NEPA, Permitting and Energy Roundup #2

It’s been about a year since the last one of these. Given the long cycle, I have done my best to check for changes but things may have changed on any given topic by the time you read this.

NEPA is a constant thorn in the side of anyone attempting to do anything.

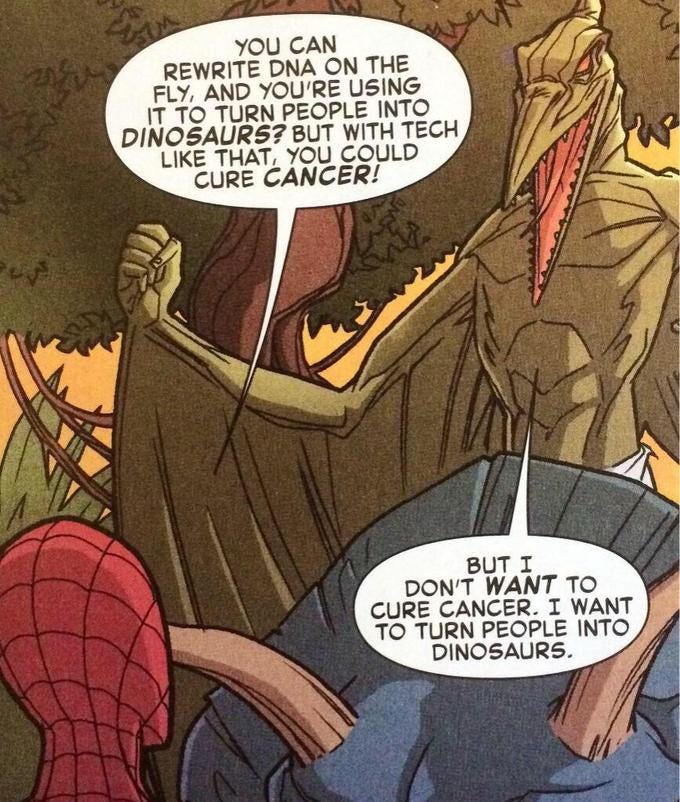

A certain kind of person responds with: “Good.”

That kind of person does not want humans to do physical things in the world.

-

They like the world as it is, or as it used to be.

-

They do not want humans messing with it further.

-

They often also think humans are bad, and should stop existing entirely.

-

Or believe humans deserve to suffer or do penance.

-

Or do not trust people to make good decisions and safeguard what matters.

-

To them: If humans want to do something to the physical world?

-

That intention is highly suspicious.

-

We probably should not let them do that.

This is in sharp contrast with the type of person who:

-

Cares about the environment.

-

Who wants good things rather than bad to happen to people.

-

Who wants the Earth not to boil and the air to be clean and so on.

That person notices that NEPA long ago started doing more harm than good.

The central problem lies is the core structure.

NEPA is based on following endlessly expanding procedural requirements. NEPA does not ask whether costs exceed benefits, or whether something is a good idea.

It only asks about whether procedure was followed sufficiently, or whether blame can be identified somewhere.

Is to never go full NEPA.

Instead, one of Balsa’s central policy goals is an entire reimagining of NEPA.

The proposal is to replace NEPA’s procedural requirement with (when necessary) an analysis of costs and benefits, followed by a vote of stakeholders on whether to proceed. Ask the right question, whether the project is worthwhile, not the wrong question of what paperwork is in order.

This post is not about laying out that procedure. This post is mostly about telling various Tales From the NEPA. It is also telling tales of energy generation from around the world, including places that do not share our full madness.

Versions and components of this post have been in my drafts for a long time, so not all of them will be as recent as is common here.

That was the plan, but the vibes have changed, and NEPA is pretty clearly a large net negative for climate change, which has to win in a fight at this point over the local concerns it protects. There’s a new plan.

Kill it. Repeal NEPA. Full stop.

Emmett Shear: Previously I believed that there was probably enough protection offered by NEPA / CEQA that it offset the damage. At this point, it’s pretty clear we should simply repeal it and figure out if we need to replace anything later.

Repeal NEPA.

Eli Dourado: NEPA is the most harmful law in the United States and must be repealed. In addition to causing forest fires and miring Starbase in litigation, it results in delays and endless litigation for any project that the federal government touches. It should be target #1 for DOGE.

Sadly this is not yet within the Overton window of relevant Congressional staff. We need to make this happen.

The problem is DOGE is working via cutting off payments, which doesn’t let you hit NEPA. But if you want to strike a blow that matters? This is it.

Thomas Hochman: Trump has revoked Carter’s 1977 EO – the one that empowered CEQ to issue binding NEPA regulations.

This could dramatically reshape how federal agencies conduct NEPA reviews. In the post-Marin Audobon landscape, this is a HUGE deal!

…

Let’s walk through a few of the specifics.

CEQ will formally propose repealing the existing NEPA regulations that have guided agencies since the late 1970s.

This is major: those regs currently supply the standard NEPA procedures (e.g., EIS format, “major federal action,” significance criteria, scoping, etc.).

Rescinding them will leave agencies free to adopt leaner, agency-specific processes—or rely on new guidance.

CEQ will lead a “working group” composed of representatives from various agencies.

This group’s job is to develop or revise each agency’s own NEPA procedures so that they’re consistent with the new (post-rescission) approach.

As I wrote in Green Tape, establishing this internal guidance at the agency level will be crucial.

And finally: general permits and permits-by-rule!!!

Eli Dourado: NEPA is still there but CEQ’s authority to issue regs is gone (and was already under dispute in the courts). NEPA the statute still applies.

Cremieux: Some pretty major components of permitting reform on day one might be the biggest news in the day one EOs.

There’s trillions in value in these EOs.

I am delighted.

You love to see it. This day one move gave me a lot of hope things would go well, alas other things happened that were less good for my hopes.

As with everything Trump Administration, we will see what actually happens once the lawyers get involved. This is not an area where ‘ignore the law and simply do things’ seems likely to work out. Some of it will stick, but how much?

Yay nuclear deregulation, yes obviously, Alex Tabarrok opens with ‘yes, I know how that sounds’ but actually it sounds great if you’re familiar with the current regulations. I do see why one would pause before going to the level of ‘treat small modular reactors like x-ray machines,’ I’d want to see the safety case and all that, but probably.

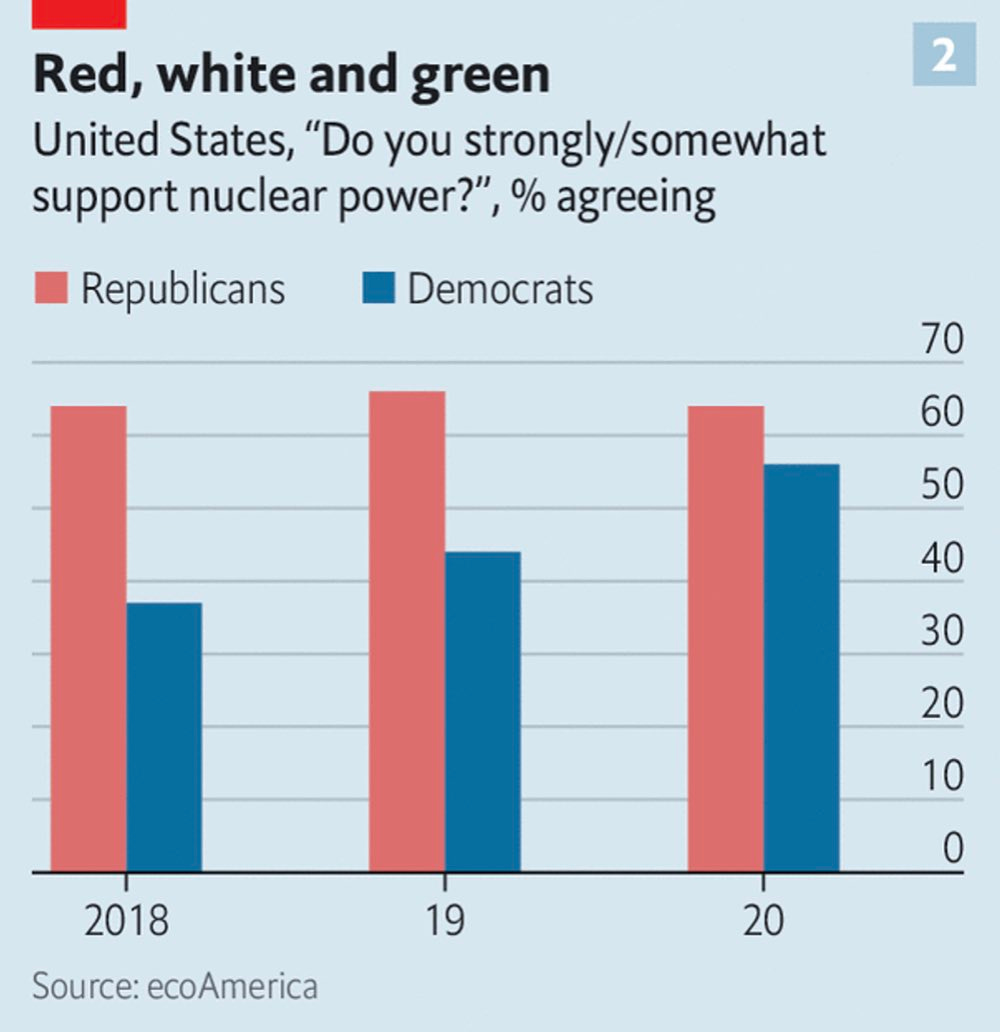

Nuclear is making an attempted comeback, now that AI and trying the alternative of doing nothing has awoken everyone to the idea that this will be a good idea.

Alexander Kaufman: The Senate voted nearly unanimously (88-2) to pass major legislation designed to reverse the American nuclear industry’s decades-long decline and launch a reactor-building spree to meet surging demand for green electricity at home and to catch up with booming rivals overseas.

The bill slashes the fees the Nuclear Regulatory Commission charges developers, speeds up the process for licensing new reactors and hiring key staff, and directs the agency to work with foreign regulators to open doors for U.S. exports.

The NRC is also tasked with rewriting its mission statement to avoid unnecessarily limiting the “benefits of nuclear energy technology to society,” essentially reinterpreting its raison d’être to include protecting the public against the dangers of not using atomic power in addition to whatever safety threat reactors themselves pose.

There is a lot of big talk about how much this will change the rules on nuclear power regulation. As usual I remain skeptical of big impacts, but it would not take much to reach a tipping point. As the same post notes when discussing the reactors in Georgia, once you relearn what you are doing things get a lot better and cheaper.

That pair of reactors, which just came online last month at the Alvin W. Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in Georgia, cost more than $30 billion. As the expenses mounted, other projects to build the same kind of reactor elsewhere in the country were canceled.

The timing could hardly have been worse. After completing the first reactor, the second one cost far less and came online faster. But the disastrous launch dissuaded any other utilities from investing in a third reactor, which economists say would take even less time and money now that the supply chains, design and workforce are established.

After seeing the results, the secretary of energy called for ‘hundreds’ more large nuclear reactions, two hundred by 2050.

NextEra looking to restart a nuclear plant in Iowa that closed in 2020.

Ontario eyeing a new nuclear plant near Port Hope, 8-10 GWs.

It seems the world is a mix of people who shut down nuclear power out of spite and mood affiliation and intuitions that nuclear is dangerous or harmful when it is orders of magnitudes safer and fully green, versus those who realize we should be desperate to build more.

Matthew Yglesias: The all-time energy champ

Matthew Yglesias: The Fukushima incident was deadly not because anyone died in the accident but because the post-Fukushima nuclear shutdown caused more Japanese people to freeze to death to conserve energy.

Dean Ball is excited by the bill, including its prize for next-gen nuclear tech and the potential momentum for future action.

There is a long way to go. It seems we do things like this? And the lifetime for nuclear power plants has nothing to do with their physical capabilities or risks?

Alec Stapp: Apparently we have been arbitrarily limiting licenses for nuclear power reactors to 40 years because of… “antitrust considerations”??

Nuclear Regulatory Commission: The Atomic Energy Act authorizes the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to issue licenses for commercial power reactors to operate for up to 40 years. These licenses can be renewed for an additional 20 years at a time. The period after the initial licensing terris known as the period of extended operation. Economic and antitrust considerations, not limitations of nuclear technology, determined the original 40-year term for reactor licenses. However, because of this selected time period, some systems, structures, and components may have been engineered on the basis of an expected 40-year service life.

Or how many nuclear engineers does it take to change a light bulb? $50k worth.

How much for a $200 panel meter in a control room? Trick question, it’s $20k.

And yet nuclear is still at least close to cost competitive.

The Senate also previously forced Biden to drop attempt to renominate Jeff Baran to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), the the basis of Baran being starkly opposed to the concept of building nuclear power plants.

Why has Biden effectively opposed nuclear power? My model is that it is the same reason he is effectively opposing power transmission and green energy infrastructure. Biden thinks throwing money and rhetoric at problems makes solutions happen. He does not understand, even in his best moments, that throwing up or not removing barriers to doing things stops those things from happening even when that was not your intention.

Thus, he can also do things like offer $1.5 billion in conditional commitments to support recommissioning a Michigan nuclear power plant, because he understands that more nuclear power plants would be a good thing. And he can say things like ‘White House to support new nuclear power plants in the U.S.’ That does not have to cause him to, in general, do the things that cause there to be more nuclear power plants. Because he cannot understand that those are things like ‘appoint people to the NRC that might ever want to approve a new nuclear power plant in practice.’ Luckily, it sounds like the new bill does indeed help.

Small modular nuclear reactor (SMR) planned for Idaho, called most advanced in the nation, was cancelled in January after customers could not be found to buy the electricity. Only a few months later, everyone is scrambling for more electricity to run their data centers. It seems like if you build it, Microsoft or Google or Amazon will be happy to plop a data center next to that shiny new reactor, no? And certainly plenty of other places would welcome one. So odd that this got slated first for Idaho.

Alberta signs deal to jointly assess the development and deployment of SMRs. One SMR is to be built in Ontario by end of 2028, to be online in 2029.

Slovakia to build a new nuclear reactor. Also talk of increased capacity in France, Italy, Britain, Japan, Canada, Poland and The Netherlands in the thread, from May. From December 2023: Poland authorizes 24 new small nuclear plants.

Philippines are considering nuclear as well.

Support for Nuclear in Australia has increased dramatically to 61%-37%.

Claim that the shutdown of nuclear power in Germany was even more corrupt than we realized, with the Green Party altering expert conclusions to stop a reconsideration. The claims have been denied.

Unfortunately, we are allowing an agreement whereby Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) will not be allowed to bid on new nuclear projects in Western countries, due to an IP issue with Westinghouse, on top of them paying royalties for any Asian projects that move forward. The good news is that if Westinghouse wins the projects, KHNP and KEPCO are prime sub-contractors anyway, so it is unclear this is that much of a functional

India’s energy mix is rapidly improving.

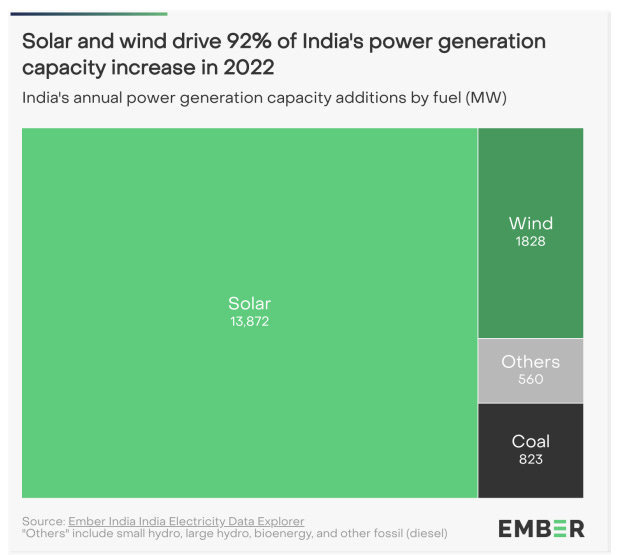

John Raymond Hanger: Good morning with good news: Solar and wind were 92% of India’s generation additions in 2022. It deployed as much solar in 2022 as the UK has ever built. Coal also was down 78%.

India’s large wind & solar additions are vital climate action. Wonderful!

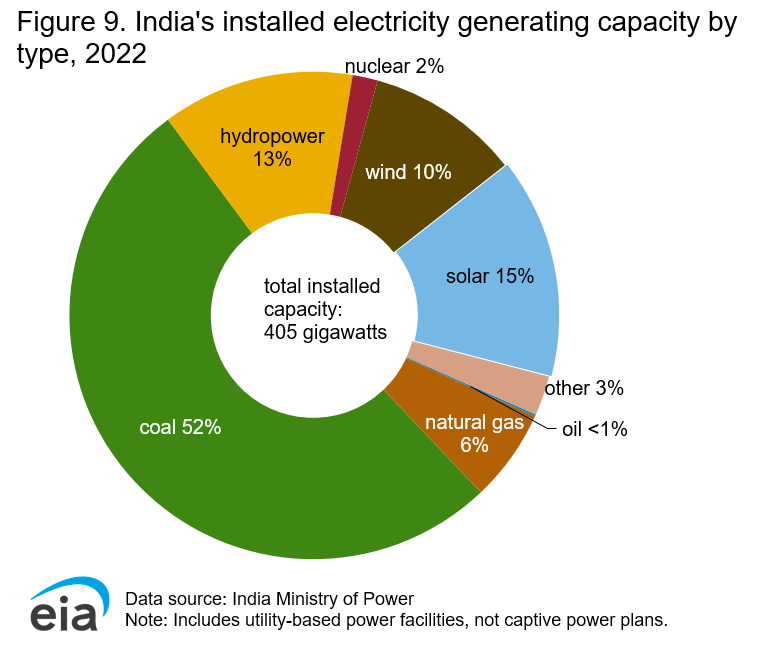

David Bryan: Confusingly written. Coal in India is at 55%. Wind is at 10% & solar is at 12% – sometimes more, sometimes less.

A Zaugurz: mmmkay “India has an estimated 65.3 GW of proposed, on-grid coal capacity under active development: 30.4 GW under construction and 34.9 GW in pre-construction”

Stocks are different from flows are different from changes in flow.

India was still adding more coal capacity even as of December. But almost all of their new capacity was Solar and Wind, and they are clearly turning the corner on new additions. One still has to then make emissions go down, and then make net emissions drop below zero. One step at a time.

Also, 15% of the installed base is already not bad at all. Renewables are a big deal. A shame nuclear is only 2%.

Khavda in India, now the world’s largest renewable energy park using a combination of solar and wind energy.

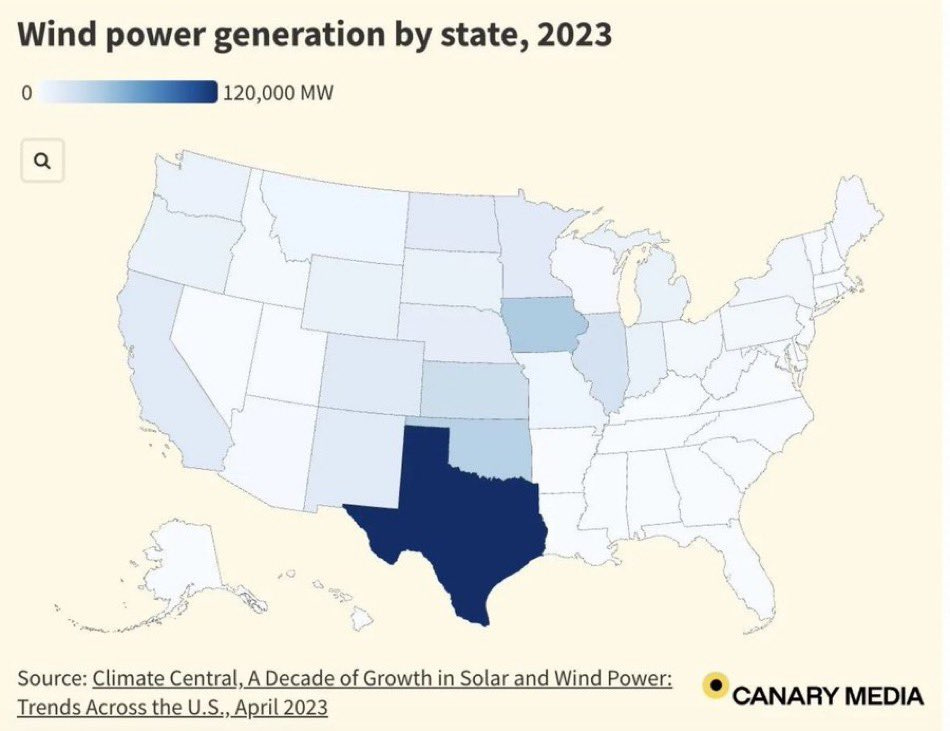

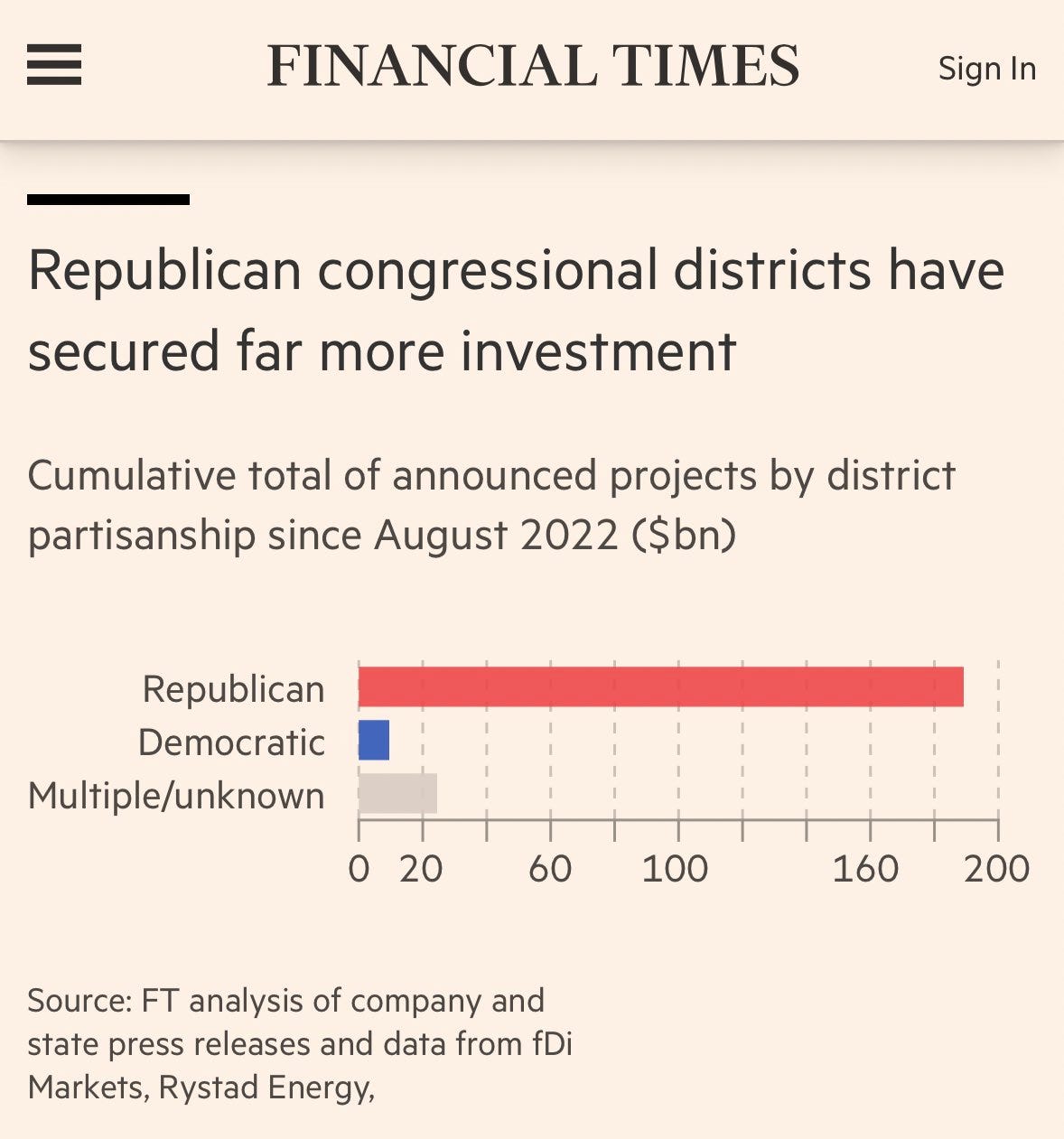

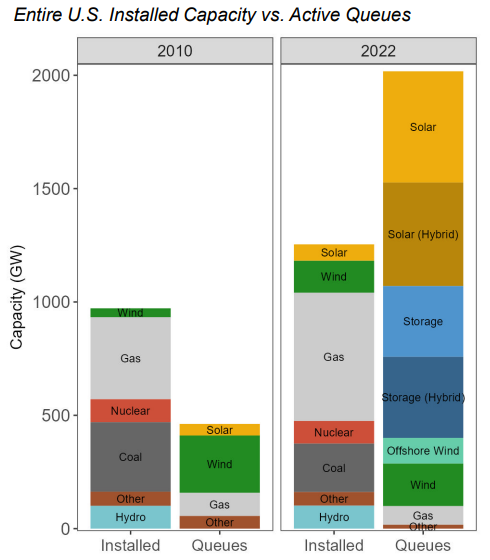

Back in America, who is actually building the most solar?

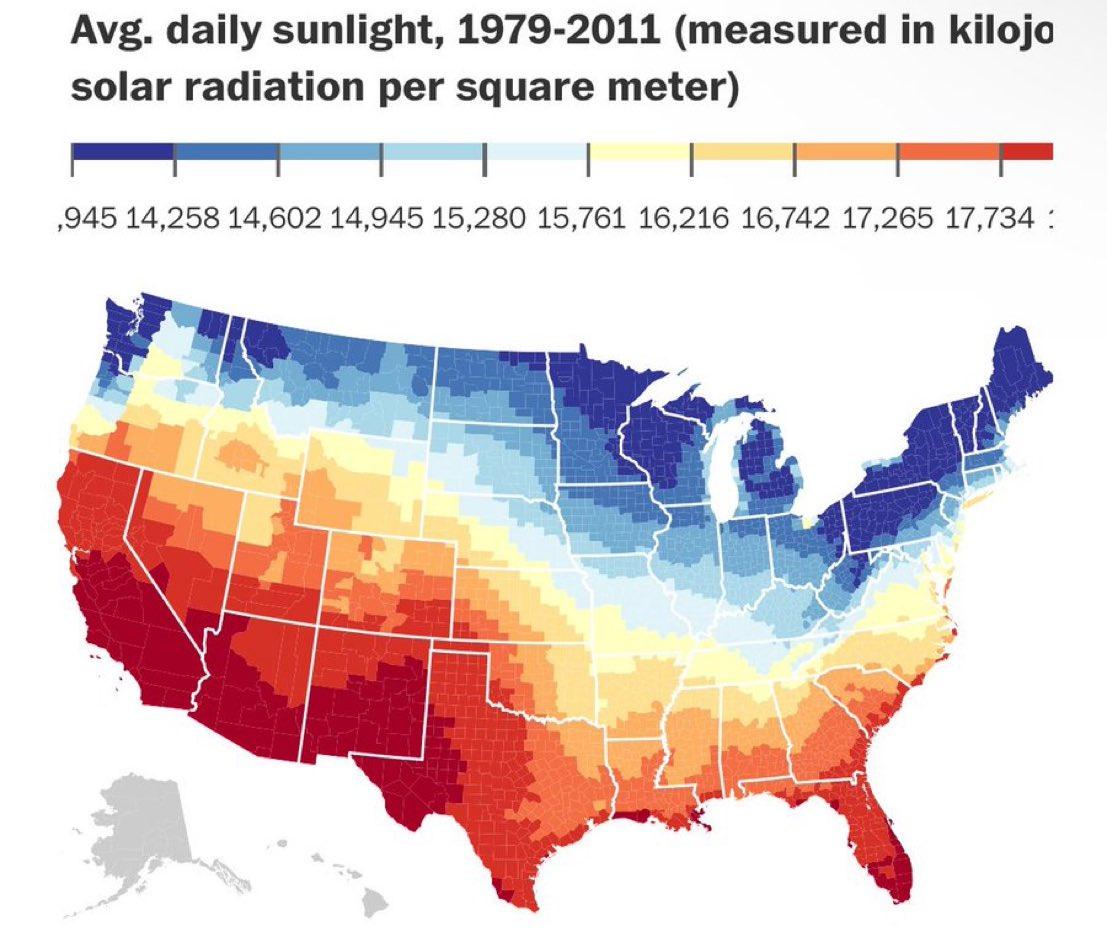

Why, Texas, of course. California talks a good game, but what matters most (aside from sunlight where California has the edge) is not getting in the way.

EIAGov: More than half of the new utility-scale solar capacity scheduled to come online in 2024 is planned for three states: Texas (35%), California (10%) and Florida (6%).

Alec Stapp: Blue states talk a big game on clean energy goals while Texas just goes and builds it.

Texas is building grid-scale solar at a much faster rate than California.

Can’t be due to regulations — must be because CA is a small state with little sunshine 🙃

The numbers mean that despite being the state with at least the third most sunlight after Arizona and New Mexico, California is bringing online solar per capita than the nation overall.

If you want to install home solar, it is going to get expensive in the sense that the cost of the panels themselves is now less than 10% of your all-in price.

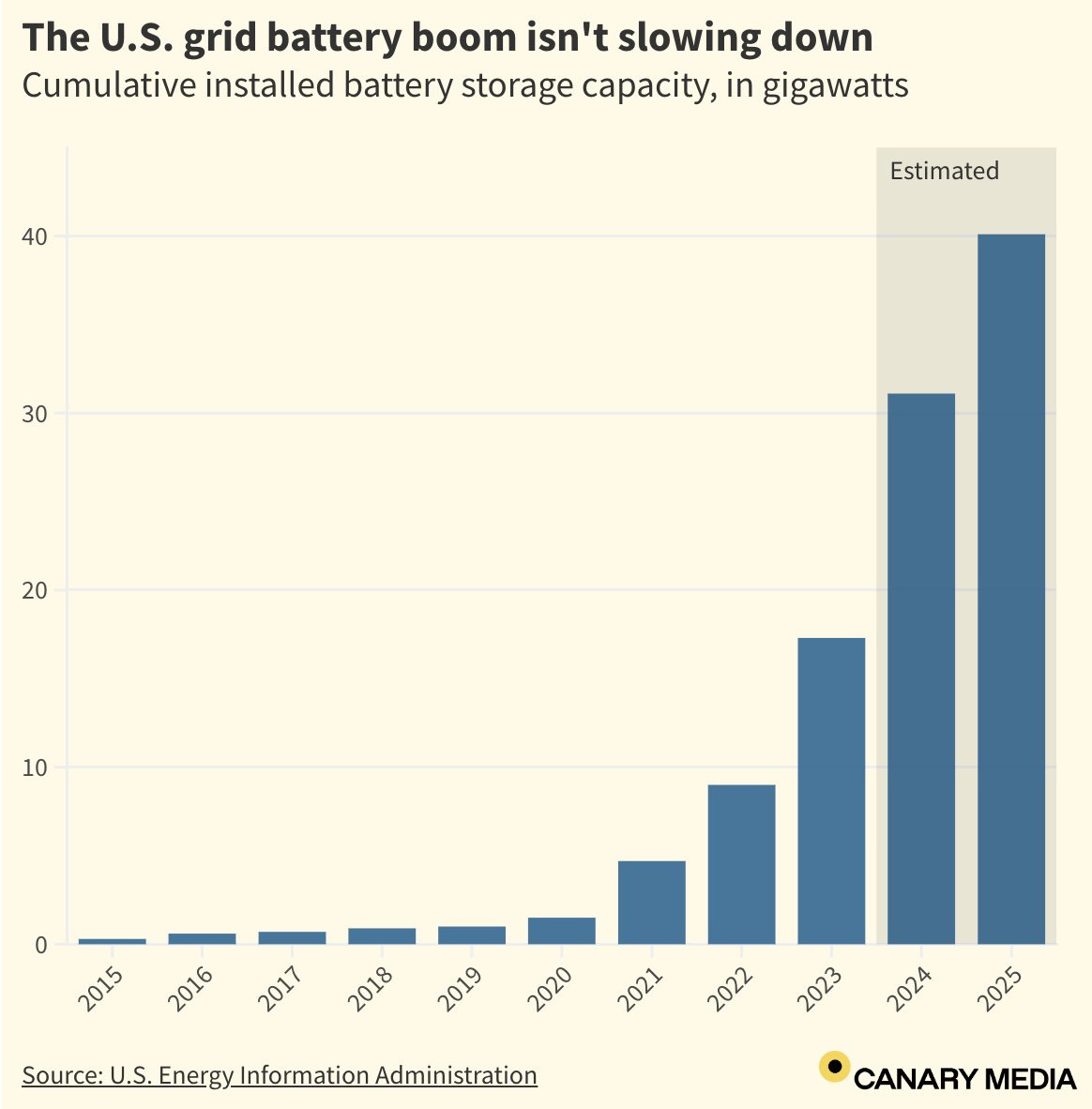

This is a great start, but still a drop in the bucket, as I understand it, compared to what we will need if we intend to largely rely on solar and wind in the future.

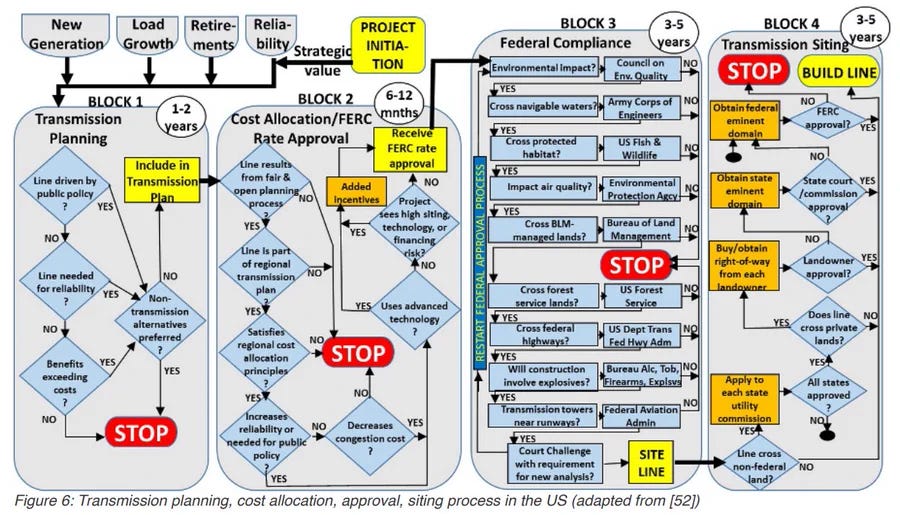

One enemy of transmission lines and other grid capabilities are NIMBYs who block projects. This includes the projects that never get proposed because of anticipation that they would then be blocked, or would require time and money to not be blocked.

Tyler Cowen reprints an anonymous email he got, that notes that there is also an incentive problem.

When you increase power transmission capacity, you make power fungible between areas. Which is good, unless you are in the power selling business, in which case this could mean more competition and less profit. By sticking to smaller local projects, you can both avoid scrutiny and mostly get the thing actually built, and also avoid competition.

That makes a lot of sense. It suggests we need to look at who is tasked with building new transmission lines, and who should be bearing the costs, including the need to struggle to make the plans and ensure they actually happen.

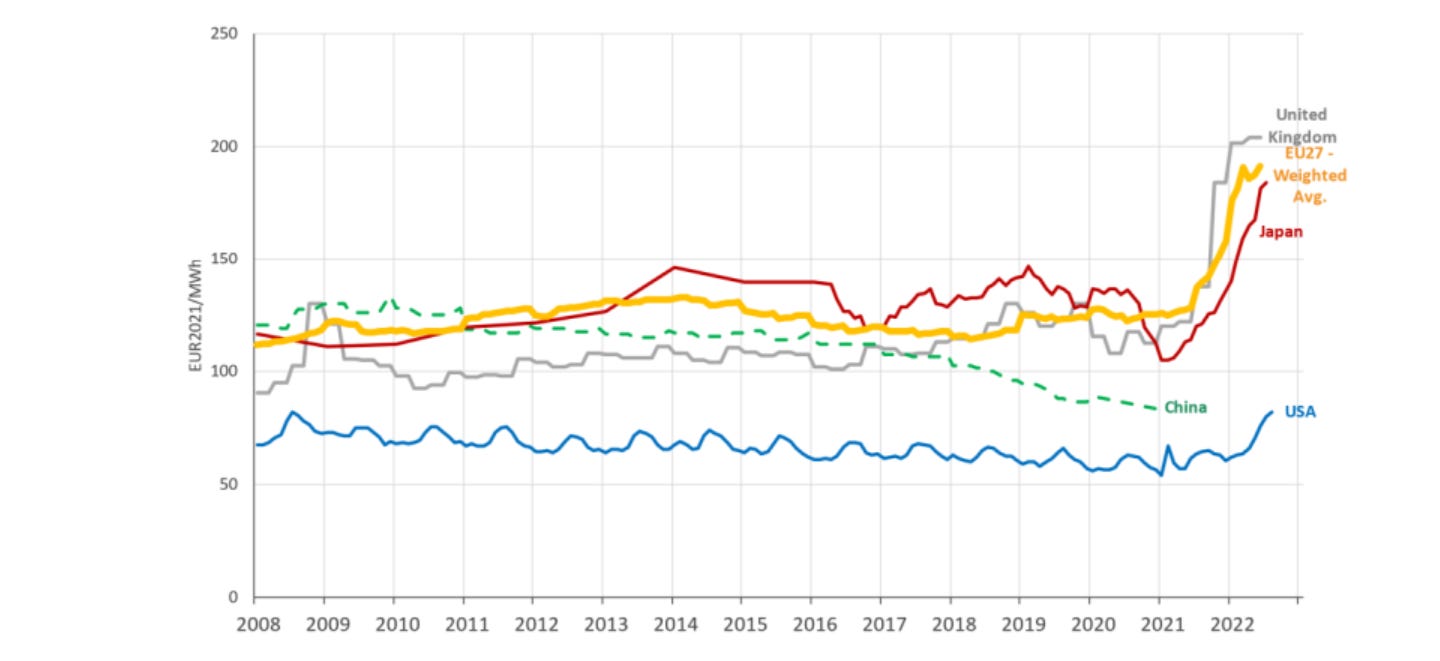

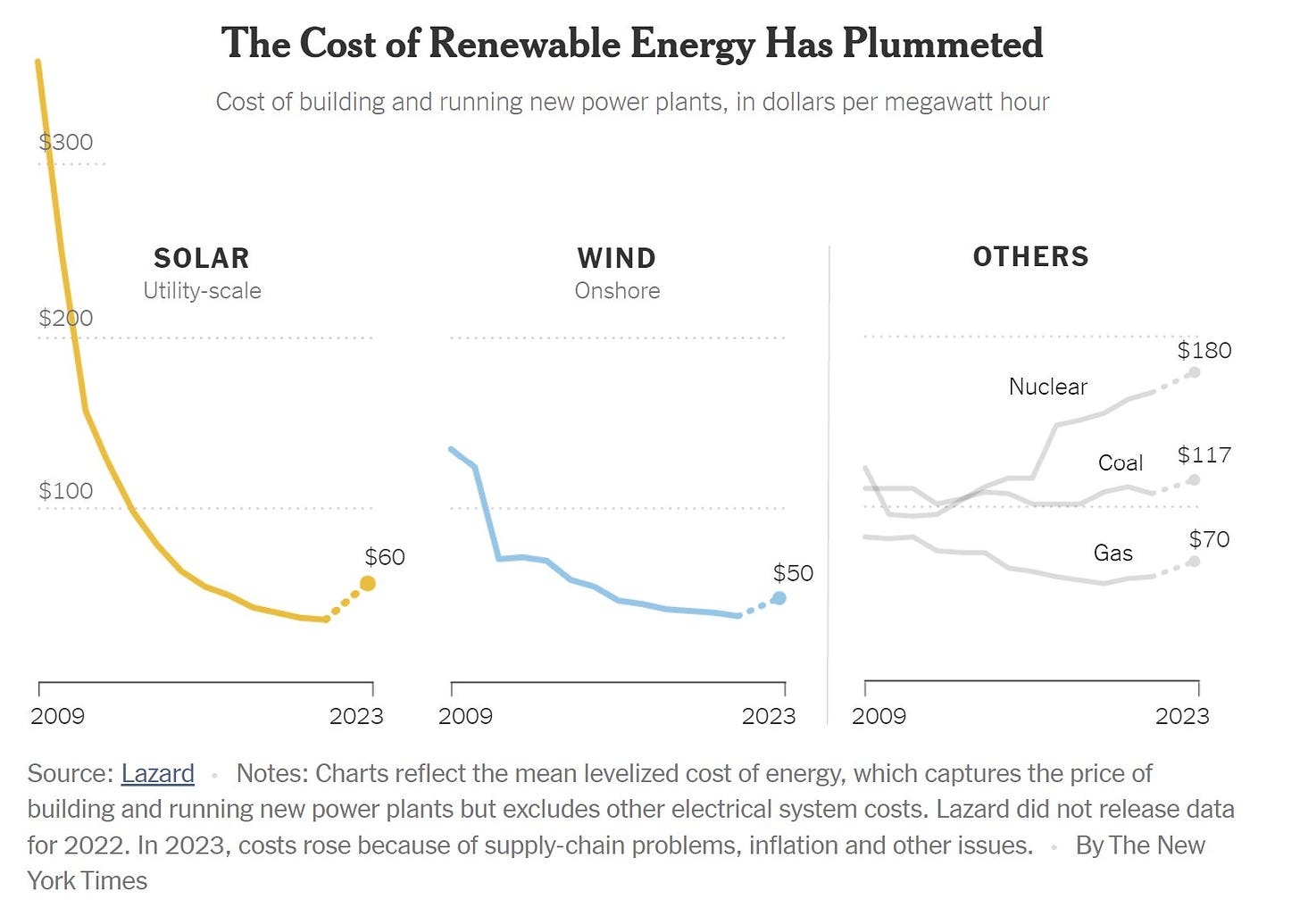

Why do we produce so little energy in America? Partly because it is so cheap.

Alex Tabarrok: The US has some of the lowest electricity prices in the world. Shown below are industrial retail electricity prices in EU27, USA, UK, China and Japan. Electricity is critical for AI compute, electric cars and more generally reducing carbon footprints. The US needs to build much more electricity infrastructure, by some estimates tripling or quadrupling production. That’s quite possible with deregulation and permitting reform. I am pleased to learn, moreover, that we are starting from a better base than I had imagined.

Amazing how much prices elsewhere have risen lately, and how timid has been everyone’s response.

Harvard was going to do something useful and run a geoengineering experiment. They cancelled it, because of course they did. And their justifications were, well…

James Temple (MIT Technology Review): Proponents of solar geoengineering research argue we should investigate the concept because it may significantly reduce the dangers of climate change. Further research could help scientists better understand the potential benefits, risks and tradeoffs between various approaches.

But critics argue that even studying the possibility of solar geoengineering eases the societal pressure to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Maxwell Tabarrok: The moral hazard argument against geoengineering is ridiculous. The central problem of climate change is that firms ignore the cost of carbon emissions.

Since these costs are already ignored, decreasing them will not change their actions, but it will save lives.

It is difficult to grasp how horrible this reasoning actually is. I can’t even. Imagine this principle extended to every other bad thing.

Yes, actually implementing such solutions comes with a lot of costs and dangers. That makes it seem like a good idea to learn now what those are via experiments? Better to find out now than to wait until the crisis gets sufficiently acute that people or nations get desperate?

The alternative hypothesis is that many people who claim to care about the climate crisis are remarkably uninterested in the average temperatures in the world not going up. We have a lot of evidence for this hypothesis.

Chris Elmendorf: A $650m project would:

– subtract 20 acres from wildlife refuge

– add 35 acres to same refuge

– connect 160 renewable energy projects to grid

Not with NEPA + local enviros standing in the way. Even after “years” of enviro study.

Kevin Stevens: An environmental group successfully blocked the last miles of a nearly complete 102 mile transmission line that would connect 160 renewable sites to the Midwest. Brutal.

I mean it’s completely insane that we would let 20 acres stop this at all, the cost/benefit is so obviously off the charts even purely for the environmental impacts alone. But also they are adding 35 other acres. At some point, you have to wonder why you are negotiating with people who are never willing to take any deal at all.

The answer is, you are forced to ‘negotiate,’ they pretend to do so back, you give them concessions like the above, and then they turn around and keep suing, with each step adding years of delay. The result is known as a ‘doom loop.’

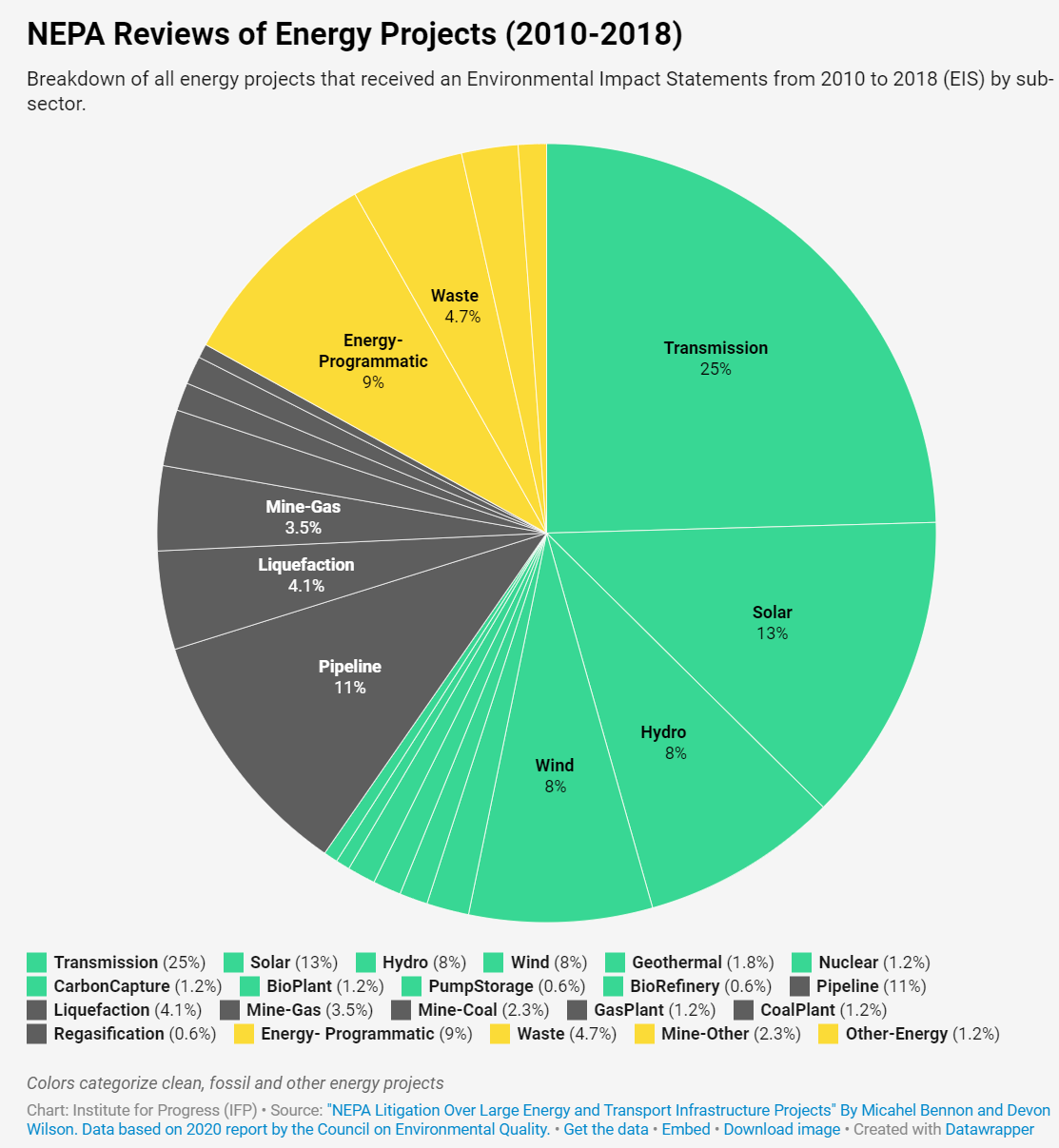

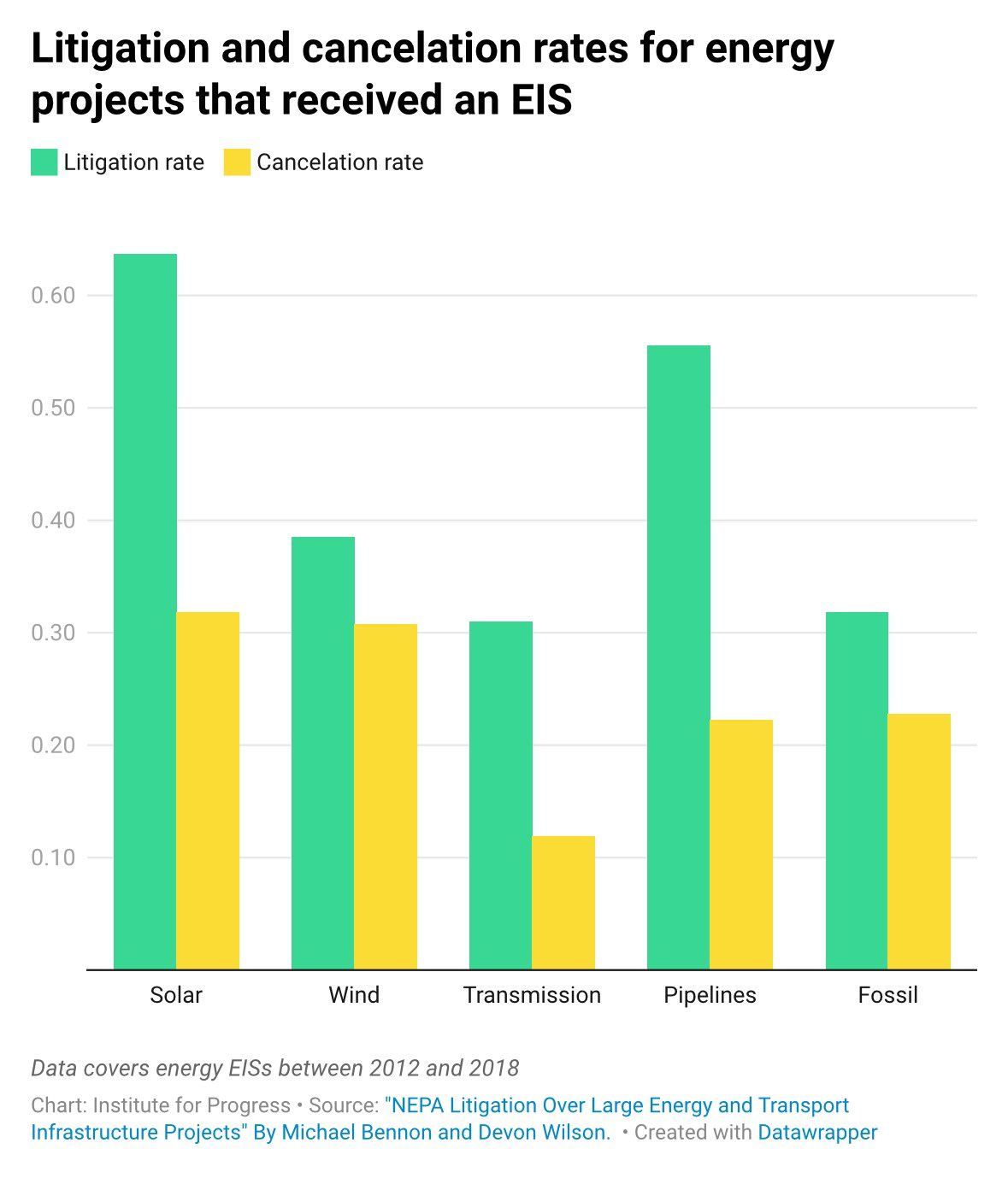

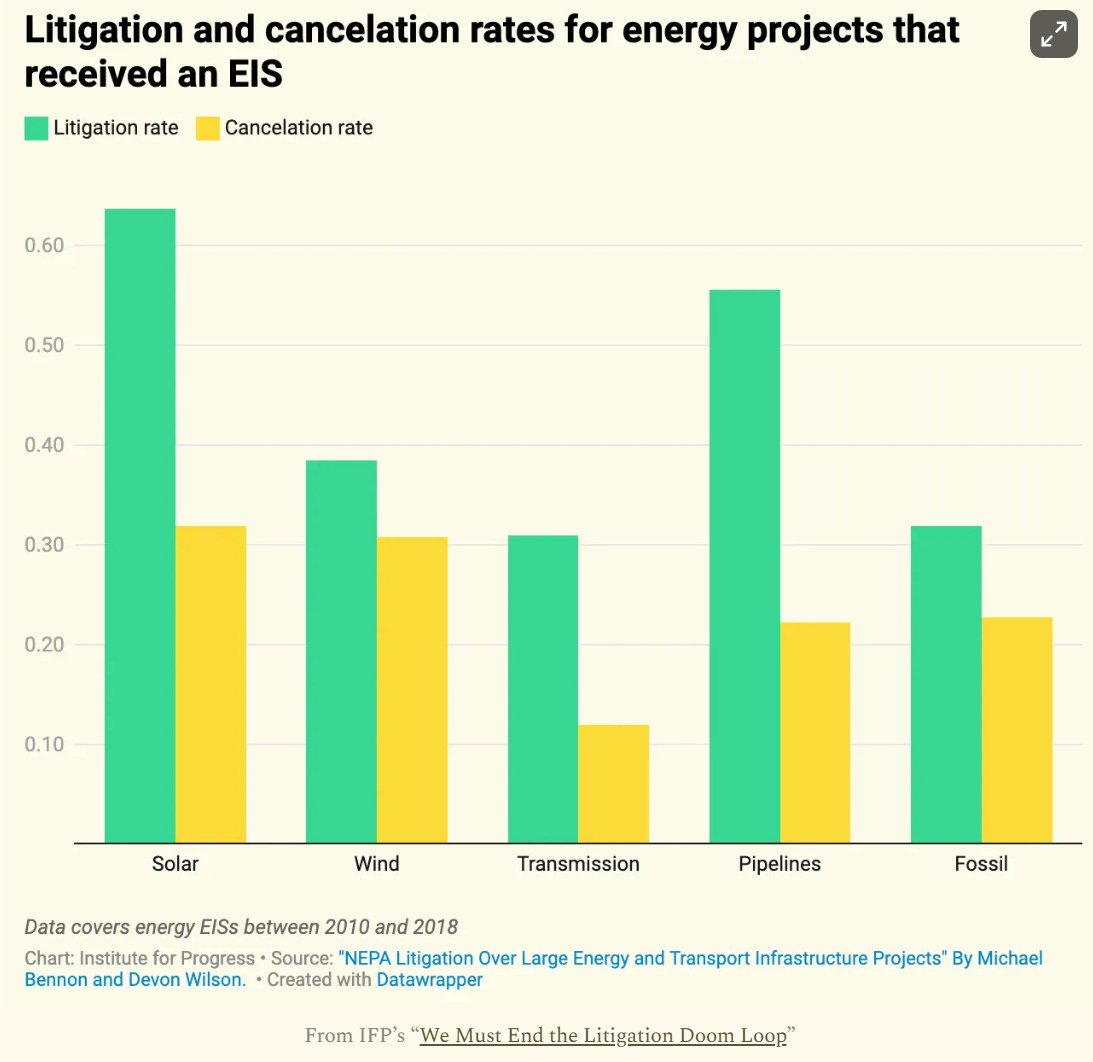

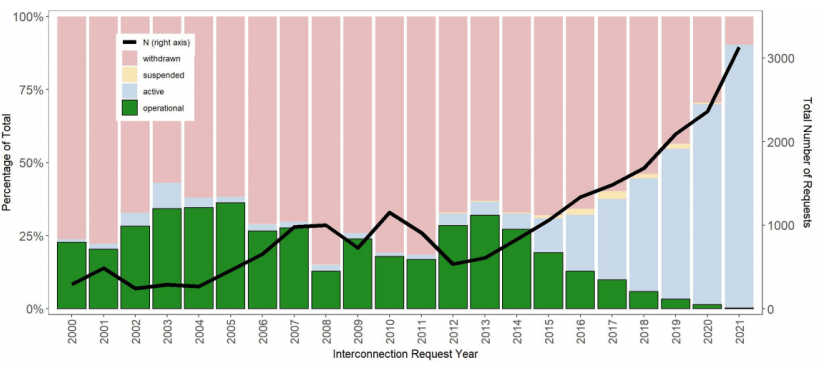

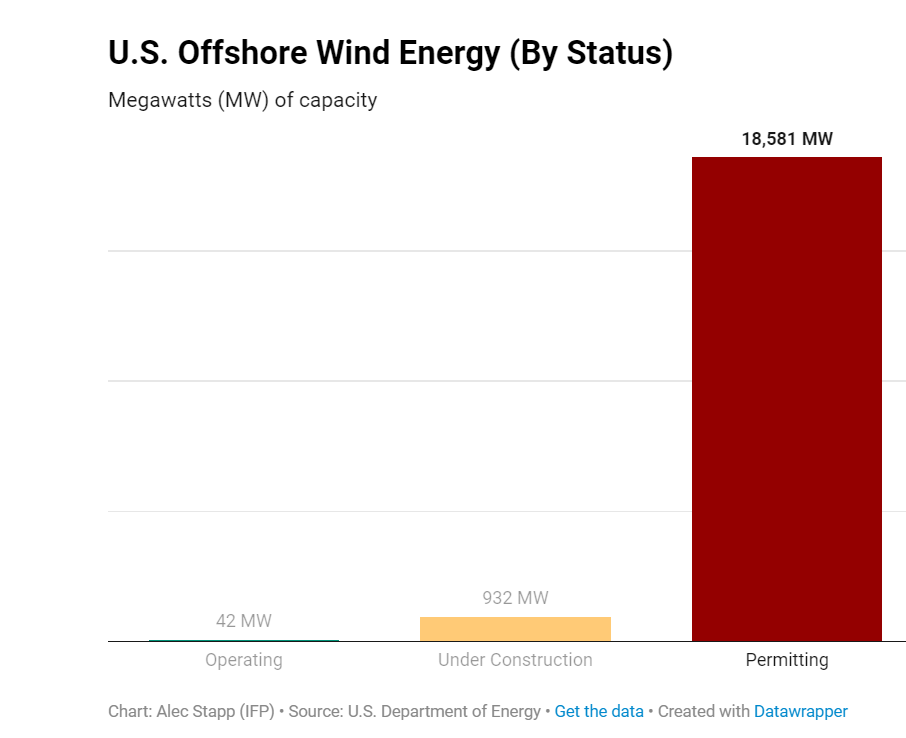

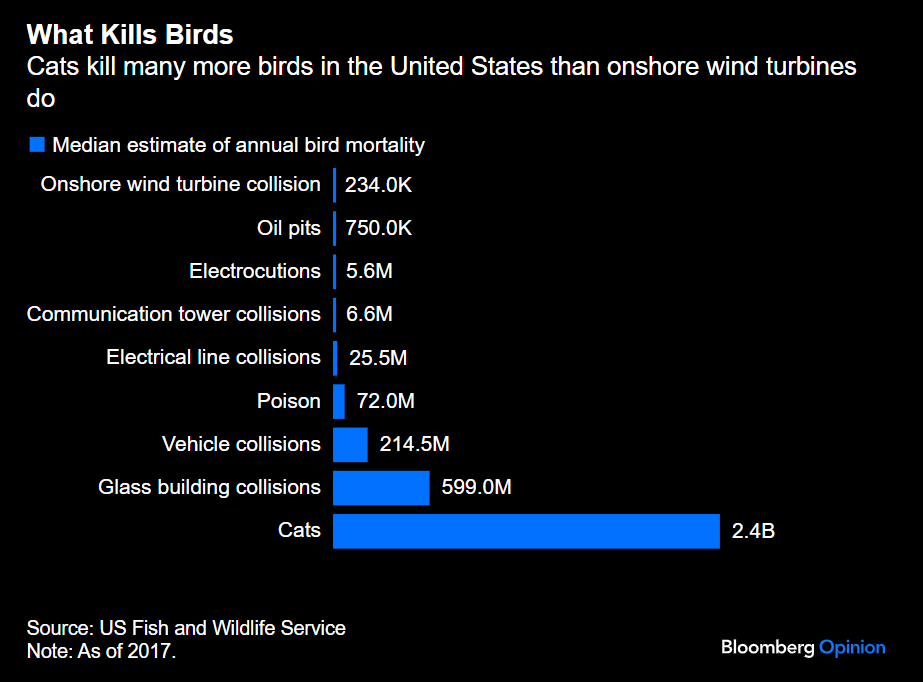

Clean energy projects are the very projects most likely to get stuck in the litigation doom loop. A recent Stanford study found that clean energy projects are disproportionately subject to the strictest level of review. These reviews are also litigated at higher rates — 62% of the projects currently pending the strictest review are clean energy projects. The best emissions modelers show that our emissions reductions goals are not possible without permitting reform.

That is why we’re proposing a time limit on injunctions. Under our proposal, after four years of litigation and review, courts could no longer prevent a project from beginning construction. This solution would pair nicely with the two-year deadlines imposed on agencies to finish review in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. If the courts believe more environmental review is necessary, they could order the government to perform it, but they could no longer paralyze new energy infrastructure construction.

This kills projects, and not the ones you want to kill. I am actually surprised the graph here lists rates that are this low.

If we are not going to do any other modifications, a time limit on court challenges seems like the very least we can do. My preferred solution is to change the structure entirely.

The good news is that some actions are exempt. But the exemptions are illustrative.

Thomas Hochman: Perhaps the funniest categorical exclusion under NEPA is the one that allows the Department of the Interior to make an arrest without filling out an environmental assessment.

Alec Stapp: When everything qualifies as a “major federal action” under NEPA, you get absurd outcomes like this where agencies have to waste time creating categorical exclusions for every little thing.

This is how state capacity withers and dies.

So in practice, what does NEPA look like?

Congestion Pricing in NYC was a case in point before Hochul betrayed us.

It looks like this, seriously, read how the UFT itself made its claims.

United Federation of Teachers: In our lawsuit, we assert that this program, scheduled to go into effect this spring, cannot be put in place without the completion of a thorough environmental impact statement that includes the potential effects of the plan on the city’s air quality.

In our lawsuit, we assert that this program, scheduled to go into effect this spring, cannot be put in place without the completion of a thorough environmental impact statement that includes the potential effects of the plan on the city’s air quality.

The current plan would not eliminate air and noise pollution or traffic, but would simply shift that pollution and traffic to the surrounding areas, particularly Staten Island, the Bronx, upper Manhattan and Northern New Jersey, causing greater environmental injustice in our city.

Emmett Shear: This NYC teacher’s union in suing to stop congestion pricing by using a claims that it will somehow have a negative impact on the environment when fewer people drive into the city. Truly extraordinary.

Joey Politano: “Teachers Union Sues NYC Over Congestion Pricing Proposal’s Lack of Thorough Environmental Review” would almost be too on the nose for an Onion headline about the problems with American transit & environmental policy, and yet here we are.

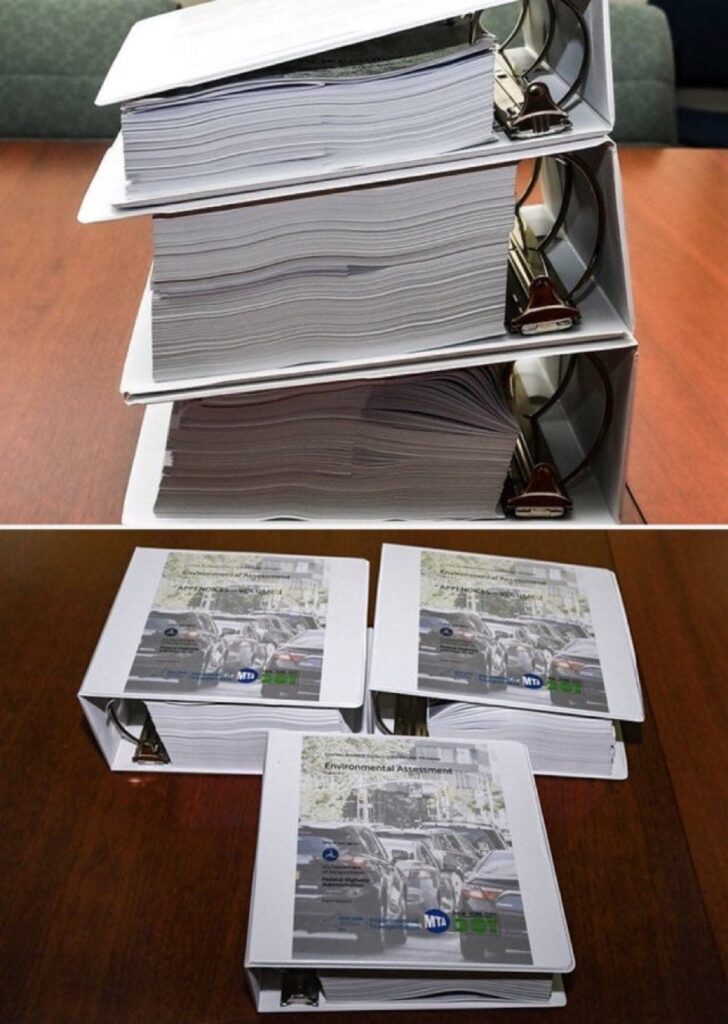

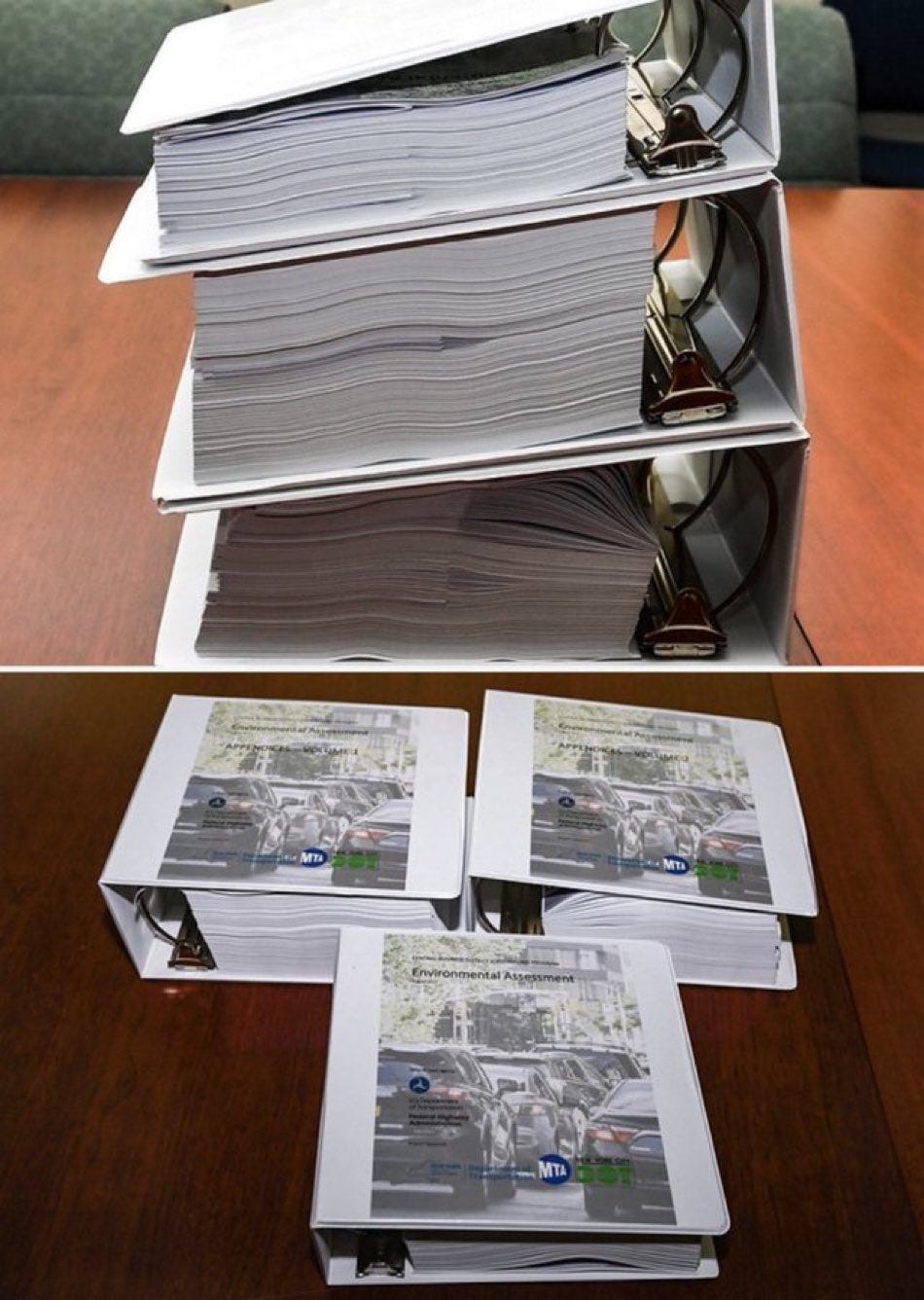

Alec Stapp: NYC teachers union claims the environmental review for congestion pricing wasn’t thorough enough. Actual photo of the 4,000-page environmental review:

Alec Stapp: Reminder that congestion pricing was passed by the democratically-elected state legislature in 2019. Vetocracy is bad.

That’s right. Reducing the use of cars via congestion pricing has been insufficiently studied in case it causes air pollution in other areas, and would cause ‘injustice.’ And the review pictured above means they did not take review seriously, it’s not enough.

It is amazing to me we put up with such nonsense.

Alternatively, it looks similar to this, technically the National Historic Preservation Act:

AP: Tribes, environmental groups ask US court to block $10 billion energy transmission project in Arizona.

Alec Stapp: The biggest clean energy project in the country is being sued by environmental groups.

This outdated version of “environmentalism” needs to die.

It’s time to build, not block.

The project is being sued under the National Historic Preservation Act. The NHPA is possibly the second most abused law in this space (the first being NEPA).

This is the last thing you see before your clean energy project gets sued into oblivion.

Here we have a lithium mine and a geothermal project in California, and conservation groups once again are suing.

E&E News: Environmental groups on Thursday sued officials who signed off on a lithium project in the Salton Sea that a top Biden official has helped advance.

Comité Civico del Valle and Earthworks filed the legal complaint in Imperial County Superior Court against county officials who approved conditional permits for Controlled Thermal Resources’ Hell’s Kitchen lithium and geothermal project.

The groups argue that the country’s approval of the direct lithium extraction and geothermal brine project near the southeastern shore of the Salton Sea violates county and state laws, such as the California Environmental Quality Act.

Alec Stapp: Conservation groups suing to stop a lithium and geothermal project in California. Yet another example of conservation groups at direct odds with climate goals. Clean energy deployment requires building stuff in the real world, full stop.

Armand Domalewski: so so so many environmental groups are just climate arsonists

And by rule of three, the kicker:

Thomas Hochman: This is the most classic NEPA story of all time: The US Forest Service wanted to implement a wildfire prevention plan, so it had to fill out an environmental impact statement. Before they could complete the environmental impact statement, though, half the forest burned down.

Scott Lincicome: 10/10. no notes. A little googling here reveals the kicker: the appellant apparently filed the appeal/complaint to protect the forest (a goshawk habitat)… that subsequently burned down bc of her appeal/complaint.

CEQA is like NEPA, only it is by California, and it is even worse.

Dan Federman: It breaks my brain that NIMBYs have succeeded in blocking coastal wind farms that aren’t visible from shore, but yet Santa Barbara somehow has oil rigs visible from its gorgeous beaches 🤯

Max Dubler: You have to understand that California environmental law is chiefly concerned with *preserving the environment that existed in 1972,not protecting nature. For example, oil companies sued under environmental law to block LA’s ban on oil drilling.

Alex Armlovich: According to CEQA, the California Environment of 1970 Quality Act, removing the oil derricks for renewables would impact the visual & cultural resources of this historic beach drilling site

Years of study & litigation needed to protect our heritage drilling environment 🛢️👨🏭⛽

Here is one CEQA issue. This also points out that you can write in all the exemptions you want, and none of that will matter unless those in charge actually use them.

Alec Stapp: Environmental review is now holding up bus sheltersby six months. Literally can’t even build the smallest physical infrastructure quickly.

Chris Elmendorf: Why is LA’s transit agency cowering before NIMBYs rather than invoking the new @Scott_Wiener-authored CEQA exemption for transit improvements?

Bus stops certainly would seem to meet SB 922’s definition of “transit prioritization project,” which includes “transit stop access and safety improvement.”

But instead of invoking the exemption, the city prepared a CEQA “negative declaration,” which is the most legally vulnerable kind of CEQA document.

It looks like city’s neg dec was made just months prior to effective date of SB 922. So what? City could have approved an exemption too as soon as SB 922 took effect.

Or city could approve it tomorrow.

Rather than putting bus shelters on hold just b/c a lawsuit was filed.

Halting transit projects just b/c a lawsuit was filed seems especially dumb at the present moment, when Leg has made clear it wants these projects streamlined and elite/journalist opinion has turned against CEQA abuse.

If a court dared to enjoin the project, there’d be uproar & Leg would probably respond by strengthening the transit exemption.

Just look at what the NIMBYs “won” by stopping 500 apartments on a valet parking lot in SF (AB 1633), or student housing in Berkeley (AB 1307).

Is this just a case of bureaucratic risk aversion (@pahlkadot) or autopiloting of dumb processes? Is there an actual problem with SB 922 that makes it unusable for ordinary LA bus stops?

Curious to hear from anyone who knows.

My presumption is it is basically autopiloting, that the people who realize it is dumb do not have the reach to the places where people don’t care. It is all, of course, madness.

The good news is that the recent CEQA ruling says that it should no longer give the ‘fullest possible protection’ to everything, so things should get somewhat better.

I wish this number were slightly higher for effect, but still, seriously:

R Street: 49% of CEQA lawsuits are against environmentally advantageous projects!

Somehow, rather than struggling to improve the situation, many Democrats seem to strive to make the inability to do things even worse.

For example, we have this thread from January detailing the proposed Clean Electricity Transmission Acceleration Act. Here are some highlights of an alternative even worse future, where anyone attempting to do anything is subject to arbitrary hold up for ransom, and also has to compensate any losers of any kind, including social and economic costs, and destroying any limitations on scope of issues. The bill even spends billions to fund these extractive oppositional efforts directly.

Chris Elmendorf: The bill defines “enviro impact” to include not only enviro impacts, but also “aesthetic, historic, cultural, economic, social, or health” effects. (Whereas CEQA is still about “physical environment”–even in the infamous Berkeley case.

The bill creates utterly open-ended authority for fed. agencies to demand a “community benefit agreement” as price of any permit for which an EIS was prepared. This converts NEPA from procedural statute into grant of substantive reg / exaction authority.

In exercising the “community benefit agreement” authority, what is a federal agency supposed to consider? Consideration #1 is the deepness of the permit-applicant’s pocket. Seriously.

And in case the new, expansive definition of “enviro impact” wasn’t clear enough, the bill adds that CBAs may be imposed to offset any *social or economic(as well as enviro) impacts of the project.

The bill would also destroy the caselaw that limits scope of enviro review to scope of agency’s regulatory discretion, not only via the CBA provision but also by expressly requiring analysis of effects “not within control of any federal agency.”

And the bill would send a torrent of federal dollars into the coffers of groups who’d exploit NEPA for labor or other side hustles. – there’s $3 billion of “community engagement” grants to arm nonprofits & others

…

And in case NEPA turned up to 11 isn’t enough, there’s also a new, judicially enforceable mandate for “community impact reports” if a project may affect an “environmental justice community.”

There’s also a wild provision that seems to prevent federal agencies from considering any project alternatives in an EIS unless (a) the alternative would have no adverse impact on any “overburdened community,” or (b) it serves a compelling interest *in that community.*

…

One more observation: the bill subtly nudges NEPA toward super-statute status by directing conflicts b/t NEPA “and any other provision of law” to be resolved in favor of NEPA.

Or we could have black-clad anarchists storming electric vehicle factories, as happened in Tesla’s plant in Berlin. Although we do have ‘Georgia greens’ suing over approval of an EV plant there.

It turns out everyone basically let this mess happen because Congress wanted to get home for Christmas? No one understood what they were doing?

This seems like it should be publicized more, as part of the justification for killing this requirement outright, and finding a better way to accomplish the same thing. It is amazing how often the worst laws have origin stories like this.

Patrick McKenzie: Sometimes we spend a trillion dollars because not spending a trillion dollars would require an exhausting amount of discussions and it is almost Christmas.

Please accept a trillion dollars as a handwavy gesture in the direction of the impact of NEPA; my true estimate if I gave myself a few hours to think would probably be higher.

I know everyone says that once you pass a regulation it is almost impossible to remove. But what if… we… did it anyway?

It is good that these exclusions are available. It is rather troublesome that they are so necessary?

Nicholas Bagley: A number of federal agencies have categorical exclusions from NEPA for … picnics.

If you need a special exception to make the lawyers comfortable with picnics, maybe you’ve gone too far?

“29. Approval of recreational activities (such as Coast Guard unit picnic) which do not involve significant physical alteration of the environment, increase disturbance by humans of sensitive natural habitats, or disturbance of historic properties, and which do not occur in, or adjacent to, areas inhabited by threatened or endangered species.”

I mean, modest proposal time, perhaps?

If your physical activity:

-

Does not significantly physically alter the environment.

-

Does not disturb sensitive natural habitats.

-

Does not disturb historic properties.

-

Does not occur in or adjacent to areas inhabited by threatened or endangered species.

Or, actually, how about if your physical activity:

-

Does not significantly physically alter the environment.

Then why are we not done? What is there we need to know, that this does not imply?

Shouldn’t we be able to declare this in a common sense way, and then get sued in court if it turns out we were lying or wrong, with penalties and costs imposed if someone sues in profoundly silly fashion, such as over a picnic?

The good news: We are getting some new ones.

Alec Stapp: Huge permitting reform news:

The Bureau of Land Management is giving geothermal energy exploration a categorical exclusion from environmental review under NEPA.

If you care about clean energy abundance, this is a massive win.

Arnab Datta: ICMYI – great news, BLM is adopting categorical exclusions to streamline permitting for geothermal exploration.

What’s the upshot? Exploration for geothermal resources should be a little bit easier.

As a result of the FRA (passed last year), agencies can now more easily adopt the categorical exclusions of other agencies. That’s what BLM is doing, adopting the CXs from the Navy and USFS.

Ex: Here’s the Navy CX. Applications to BLM for geophysical surveys will be easier.

Why is this important? BLM (and the federal government writ-large) owns a LOT of land, particularly in the Mountain West where heat resources are strongest, most ripe for geothermal production.

We previously recommended that BLM expand its CXs for geothermal exploration. This is a great first step, but there’s more to do.

Patrick McKenzie: I’ve been doing some work with a geothermal non-profit, and my inexpert understanding is that while first-of-their-kind projects are the immediate blocker, NEPA lawsuits were a major worry with expanding rollout to blue states after proof of concepts get accomplished and tweaked.

The (without loss of generality) Californias of the world are huge energy consumers, cannot simply import electricity from (without loss of generality) Texas (though you can tweak that assumption a tiny bit on margins), and local organized political opposition is a real factor.

If you’re curious as to why geothermal is likely to be a much larger part of U.S. and world energy mixes than you model currently, see this.

Short version: fracking makes it viable in many more places than it is currently.

There is a lot more to do on the exclusion front. It seems like obvious low-hanging fruit to exclude as many green projects as possible. Yes, this suggests the laws are bad and should be replaced entirely, but until then we work with the system we have.

Alec Stapp: Other federal agencies should start thinking about how to use categorical exclusions from NEPA environmental review to make it easier to build in the US.

Here’s some low-hanging fruit:

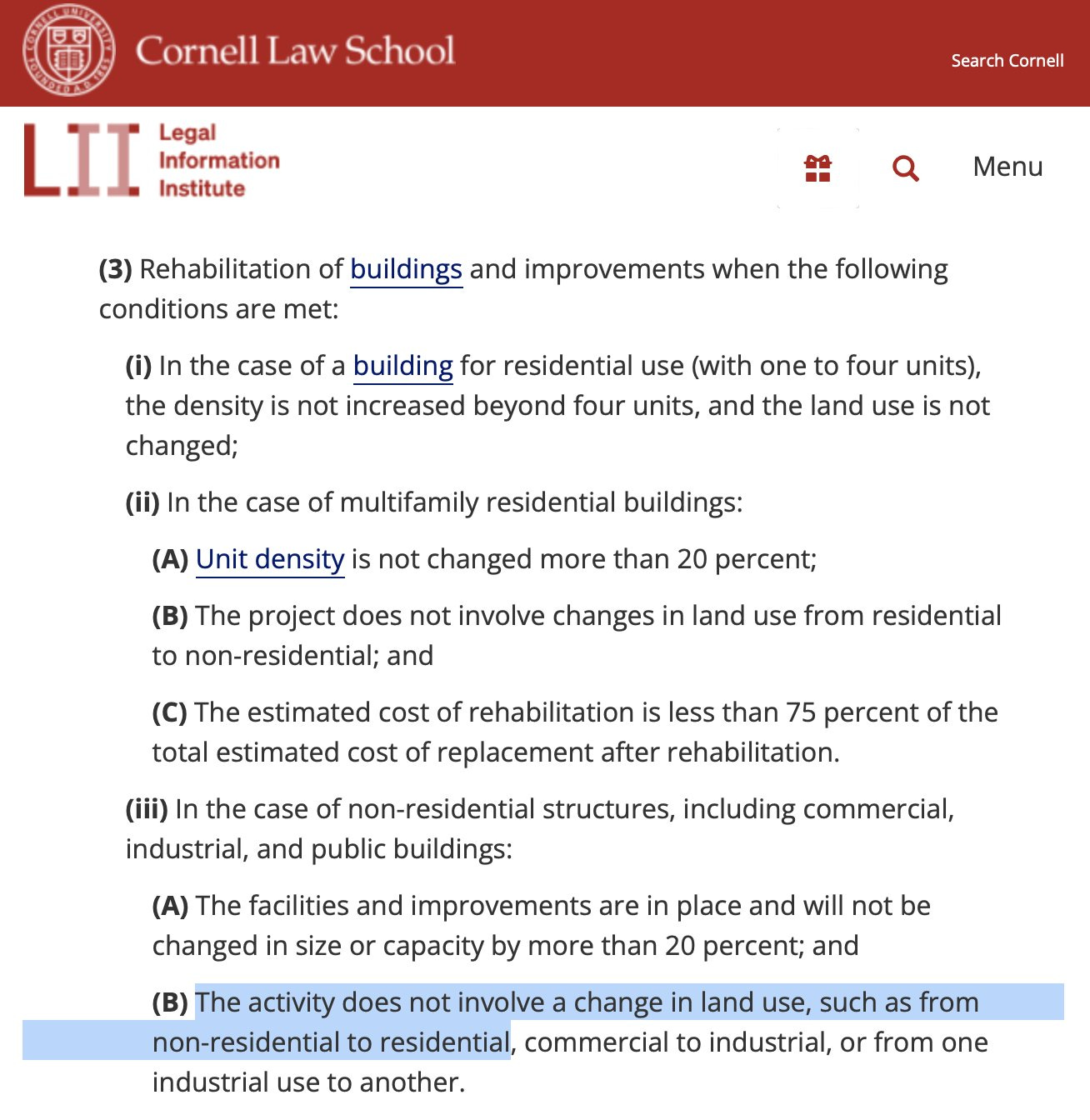

@HUDgov should update its categorical exclusion to cover office-to-residential conversions.

That seems like it should fall under ‘wait why do we even need an exclusion again?’

Alec Stapp: Good news on permitting reform!

The Department of Energy is giving a categorical exclusion from NEPA environmental review to:

– transmission projects that use existing rights of way

– solar projects on disturbed lands

– energy storage projects on disturbed lands

Sam Drolet: This is huge. It’s good to see agencies starting to use categorical exclusions in a sensible way to streamline permitting.

Christian Fong: A lot of great rules coming out right now from the Biden admin, but one that has gone under the radar is on NEPA reforms from the DOE! Specifically, expanding the list of projects that qualify for categorical exclusions, which can speed up NEPA reviews from 2 years to 2 months!

,,,

For solar, CXes were initially granted only if projects were built in a previously disturbed/developed land and were under 10 acres in size. This rule has removed the acreage limit, so that even projects 1000+ acres in size can still qualify if on previously disturbed lands.

A new CX was established for storage, with similar qualifications around previously disturbed/developed land, as well as the ability for projects to use a small bit of contiguous undisturbed land, as storage may be colocated with existing energy/tx/industry infrastructure.

…

Given full NEPA EISes can take 2 years, and new tx lines can take 10+ years to build, these rules are particularly important for improving tx capacity through reconductoring, GETs, etc. DOE just released its liftoff report on this topic here.

A new paper suggested a ‘a green bargain’ could be struck on permitting reform, that is a win for everyone. It misunderstands what people are trying to win.

Zachary Liscow: NEW PAPER: “Getting Infrastructure Built: The Law and Economics of Permitting,” on:

– What to consider in design of permitting rules

– The evidence

– A possible “green bargain” that benefits efficiency, the environment, & democracy

…

Infrastructure is often slowed by permitting rules. One example is NYC congestion pricing, which was passed by the legislature in 2019, had a 4,000-page environmental assessment, and is now subject to 5 lawsuits.

But how can we speed up permitting and make infrastructure less expensive, while still protecting the environment and promoting democratic participation?

…

Environmental permitting might be part of why infrastructure is so expensive in the US. Urban transit costs about 3x the rich/middle-income country average and 6x some European countries.

…

At the same time, US environmental outcomes aren’t particularly good. Based on the Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy’s Environmental Performance Index, the US (at 51, just the 25thpercentile) is considerably worse than the OECD average (at 58).

…

So what to do? I have a framework w/ 2 dimensions. 1: Improve the capacity of the executive to decide – for example, by limiting the power of litigation to delay. 2: Improve the capacity to plan, including by adding broad-based participation. Currently the US is weak along both.

I propose a “green bargain” that strengthens both executive power and capacity, empowering the executive to decide, but coupling that w/ increased capacity to plan, especially in ways that promote broad-based participation.

Can we create a win-win-win for:

-

Efficiency

-

Democracy

-

The Environment?

Yes, most certainly, in a big way. The current system is horribly inefficient in many ways that benefit neither democracy nor the environment, indeed frequently this problem is harmful to both. If these are the stakeholders, then there any number of reasonable ‘good governance’ plans one could use.

So what is the deal proposed? As far as I can tell it is this:

-

Increase executive power over decisions.

-

Rise standards required for judicial review and make court challenges harder in various ways – time limits, standing requirements, limits on later new objections, limits on challenges to negotiated agreements, more categorical exclusions.

-

Limits on court injunctions to stop projects.

-

Increase executive capacity on all levels of government so they can handle it.

-

Improve quality and scope of executive reviews and enhance public participation.

Do I support all of these proposals on the margin? Absolutely. Most would be good individually, the rest make sense as part of the package.

Do I think that this should be convincing to a sincere environmentalist, that they should trust that this will lead to good outcomes? Alas, my answer is essentially no, if this was applied universally.

I do think this should be convincing if it is applied exclusively to green energy projects and complementary infrastructure. If the end goal is solar panels or batteries, and one believes there is a climate crisis, then one should have a strong presumption that this should dominate local concerns and that delays and cost overruns kill projects.

Here is the other core problem: Many obstructionists do not want better outcomes.

If someone’s goal is to accomplish good things that make life better, such as reducing how much carbon is in the atmosphere or ensuring the air and water are clean, and is willing to engage in trade to make the world improve and not boil, but has different priorities and weightings and values than you have?

Then you can and should engage in trade, talk price. We can make a deal.

If someone’s goal is to stop development and efficiency because they believe development and efficiency are bad, either locally or globally? If they think humanity and civilization (or at least your civilization) are bad and want them to suffer and repent? Or consider every downside a sacred value that should veto any action?

If they actively do not want the problem solved because they want to use the problem as leverage to demand other things, and you are not a fan of those other things?

Then you are very much out of luck. There is no deal.

My expectation is that even if your deal is a clear win for people and the environment, in way they can trust, you are going to get a lot of opposition from environmental groups anyway. Here, I worry that this proposal also does not give them sufficient reason to trust. Half the time the executive will be a Republican.

John Arnold: I used to think decarbonization was hard because voters prioritized the goals of the energy system in the following order:

Affordable

Reliable

Secure

Clean

But I missed one. The actual order of prioritization is:

Jobs

Affordable

Reliable

Secure

Clean

That, however infuriating, is something we can work with. There is no inherent conflict between jobs and energy. It trades off with affordable, but we can talk price.

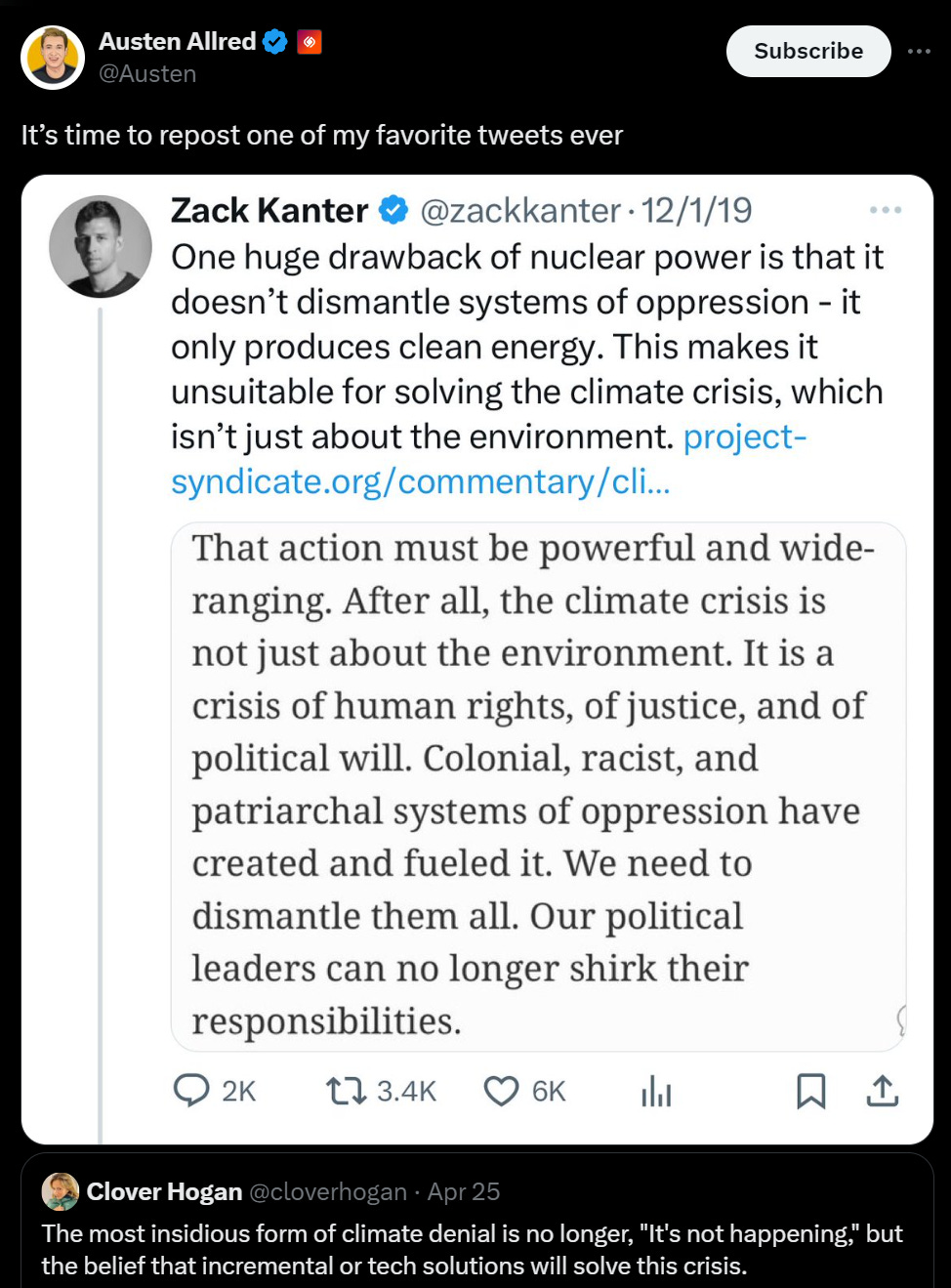

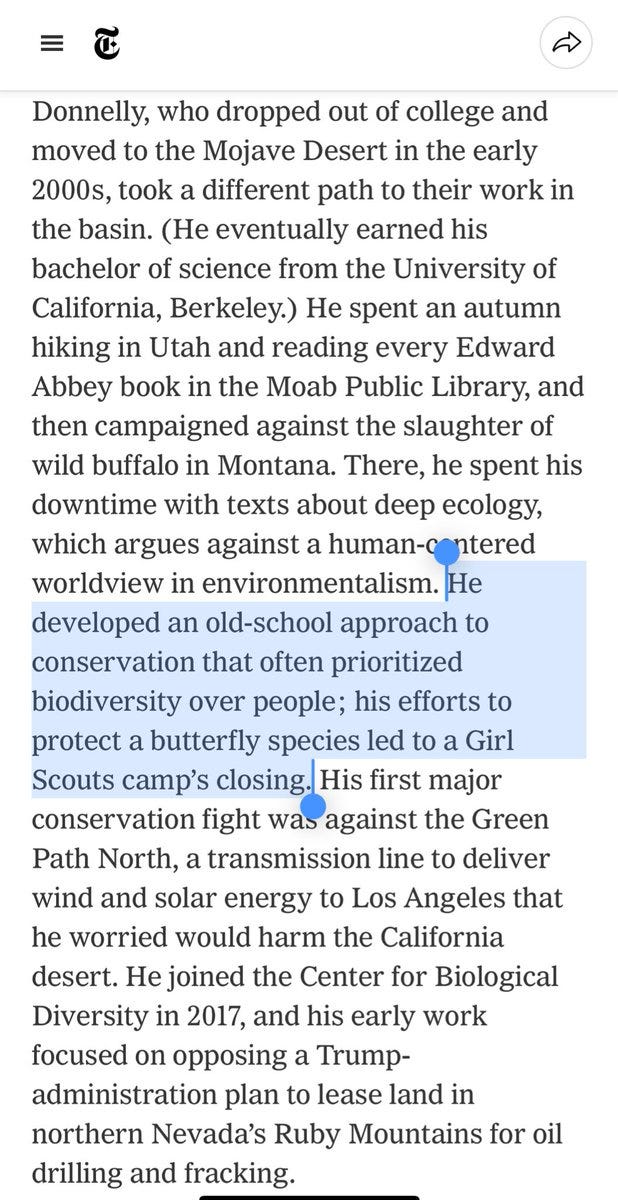

I have so had it with all the ‘yes this saves the Earth but think of the local butterfly species’ arguments, not quite literally this case but yeah, basically.

Alec Stapp: Very funny to me that the framing of this NYT article is sincerely like:

“What’s more important: Saving earth or satisfying the idiosyncratic preferences of a small handful of activists?”

That’s not a close call!

Act fast, this closes July 15: Introducing the Modernizing NEPA Challenge.

In alignment with ongoing efforts at DOT to improve the NEPA process, this Modernizing NEPA Challenge seeks:

To encourage project sponsors to publish documents associated with NEPA that increase accessibility and transparency for the public, reviewing agencies, and historically under-represented populations and

To incentivize project sponsors to implement collaborative, real-time agency reviews to save time and improve the quality of documents associated with NEPA.

More details at the link. The goal is to get collaborative tools and documents, and interactive documents, that make it easier to navigate the NEPA process.

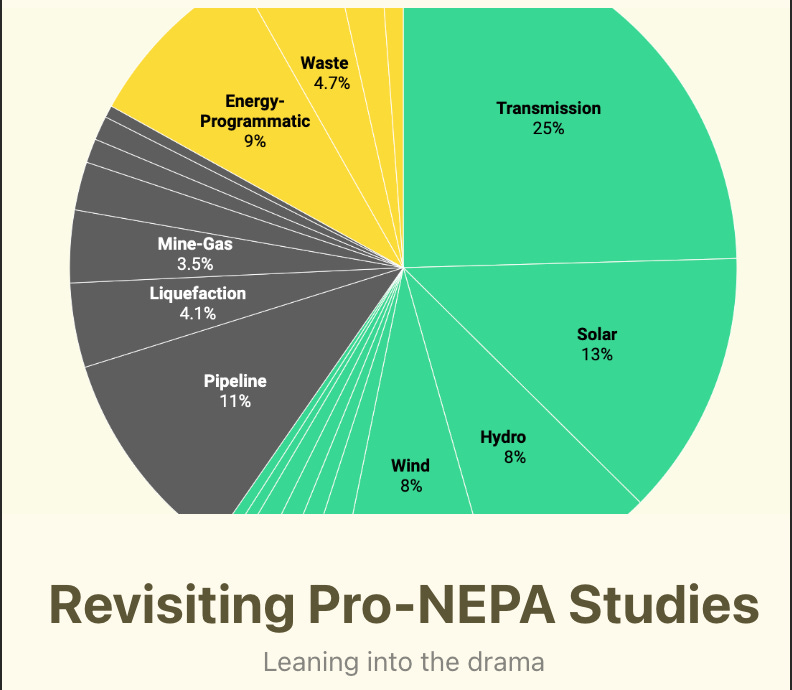

Thomas Hochman: Almost every pro-NEPA argument can be traced back to two studies: Adelman’s “Permitting Reform’s False Choice” and Ruple’s “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden.”

Note that the majority of the pie is green, as in clearly net good for the planet, even if you take the position that fossil fuels are always bad – and I’d argue the opposite, that anything replacing coal on the margin is obviously net good too.

Ruple’s study analyzes 1,499 federal court opinions involving NEPA challenges from 2001-2013. He comes up with two key findings:

Only about 0.22% of NEPA decisions (1 in 450) face legal challenges

Less than 1% of NEPA reviews are environmental impact statements (EISs), and about 5% of NEPA reviews are environmental assessments (EAs).

…

But in “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden,” Ruple makes the same error that he’s made throughout his work on permitting: he takes the average volume of litigation across all NEPA reviews and makes a conclusion about NEPA’s impact on infrastructure in particular. In other words, his denominator is wildly inflated.

Ruple’s dataset includes NEPA reviews at every level of stringency: categorical exclusions (CatExes), EAs, and EISs. And as Ruple himself points out, around 95% of NEPA reviews are CatExes. This is because NEPA is triggered by almost every federal action, and thus CatExes are required for everything from federal hiring to, yes, picnics.

…

Their findings are remarkable: solar, pipeline, wind, and transmission projects saw litigation rates of 64%, 50%, 38%, and 31% respectively. The cancellation rates for each of these project types were also extraordinarily high, ranging from 12% to 32%.

Barring a rebuttal I do not expect, that seems definitive to me.

What about the other study?

The basic flaw in Adelman’s analysis is that he sees the low percentage of renewable projects that undergo NEPA as evidence that NEPA isn’t a big deal. In reality, the exact opposite is true.

As in, NEPA is so obnoxious that where there would be NEPA issues, the projects never even get proposed. We only get renewable projects, mostly, where they have sufficient protections from this. Again, this seems definitive to me.

My grand solution to NEPA would be to repeal the paperwork and impact statement requirements, and replace them with a requirement for cost-benefit analysis. That is a complex proposal that I am confident would work if done properly, but which I agree is tricky.

The grander, simpler solution is repeal NEPA first and ask questions later. At this point, I think that’s the play.

A solution in bewteen those two would perhaps be to change the remedy for failure, so that any little lapse does not stop an entire project.

This is another approach to the fundamental problem of sacred values versus cost-benefit.

Right now, we are essentially saying that a wide variety of potential harms are sacred values, that we would not compromise at any price, such that if there is any danger that they might be compromised then that is a full prohibition.

But of course that is crazy. With notably rare exceptions, that is not how most anything should ever work.

Thus, an alternative solution is to keep all the requirements in place, and allow all the lawsuits to proceed.

But we change the remedy from injunctions to damages.

As in, suppose a group sues you, and says that your project might violate some statute or do harm in some way. Okay, fine. They file that claim, it is now established. You can choose to wait until the claim is resolved, if the claim actually is big enough and plausible enough that you are worried they might win.

Or, you can convince an insurance company to post a bond for you, covering the potential damages (and let’s say you can get dinged for double or triple the actual harms, more if you ‘did it on purpose’ and knew you were breaking the rules, in some sense, or something). So you can choose to do the project anyway, without a delay, and if it turns out you messed up or broke the rules and the bill comes due, then you have to pay that bill. And since it is a multiplier, everyone is still ahead.

Discussion about this post

NEPA, Permitting and Energy Roundup #2 Read More »