Switching water sources improved hygiene of Pompeii’s public baths

From well to aqueduct

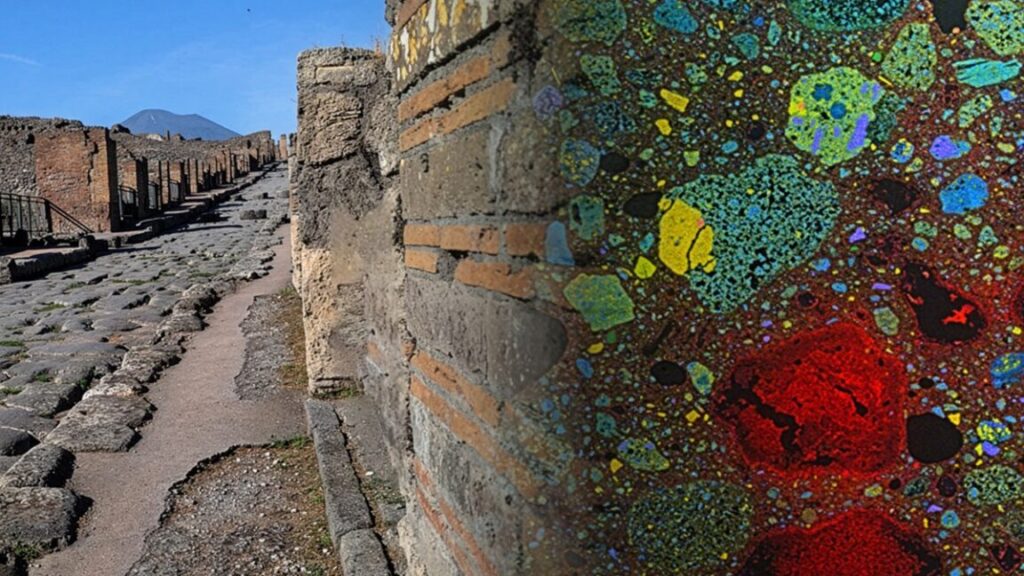

The specific sites studied included the Stabian baths and related structures, which were built after 130 BCE and remained active until the aforementioned eruption; the Republican baths, built around the same period but abandoned around 30 BCE; the Forum baths, built after 80 BCE; and the aqueduct and its 14 water towers, constructed during the Augustan period.

There were variations in the chemical composition of the deposits, indicating the replacement of boilers for heating water and a renewal of water pipes in the infrastructure of Pompeii, particularly during the time period when modifications were being made to the Republican baths. The results for the Republican baths’ heated pools, for instance, showed clear contamination from human activity, specifically human waste (sweat, sebum, urine, or bathing oil), which suggests the water wasn’t changed regularly.

That is consistent with the limitations of supplying water at the time; the water-lifting machines could really only refresh the water about once a day. After the well shaft was enlarged, the carbonate deposits were much thinner, evidence of technological improvements that reduced sloshing as the water was raised. Once the aqueduct had been built, the bathing facilities were expanded with a likely corresponding improvement in hygiene.

On the whole, the aqueduct was a net good for Pompeii. “The changes in the water supply system of Pompeii revealed by carbonate deposits show an evolution from well-based to aqueduct-based supply with an increase in available water volume and in the scale of the bathing facilities, and likely an increase in hygiene,” the authors concluded. Granted, there was evidence of lead contamination in the water, particularly that supplied by the aqueduct, but carbonate deposits in the lead pipes seem to have reduced those levels over time.

The results may also help resolve a scientific debate about the origins of the aqueduct water: Was it water from the town of Avella that connected to the Aqua Augusta aqueduct or from the wells of Pompeii/springs of Vesuvius? Per the authors, the stable isotope composition of carbonate in the aqueduct is inconsistent with carbonate from volcanic rock sources, thus supporting the Avella source hypothesis.

PNAS, 2025. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2517276122 (About DOIs).

Switching water sources improved hygiene of Pompeii’s public baths Read More »