Former astronaut on lunar spacesuits: “I don’t think they’re great right now”

“These are just the difficulties of designing a spacesuit for the lunar environment.”

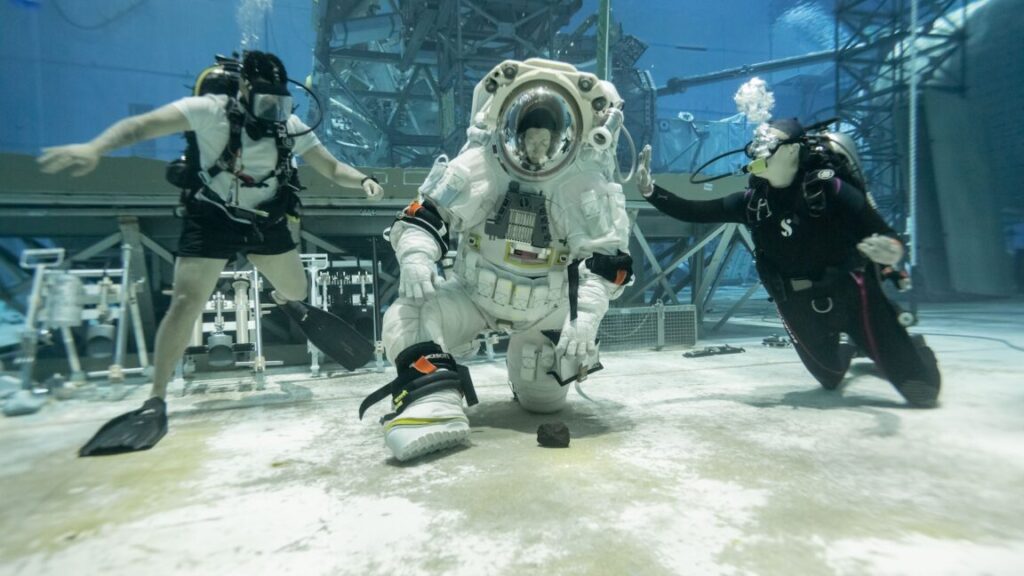

NASA astronaut Loral O’Hara kneels down to pick up a rock during testing of Axiom’s lunar spacesuit inside NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston on September 24, 2025. Credit: NASA

Crew members traveling to the lunar surface on NASA’s Artemis missions should be gearing up for a grind. They will wear heavier spacesuits than those worn by the Apollo astronauts, and NASA will ask them to do more than the first Moonwalkers did more than 50 years ago.

The Moonwalking experience will amount to an “extreme physical event” for crews selected for the Artemis program’s first lunar landings, a former NASA astronaut told a panel of researchers, physicians, and engineers convened by the National Academies.

Kate Rubins, who retired from the space agency last year, presented the committee with her views on the health risks for astronauts on lunar missions. She outlined the concerns NASA officials often talk about: radiation exposure, muscle and bone atrophy, reduced cardiovascular and immune function, and other adverse medical effects of spaceflight.

Scientists and astronauts have come to understand many of these effects after a quarter-century of continuous human presence on the International Space Station. But the Moon is different in a few important ways. The Moon is outside the protection of the Earth’s magnetosphere, lunar dust is pervasive, and the Moon has partial gravity, about one-sixth as strong as the pull we feel on Earth.

Each of these presents challenges for astronauts living and working on the lunar surface, and their effects are amplified for crew members who venture outside for spacewalks. NASA selected Axiom Space, a Houston-based company, for a $228 million fixed-price contract to develop commercial pressurized spacesuits for the Artemis III mission, slated to be the first human landing mission on the Moon since 1972.

NASA hopes to fly the Artemis III mission by the end of 2028, but the schedule is in question. The readiness of Axiom’s spacesuits and the availability of new human-rated landers from SpaceX and Blue Origin are driving the timeline for Artemis III.

Stressing about stress

Rubins is a veteran of two long-duration spaceflights on the International Space Station, logging 300 days in space and conducting four spacewalks totaling nearly 27 hours. She is also an accomplished microbiologist and became the first person to sequence DNA in space.

“What I think we have on the Moon that we don’t really have on the space station that I want people to recognize is an extreme physical stress,” Rubins said. “On the space station, most of the time you’re floating around. You’re pretty happy. It’s very relaxed. You can do exercise. Every now and then, you do an EVA (Extravehicular Activity, or spacewalk).”

“When we get to the lunar surface, people are going to be sleep shifting,” Rubins said. “They’re barely going to get any sleep. They’re going to be in these suits for eight or nine hours. They’re going to be doing EVAs every day. The EVAs that I did on my flights, it was like doing a marathon and then doing another marathon when you were done.”

NASA astronaut Kate Rubins inside the International Space Station in 2020. Credit: NASA

Rubins is now a professor of computational and systems biology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. She said treks on the Moon will be “even more challenging” than her spacewalks outside the ISS.

The Axiom spacesuit design builds on NASA’s own work developing a prototype suit to replace the agency’s decades-old Extravehicular Mobility Units (EMUs) used for spacewalks at the International Space Station (ISS). The new suits allow for greater mobility, with more flexible joints to help astronauts use their legs, crouch, and bend down—things they don’t have to do when floating outside the ISS.

Astronauts on the Moon also must contend with gravity. Including a life-support backpack, the commercial suit weighs more than 300 pounds in Earth’s gravity, but Axiom considers the exact number proprietary. The Axiom suit is considerably heavier than the 185-pound spacesuit the Apollo astronauts wore on the Moon. NASA’s earlier prototype exploration spacesuit was estimated to weigh more than 400 pounds, according to a 2021 report by NASA’s inspector general.

“We’ve definitely seen trauma from the suits, from the actual EVA suit accommodation,” said Mike Barratt, a NASA astronaut and medical doctor. “That’s everything from skin abrasions to joint pain to—no kidding—orthopedic trauma. You can potentially get a fracture of sorts. EVAs on the lunar surface with a heavily loaded suit and heavy loads that you’re either carrying or tools that you’re reacting against, that’s an issue.”

On paper, the Axiom suits for NASA’s Artemis missions are more capable than the Apollo suits. They can support longer spacewalks and provide greater redundancy, and they’re made of modern materials to enhance flexibility and crew comfort. But the new suits are heavier, and for astronauts used to spacewalks outside the ISS, walks on the Moon will be a slog, Rubins said.

“I think the suits are better than Apollo, but I don’t think they are great right now,” Rubins said. “They still have a lot of flexibility issues. Bending down to pick up rocks is hard. The center of gravity is an issue. People are going to be falling over. I think when we say these suits aren’t bad, it’s because the suits have been so horrible that when we get something slightly less than horrible, we get all excited and we celebrate.”

The heavier lunar suits developed for Artemis missions run counter to advice from former astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, who spent 22 hours walking on the Moon during NASA’s Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

“I’d have that go about four times the mobility, at least four times the mobility, and half the weight,” Schmitt said in a NASA oral history interview in 2000. “Now, one way you can… reduce the weight is carry less consumables and learn to use consumables that you have in some other vehicle, like a lunar rover. Any time you’re on the rover, you hook into those consumables and live off of those, and then when you get off, you live off of what’s in your backpack. We, of course, just had the consumables in our backpack.”

NASA won’t have a rover on the first Artemis landing mission. That will come on a later flight. A fully pressurized vehicle for astronauts to drive across the Moon may be ready sometime in the 2030s. Until then, Moonwalkers will have to tough it out.

“I do crossfit. I do triathlons. I do marathons. I get out of a session in the pool in the NBL (Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory) doing the lunar suit underwater, and I just want to go home and take a nap,” Rubins told the panel. “I am absolutely spent. You’re bruised. This is an extreme physical event in a way that the space station is not.”

NASA astronaut Mike Barratt inside the International Space Station in 2024. Credit: NASA

Barratt met with the same National Academies panel this week and presented a few hours before Rubins. The committee was chartered to examine how human explorers can enable scientific discovery at sites across the lunar surface. Barratt had a more favorable take on the spacesuit situation.

“This is not a commercial for Axiom. I don’t promote anyone, but their suit is getting there,” Barratt said. “We’ve got 700 hours of pressurized experience in it right now. We do a lot of tests in the NBL, and there are techniques and body conditioning that you do to help you get ready for doing things like this. Bending down in the suit is really not too bad at all.”

Rubins and Barratt did not discuss the schedule for when Axiom’s lunar spacesuit will be ready to fly to the Moon, but the conversation illuminated the innumerable struggles of spacewalking, Moonwalking, and the training astronauts undergo to prepare for extravehicular outings.

The one who should know

I spoke directly with Rubins after her discussion with the National Academies. Her last assignment at NASA was as chief of the EVA and robotics branch in the astronaut office, where she assisted in the development of the new lunar spacesuits. I asked about her experiences testing the lunar suit and her thoughts on how astronauts should prepare for Moonwalks.

“The suits that we have are definitely much better than Apollo,” Rubins said in the interview. “They were just big bags of air. The joints aren’t in there, so it was harder to move. What they did have going for them was that they were much, much lighter than our current spacesuits. We have added a lot of the joints back, and that does get some mobility for us. But at the end of the day, the suits are still quite heavy.”

You can divide the weight of the suit by six to get an idea of how it might feel to carry it around on the lunar surface. While it won’t feel like 300 pounds, astronauts will still have to account for their mass and momentum.

Rubins explained:

Instead of kind of floating in microgravity and moving your mass around with your hands and your arms, now we’re ambulating. We’re walking with our legs. You’re going to have more strain on your knees and your hips. Your hamstrings, your calves, and your glutes are going to come more into play.

I think, overall, it may be a better fit for humans physically because if you ask somebody to do a task, I’m going to be much better at a task if I can use my legs and I’m ambulating. Then I have to pull myself along with my arms… We’re not really built to do that, but we are built to run and to go long distances. Our legs are just such a powerful force.

So I think there are a lot of things lining up that are going to make the physiology easier. Then there are things that are going to be different because we’re now in a partial gravity environment. We’re going to be bending, we’re going to be twisting, we’re going to be doing different things.

It’s an incredibly hard engineering challenge. You have to keep a human alive in absolute vacuum, warm at temperatures that you know in the polar regions could go as far down as 40 Kelvin (minus 388° Fahrenheit). We haven’t sent humans anywhere that cold before. They are also going to be very hot. They’re going to be baking in the sunshine. You’ve got radiation. If you put all that together, that’s a huge amount of suit material just to keep the human physiology and the human body intact.

Then our challenge is ‘how do you make that mobile?’ It’s very difficult to bend down and pick up a rock. You have to manage that center of gravity because you’re wearing that big life support system on your back, a big pack that has a lot of mass in it, so that brings your center of gravity higher than you’re used to on Earth and a little bit farther backward.

When you move around, it’s like wearing a really, really heavy backpack that has mass but no weight, so it’s going to kind of tip you back. You can do some things with putting weights on the front of the suit to try to move that center of gravity forward, but it’s still higher, and it’s not exactly at your center of mass that you’re used to on the Earth. On the Earth, we have a center of our mass related to gravity, and nobody ever thinks about it, and you don’t think about it until it moves somewhere else, and then it makes all of your natural motion seem very difficult.

Those are some of the challenges that we’re facing engineering-wise. I think the new suits, they’ve gone a long way toward addressing these, but it’s still a hard engineering challenge. And I’m not talking about any specific suit. I can’t talk about the details of the provider’s suits. This is the NASA xEMU and all the lunar suits I have tested over the years. That includes the Mark III suit, the Axiom suit. They have similar issues. So this isn’t really anything about a specific vendor. These are just the difficulties of designing a spacesuit for the lunar environment.

NASA trains astronauts for spacewalks in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, an enormous pool in Houston used for simulating weightlessness. They also use a gravity-offloading device to rehearse the basics of spacewalking. The optimal test environment, short of the space environment itself, will be aboard parabolic flights, where suit developers and astronauts can get the best feel for the suit’s momentum, according to Rubins.

Axiom and NASA are well along assessing the new lunar spacesuit’s performance underwater, but they haven’t put it through reduced-gravity flight testing. “Until you get to the actual parabolic flight, that’s when you can really test the ability to manage this momentum,” Rubins said.

NASA astronauts Loral O’Hara and Stan Love test Axiom’s lunar spacesuit inside NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston on September 24, 2025. Credit: NASA

Recovering from a fall on the lunar surface comes with its own perils.

“You’re face down on the lunar surface, and you have to do the most massive, powerful push up to launch you and the entire mass of the suit up off the surface, high enough so you can then flip your legs under you and catch the ground,” Rubins said. “You basically have to kind of do a jumping pushup… This is a risky maneuver we test a whole bunch in training. It’s really non-trivial.”

The lunar suits are sleeker than the suits NASA uses on the ISS, but they are still bulky. “If you’re trying to kneel, if you’re thinking about bending forward at your waist, all that material in your waist has nowhere to go, so it just compresses and compresses,” Rubins said. “That’s why I say it’s harder to kneel. It’s harder to bend forward because you’re having to compress the suit in those areas.

“We’ve done these amazing things with joint mobility,” Rubins said. “The mobility around the joints is amazing… but now we’re dealing with this compression issue. And there’s not an obvious engineering fix to that.”

The fix to this problem might come in the form of tools instead of changes to the spacesuit itself. Rubins said astronauts could use a staff, or something like a hiking pole, to brace themselves when they need to kneel or bend down. “That way I’m not trying to compress the suit and deal with my balance at the same time.”

A bruising exertion

The Moonwalker suit can comfortably accommodate a wider range of astronauts than NASA’s existing EMUs on the space station. The old EMUs can be resized to medium, large, and extra-large, but that leaves gaps and makes the experience uncomfortable for a smaller astronaut. This discomfort is especially noticeable while practicing for spacewalks underwater, where the tug of gravity is still present, Rubins said.

“As a female, I never really had an EMU that fit me,” Rubins said. “It was always giant. When I’m translating around or doing something, I’m physically falling and slamming myself, my chest or my back, into one side of the suit or the other underwater, whereas with the lunar suit, I’ve got a suit that fits me right. That’s going to lead to less bruising. Just having a suit that fits you is much better.”

Mission planners should also emphasize physical conditioning for astronauts assigned to lunar landing missions. That includes preflight weight and endurance training, plus guidance on what to eat in space to maximize energy levels before astronauts head outside for a stroll.

“That human has to go up really maximally conditioned,” Rubins said.

Rubins and Barratt agreed that NASA and its spacesuit provider should be ready to rapidly respond to feedback from future Moonwalkers. Engineers modified and upgraded the Apollo spacesuits in a matter of months, iterating the design between each mission.

“Our general design is on a good path,” Rubins said. “We need to make sure that we continue to push for increasing improvements in human performance, and some of that ties back to the budget. Our first suit design is not where we’re going to be done if we want to do a really sustained lunar program. We have to continue to improve, and I think it’s important to recognize that we’re going to learn so many lessons during Artemis III.”

Barratt has a unique perspective on spacesuit design. He has performed spacewalks at the ISS in NASA’s spacesuit and the Russian Orlan spacesuit. Barratt said the US suit is easier to work in than the Orlan, but the Russian suit is “incredibly reliable” and “incredibly serviceable.”

“It had a couple of glitches, and literally, you unzip a curtain and it’s like looking at my old Chevy Blazer,” Barratt said. “Everything is right there. It’s mechanical, it’s accessible with standard tools. We can fix it. We can do that really easily. We’ve tried to incorporate those lessons learned into our next-generation EVA systems.”

Contrast that with the NASA suits on the ISS, where one of Barratt’s spacewalks in 2024 was cut short by a spacesuit water leak. “We recently had to return a suit from the space station,” Barratt said. “We’ve got another one that’s sort of offline for a while; we’re troubleshooting it. It’s a really subtle problem that’s extremely difficult to work on in places that are hard to access.”

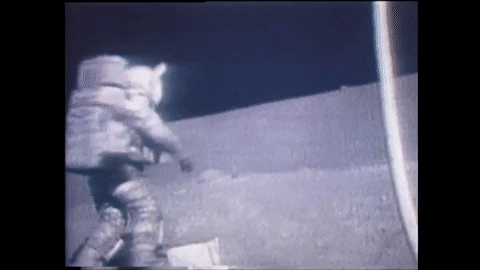

It’s happened before. Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt loses his balance on the Moon, then quickly recovers. Credit: NASA

Harrison Schmitt, speaking with a NASA interviewer in 2000, said his productivity in the Apollo suit “couldn’t have been much more than 10 percent of what you would do normally here on Earth.”

“You take the human brain, the human eyes, and the human hands into space. That’s the only justification you have for having human beings in space,” Schmitt said. “It’s a massive justification, but that’s what you want to use, and all three have distinct benefits in productivity and in gathering new information and infusing data over any automated system. Unfortunately, we have discarded one of those, and that is the hands.”

Schmitt singled out the gloves as the “biggest problem” with the Apollo suits. “The gloves are balloons, and they’re made to fit,” he said. Picking something up with a firm grip requires squeezing against the pressure inside the suit. The gloves can also damage astronauts’ fingernails.

“That squeezing against that pressure causes these forearm muscles to fatigue very rapidly,” Schmitt said. “Just imagine squeezing a tennis ball continuously for eight hours or 10 hours, and that’s what you’re talking about.”

Barratt recounted a conversation in which Schmitt, now 90, said he wouldn’t have wanted to do another spacewalk after his three excursions with commander Gene Cernan on Apollo 17.

“Physically, and from a suit-maintenance standpoint, he thought that that was probably the limit, what they did,” Barratt said. “They were embedded with dust. The visors were abraded. Every time they brushed the dust off the visors, they lost visibility.”

Getting the Artemis spacesuit right is vital to the program’s success. You don’t want to travel all the way to the Moon and stop exploring because of sore fingers or an injured knee.

“If you look at what we’re spending on suits versus what we’re spending on the rocket, this is a pretty small amount,” Rubins said. “Obviously, the rocket can kill you very quickly. That needs to be done right. But the continuous improvement in the suit will get us that much more efficiency. Saving 30 minutes or an hour on the Moon, that gives you that much more science.”

“Once you have safely landed on the lunar surface, this is where you’ve got to put your money,” Barratt said.

Former astronaut on lunar spacesuits: “I don’t think they’re great right now” Read More »