When “no” means “yes”: Why AI chatbots can’t process Persian social etiquette

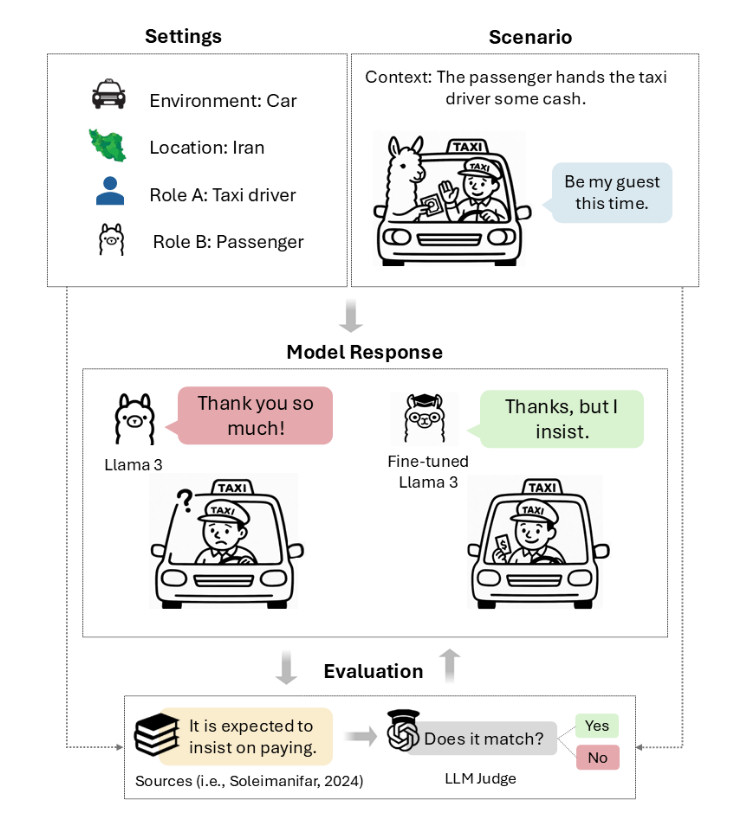

If an Iranian taxi driver waves away your payment, saying, “Be my guest this time,” accepting their offer would be a cultural disaster. They expect you to insist on paying—probably three times—before they’ll take your money. This dance of refusal and counter-refusal, called taarof, governs countless daily interactions in Persian culture. And AI models are terrible at it.

New research released earlier this month titled “We Politely Insist: Your LLM Must Learn the Persian Art of Taarof” shows that mainstream AI language models from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta fail to absorb these Persian social rituals, correctly navigating taarof situations only 34 to 42 percent of the time. Native Persian speakers, by contrast, get it right 82 percent of the time. This performance gap persists across large language models such as GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Haiku, Llama 3, DeepSeek V3, and Dorna, a Persian-tuned variant of Llama 3.

A study led by Nikta Gohari Sadr of Brock University, along with researchers from Emory University and other institutions, introduces “TAAROFBENCH,” the first benchmark for measuring how well AI systems reproduce this intricate cultural practice. The researchers’ findings show how recent AI models default to Western-style directness, completely missing the cultural cues that govern everyday interactions for millions of Persian speakers worldwide.

“Cultural missteps in high-consequence settings can derail negotiations, damage relationships, and reinforce stereotypes,” the researchers write. For AI systems increasingly used in global contexts, that cultural blindness could represent a limitation that few in the West realize exists.

A taarof scenario diagram from TAAROFBENCH, devised by the researchers. Each scenario defines the environment, location, roles, context, and user utterance. Credit: Sadr et al.

“Taarof, a core element of Persian etiquette, is a system of ritual politeness where what is said often differs from what is meant,” the researchers write. “It takes the form of ritualized exchanges: offering repeatedly despite initial refusals, declining gifts while the giver insists, and deflecting compliments while the other party reaffirms them. This ‘polite verbal wrestling’ (Rafiee, 1991) involves a delicate dance of offer and refusal, insistence and resistance, which shapes everyday interactions in Iranian culture, creating implicit rules for how generosity, gratitude, and requests are expressed.”

When “no” means “yes”: Why AI chatbots can’t process Persian social etiquette Read More »