Research roundup: 6 cool stories we almost missed

A lip-syncing robot, Leonardo’s DNA, and new evidence that humans, not glaciers, moved stones to Stonehenge

Credit: Yuhang Hu/Creative Machines Lab

It’s a regrettable reality that there is never enough time to cover all the interesting scientific stories we come across each month. So every month, we highlight a handful of the best stories that nearly slipped through the cracks. January’s list includes a lip-syncing robot; using brewer’s yeast as scaffolding for lab-grown meat; hunting for Leonardo da Vinci’s DNA in his art; and new evidence that humans really did transport the stones to build Stonehenge from Wales and northern Scotland, rather than being transported by glaciers.

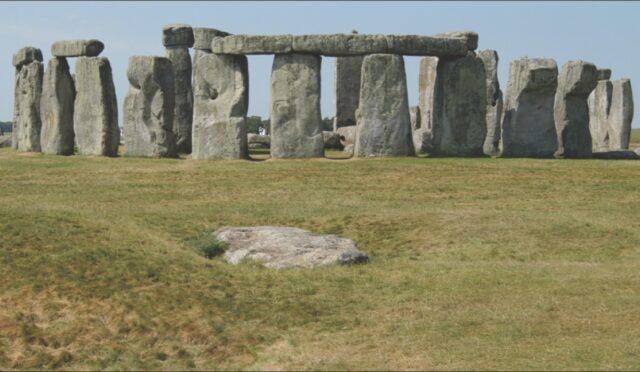

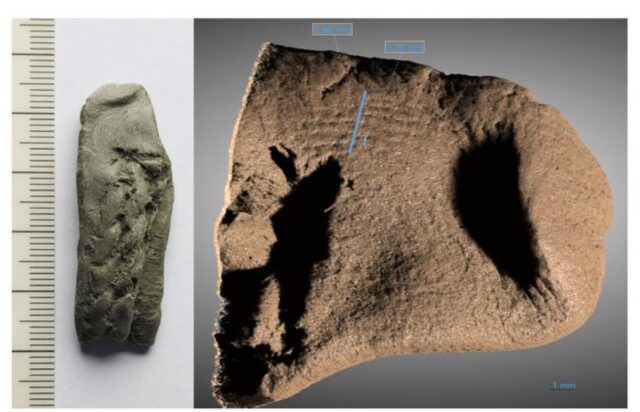

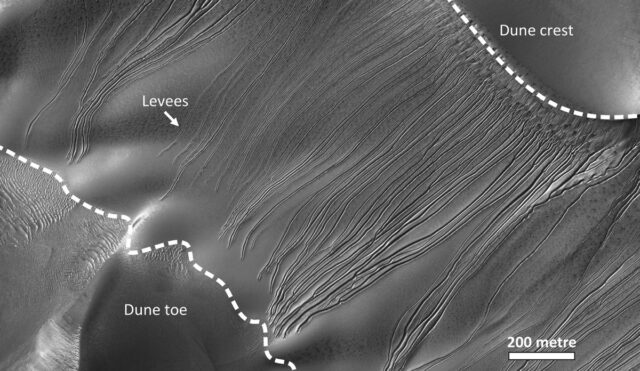

Humans, not glaciers, moved stones to Stonehenge

Credit: Timothy Darvill

Stonehenge is an iconic landmark of endless fascination to tourists and researchers alike. There has been a lot of recent chemical analysis identifying where all the stones that make up the structure came from, revealing that many originated in quarries a significant distance away. So how were the stones transported to their current location?

One theory holds that glaciers moved the bluestones at least part of the way from Wales to Salisbury Plain in southern England, while others contend that humans moved them—although precisely how that was done has yet to be conclusively determined. Researchers at Curtin University have now produced the strongest scientific evidence to date that it was humans, not glaciers, that transported the stones, according to a paper published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Curtin’s Anthony Clarke and co-authors relied on mineral fingerprinting to arrive at their conclusions. In 2024, Clarke’s team discovered the Stonehenge Altar Stone originated from the Orkney region in the very northeast corner of Scotland, rather than Wales. This time, they analyzed hundreds of zircon crystals collected from rivers close to the historic monument, looking for evidence of Pleistocene-era sediment. Per Clarke, if the stones had “sailed” to the plain from further north, there would be a distinct mineral signature in that sediment as the transported rocks eroded over time. They didn’t find that signature, making it far more likely that humans transported the stone.

DOI: Communications Earth & Environment, 2026. 10.1038/s43247-025-03105-3 (About DOIs).

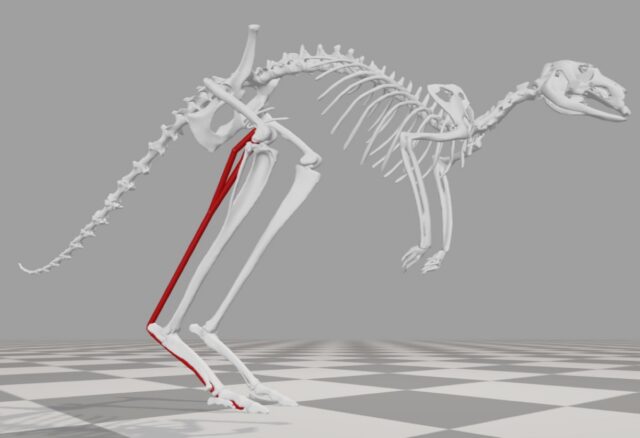

When grasshoppers fly

Credit: Princeton University/Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy

Everyone knows grasshoppers can hop, but they can also flap their wings, jump, and glide, moving seamlessly across both the ground and through the air. That ability inspired scientists from Princeton University to devise a novel approach to building robotic wings, according to a paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. This could one day enable multimodal locomotion for miniature robots with extended flight times.

According to the authors, grasshoppers have two sets of wings: forewings and hindwings. Forewings are mostly used for protection and camouflage, while the latter are involved in flapping and gliding, and are corrugated to allow them to fold into the insect’s body. The team took CT scans to capture the geometry of grasshopper wings and used the scans to 3D print model wings with varying designs. Next they tested each variant in a water channel to study how water flowed around the wing, isolating key features like a wing’s shape or corrugation to see how this impacted the flow.

Once they had perfected their design, they printed new wings and attached them to small frames to create grasshopper-sized gliders. The team then launched the gliders across the lab and used motion capture to evaluate how well they flew. The glider performed as well as actual grasshoppers. In addition, they found that a smooth wing resulted in more efficient gliding. So why do real grasshopper wings have corrugations? The authors suggest that these evolved because they help with executing steep angles.

DOI: Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2026. 10.1098/rsif.2025.0117 (About DOIs).

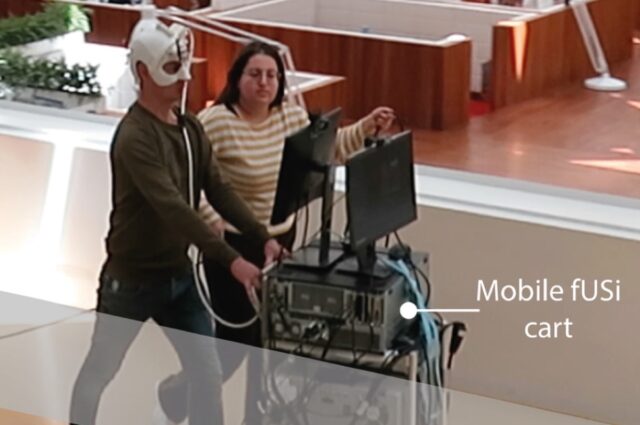

Lip-syncing robot

Credit: Yuhang Hu/Creative Machines Lab

Humanoid robots are fascinating, but nobody would mistake them for actual humans, in part because even the ones that have faces are far too limited in facial gestures, including lip motion—hence, the “Uncanny Valley.” Columbia University engineers have now created a robot capable of learning facial lip motions for speaking and singing. According to a paper published in Science Robotics, the resulting robotic face was able to speak words in several different languages and sing an AI-generated song. (Its AI-generated debut album is aptly titled hello world.).

What makes human faces so uniquely capable of expression are the dozens of muscles lying just under the skin. Robotic faces are rigid and hence only have a limited range of motion. The Columbia team built their robotic face out of flexible material augmented with 26 motors (actuators). The robot learned to how its face moved in response to different actuator activity by watching itself in a mirror as it attempted thousands of random facial expressions. Eventually it learned how to achieve specific facial gestures.

The next step was to let the robot watch recorded videos of humans talking and singing, augmented with an AI algorithm that enabled it to learn exactly how the human mouths moved when performing those tasks so it could lip sync along. The resulting lip motion wasn’t perfect; the robot struggled with “B” and “W” sounds in particular. But the authors believe the robot will improve with more practice; combining this ability with ChatGPT or Gemini could further improve its lip-syncing ability.

DOI: Science Robotics, 2026. 10.1126/scirobotics.adx3017 (About DOIs).

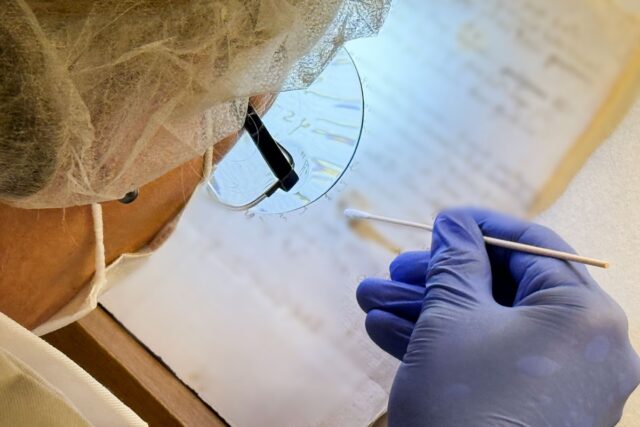

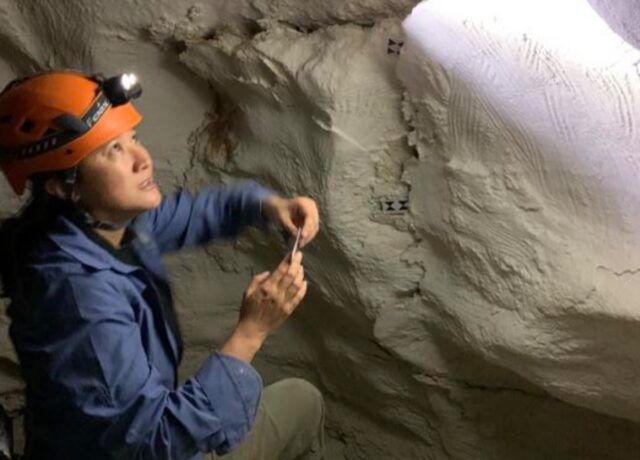

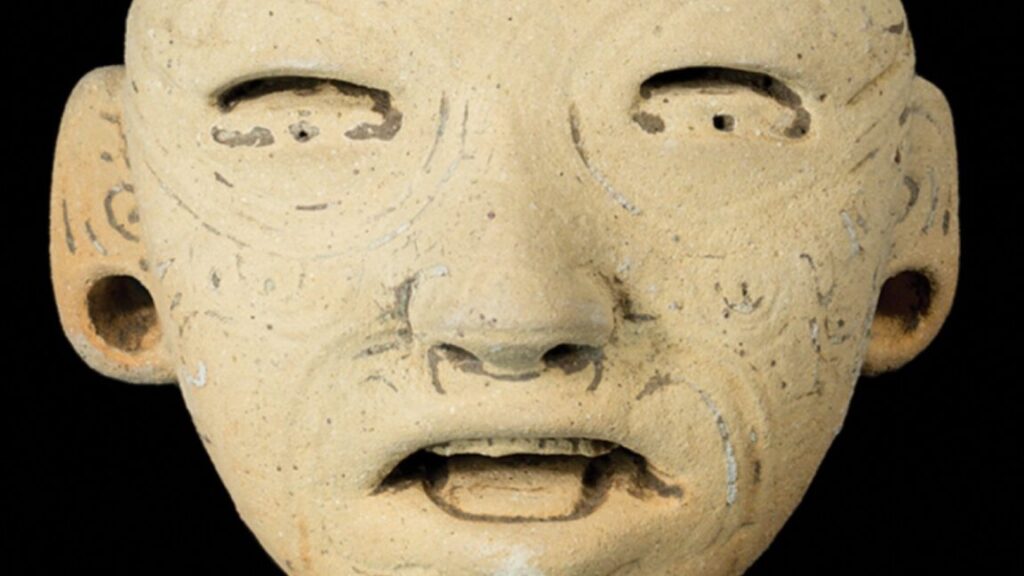

Is Leonardo’s DNA preserved in his art?

Credit: Paola Agazzi / Archivio di Stato di Prato / Italian Ministry of Culture

In 2020, scientists analyzed the microbes found on several of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings and discovered that each had its own distinct microbiome/. A second team, working with the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project in France, collected and analyzed swabs taken from centuries-old art in a private collection housed in Florence, Italy. They concluded that microbial signatures could be used to differentiate artwork according to the materials used—dubbing this emerging subfield “arteomics.”

Yet another team collaborating with the project painstakingly assembled Leonardo’s family tree in 2021, spanning 21 generations from 1331 to the present, resulting a full-length book published last year. The idea was that this will one day provide a means of conducting DNA testing to confirm whether the bones interred in Leonardo’s grave are actually the his. And now the project’s scientists are back with a preprint posted to the bioRxiv, announcing the successful sequencing of human DNA collected from a handful of artifacts associated with Leonardo—including a drawing of the Holy Child that some scholars attribute to Leonardo, as well as letters from a da Vinci family member.

The team lightly swabbed samples from the artifacts’ surfaces and were able to recover human Y-chromosome sequences from several of the samples. Several of these sequences were related and the authors speculate that some might even be Leonardo’s, although they cautioned that the samples would need to be compared to samples taken from the artist’s notebooks, burial site, and family tomb to make a definitive identification. The authors also found DNA from bacteria, fungi, flowers, and animals in some of the samples, as well as traces of viruses and parasites.

DOI: bioRxiv, 2026. 10.64898/2026.01.06.697880 (About DOIs).

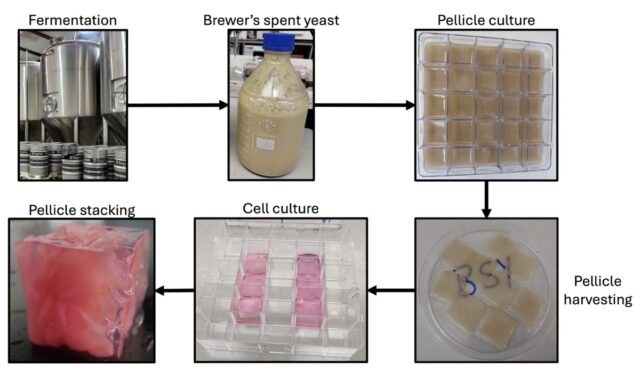

From pint to plate

Credit: Christian Harrison et al., 2026

Lab-grown meat is often touted as a more environmentally responsible alternative to the real deal, but carnivorous consumers are often put off by the unappealing mouthfeel and texture (and, for me, a weird oily aftertaste). A new method using spent brewer’s yeast to make edible “scaffolding” for cultivating meat in the lab might one day offer a solution, according to a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition.

Typically, a nutrient broth is used as a source of bacteria for the scaffolding. But Richard Day of University College London and his co-authors decided to use brewer’s yeast, usually discarded as waste, to culture a species of bacteria known for making high-quality cellulose. Then they tested the mechanical and structural properties of that cellulose with a “chewing machine.” They concluded that the cellulose made from spent brewer’s yeast was much closer in texture to real meat than the cellulose scaffolding made from a nutrient broth. The next step is to incorporate fat and muscle cells into the cellulose, as well as testing yeast from different kinds of beer.

DOI: Frontiers in Nutrition, 2026. 10.3389/fnut.2025.1656960 (About DOIs).

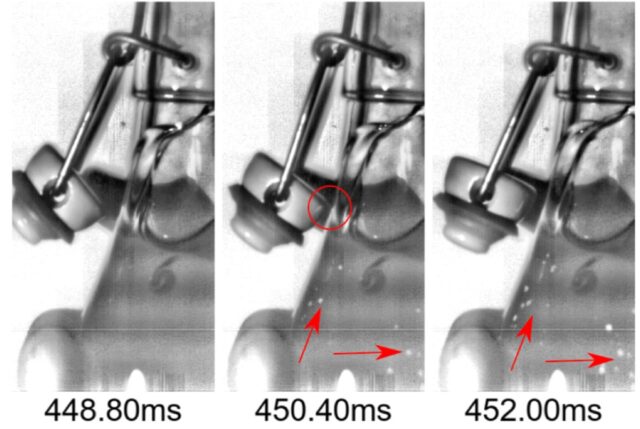

Water-driven gears

New York University scientists created a gear mechanism that relies on water to generate movement. For some conditions, the rotors spin in the same direction like pulleys looped together with a belt.

Gears have been around for thousands of years; the Chinese were using them in two-wheeled chariots as far back as 3000 BCE, and they are a mainstay in windmills, clocks, and the famed Antikythera mechanism. Roboticists also use gears in their inventions, but whether they are made of wood, metal or plastic, such gears tend to be inflexible and hence more prone to breakage. That’s why New York University mathematician Leif Reistroph and colleagues decided to see if flowing air or water could be used to rotate robotic structures.

Ristroph’s lab frequently addresses all manner of colorful real-world puzzles: fine-tuning the recipe for the perfect bubble, for instance; exploring the physics of the Hula-Hoop; or the formation processes underlying so-called “stone forests” common in China and Madagascar. In 2021, his lab built a working Tesla valve, in accordance with the inventor’s design; the following year they studied the complex aerodynamics of what makes a good paper airplane—specifically what is needed for smooth gliding; and in 2024 they cracked the conundrum of the “reverse sprinkler” problem that physicists like Richard Feynman, among others, had grappled with since the 1940s.

For their latest paper, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, Ristroph et al. wanted to devise something that functioned like a gear only with flowing liquid driving the motion, instead of teeth grinding against each other. They conducted a series of experiments in which they immersed cylindrical rotors in a glycerol-and-water solution. One cylinder would rotate while the other was passive.

They found that the rotating cylinder, combined with fluid flow, was sufficient to induce rotation in the passive cylinder. The flows functioned much in the same way as gear teeth when the cylinders were close together. Moving the cylinders further apart caused the active cylinder to rotate faster, looping the flows around the passive cylinder—essentially mimicking a belt and pulley system.

DOI: Physical Review Letters, 2026. 10.1103/m6ft-ll2c (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Research roundup: 6 cool stories we almost missed Read More »