COVID-19 cleared the skies but also supercharged methane emissions

The remaining question, though, was where all this methane was coming from in the first place. Throughout the pandemic, there was speculation that the surge might be caused by super-emitter events in the oil and gas sector, or perhaps a lack of maintenance on leaky infrastructure during lockdowns.

But the new research suggests that the source of these emissions was not what many expected.

The microbial surge

While the weakened atmospheric sink explained the bulk of the 2020 surge, it wasn’t the only factor at play. The remaining 20 percent of the growth, and an even larger portion of the growth in 2021 and 2022, came from an increase in actual emissions from the ground. To track the source of these emissions down, Peng’s team went through tons of data from satellites and various ground monitoring stations.

Methane comes in different isotopic signatures. Methane from fossil fuels like natural gas leaks or coal mines is heavier, containing a higher fraction of the stable isotope carbon-13. Conversely, methane produced by microbes found in the guts of livestock, in landfills, and most notably in wetlands, is lighter, enriched in carbon-12.

When the researchers analyzed data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration global flask network, a worldwide monitoring system tracking the chemical composition of Earth’s atmosphere, they found that the atmospheric methane during the mysterious surge was becoming significantly lighter. This was a smoking gun for biogenic sources. The surge wasn’t coming from pipes or power plants; it was coming from microbes.

La Niña came to play

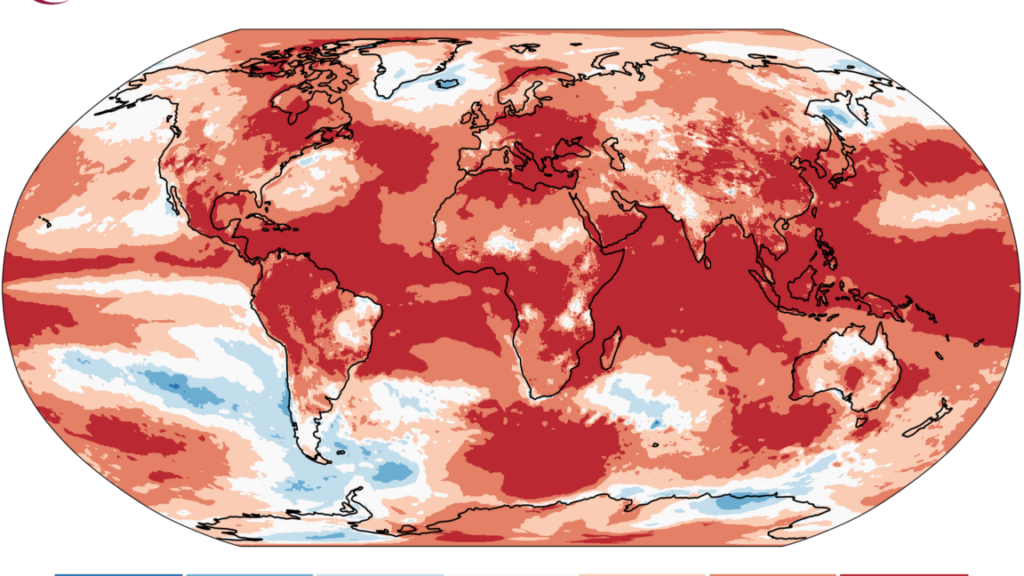

The timing of the pandemic coincided with a relatively rare meteorological event. La Niña, the cool phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation that typically leads to increased rainfall in the tropics, lasted for three consecutive Northern Hemisphere winters (from 2020 to 2023). This made the early 2020s exceptionally wet.

The researchers used satellite data from the Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite and sophisticated atmospheric models to trace the source of the light methane to vast wetland areas in tropical Africa and Southeast Asia. In regions like the Sudd in South Sudan and the Congo Basin, record-breaking rainfall flooded massive swaths of land. In these waterlogged, oxygen-poor environments, microbial methanogens thrived, churning out methane at an accelerated pace.

COVID-19 cleared the skies but also supercharged methane emissions Read More »