IBM now describing its first error-resistant quantum compute system

Company is moving past focus on qubits, shifting to functional compute units.

A rendering of what IBM expects will be needed to house a Starling quantum computer. Credit: IBM

On Tuesday, IBM released its plans for building a system that should push quantum computing into entirely new territory: a system that can both perform useful calculations while catching and fixing errors and be utterly impossible to model using classical computing methods. The hardware, which will be called Starling, is expected to be able to perform 100 million operations without error on a collection of 200 logical qubits. And the company expects to have it available for use in 2029.

Perhaps just as significant, IBM is also committing to a detailed description of the intermediate steps to Starling. These include a number of processors that will be configured to host a collection of error-corrected qubits, essentially forming a functional compute unit. This marks a major transition for the company, as it involves moving away from talking about collections of individual hardware qubits and focusing instead on units of functional computational hardware. If all goes well, it should be possible to build Starling by chaining a sufficient number of these compute units together.

“We’re updating [our roadmap] now with a series of deliverables that are very precise,” IBM VP Jay Gambetta told Ars, “because we feel that we’ve now answered basically all the science questions associated with error correction and it’s becoming more of a path towards an engineering problem.”

New architectures

Error correction on quantum hardware involves entangling a group of qubits in a way that distributes one or more quantum bit values among them and includes additional qubits that can be used to check the state of the system. It can be helpful to think of these as data and measurement qubits. Performing weak quantum measurements on the measurement qubits produces what’s called “syndrome data,” which can be interpreted to determine whether anything about the data qubits has changed (indicating an error) and how to correct it.

There are lots of potential ways to arrange different combinations of data and measurement qubits for this to work, each referred to as a code. But, as a general rule, the more hardware qubits committed to the code, the more robust it will be to errors, and the more logical qubits that can be distributed among its hardware qubits.

Some quantum hardware, like that based on trapped ions or neutral atoms, is relatively flexible when it comes to hosting error-correction codes. The hardware qubits can be moved around so that any two can be entangled, so it’s possible to adopt a huge range of configurations, albeit at the cost of the time spent moving atoms around. IBM’s technology is quite different. It relies on qubits made of superconducting electronics laid out on a chip, with entanglement mediated by wiring that runs between qubits. The layout of this wiring is set during the chip’s manufacture, and so the chip’s design commits it to a limited number of potential error-correction codes.

Unfortunately, this wiring can also enable crosstalk between neighboring qubits, causing them to lose their state. To avoid this, existing IBM processors have their qubits wired in what they term a “heavy hex” configuration, named for its hexagonal arrangements of connections among its qubits. This has worked well to keep the error rate of its hardware down, but it also poses a challenge, since IBM has decided to go with an error-correction code that’s incompatible with the heavy hex geometry.

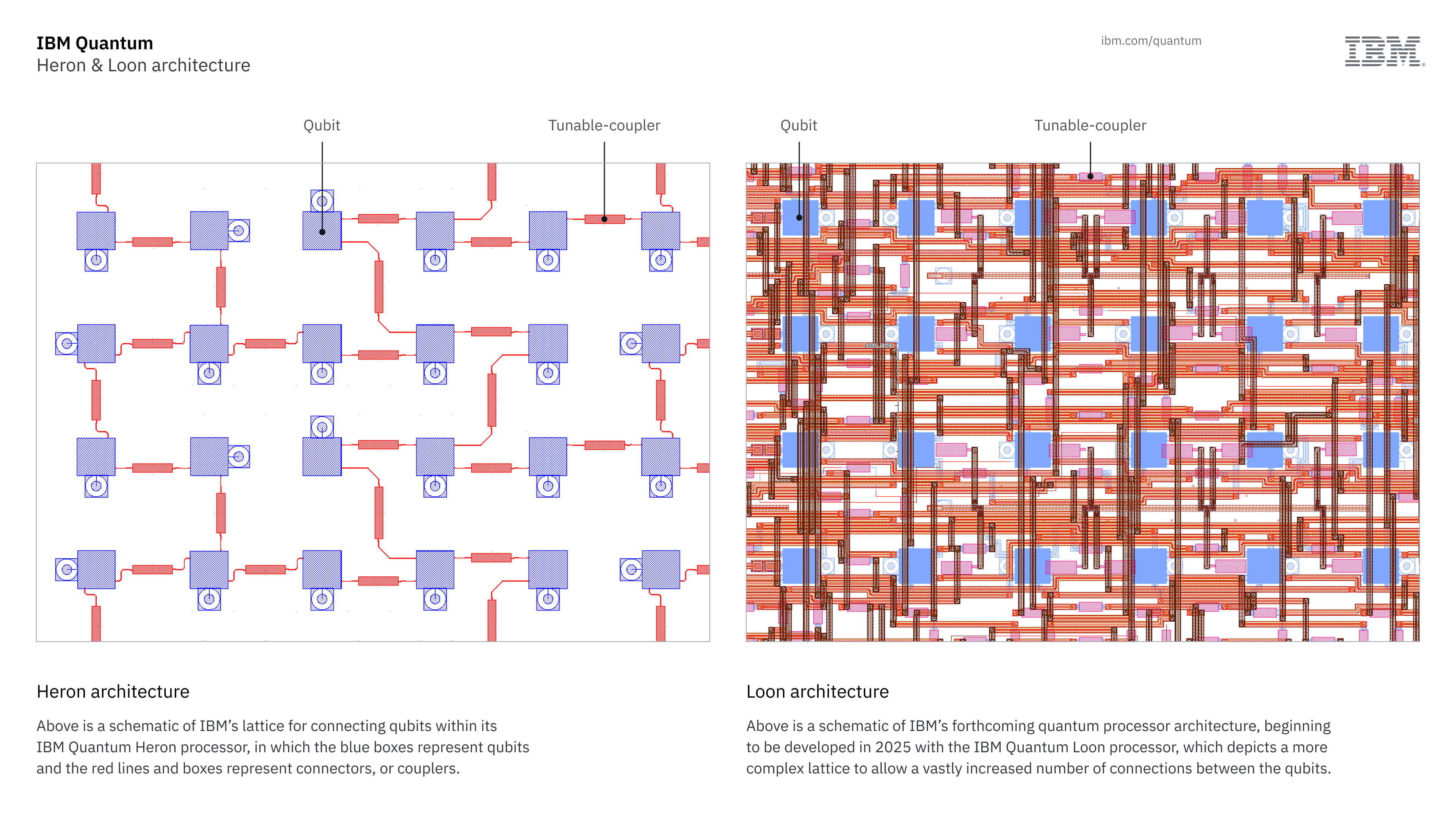

A couple of years back, an IBM team described a compact error correction code called a low-density parity check (LDPC). This requires a square grid of nearest-neighbor connections among its qubits, as well as wiring to connect qubits that are relatively distant on the chip. To get its chips and error-correction scheme in sync, IBM has made two key advances. The first is in its chip packaging, which now uses several layers of wiring sitting above the hardware qubits to enable all of the connections needed for the LDPC code.

We’ll see that first in a processor called Loon that’s on the company’s developmental roadmap. “We’ve already demonstrated these three things: high connectivity, long-range couplers, and couplers that break the plane [of the chip] and connect to other qubits,” Gambetta said. “We have to combine them all as a single demonstration showing that all these parts of packaging can be done, and that’s what I want to achieve with Loon.” Loon will be made public later this year.

On the left, the simple layout of the connections in a current-generation Heron processor. At right, the complicated web of connections that will be present in Loon. Credit: IBM

The second advance IBM has made is to eliminate the crosstalk that the heavy hex geometry was used to minimize, so heavy hex will be going away. “We are releasing this year a bird for near-term experiments that is a square array that has almost zero crosstalk,” Gambetta said, “and that is Nighthawk.” The more densely connected qubits cut the overhead needed to perform calculations by a factor of 15, Gambetta told Ars.

Nighthawk is a 2025 release on a parallel roadmap that you can think of as user-facing. Iterations on its basic design will be released annually through 2028, each enabling more operations without error (going from 5,000 gate operations this year to 15,000 in 2028). Each individual Nighthawk processor will host 120 hardware qubits, but 2026 will see three of them chained together and operating as a unit, providing 360 hardware qubits. That will be followed in 2027 by a machine with nine linked Nighthawk processors, boosting the hardware qubit number over 1,000.

Riding the bicycle

The real future of IBM’s hardware, however, will be happening over on the developmental line of processors, where talk about hardware qubit counts will become increasingly irrelevant. In a technical document released today, IBM is describing the specific LDPC code it will be using, termed a bivariate bicycle code due to some cylindrical symmetries in its details that vaguely resemble bicycle wheels. The details of the connections matter less than the overall picture of what it takes to use this error code in practice.

IBM describes two implementations of this form of LDPC code. In the first, 144 hardware qubits are arranged so that they play host to 12 logical qubits and all of the measurement qubits needed to perform error checks. The standard measure of a code’s ability to catch and correct errors is called its distance, and in this case, the distance is 12. As an alternative, they also describe a code that uses 288 hardware qubits to host the same 12 logical qubits but boost the distance to 18, meaning it’s more resistant to errors. IBM will make one of these collections of logical qubits available as a Kookaburra processor in 2026, which will use them to enable stable quantum memory.

The follow-on will bundle these with a handful of additional qubits that can produce quantum states that are needed for some operations. Those, plus hardware needed for the quantum memory, form a single, functional computation unit, built on a single chip, that is capable of performing all the operations needed to implement any quantum algorithm.

That will appear with the Cockatoo chip, which will also enable multiple processing units to be linked on a single bus, allowing the logical qubit count to grow beyond 12. (The company says that one of the dozen logical qubits in each unit will be used to mediate entanglement with other units and so won’t be available for computation.) That will be followed by the first test versions of Starling, which will allow universal computations on a limited number of logical qubits spread across multiple chips.

Separately, IBM is releasing a document that describes a key component of the system that will run on classical computing hardware. Full error correction requires evaluating the syndrome data derived from the state of all the measurement qubits in order to determine the state of the logical qubits and whether any corrections need to be made. As the complexity of the logical qubits grows, the computational burden of evaluating grows with it. If this evaluation can’t be executed in real time, then it becomes impossible to perform error-corrected calculations.

To address this, IBM has developed a message-passing decoder that can perform parallel evaluations of the syndrome data. The system explores more of the solution space by a combination of randomizing the weight given to the memory of past solutions and by handing any seemingly non-optimal solutions on to new instances for additional evaluation. The key thing is that IBM estimates that this can be run in real time using FPGAs, ensuring that the system works.

A quantum architecture

There are a lot more details beyond those, as well. Gambetta described the linkage between each computational unit—IBM is calling it a Universal Bridge—which requires one microwave cable for each code distance of the logical qubits being linked. (In other words, a distance 12 code would need 12 microwave-carrying cables to connect each chip.) He also said that IBM is developing control hardware that can operate inside the refrigeration hardware, based on what they’re calling “cold CMOS,” which is capable of functioning at 4 Kelvin.

The company is also releasing renderings of what it expects Starling to look like: a series of dilution refrigerators, all connected by a single pipe that contains the Universal Bridge. “It’s an architecture now,” Gambetta said. “I have never put details in the roadmap that I didn’t feel we could hit, and now we’re putting a lot more details.”

The striking thing to me about this is that it marks a shift away from a focus on individual qubits, their connectivity, and their error rates. The error hardware rates are now good enough (4 x 10-4) for this to work, although Gambetta felt that a few more improvements should be expected. And connectivity will now be directed exclusively toward creating a functional computational unit.

That said, there’s still a lot of space beyond Starling on IBM’s roadmap. The 200 logical qubits it promises will be enough to handle some problems, but not enough to perform the complex algorithms needed to do things like break encryption. That will need to wait for something closer to Blue Jay, a 2033 system that IBM expects will have 2,000 logical qubits. And, as of right now, it’s the only thing listed beyond Starling.

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

IBM now describing its first error-resistant quantum compute system Read More »