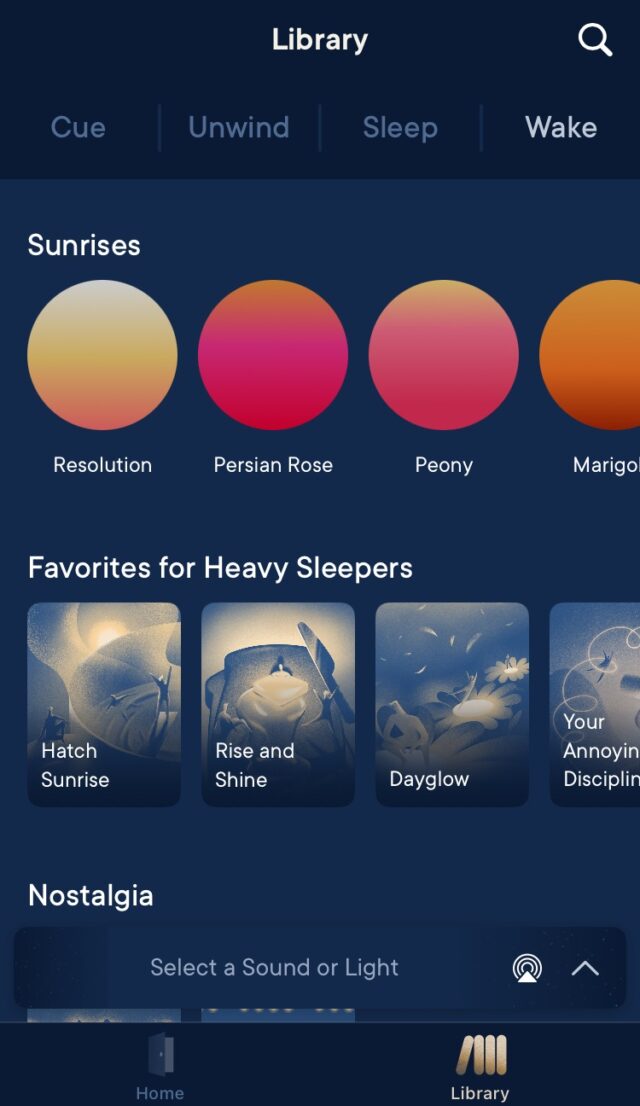

The Library tab was also recently updated to group lights and sounds under Cue, Unwind, Sleep, and Wake, making it easier to find the type of setting I’m interested in.

The app also started providing more helpful recommendations, such as “favorites for heavy sleepers.”

Better over time

Software updates have made it easier for me to enjoy the Restore 2 hardware. Honestly, I don’t know if I’d still use the clock without these app improvements. What was primarily a noise machine this summer has become a multi-purpose device with much more value.

Now, you might argue that Hatch could’ve implemented these features from the beginning. That may have been more sensible, but as a tech enthusiast, I still find something inherently cool about watching a gadget improve in ways that affect how I use the hardware and align with what I thought my gadget needed. I agree that some tech gadgets are released prematurely and overly rely on updates to earn their initial prices. But it’s also advantageous for devices to improve over time.

The Steam Deck is another good example. Early adopters might have been disappointed to see missing features like overclocking controls, per-game power profiles, or Windows drivers. Valve has since added those features.

Valve only had a few dozen Hardware department employees in the run up to the launch of the Steam Deck. Credit: Sam Machkovech

Valve has also added more control over the Steam Deck since its release, including the power to adjust resolution and refresh rates for connected external displays. It’s also upped performance via an October update that Valve claimed could improve the battery life of LCD models by up to 10 percent in “light load situations.”

These are the kinds of updates that still allowed the Steam Deck to be playable for months, but the features were exciting additions once they arrived. When companies issue updates reliably and in ways that improve the user experience, people are less averse to updating their gadgets, which could also be critical for device functionality and security.

Adding new features via software updates can make devices more valuable to owners. Updates that address accessibility needs go even further by opening up the gadgets to more people.

Apple, for example, demonstrated the power that software updates can have on accessibility by adding a hearing aid feature to the AirPods Pro 2 in October, about two years after the earbuds came out. Similarly, Amazon updated some Fire TV models in December to support simultaneous audio broadcasting from internal speakers and hearing aids. It also expanded the number of hearing aids supported by some Fire TV models as well as its Fire TV Cube streaming device.

For some, these updates had a dramatic impact on how they could use the devices, demonstrating a focus on user, rather than corporate, needs.

Update upswings

We all know that corporations sometimes leverage software updates to manipulate products in ways that prioritize internal or partner needs over those of users. Unfortunately, this seems like something we have to get used to, as an increasing number of devices join the Internet of Things and rely on software updates.

Innovations also mean that some companies are among the first to try to make sustainable business models for their products. Sometimes our favorite gadgets are made by young companies or startups with unstable funding that are forced to adapt amid challenging economics or inadequate business strategy. Sometimes, the companies behind our favorite tech products are beholden to investors and pressure for growth. These can lead to projects being abandoned or to software updates that look to squeeze more money out of customers.

As happy as I am to find my smart alarm clock increasingly easy to use, those same software updates could one day lock the features I’ve grown fond of behind a paywall (Hatch already has a subscription option available). Having my alarm clock lose functionality overnight without physical damage isn’t the type of thing I’d have to worry about with a dumb alarm clock, of course.

But that’s the gamble that tech fans take, which makes those privy to the problematic tactics used by smart device manufacturers stay clear from certain products.

Still, when updates provide noticeable, meaningful changes to how people can use their devices, technology feels futuristic, groundbreaking, and exciting. With many companies using updates for their own gain, it’s nice to see some firms take the opportunity to give customers more.

When software updates actually improve—instead of ruin—our favorite devices Read More »