Research roundup: 7 cool science stories we almost missed

Other July stories: Solving a 150-year-old fossil mystery and the physics of tacking a sailboat.

150-year-old fossil of Palaeocampa anthrax isn’t a sea worm after all. Credit: Christian McCall

It’s a regrettable reality that there is never enough time to cover all the interesting scientific stories we come across each month. In the past, we’ve featured year-end roundups of cool science stories we (almost) missed. This year, we’re experimenting with a monthly collection. July’s list includes the discovery of the tomb of the first Maya king of Caracol in Belize, the fluid dynamics of tacking a sailboat, how to determine how fast blood was traveling when it stained cotton fabric, and how the structure of elephant ears could lead to more efficient indoor temperature control in future building designs, among other fun stories.

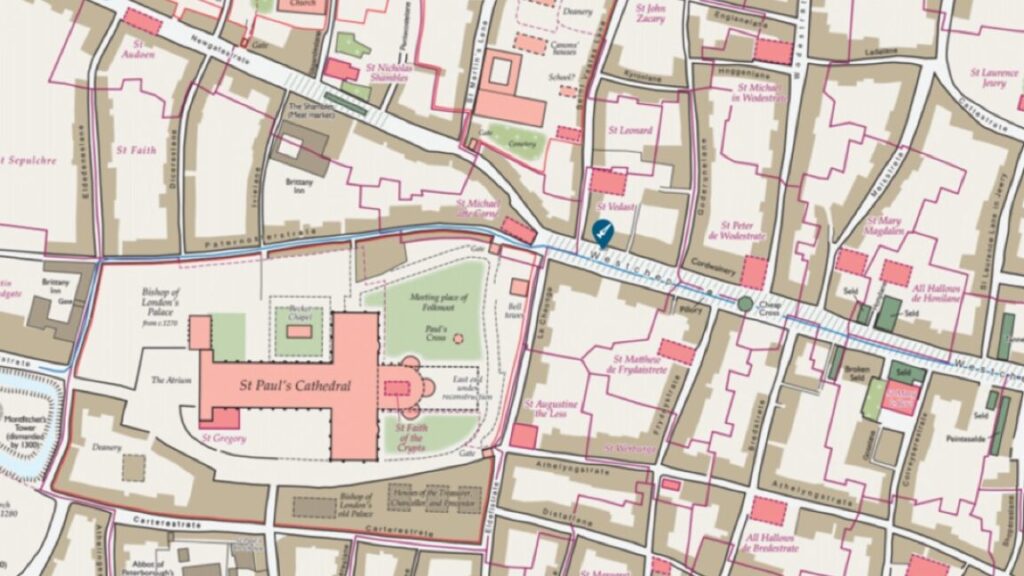

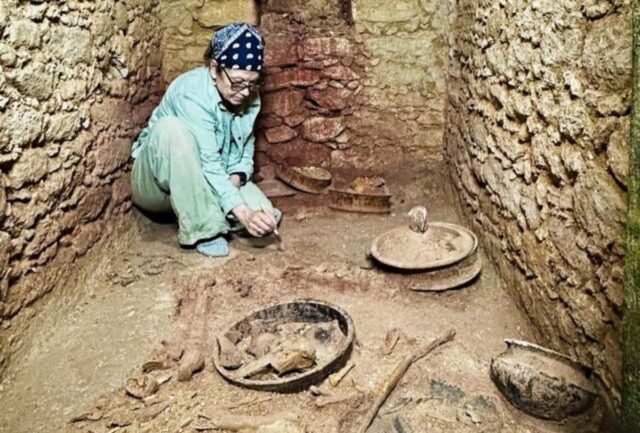

Tomb of first king of Caracol found

Credit: Caracol Archeological Project/University of Houston

Archaeologists Arlen and Diane Chase are the foremost experts on the ancient Maya city of Caracol in Belize and are helping to pioneer the use of airborne LiDAR to locate hidden structures in dense jungle, including a web of interconnected roadways and a cremation site in the center of the city’s Northeast Acropolis plaza. They have been painstakingly excavating the site since the mid-1980s. Their latest discovery is the tomb of Te K’ab Chaak, Caracol’s first ruler, who took the throne in 331 CE and founded a dynasty that lasted more than 460 years.

This is the first royal tomb the husband-and-wife team has found in their 40+ years of excavating the Caracol site. Te K’ab Chaak’s tomb (containing his skeleton) was found at the base of a royal family shrine, along with pottery vessels, carved bone artifacts, jadeite jewelry, and a mosaic jadeite death mask. The Chases estimate that the ruler likely stood about 5’7″ tall and was probably quite old when he died, given his lack of teeth. The Chases are in the process of reconstructing the death mask and conducting DNA and stable isotope analysis of the skeleton.

How blood splatters on clothing

Credit: Jimmy Brown/CC BY 2.0

Analyzing blood splatter patterns is a key focus in forensic science, and physicists have been offering their expertise for several years now, including in two 2019 studies on splatter patterns from gunshot wounds. The latest insights gleaned from physics concern the distinct ways in which blood stains cotton fabrics, according to a paper published in Forensic Science International.

Blood is a surprisingly complicated fluid, in part because the red blood cells in human blood can form long chains, giving it the consistency of sludge. And blood starts to coagulate immediately once it leaves the body. Blood is also viscoelastic: not only does it deform slowly when exposed to an external force, but once that force has been removed, it will return to its original configuration. Add in coagulation and the type of surface on which it lands, and correctly interpreting the resulting spatter patterns becomes incredibly difficult.

The co-authors of the July study splashed five different fabric surfaces with pig’s blood at varying velocities, capturing the action with high-speed cameras. They found that when a blood stain has “fingers” spreading out from the center, the more fingers there are, the faster the blood was traveling when it struck the fabric. And the faster the blood was moving, the more “satellite droplets” there will be—tiny stains surrounding the central stain. Finally, it’s much easier to estimate the velocity of blood splatter on plain-woven cotton than on other fabrics like twill. The researchers plan to extend future work to include a wider variety of fabrics, weaves, and yarns.

DOI: Forensic Science International, 2025. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2025.112543 (About DOIs).

Offshore asset practices of the uber-rich

The uber-rich aren’t like the rest of us in so many ways, including their canny exploitation of highly secretive offshore financial systems to conceal their assets and/or identities. Researchers at Dartmouth have used machine learning to analyze two public databases and identified distinct patterns in the strategies oligarchs and billionaires in 65 different countries employ when squirreling away offshore assets, according to a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

One database tracks offshore finance, while the other rates different countries on their “rule of law.” This enabled the team to study key metrics like how much of their assets elites move offshore, how much they diversify, and how much they make use of “blacklisted” offshore centers that are not part of the mainstream financial system. The researchers found three distinct patterns, all tied to where an oligarch comes from.

Billionaires from authoritarian countries are more likely to diversify their hidden assets across many different centers—a “confetti strategy”—perhaps because these are countries likely to exact political retribution. Others, from countries with effective government regulations—or where there is a pronounced lack of civil rights—are more likely to employ a “concealment strategy” that includes more blacklisted jurisdictions, relying more on bearer shares that protect their anonymity. Those elites most concerned about corruption and/or having their assets seized typically employ a hybrid strategy.

The work builds on an earlier 2023 study concluding that issuing sanctions on individual oligarchs in Russia, China, the US, and Hong Kong is less effective than targeting the small, secretive network of financial experts who manage that wealth on behalf of the oligarchs. That’s because sanctioning just one wealth manager effectively takes out several oligarchs at once, per the authors.

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0326228 (About DOIs).

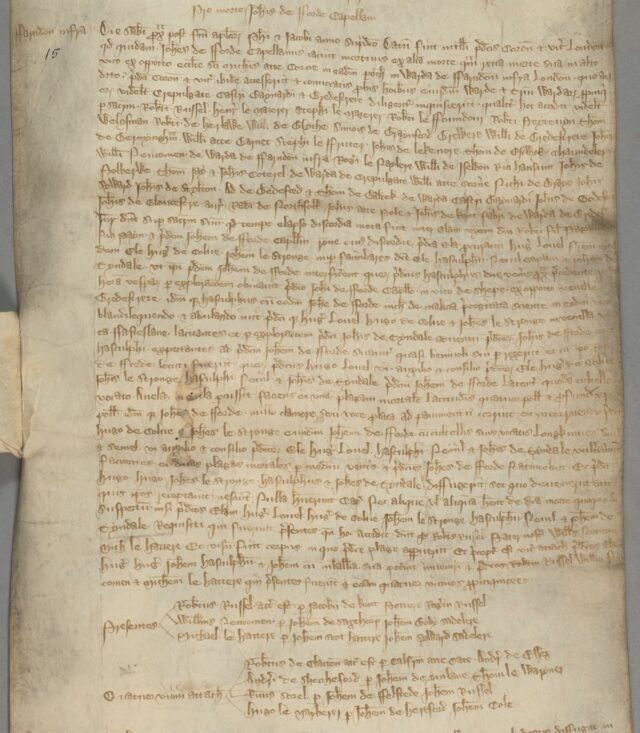

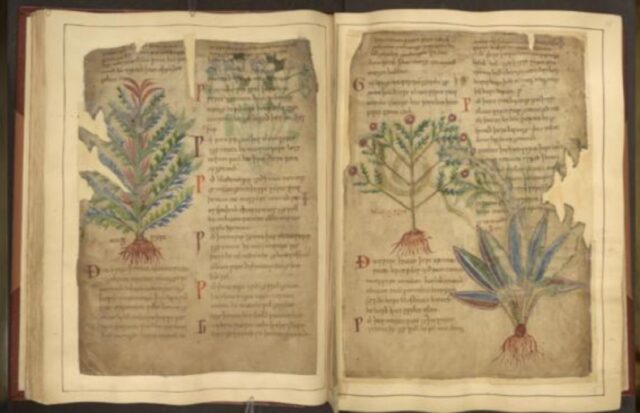

Medieval remedies similar to TikTok trends

Credit: The British Library

The Middle Ages are stereotypically described as the “Dark Ages,” with a culture driven by superstition—including its medical practices. But a perusal of the hundreds of medical manuscripts collected in the online Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine (CEMLM) reveals that in many respects, medical practices were much more sophisticated; some of the remedies are not much different from alternative medicine remedies touted by TikTok influencers today. That certainly doesn’t make them medically sound, but it does suggest we should perhaps not be too hasty in who we choose to call backward and superstitious.

Per Binghamton University historian Meg Leja, medievalists were not “anti-science.” In fact, they were often quite keen on learning from the natural world. And their health practices, however dubious they might appear to us—lizard shampoo, anyone?—were largely based on the best knowledge available at the time. There are detox cleanses and topical ointments, such as crushing the stone of a peach, mixing it with rose oil, and smearing it on one’s forehead to relieve migraine pain. (Rose oil may actually be an effective migraine pain reliever.) The collection is well worth perusing; pair it with the Wellcome-funded Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries to learn even more about medieval medical recipes.

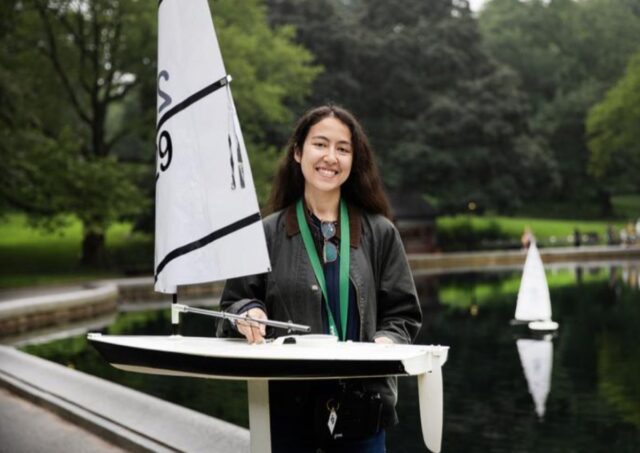

Physics of tacking a sailboat

Credit: Jonathan King/NYU

Possibly the most challenging basic move for beginner sailors is learning how to tack to sail upwind. Done correctly, the sail will flip around into a mirror image of its previous shape. And in competitive sailboat racing, a bad tack can lose the race. So physicists at the University of Michigan decided to investigate the complex fluid dynamics at play to shed more light on the tricky maneuver, according to a paper published in the journal Physical Review Fluids.

After modeling the maneuver and conducting numerical simulations, the physicists concluded that there are three primary factors that determine a successful tack: the stiffness of the sail, its tension before the wind hits, and the final sail angle in relation to the direction of the wind. Ideally, one wants a less flexible, less curved sail with high tension prior to hitting the wind and to end up with a 20-degree final sail angle. Other findings: It’s harder to flip a slack sail when tacking, and how fast one manages to flip the sail depends on the sail’s mass and the speed and acceleration of the turn.

DOI: Physical Review Fluids, 2025. 10.1103/37xg-vcff (About DOIs).

Elephant ears inspire building design

Maintaining a comfortable indoor temperature constitutes the largest fraction of energy usage for most buildings, with the surfaces of walls, windows, and ceilings contributing to roughly 63 percent of energy loss. Engineers at Drexel University have figured out how to make surfaces that help rather than hamper efforts to maintain indoor temperatures: using so-called phase-change materials that can absorb and release thermal energy as needed as they shift between liquid and solid states. They described the breakthrough in a paper published in the Journal of Building Engineering.

The Drexel group previously developed a self-warming concrete using a paraffin-based material, similar to the stuff used to make candles. The trick this time around, they found, was to create the equivalent of a vascular network within cement-based building materials. They used a printed polymer matrix to create a grid of channels in the surface of concrete and filled those channels with the same paraffin-based material. When temperatures drop, the material turns into a solid and releases heat energy; as temperatures rise, it shifts its phase to a liquid and absorbs heat energy.

The group tested several different configurations and found that the most effective combination of strength and thermal regulation was realized with a diamond-shaped grid, which boasted the most vasculature surface area. This configuration successfully slowed the cooling and heating of its surface to between 1 and 1.2 degrees Celsius per hour, while holding up against stretching and compression tests. The structure is similar to that of jackrabbit and elephant ears, which have extensive vascular networks to help regulate body temperature.

DOI: Journal of Building Engineering, 2025. 10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112878 (About DOIs).

ID-ing a century-old museum specimen

Credit: Richard J. Knecht

Natural history museums have lots of old specimens in storage, and revisiting those specimens can sometimes lead to new discoveries. That’s what happened to University of Michigan evolutionary biologist Richard J. Knecht as he was poring over a collection at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology while a grad student there. One of the fossils, originally discovered in 1865, was labeled a millipede. But Knecht immediately recognized it as a type of lobopod, according to a paper published in the journal Communications Biology. It’s the earliest lobopod yet found, and this particular species also marks an evolutionary leap since it’s the first known lobopod to be non-marine.

Lobopods are the evolutionary ancestors to arthropods (insects, spiders, and crustaceans), and their fossils are common along Paleozoic sea beds. Apart from tardigrades and velvet worms, however, they were thought to be confined to oceans. But Palaeocampa anthrax has legs on every trunk, as well as almost 1,000 bristly spines covering its body with orange halos at their tips. Infrared spectroscopy revealed traces of fossilized molecules—likely a chemical that emanated from the spinal tips. Since any chemical defense would just disperse in water, limiting its effectiveness, Knecht concluded that Palaeocampa anthrax was most likely amphibious rather than being solely aquatic.

DOI: Communications Biology, 2025. 10.1038/s42003-025-08483-0 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Research roundup: 7 cool science stories we almost missed Read More »