Complexity physics finds crucial tipping points in chess games

For his analysis, Barthelemy chose to represent chess as a decision tree in which each “branch” leads to a win, loss, or draw. Players face the challenge of finding the best move amid all this complexity, particularly midgame, in order to steer gameplay into favorable branches. That’s where those crucial tipping points come into play. Such positions are inherently unstable, which is why even a small mistake can have a dramatic influence on a match’s trajectory.

A case of combinatorial complexity

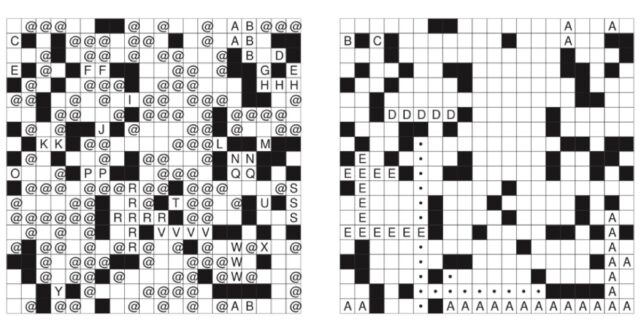

Barthelemy has re-imagined a chess match as a network of forces in which pieces act as the network’s nodes, and the ways they interact represent the edges, using an interaction graph to capture how different pieces attack and defend one another. The most important chess pieces are those that interact with many other pieces in a given match, which he calculated by measuring how frequently a node lies on the shortest path between all the node pairs in the network (its “betweenness centrality”).

He also calculated so-called “fragility scores,” which indicate how easy it is to remove those critical chess pieces from the board. And he was able to apply this analysis to more than 20,000 actual chess matches played by the world’s top players over the last 200 years.

Barthelemy found that his metric could indeed identify tipping points in specific matches. Furthermore, when he averaged his analysis over a large number of games, an unexpected universal pattern emerged. “We observe a surprising universality: the average fragility score is the same for all players and for all openings,” Barthelemy writes. And in famous chess matches, “the maximum fragility often coincides with pivotal moments, characterized by brilliant moves that decisively shift the balance of the game.”

Specifically, fragility scores start to increase about eight moves before the critical tipping point position occurs and stay high for some 15 moves after that. “These results suggest that positional fragility follows a common trajectory, with tension peaking in the middle game and dissipating toward the endgame,” he writes. “This analysis highlights the complex dynamics of chess, where the interaction between attack and defense shapes the game’s overall structure.”

Physical Review E, 2025. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.00.004300 (About DOIs).

Complexity physics finds crucial tipping points in chess games Read More »