Startup Roundup #3

Startup Roundups (#1, #2) look like they’re settling in as an annual tradition.

I’ve been catching up on queued roundups this week as the family was on vacation. I am back now but the weekly may be pushed to Friday as I dig out from the backlog.

There is a common theme to the vignettes offered across the years. The central perspective has not much changed.

I would summarize the perspective this way, first in brief and then with more words:

-

Founding SV-style startups or being an early employee is great alpha.

-

You create more value, and you capture more of that value.

-

Building real things that scale is so valuable that you can afford a lot of nonsense.

-

Venture capital similarly does foolish stuff a lot but the successes are so good that if they have good deal flow they still win.

-

Venture capitalists and others offering advice say many valuable things but also have their own best interests at heart, not yours, and will lie to you.

Or, with more words:

-

The central idea of founding or joining as an early employee of a startup, building something people want, raising venture capital funding in successive rounds and mostly adhering to Silicon Valley norms is an excellent one. If you have the opportunity to do YC you probably want to do that too.

-

Because you get equity you capture a vastly higher percentage of the value you create than you would if you worked for someone else. This is all a great way to change and improve the world, and also a great way to earn rather quite a lot of money. This is risky in the sense that most of the time your startup will fail, but failure is not so bad and you can try again in various ways. If you’re up for it, strongly consider doing it.

-

This works because the value in building real things that scale, at all, is orders of magnitude higher than the value of an ordinary job, plus you are capturing far more of it. The structure is hugely inefficient and wasteful and stupid and perverse in various ways, most of your activity is likely going to be built around assembling and selling the team and proving that it can Do The Thing, and learning how to Do The Thing, but it does result in attempting to Do The Thing at all, which is what matters. There is ‘a lot of ruin’ in this nation.

-

Venture capital returns, and especially the strong returns of the best VCs, are largely about selection and deal flow, and marketing themselves. The VCs tend to herd to an extent that it should challenge one’s overall epistemology and model of capitalism, and have similar flawed heuristics and are largely evaluating whether other VCs will be willing to fund in the future, and evaluating the team and its ability to pitch itself, and so on. Which again is hugely inefficient and wasteful and stupid and perverse compared to how it would ideally work, and it leaves a ton on the table, but it Does The Thing at all, so it beats out all the alternatives.

-

Venture capitalists will offer you lots of free advice, which as we know is seldom cheap. A lot of what they say is good advice, and you need to absorb their culture, but a lot of it is them talking their books and marketing themselves and the idea of doing a startup, or trying to get you to do what the VCs want to do for various reasons. Some of that will align with what is good for you. A lot of it won’t, and you have to keep in mind that when your interests are in conflict they are lying liars who lie, and at other times they fool themselves or don’t understand.

-

In particular, VCs and Paul Graham in particular will try to pretend that ‘what you do to succeed outside of fundraising’ and ‘how to set yourself up to fundraise’ are the same question, or have the same answer, and you should not think of this as a multi-part strategic problem. This is very obviously an adversarial message.

-

This type of adversarial message will happen one-to-many in general advice, and will also happen one-to-one when they talk to you. Listen, but also be on guard.

Here are some vignettes on this theme from the past year.

Emmett Shear offers advice on how to interpret advice from Paul Graham.

According to Emmett:

-

Filter his creative ideas, but pay attention, there’s gold in them hills.

-

If Paul tells you how a decision gets made, he’s often right even if he isn’t telling you the whole picture.

-

Paul’s advice is non-strategic, he’s saying what his model thinks you should do.

My reactions based on what I know, keeping in mind I’ve never met him:

-

Strongly agree, same as his public ideas.

-

Based on his public statements, I’d say he’s bringing you a part of the picture, often an important or neglected part, but he’s often being strategic in how it is presented and framed, and in particular by the selection effect of when to explain what parts, and what parts to leave out.

-

I strongly believe many Paul Graham statements in public are strategic. I also think Paul’s model in many places is at least partially strategically motivated. Even if his motivation in the moment is non-strategic, the process that led to Paul having that opinion was, de facto, strategic.

-

I can believe that Paul’s private advice is mostly non-strategic beyond that.

-

Given the overall skill and knowledge levels, with that level of trustworthiness, that’s still an amazingly great source of information. One of the best. Use it if you have access to it.

One common pattern of advice from Paul Graham has been talking up the UK.

Rohit: This is a pretty remarkable tweet, and a sign of the times.

Paul Graham (April 15, 2025): A smart foreign-born undergrad at a US university asked me if he should go to the UK to start his startup because of the random deportations here. I said that while the median startup wasn’t taking things to this extreme yet, it would be an advantage in recruiting.

What an interesting twist of history it would be if the UK became a hub of intellectual refugees the way the US itself did in the 1930s and 40s. It wouldn’t take much more than what’s already happening.

It has lower GDP per capita, but it also has rule of law.

G: what if it was Europe instead of the UK? would you still recommend?

Paul Graham: It’s the same tradeoff, yes.

Graham agrees the regulatory burdens of being in Europe are extreme, so for now he sees a mixed strategy as appropriate. Those who are worried about being in America can be recruited to the UK or Europe, which justifies (in his mind) more UK-or-Europe-based startups than we currently have.

Paul Graham is the best case scenario. When you see advice from other venture capitalists, assume they are less informed and skilled, and also more self-interested, until proven otherwise.

Zain Rizavi: wild that it only took 4 months of building to realize I’d take back nearly every piece of “advice” I gave founders over 4.5 years investing. Most VC advice is cosplay

Martin Casado: yup

Martin Casado has been on an absolute ‘saying the quiet part out loud’ tear recently. No matter how vile and bad faith I find his statements about AI policy and existential risk and everything surrounding effective altruism and so on, he’s got the Trump-style honest liar thing going especially on the venture side, and yes it is refreshing.

Never conflate the medium and the message, or the map and the territory, or the margin and the limit.

I don’t think Paul is being naive here.

I think he is doing a combination of thinking on the margin and talking his book:

Paul Graham: Figuring out what a startup should say to investors is strangely useful for figuring out what it should actually do. Most people treat these questions as separate, but ideally they converge. If you can cook up a plausible plan to become huge, you should go ahead and do it.

For example, I’m always looking for ways to add network effects to a startup’s idea. Investors love those. But network effects are genuinely good to have. So any we come up with in order to feed to investors, they should probably go and make happen.

Experienced investors are pretty rational. But those are the ones you want anyway.

Should you be thinking big, and about what scales, and taking big swings? Absolutely, although the VCs want you to do it more than you should want to do it due to different incentives.

On the margin, founders benefit from VCs pushing founders to do more of the things that VCs want to hear, as a lot of why they want to hear them is that those actions correlate with big success. The danger is when you are not on the margin, and stop being grounded in reality and start to believe your own hype and stories.

If you have the option to do YC, rest assured that as long as you’re not collapsing a huge bunch of SAFEs the valuation boost from YC’s reputation is worth vastly more than the share of your company YC takes. You’ll be net ahead on cash and equity very quickly.

Matt Levine has often mentioned how valuable it can be to not have to mark your investments to market. Early stage VCs are experts at controlling how and when their investments are marked to different numbers.

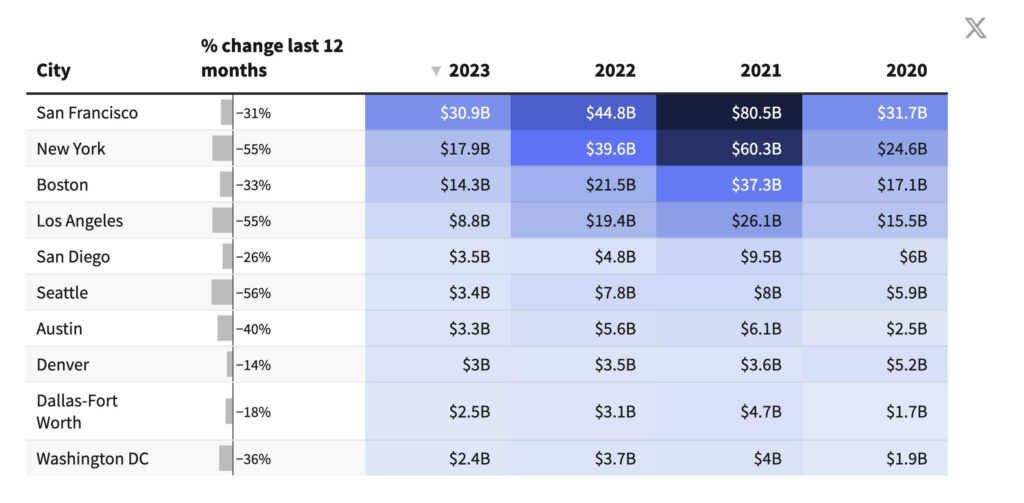

Joe Weisenthal (April 21, 2025): Blackstone is now down 40% from its November highs, and is right back at its post-Liberation Day lows. Remember, this is probably the best run manager of private assets in the world, so just consider how your run of the mill PE or VC shop is looking right now.

Paul Graham: Early stage VCs are presumably looking better, because an early stage investment in a startup is mostly a bet on whether the founders are Larry & Sergey or not, and that is independent of global political and financial trends.

Joe Weisenthal: Sure, but that only pertains to an individual bet, not the entire asset class, right?

Paul Graham: You mean the value of a sufficiently large number of such bets should vary with the market’s expectations about future growth? In theory yes. But in practice not so much.

In practice the effects on early stage valuation are muted by (a) the fact that big exits, where all the returns are, will be 10 years in the future or more, and (b) the dynamics of fundraising; there’s no such thing as value investing at the seed stage.

There are certainly ups and downs in early stage startup valuations, but they’re driven mostly by variations in how excited investors are about startups. E.g. valuations are high now because investors are (justifiably in my opinion) excited about AI.

Mr. Plumpkin: Not how math works sorry. The difference between them building a $1T company and a $2T company due to market valuations still impacts the option math today.

Paul Graham: Only by 2x, whereas great vs ok founders can increase the outcome by 1000x or more.

Yes, that would be only by 2x, but that’s a 50% markdown.

This is purely not marking to market and strategic ignorance about market prices. It is price fixing by a VC cabal via norms. It is a conspiracy in restraint of trade and collective fiction.

Sure, the best founders might increase value by 1000x, but the best founders under bad conditions are then worth 500x of what the bad founders were worth under good conditions, rather than 1000x. Still counts.

What Paul Graham is effectively saying here is that VCs are a conspiracy in restraint of trade, that (among other things) refuses to pay fair prices for top startups, instead setting what are effectively highly constrained norm-based prices to avoid the best founders charging what they are worth, so top VCs can bid with reputations and connections and capture that surplus rather than bidding against each other with dollars.

I do believe this is true. The top VCs are in collusion to bid with reputation and services and connections and future promises rather than with dollars, such that the top investments are both obvious to most VCs and also vastly cheaper than their expected value. And they persuade the founders involved that this is good, actually, because of things like worries about a down round.

Graham himself has noted that the difference in price for the best startups is dwarfed by how much better their prospects are, that the smart VC mostly ignores price. That indicates the prices for the good prospects are way too low.

Whereas if a top founder actually got what they were on average worth, VCs who invest would be unsure if they were getting a great deal.

Why should the VCs get that deep discount to actual value, despite the fact that if the founder insisted plenty of those same VCs would pay up happily? Because they tell a story that the company isn’t entitled?

And if you can get away with that, then yeah, who cares if the exit value is down by half, I guess? It doesn’t change any of the norm-based prices? And for worse founders, instead of the prices dropping so the market clears, a few survive and lot of those deals die.

One of the best reasons to distrust VCs is that they make a lot of arguments that you should beware when they give you ‘too good’ a deal, including but not limited to them paying more money to get less, and instead you should give away additional large stakes in your company or other things specifically in order to ensure the vibes remain good and you can tell a story to future other VCs.

As in, because you might have to raise at a lower number in the future, you should raise at a lower number than that now, so you don’t have a ‘down round.’ Or because you couldn’t handle having the cash.

I do agree that ‘down rounds’ can kill companies and that is bad, but come on.

Paul Graham: Believe it or not, it’s dangerous for a startup to raise too much at too high a valuation. This sounds like a good problem to have, but it isn’t. Both make your next round harder.

Raising too much makes you spend too much, which makes it harder to reach profitability. And a high valuation makes it harder for the next round to be an up round, which both investors and founders prefer.

Why do founders raise too much at too high a valuation? Because most VCs want to own a large percentage of the company. They’re less price sensitive though. They’re willing to spend a lot to get it. So the result of these constraints is: large investment at a high valuation.

That last paragraph is a partial answer to an importantly different question: ‘Why are founders sometimes ABLE to raise so much money, at such a high valuation, that it becomes difficult to have an ‘up round’ next?’

Yes, the answer is that VCs are ‘not price sensitive’ when deciding to invest (there are limits, eventually, of course, at least one hopes), they are ‘vibe sensitive’ to whether it all feels right and how it would look. And they have heuristics that say, if the deal is great, you do not care about the price, the real danger is missing out. The ultimate case of FOMO. So in many cases you can kind of ‘name your price.’

It is also a hell of a thing to frame getting a great deal that way.

The second paragraph points to the real danger. You cannot afford to let what happened go to your head. You cannot afford to then spend money like you are actually worth what the VCs paid, and that you will soon be able to raise more at an even higher number.

Instead, you need to do something rarely done, which is to understand that the number was ‘too high’ and that you might face a down round.

You know what I’ve never heard of being done? A founder CEO says, after a round, ‘these VCs went completely crazy bidding against each other. We raised $20m at a $100m valuation, and realistically it should have been less than half of that. We made damn sure the terms were airtight, so we can safety do a down round if needed, and we are setting aside the extra money so we don’t go too big or spend too much, and we’re setting your options deals accordingly.’

This also makes good trading sense. Most startups have high failure risk at each step, so if you survive you should be worth more. But if you’re the ‘super hot’ startup, in a great spot, the chance of (unrecoverable) failure in the short term could be quite low. If you do great, you’ll gain tons of value. So if you do only okay, it seems perfectly fine to say the expected value is modestly down from before.

There is the danger that you overspend, grow too big, your burn rate skyrockets, your focus is lost and so on, if you’re not careful. So… don’t do that? I know, easier said than done, but not as hard as they make it sound.

Convincing founders they should give up 10% of their company so that the round isn’t technically ‘down’ is one of the great cons of history. One can also call it an illegal conspiracy in restraint of trade.

Europe in general and Germany in particular have long been doing a natural experiment to see how annoying and expensive you can make startups before you kill them entirely. The answer is quite a lot.

Nathan Benaich: 12 hours and counting – notary reads every single word of Series A docs in Germany out loud in front of founders. In person. Guys, we have GDP to grow here. Pure prehistoric madness.

Paul Graham: We can use this practice as a canary in the coal mine to measure whether Germany is serious about startups. As long as it persists, they’re not.

Ian Hogarth: The most significant cost of the Germany notary system is how much friction it introduces for small investors ie angel investors. Always created a higher hurdle for me to angel invest in German start-ups/or introduce angel investors.

Henry de Zoete: 100% – same for me. It’s not worth the hassle for angel investors

Alex MacDonald: I once had to physically go to the German consulate in London in order to get a document ‘apostilled’ to complete an angel investment.

Never invested in another German company after that. 🫡

A fun story about correlation and causation.

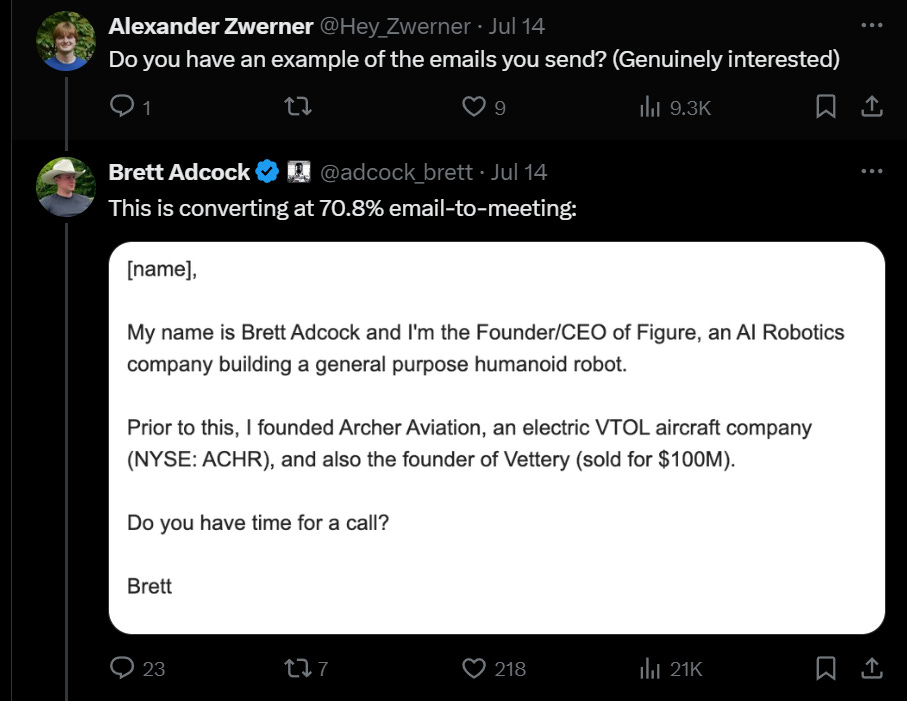

Trevor Blackwell: How to be a top VC with one simple trick:

Auren Hoffman: one of the firms we invested in recently raised their Series A. To start the process, the company sent emails to many VCs. stats on raise:

The top branded partners at the top branded firms: almost all responded to the email within 4 hours. All wanted to set up a meeting within a day.

The top branded partners at the mid-tier firms: usually needed to receive 2 emails to set up a mtg. Mostly requested mtgs within 4 days of 2nd email.

The low-tier firms: had the lowest response rate. Many times they wanted to set up a mtg 2-3 weeks out. They all missed seeing the deal.

I’m surprised that the top-tier firms are more responsive than the low-tier firms but kinda makes sense. Always be hustling.

I do think responding quickly is the best play whenever possible. But consider that the firms might be responding more optimally than you might think.

Say you’re at a low-tier firm. If you take the meeting tomorrow, and they give you that meeting, and you love it, and it closes next week, guess what?

You still probably didn’t make the round, because the startup has better options and turns down your money. In a different world you’d be able to compete on price, but that’s not how this works, so you lose. Good day, sir.

By scheduling two weeks out, you’re saving everyone time – that’s the point at which the round is likely actually available and so the meeting is worthwhile.

That’s not to discount that hustle and fast response also make a difference, but in general if you see a contrast this stark there’s an actually good reason for it.

Whereas if you are a top firm, your entire job is to quickly find the best offers like this, and lock them down before the mid-tier firms or ideally even your top-tier competitors can do an evaluation and try to box you out. You have to hustle.

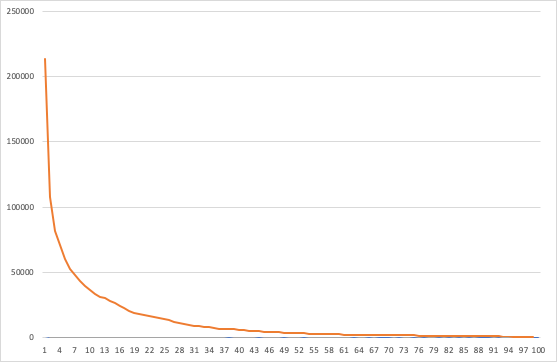

The question is why anyone puts their money in, it’s obvious why you would want to do the job with other people’s money:

Sam Altman asks a good question: this is much less important than tweeting about agi, but it is nevertheless amazing to me that the entire venture industry can (in aggregate) lose money for so long and keep getting funded.

I am very curious why LPs do it.

(obviously if you can fund the top funds you should!)

My hunch is that a lot of this is people not understanding adverse selection. They don’t get how much those top funds are cherry picking the best deals, and how much this leaves everyone else in VC at a severe disadvantage. And more of that is thinking that oh, I’m smarter or I’ve found the smart one, we will make it work, or people simply not realizing that ‘non-elite’ VCs on net lose. Or simply wanting to be part of the action.

Another explanation is that this is not accounting for the potential future elite premiums you might be able to collect. So you invest now at an economic loss, to try and gain a reputation later that would let you extract rents.

Part of the story is almost surely that those involved don’t believe or understand that the industry overall loses money.

And part of the story has to be that investors want in on the action, it is a status marker, it is fun, it provides inside information and connections and so on.

How to come up with your next great startup idea, according to YC?

It starts with not demanding too great a startup idea? There’s a list and also a video.

Jared Friedman, YC Partner: How to Get Startup Ideas

Common mistakes:

Waiting for a “brilliant” idea

Jumping into the first idea without critical thought

Starting with a solution instead of a problem

Believing startup ideas are hard to find

I agree with the first two. You shouldn’t ‘wait’ for a brilliant idea, but neither should you settle for one that is not great. It’s more that the great ideas often won’t ‘feel brilliant.’

The third is more interesting. I half buy it. Certainly ‘solution in search of a problem’ is an issue, but problems are a dime a dozen even more than startup ideas. Good solutions are not, and can be the relatively scarce resource.

The theory here, as I understand it, is that the way to get to a solution that solves a problem people will pay to solve is to solve a problem. YC especially preaches to look for a solution to your own problems, a ‘fine I will solve this myself just for me’ idea. That can of course still not be a market fit at all (see MetaMed), but you have a shot.

Whereas if you have a solution in search of a problem, you’ll invent some story of why your solution is useful, but you won’t have product-market fit. I buy that this is a common trap, and plausibly one of the key things that went wrong at MetaMed.

If you do have a solution in search of a problem, it is definitely worth doing a search for problems that it solves, so long as if you don’t find a good one you then give up.

The fourth is another ‘yes and no,’ finding any idea at all is easy, finding the best ones is hard, and is especially hard if you are not someone with lots of relevant connections and experience.

Evaluate your idea on four criteria, take the average of the scores:

1. Potential market size

2. Founder/market fit

3. Certainty of solving a big problem

4. Having a new, important insight

This seems like one of those ‘these things should not be equal weight’ situations, even if they are the top four criteria. At minimum the average should be more like… the product? These are all failure points, not success points.

Positive signs for good ideas:

Making something you personally want

Recently became possible due to changes

Successful similar companies exist

As usual there is the conflict, if it wasn’t possible before how do similar companies exist? So you need to get the details right on what those mean.

I’ve grown more skeptical of ‘only possible recently’ as being too important. Certainly it helps that ‘without AI from this year this wouldn’t work’ but also… people don’t do things. Ideas just sit there. Yes, most good Magic: the Gathering decks involve something you couldn’t do until very recently, but also there was a Pro Tour where Trix (which went on to completely dominate the same format) was legal and no one had it.

Generating ideas organically

Learn to notice good ideas

Become an expert in a valuable field

Work at the forefront of an industry or at a startup

The first two feel like ‘marginal’ advice. As in, true on the margin, but not overall.

Seven recipes for generating ideas (in order of effectiveness):

Start with your team’s unique strengths

Think of things you wish someone would build for you

Consider long-term passions (with caution)

Look for recent changes enabling new possibilities

Find new variants of recent successful companies

Crowdsource ideas by talking to people

Look for broken industries to disrupt

Sure, that all makes sense.

Best practices:

Allow ideas to morph over time

Start with a problem, not a solution

Think critically about ideas for a few weeks

Be open to ideas with existing competitors

Standard stuff here. Mostly, yeah, I agree.

A culture that cannot criticize itself cannot fix its mistakes.

Antonio Garcia Martinez: One of the Great Necessary Delusions of Tech is:

You can’t make fun of anyone who’s actually doing or building.

Even though you know it’s dumb or a grift.

It’s like a stock market with no short-selling: Feels more noble, but really, it’s just bad for price discovery.

Thought while reading one of those “we’re shutting down” threads where something that seemed dumb from day one is buried and eulogized like a juvenile cancer patient, while every reply-guy mourns appropriately.

Sure, I’d rather live in this world than a cynical one–it’s net good, to be clear–but heavens to Betsy is it all a bit much at times.

Camilo Acosta: As founders, we have the privilege and duty to call these people out — and should, because it benefits the ecosystem overall when it is done. When it doesn’t happen it sets back the founder community (see: Theranos).

If Silicon Valley is to take its rightful place as a true part of Nate Silver’s The River, or simply it wants to make good decisions, this requires a desire to understand the world and be accurate. Short selling needs to exist, at minimum rhetorically. Instead, they have largely hooked their wagon to a combination of enforced optimism, consensus zeightgeisting and collaborative vibe warfare. They think this is good for them, and that tells you a lot about who they are and what to expect from them and how to evaluate their claims.

Anton: startups illustrate something like Amdahl’s Law for suffering – if you are say, top 10% in being able to bear e.g working 14 hour days for months or years, 90% of your actual suffering in building a company is going to come from the places where you aren’t as resilient.

If you love writing code but hate answering email, 90% of the reason building a company will suck for you is the email. if you love talking to users and can do it all day, but hate operational minutia, most of your suffering will come from the minutia.

A startup does not offer you the luxury of choosing which things to do versus not do. You have to do all of it. Which means you are doing whichever part you think sucks.

A lot of what you are being paid for it the willingness and ability to do that.

Ashlee Vance: VC the other day told me, “We’ve lost several really good founders to ayahuasca. They came back and just didn’t care about much anymore.”

Austen Allred: Of the Silicon Valley founders I know who went on some of the psychedelic self-discovery trips, almost 100% quit their jobs as CEO within a year. Could be random anecdotes, but be careful with that stuff.

[Sample size is 8. Of which he thinks 4 are happier.]

A huge percentage of the time that I hear about someone trying Ayahuasca, it results in them royally screwing up their life, sometimes irrevocably. This is true for public stories and also for private stories. Even when that doesn’t happen, the experiences seem to usually have been pretty miserable, without much positive change afterwards.

By all accounts this is a no-good-very-bad drug. Avoid.

Discussion about this post

Startup Roundup #3 Read More »