Pentagon begins deploying new satellite network to link sensors with shooters

“This is the first time we’ll have a space layer fully integrated into our warfighting operations.”

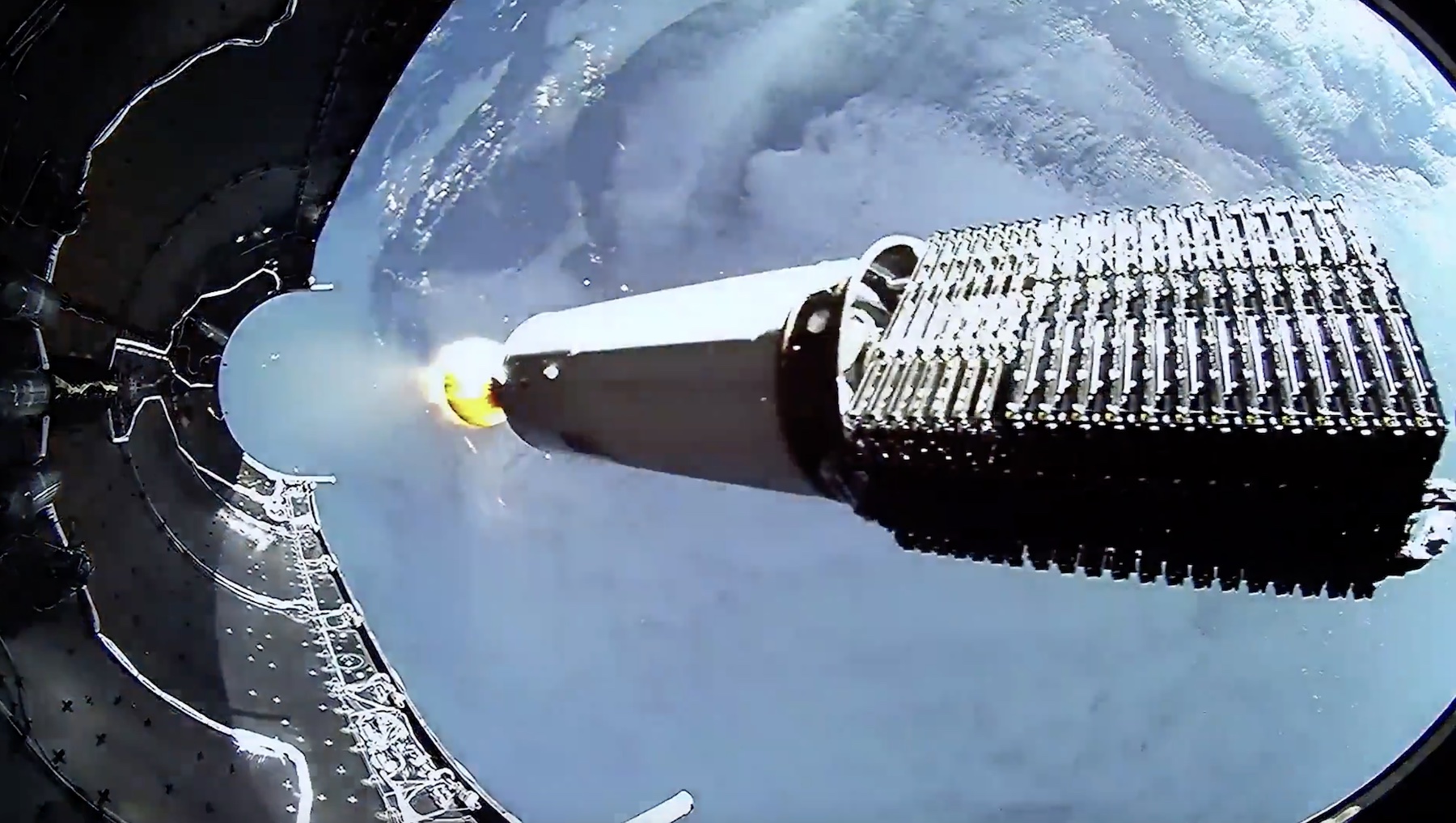

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, with a payload of 21 data-relay satellites for the US military’s Space Development Agency. Credit: SpaceX

The first 21 satellites in a constellation that could become a cornerstone for the Pentagon’s Golden Dome missile-defense shield successfully launched from California Wednesday aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

The Falcon 9 took off from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, at 7: 12 am PDT (10: 12 am EDT; 14: 12 UTC) and headed south over the Pacific Ocean, heading for an orbit over the poles before releasing the 21 military-owned satellites to begin several weeks of activations and checkouts.

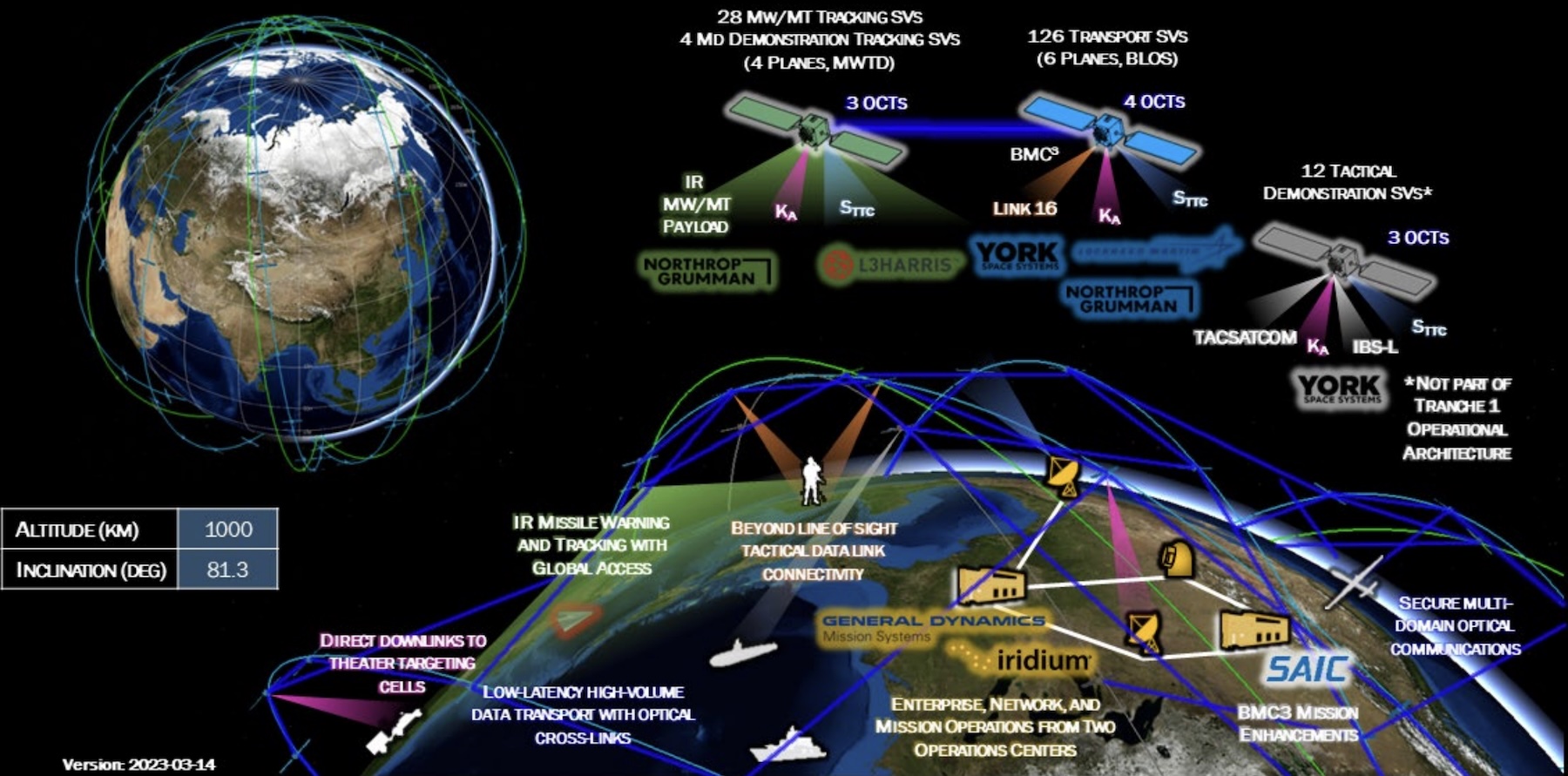

These 21 satellites will boost themselves to a final orbit at an altitude of roughly 600 miles (1,000 kilometers). The Pentagon plans to launch 133 more satellites over the next nine months to complete the build-out of the Space Development Agency’s first-generation, or Tranche 1, constellation of missile-tracking and data-relay satellites.

“We had a great launch today for the Space Development Agency, putting this array of space vehicles into orbit in support of their revolutionary new architecture,” said Col. Ryan Hiserote, system program director for the Space Force’s assured access to space launch execution division.

Over the horizon

Military officials have worked for six years to reach this moment. The Space Development Agency (SDA) was established during the first Trump administration, which made plans for an initial set of demonstration satellites that launched a couple of years ago. In 2022, the Pentagon awarded contracts for the first 154 operational spacecraft. The first batch of 21 data-relay satellites built by Colorado-based York Space Systems is what went up Wednesday.

“Back in 2019, when the SDA was stood up, it was to do two things. One was to make sure that we can do beyond line of sight targeting, and the other was to pace the threat, the emerging threat, in the missile-warning and missile-tracking domain. That’s what the focus has been,” said Gurpartap “GP” Sandhoo, the SDA’s acting director.

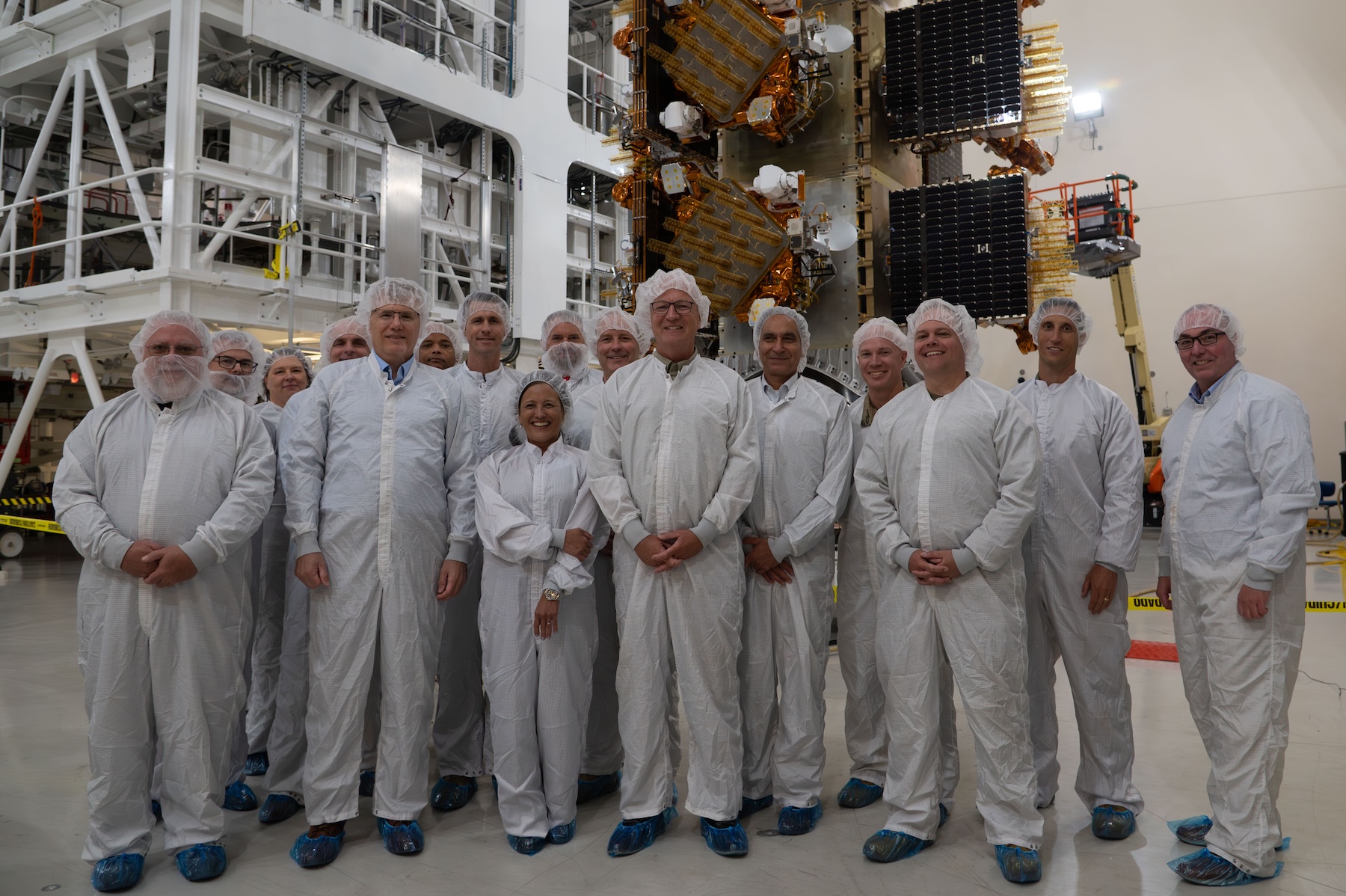

Secretary of the Air Force Troy Meink and Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) pose with industry and government teams in front of the Space Development’s first 21 operational satellites at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California. Cramer is one the most prominent backers of the Golden Dome program in the US Senate. Credit: US Air Force/Staff Sgt. Daekwon Stith

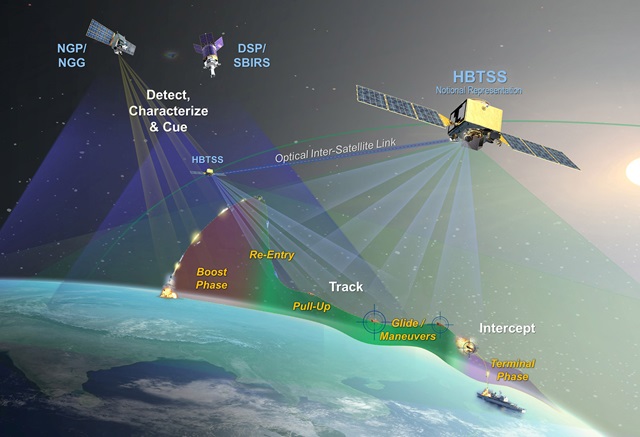

Historically, the military communications and missile-warning networks have used a handful of large, expensive satellites in geosynchronous orbit some 22,000 miles (36,000 kilometers) above the Earth. This architecture was devised during the Cold War and is optimized for nuclear conflict and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

For example, the military’s ultra-hardened Advanced Extremely High Frequency satellites in geosynchronous orbit are designed to operate through an electromagnetic pulse and nuclear scintillation. The Space Force’s missile-warning satellites are also in geosynchronous orbit, with infrared sensors tuned to detect the heat plume of a missile launch.

The problem? Those satellites cost more than $1 billion a pop. They’re also vulnerable to attack from a foreign adversary. Pentagon officials say the SDA’s satellite constellation, officially called the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, is tailored to detect and track more modern threats, such as smaller missiles and hypersonic weapons carrying conventional warheads. It’s easier for these missiles to evade the eyes of older early warning satellites.

What’s more, the SDA’s fleet in low-Earth orbit will have numerous satellites. Losing one or several satellites to an attack would not degrade the constellation’s overall capability. The SDA’s new relay satellites cost between $14 and $15 million each, according to Sandhoo. The total cost of the first tranche of 154 operational satellites totals approximately $3.1 billion.

Multi-mission satellites

These satellites will not only detect and track ballistic and hypersonic missile launches; they will also transmit signals between US forces using an existing encrypted tactical data link network known as Link 16. This UHF system is used by NATO and other US allies to allow military aircraft, ships, and land forces to share tactical information through text messages, pictures, data, and voice communication in near real time, according to the SDA’s website.

Up to now, Link 16 radios were ubiquitous on fighter jets, helicopters, naval vessels, and missile batteries. But they had a severe limitation. Link 16 was only able to close a radio link with a clear line of sight. The Space Development Agency’s satellites will change that, providing direct-to-weapon connectivity from sensors to shooters on Earth’s surface, in the air, and in space.

The relay satellites, which the SDA calls the transport layer, are also equipped with Ka-band and laser communication terminals for higher-bandwidth connectivity.

“What the transport layer does is it extends beyond the line of sight,” Sandhoo said. “Now, you’re able to talk not only to within a couple of miles with your Link 16 radios, (but) we can use space to, let’s say, go from Hawaii out to Guam using those tactical radios, using a space layer.”

The Space Development Agency’s “Tranche 1” architecture includes 154 operational satellites, 126 for data relay and 28 for missile tracking. With this illustration, the SDA does its best to show how the complex architecture is supposed to work. Credit: Space Development Agency

Another batch of SDA relay satellites will launch next month, and more will head to space in November. In all, it will take 10 launches to fully deploy the SDA’s Tranche 1 constellation. Six of those missions will carry data-relay satellites, and four will carry satellites with sensors to detect and track missile launches. The Pentagon selected several contractors to build the satellites, so the military is not reliant on a single company. The builders of the SDA’s operational satellites include York, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and L3Harris.

“We will increase coverage as we get the rest of those launches on orbit,” said Michael Eppolito, the SDA’s acting deputy director.

The satellites will connect with one another using inter-satellite laser links, creating a mesh network with sufficient range to provide regional communications, missile warning, and targeting coverage over the Western Pacific beginning in 2027. US Indo-Pacific Command, which oversees military operations in this region, is slated to become the first combatant command to take up use of the SDA’s satellite constellation.

This is not incidental. US officials see China as the nation’s primary strategic threat, and Indo-Pacific Command would be on the front lines of any future conflict between Chinese and US forces. The SDA has contracts in place for more than 270 second-generation, or Tranche 2, satellites, to further expand the network’s reach. There’s also a third generation in the works, but the Pentagon has paused part of the SDA’s Tranche 3 program to evaluate other architectures, including one offered by SpaceX.

Teaching tactical operators to use the new capabilities offered by the SDA’s satellite fleet could be just as challenging as building the network itself. To do this, the Pentagon plans to put soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines through “warfighter immersion” training beginning next year. This training will allow US forces to “get used to using space from this construct,” Sandhoo said.

“This is different than how it has been done in the past,” Sandhoo said. “This is the first time we’ll have a space layer actually fully integrated into our warfighting operations.”

The SDA’s satellite architecture is a harbinger for what’s to come with the Pentagon’s Golden Dome system, a missile-defense shield for the US homeland proposed by President Donald Trump in an executive order in January. Congress authorized a down payment on Golden Dome in July, the first piece of funding for what the White House says will cost $175 billion over the next three years.

Golden Dome, as currently envisioned, will require thousands of satellites in low-Earth orbit to track missile launches and space-based interceptors to attempt to shoot them down. The Trump administration hasn’t said how much of the shield might be deployed by the end of 2028, or what the entire system might eventually cost.

But the capabilities of the SDA’s satellites will lay the foundation for any regional or national missile-defense shield. Therefore, it seems likely that the military will incorporate the SDA network into Golden Dome, which, at least at first, is likely to consist of technologies already in space or nearing launch. Apart from the Space Development Agency’s architecture in low-Earth orbit (LEO), the Space Force was already developing a new generation of missile-warning satellites to replace aging platforms in geosynchronous orbit (GEO), plus a fleet of missile-warning satellites to fly at a midrange altitude between LEO and GEO.

Air Force Gen. Gregory Guillot, commander of US Northern Command, said in April that Golden Dome “for the first time integrates multiple layers into one system that allows us to detect, track, and defeat multiple types of threats that affect us in different domains.

“So, while a lot of the components and the requirements were there in the past, this is the first time that it’s all tied together in one system,” he said.

Pentagon begins deploying new satellite network to link sensors with shooters Read More »