Painted altar in Maya city of Tikal reveals aftermath of ancient coup

It’s always about colonialism

The altar marks the presence of an enclave of foreign elites from Teotihuacan.

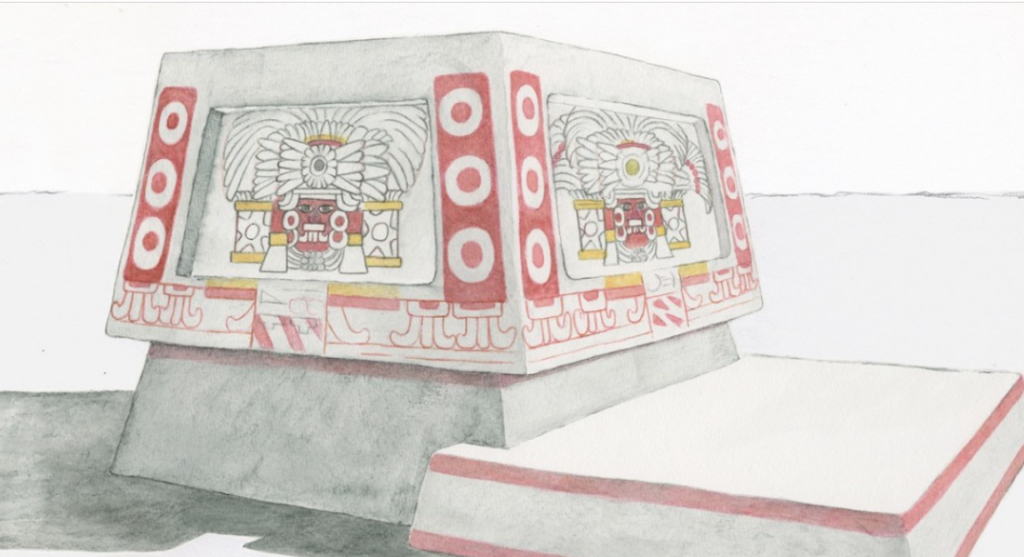

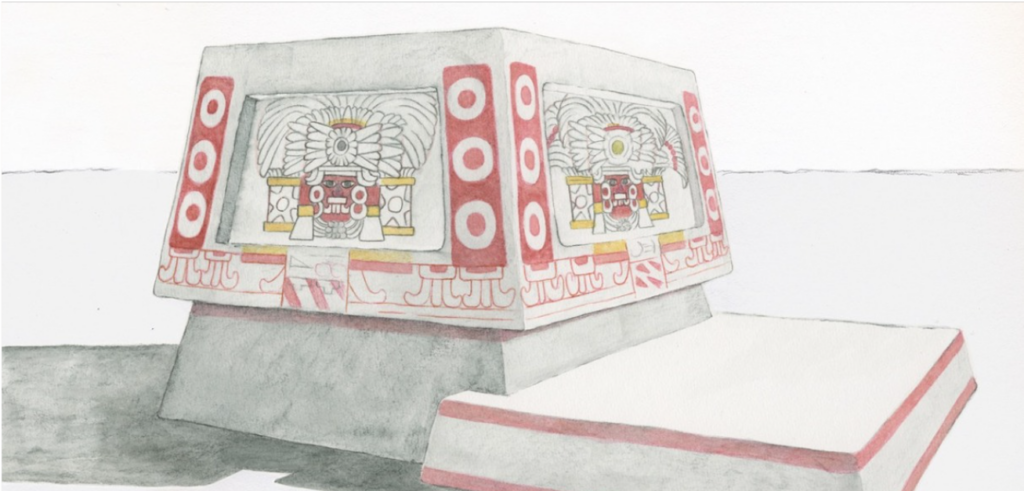

This rendering shows what the altar might have looked like in its heyday. Credit: Heather Hurst

A family altar in the Maya city of Tikal offers a glimpse into events in an enclave of the city’s foreign overlords in the wake of a local coup.

Archaeologists recently unearthed the altar in a quarter of the Maya city of Tikal that had lain buried under dirt and rubble for about the last 1,500 years. The altar—and the wealthy household behind the courtyard it once adorned—stands just a few blocks from the center of Tikal, one of the most powerful cities of Maya civilization. But the altar and the courtyard around it aren’t even remotely Maya-looking; their architecture and decoration look like they belong 1,000 kilometers to the west in the city of Teotihuacan, in central Mexico.

The altar reveals the presence of powerful rulers from Teotihuacan who were there at a time when a coup ousted Tikal’s Maya rulers and replaced them with a Teotihuacan puppet government. It also reveals how hard those foreign rulers fell from favor when Teotihuacan’s power finally waned centuries later.

Archaeologists don’t know what’s inside the altar, because they can’t excavate it without damaging the fragile painted panels. Credit: Ramirez et al. 2025

The painted altar

The altar stands in the courtyard of what was once a wealthy, influential person’s home in Tikal. At just over 1 meter tall, spanning nearly 2 meters in length and 1.3 meters wide, the altar is clearly the centerpiece of the limestone patio space.

It’s made of carved stone and earthen layers, covered with several smooth, fine plaster coatings. Murals adorn recessed panels on all four sides. In red, orange, yellow, and black, the paintings all depict the face of a person in an elaborate feathered headdress, but each is slightly different. All four versions of the face stare straight at the viewer through almond-shaped eyes. The figure wears the kind of facial piercings that would have marked a person of very high rank in Teotihuacan: a nose bar and spool-shaped ear jewelry (picture a fancy ancient version of modern earlobe plugs).

Proyecto Arqueológico del Sur de Tikal archaeologist Edwin Ramirez and his colleagues say the faces on the altar look uncannily like a deity who often shows up in artwork from central Mexico, in the area around Teotihuacan. Archaeologists have nicknamed this deity the Storm God, since they haven’t yet found any trace of its name. It’s a distinctly Teotihuacan-style piece of art, from the architecture of the altar to the style and color of the images and even the techniques used in painting them. Yet it sits in the heart of Tikal, a Maya city.

A pre-Columbian coup d’etat

Tikal was one of the biggest and most important cities of the Maya civilization. Founded in 850 BCE, it chugged along for centuries as a small backwater until its sudden rise to wealth and prominence around 100 CE. Lidar surveys of Guatemala have revealed Tikal’s links with other Maya cities, like Homul. And Tikal also traded with the city of Teotihuacan, more than 1,000 kilometers to the west, in what’s now Mexico.

“These powers of central Mexico reached into the Maya world because they saw it as a place of extraordinary wealth, of special feathers from tropical birds, jade, and chocolate,” says Brown University archaeologist Stephen Houston, a co-author of the recent study, in a statement. “As far as Teotihuacan was concerned, it was the land of milk and honey.”

Trade with Teotihuacan brought wealth to Tikal, but the Maya city seems to have attracted too much attention from its more powerful neighbor. A carved stone unearthed in Tikal in the 1960s describes how Teotihuacan swooped in around 378 CE to oust Tikal’s king and replace him with a puppet ruler. Spanish-language sources call this coup d’etat the Entrada.

The stone is carved in the style of Teotihuacan, but it’s also covered with Maya hieroglyphs, which tell the tale of the conquest. After the Entrada, there are traces of Teotihuacan’s presence all over Tikal, from royal burials in a necropolis to distinctly Mexican architecture mixed with Maya elements in a complex of residential and ceremonial buildings near the heart of the city.

And the newly unearthed altar seems to have been built shortly after the Entrada, based on radiocarbon dates from nearby graves in the courtyard and from material used to ritually bury the altar after its abandonment (more on that below).

Ramirez and his colleagues write that the altar is “likely evidence of the direct presence of Teotihuacan at Tikal as part of a foreign enclave that coincided with the historic Entrada.”

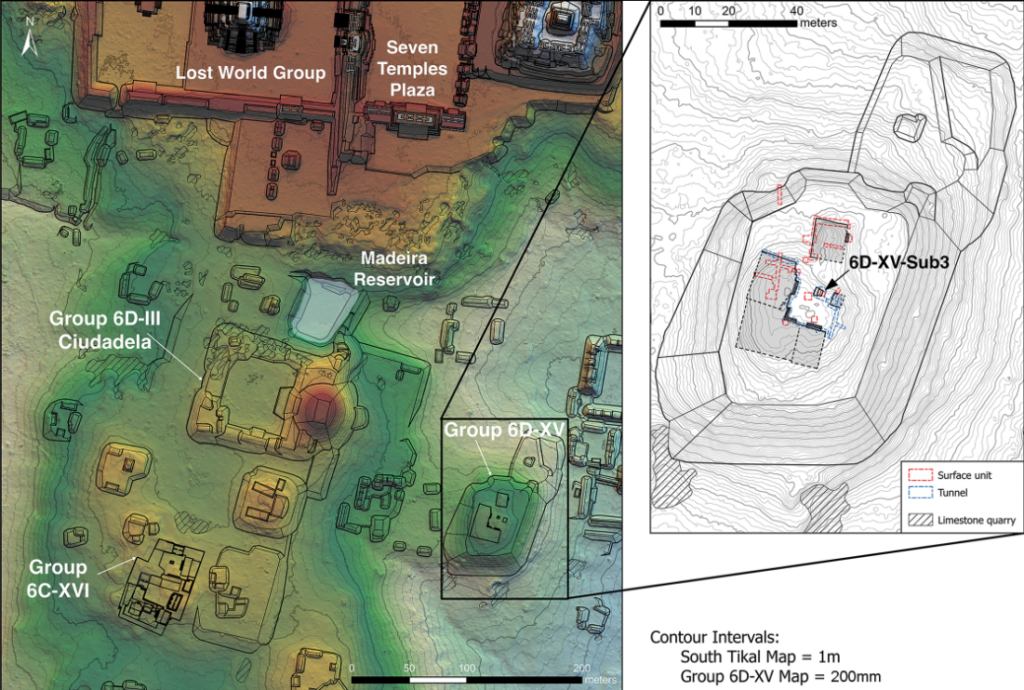

This map shows the courtyard in relation to other major structures in Tikal. Credit: T.G. Garrison and H. Hurst

A wealthy household’s ritual courtyard

The buildings surrounding the courtyard would have been a residential compound for wealthy elites in the city; it’s not far from the city’s center with its temples and huge public plazas. Residents had used the courtyard as a private family ceremonial space for decades or even a couple of centuries before its owners installed the altar. And Ramirez and his colleagues say it’s no coincidence that archaeologists have found many such courtyards in Teotihuacan, which people also used as a space for household ceremonies like burials and offerings to the gods.

“What the altar confirms is that wealthy leaders from Teotihuacan came to Tikal and created replicas of ritual facilities that would have existed in their home city. It shows Teotihuacan left a heavy imprint there,” says Houston.

And in the Maya world, as in the world of Teotihuacan, ceremonial spaces usually come with skeletons included.

Ramirez and his colleagues unearthed the grave of an adult buried beneath the patio, in a tomb with limestone walls and a stucco floor. Nearby, a child had been buried in a seated position—something rare in Tikal but very common in Teotihuacan. The child’s burial radiocarbon-dated to decades before the Entrada, between 205 and 350 CE. It looks like someone buried both of these people beneath the floor of the courtyard of their residential compound not long after they moved in; it’s a good bet that they were members of the family who once lived here, but archaeologists don’t know for sure. These kinds of burials would have been exactly the sort of household ritual the courtyard was meant for.

Teotihuacan’s enclave in Maya Tikal

Sometime later—between 380 and 540 CE, based on radiocarbon dating—the people living in the compound buried the courtyard beneath a layer of dirt and rubble, laid a new floor over it, and essentially started over. This is when Ramirez and his colleagues say someone built and painted the altar.

It’s also when someone buried three babies in the courtyard, each near a corner of the altar (the fourth corner has a jar that probably once contained an offering, but no bones). Each burial required breaking the stone floor, placing the tiny remains underneath, and then filling in the hole with crushed limestone. That’s not the way most people in Tikal would have buried an infant, but it’s exactly how archaeologists have found several buried in very similar courtyards in faraway Teotihuacan.

In other words, the people who lived in this compound and used this courtyard and painted altar were probably from Teotihuacan or raised in a Teotihuacan enclave in the southern sector of Tikal. The compound is practically in the shadow of a replica of Teotihuacan’s Feathered Serpent Pyramid and its walled plaza, where archaeologists unearthed Teotihuacan-style incense burners made from local materials.

This rendering shows what the altar might have looked like in its heyday. Credit: Heather Hurst

The end of an era

Sometime between 550 CE and 654 CE, based on radiocarbon dating, the foreign enclave in Tikal closed up shop. That’s around the time distant Teotihuacan’s power was starting to collapse. But it wasn’t enough to just leave; important buildings had to be ritually “killed” and buried. That meant burning the area around the altar, but it also meant that people buried the altar, the courtyard, the compound, and most of southern Tikal’s Teotihuacan enclave beneath several meters of dirt and rubble.

Whoever did the burying went to the trouble of making the whole thing look like a natural hill. Ramirez and his colleagues say that’s unusual, because typically once a building had been ritually killed and abandoned, something new would be built atop the remains.

“The Maya regularly buried buildings and rebuilt on top of them,” Brown University archaeologist Andrew Scherer, a co-author of the recent study, said in a statement. “But here, they buried the altar and surrounding buildings and just left them, even though this would have been prime real estate centuries later. They treated it almost like a memorial or a radioactive zone. It probably spoke to the complicated feelings they had about Teotihuacan.”

Antiquity, 2017. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.3 (About DOIs).

Painted altar in Maya city of Tikal reveals aftermath of ancient coup Read More »