NASA will soon find out if the Perseverance rover can really persevere on Mars

Engineers at JPL are certifying the Perseverance rover to drive up to 100 kilometers.

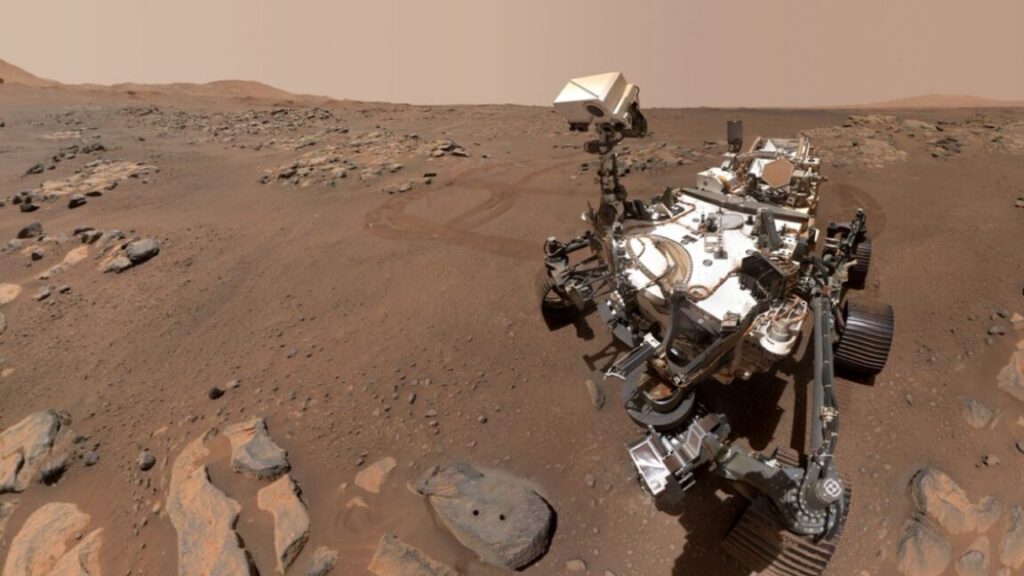

The Perseverance rover looks back on its tracks on the floor of Jezero Crater in 2022. Credit: NASA/JPL

When the Perseverance rover arrived on Mars nearly five years ago, NASA officials thought the next American lander to take aim on the red planet would be taking shape by now.

At the time, the leaders of the space agency expected this next lander could be ready for launch as soon as 2026—or more likely in 2028. Its mission would have been to retrieve Martian rock specimens collected by the Perseverance rover, then billed as the first leg of a multilaunch, multibillion-dollar Mars Sample Return campaign.

Here we are on the verge of 2026, and there’s no sample retrieval mission nearing the launch pad. In fact, no one is building such a lander at all. NASA’s strategy for a Mars Sample Return, or MSR, mission remains undecided after the projected cost of the original plan ballooned to $11 billion. If MSR happens at all, it’s now unlikely to launch until the 2030s.

That means the Perseverance rover, which might have to hand off the samples to a future retrieval lander in some circumstances, must continue weathering the harsh, cold, dusty environment of Mars. The good news is that the robot, about the size of a small SUV, is in excellent health, according to Steve Lee, Perseverance’s deputy project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

“Perseverance is approaching five years of exploration on Mars,” Lee said in a press briefing Wednesday at the American Geophysical Union’s annual fall meeting. “Perseverance is really in excellent shape. All the systems onboard are operational and performing very, very well. All the redundant systems onboard are available still, and the rover is capable of supporting this mission for many, many years to come.”

The rover’s operators at JPL are counting on sustaining Perseverance’s good health. The rover’s six wheels have carried it a distance of about 25 miles, or 40 kilometers, since landing inside the 28-mile-wide (45-kilometer) Jezero Crater in February 2021. That is double the original certification for the rover’s mobility system and farther than any vehicle has traveled on the surface of another world.

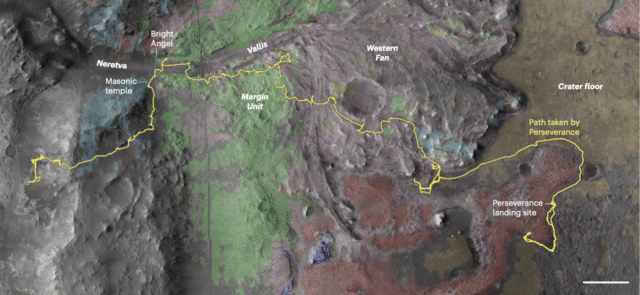

This enhanced-color mosaic is made from three separate images taken on September 8, 2025, each of which was acquired using the Perseverance rover’s Mastcam-Z instrument. The images were processed to improve visual contrast and enhance color differences. The view shows a location known as “Mont Musard” and another region named “Lac de Charmes,” where the rover’s team will be looking for more rock core samples to collect in the year ahead. The mountains in the distance are approximately 52 miles (84 kilometers) away.

Going for 100

Now, engineers are asking Perseverance to perform well beyond expectations. An evaluation of the rover’s health concluded it can operate until at least 2031. The rover uses a radioactive plutonium power source, so it’s not in danger of running out of electricity or fuel any time soon. The Curiosity rover, which uses a similar design, has surpassed 13 years of operations on Mars.

There are two systems that are most likely to limit the rover’s useful lifetime. One is the robotic arm, which is necessary to collect samples, and the other is the rover’s six wheels and the drive train that powers them.

“To make sure we can continue operations and continue driving for a long, long way, up to 100 kilometers (62 miles), we are doing some additional testing,” Lee said. “We’ve successfully completed a rotary actuator life test that has now certified the rotary system to 100 kilometers for driving, and we have similar testing going on for the brakes. That is going well, and we should finish those early part of next year.”

Ars asked Lee why JPL decided on 100 kilometers, which is roughly the same distance as the average width of Lake Michigan. Since its arrival in 2021, Perseverance has climbed out of Jezero Crater and is currently exploring the crater’s rugged rim. If NASA sends a lander to pick up samples from Perseverance, the rover will have to drive back to a safe landing zone for a handoff.

“We actually had laid out a traverse path exploring the crater rim, much more of the crater rim than we have so far, and then be able to return to a rendezvous site,” Lee said. “So we did an estimate of the total mission drive duration to complete that mission, added margin for science exploration, added margin in case we need the rendezvous at a different site… and it just turned out to add up to a nice, even 100 kilometers.”

The time-lapse video embedded below shows the Perseverance rover’s record-breaking 1,351-foot (412-meter) drive on June 19, 2025.

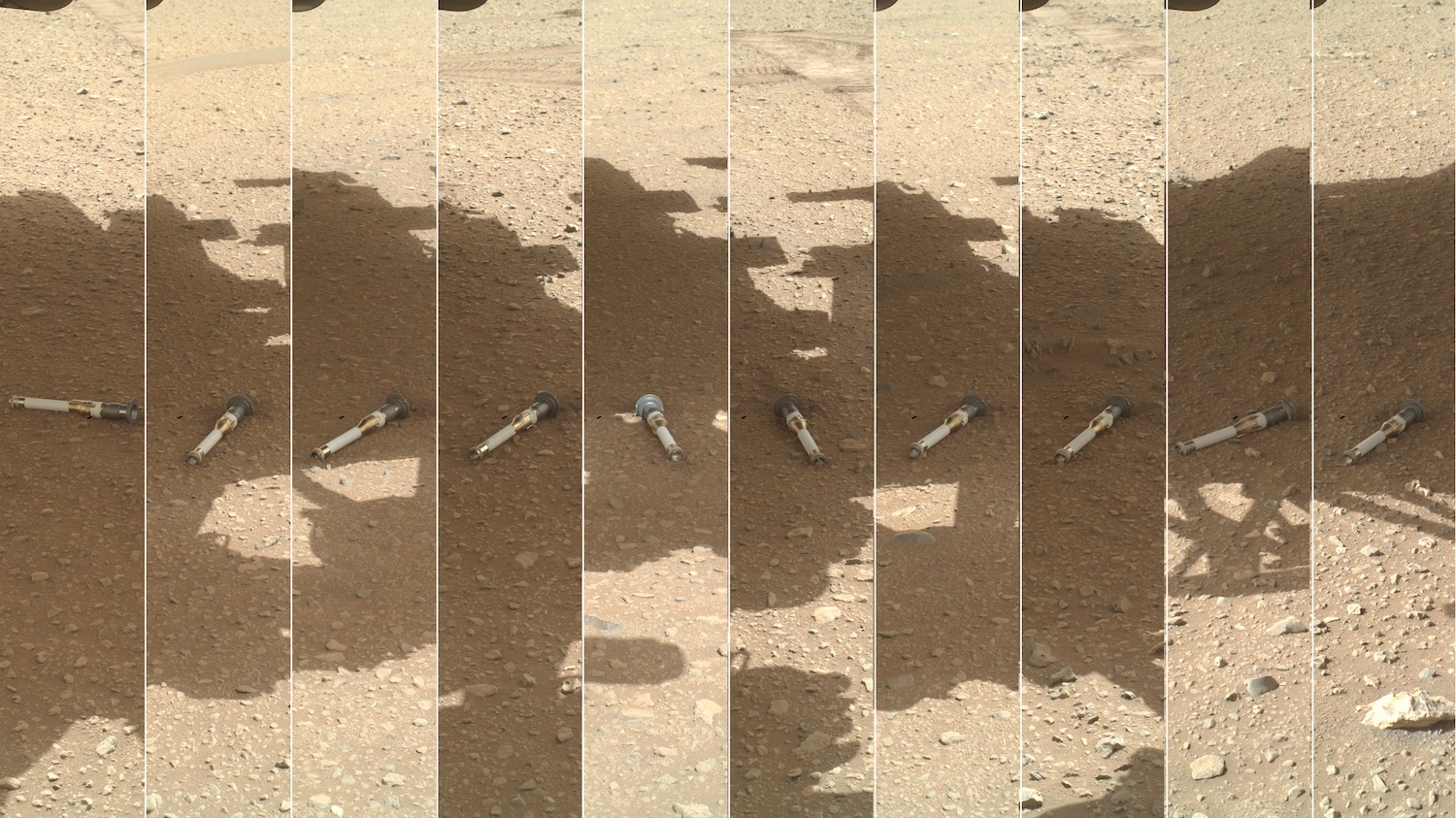

Despite the disquiet on the future of MSR, the Perseverance rover has dutifully collected specimens and placed them in 33 titanium sample tubes since arriving on Mars. Perseverance deposited some of the sealed tubes on the surface of Mars in late 2022 and early 2023 and has held onto the remaining containers while continuing to drive toward the rim of Jezero.

The dual-depot approach preserves the option for future MSR mission planners to go after either batch of samples.

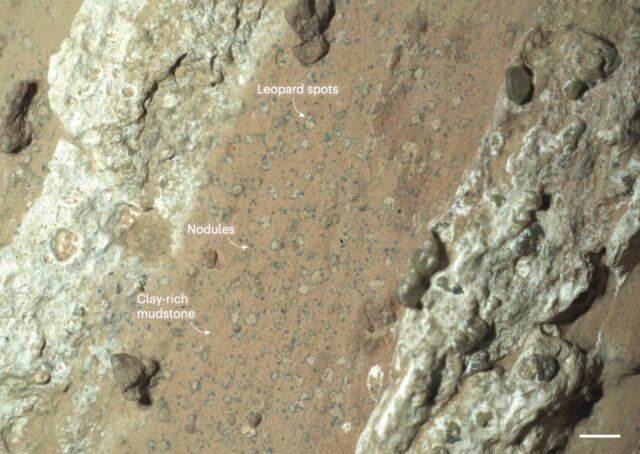

Scientists selected Jezero as the target for the Perseverance mission because they suspected it was the site of an ancient dried-up river delta with a surplus of clay-rich minerals. The rover’s instruments confirmed this hypothesis, finding sediments in the crater floor that were deposited at the bottom of a lake of liquid water billions of years ago, including sandstones and mudstones known to preserve fossilized life in comparable environments on Earth.

A research team published findings in the journal Nature in September describing the discovery of chemical signatures and structures in a rock that could have been formed by ancient microbial life. Perseverance lacks the bulky, sprawling instrumentation to know for sure, so ground teams ordered the rover to collect a pulverized specimen from the rock in question and seal it for eventual return to Earth.

Fill but don’t seal

Lee said Perseverance will continue filling sample tubes in the expectation that they will eventually come back to Earth.

“We do expect to continue some sampling,” Lee said. “We have six open sample tubes, unused sample tubes, onboard. We actually have two that we took samples and didn’t seal yet. So we have options of maybe replacing them if we’re finding that there’s even better areas that we want to collect from.”

The rover’s management team at JPL is finalizing the plan for Perseverance through 2028. Lee expects the rover will remain at Jezero’s rim for a while. “There are quite a number of very prime, juicy targets we would love to go explore,” he said.

In the meantime, if Perseverance runs across an alluring rock, scientists will break out the rover’s coring drill and fill more tubes.

“We certainly have more than enough to keep us busy, and we are not expecting a major perturbation to our science explorations in the next two and a half years as a result of sample return uncertainty,” Lee said.

Perseverance has its own suite of sophisticated instruments. The instruments can’t do what labs on Earth can, but the rover can scan rocks to determine what they’re made of, search for life-supporting organic molecules, map underground geology, and capture startling vistas that inspire and inform.

This photo montage shows sample tubes shortly after they were deposited onto the surface by NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover in late 2022 and early 2023. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

The rover’s sojourn along the Jezero Crater rim is taking it through different geological eras, from the time Jezero harbored a lake to its formation at an even earlier point in Martian history. Fundamentally, researchers are asking the question “What was it like if you were a microbe living on the surface of Mars?” said Briony Horgan, a mission scientist at Purdue University.

Along the way, the rover will stop and do a sample collection if something piques the science team’s interest.

“We are adopting a strategy, in many cases, to fill a tube, and we have the option to not seal it,” Lee said. “Most of our tubes are sealed, but we have the option to not seal it, and that gives us a flexibility downstream to replace the sample if there’s one that we find would make an even stronger representative of the diversity we are discovering.”

An indefinite wait

Planetary scientists have carefully curated the specimens cached by the Perseverance rover. The samples are sorted for their discovery potential, with an emphasis on the search for ancient microbial life. That’s why Perseverance was sent to Jezero in the first place.

China is preparing its own sample-return mission, Tianwen-3, for launch as early as 2028, aiming to deliver Mars rocks back to Earth by 2031. If the Tianwen-3 mission keeps to this schedule—and is successful—China will almost certainly be first to pull off the achievement. Officials have not announced the landing site for Tianwen-3, so the jury is still out on the scientific value of the rocks China aims to bring back.

NASA’s original costly architecture for Mars Sample Return would have used a lander built by JPL and a small solid-fueled rocket to launch the rock samples back into space after collecting them from the Perseverance rover. The capsule containing the Mars rocks would then transfer them to another spacecraft in orbit around Mars. Once Earth and Mars reached the proper orbital alignment, the return spacecraft would begin the journey home. All told, the sample return campaign would last several years.

NASA asked commercial companies to develop their own ideas for Mars Sample Return in 2024. SpaceX, Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, and Rocket Lab submitted their lower-cost commercial concepts to NASA, but progress stalled there. NASA’s former administrator, Bill Nelson, punted on a decision on what to do next with Mars Sample Return in the final weeks of the Biden administration.

A few months later, the new Trump administration proposed outright canceling the Mars Sample Return mission. Mars Sample Return, known as MSR, was ranked as the top priority for planetary science in a National Academies decadal survey. Researchers say they could learn much more about Mars and the possibilities of past life there by bringing samples back to Earth for analysis.

Budget writers in the House of Representatives voted to restore funding for Mars Sample Return over the summer, but the Senate didn’t explicitly weigh in on the mission. NASA is now operating under a stopgap budget passed by Congress last month, and MSR remains in limbo.

There are good arguments for going with a commercial sample-return mission, using a similar approach to the one NASA used to buy commercial cargo and crew transportation services for the International Space Station. NASA might also offer prizes or decide to wait for a human expedition to Mars for astronauts to scoop up samples by hand.

Eric Berger, senior space editor at Ars, discussed these options a few months ago. After nearly a year of revolving-door leadership, NASA finally got a Senate-confirmed administrator this week. It will now be up to the new NASA chief, Jared Isaacman, to chart a new course for Mars Sample Return.

NASA will soon find out if the Perseverance rover can really persevere on Mars Read More »