Using pollen to make paper, sponges, and more

Softening the shell

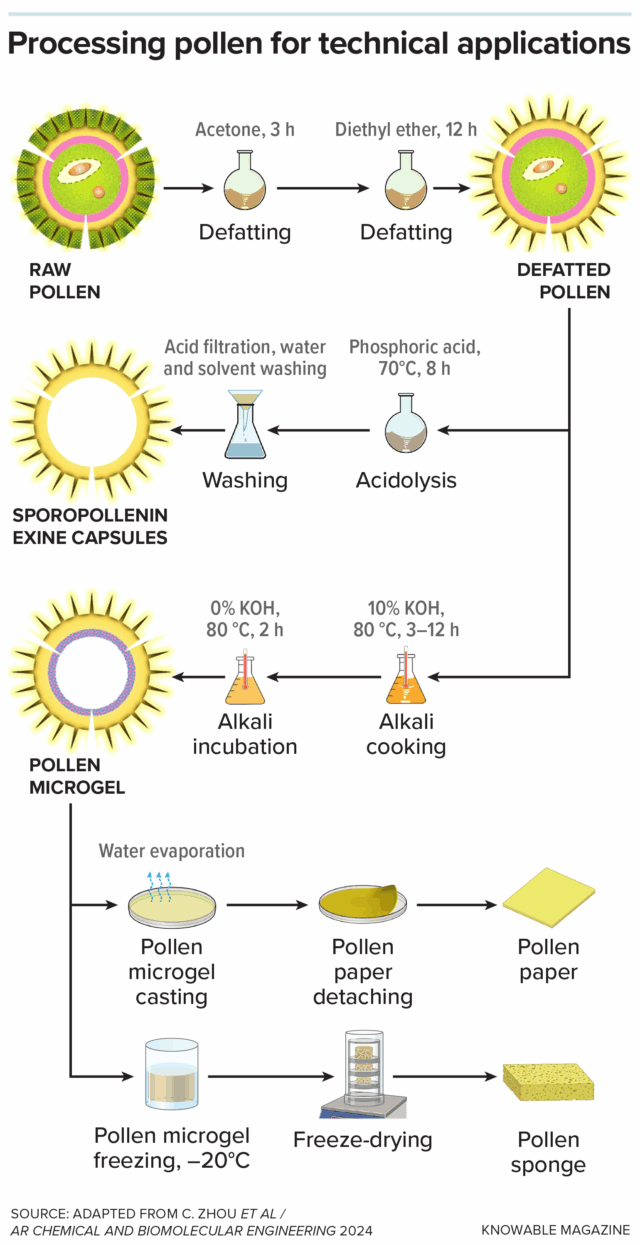

To begin working with pollen, scientists can remove the sticky coating around the grains in a process called defatting. Stripping away these lipids and allergenic proteins is the first step in creating the empty capsules for drug delivery that Csaba seeks. Beyond that, however, pollen’s seemingly impenetrable shell—made up of the biopolymer sporopollenin—had long stumped researchers and limited its use.

A breakthrough came in 2020, when Cho and his team reported that incubating pollen in an alkaline solution of potassium hydroxide at 80° Celsius (176° Fahrenheit) could significantly alter the surface chemistry of pollen grains, allowing them to readily absorb and retain water.

The resulting pollen is as pliable as Play-Doh, says Shahrudin Ibrahim, a research fellow in Cho’s lab who helped to develop the technique. Before the treatment, pollen grains are more like marbles: hard, inert, and largely unreactive. After, the particles are so soft they stick together easily, allowing more complex structures to form. This opens up numerous applications, Ibrahim says, proudly holding up a vial of the yellow-brown slush in the lab.

When cast onto a flat mold and dried out, the microgel assembles into a paper or film, depending on the final thickness, that is strong yet flexible. It is also sensitive to external stimuli, including changes in pH and humidity. Exposure to the alkaline solution causes pollen’s constituent polymers to become more hydrophilic, or water-loving, so depending on the conditions, the gel will swell or shrink due to the absorption or expulsion of water, explains Ibrahim.

For technical applications, pollen grains are first stripped of their allergy-inducing sticky coating, in a process called defatting. Next, if treated with acid, they form hollow sporopollenin capsules that can be used to deliver drugs. If treated instead with an alkaline solution, the defatted pollen grains are transformed into a soft microgel that can be used to make thin films, paper, and sponges. Credit: Knowable Magazine

This winning combination of properties, the Singaporean researchers believe, makes pollen-based film a prospect for many future applications: smart actuators that allow devices to detect and respond to changes in their surroundings, wearable health trackers to monitor heart signals, and more. And because pollen is naturally UV-protective, there’s the possibility it could substitute for certain photonically active substrates in perovskite solar cells and other optoelectronic devices.

Using pollen to make paper, sponges, and more Read More »