In honor of the latest (always deeply, deeply unpopular) attempts to destroy tracking and gifted and talented programs, and other attempts to get children to actually learn things, I thought it a good time to compile a number of related items.

Gifted programs and educational tracking are also super duper popular, it is remarkably absurd that our political process cannot prevent these programs from being destroyed.

As in things like this keep happening:

NY Post: Seattle Public Schools shuts down gifted and talented program for being oversaturated with white and asian students.

Once again, now, we face that threat in my home of New York City. The Democratic nominee for New York City Mayor is opposed to gifted and talented programs, and wants to destroy them. Yet few people seem to have much noticed, or decided to much care. Once people realize the danger it may well be too late.

To state the obvious, if you group children by ability in each subject rather than age, they learn better. Yes, there are logistical concerns, but the benefits are immense. Gifted programs are great but mostly seem like a patch to the fact that we are so obsessed with everyone in the room being in the same ‘grade’ at all times.

I agree with Tracing Woods that ‘teaches each according to their ability’ is the bare minimum before I will believe that your institution is making a real attempt to educate children.

Tracing Woods: A good example of the absurdity of “grade-level” thinking, from Texas: “If they’re reading on a second-grade level, but they’re in the third grade, they’re always going to receive that third-grade instruction.”

This makes no sense. Learning does not simply follow age.

Imagine having a “grade level” in chess. 9-year-olds in the third grade advancing to play against 1100 elo players. 100 more elo per year.

“Grade-level performance” has always been nonsensical. Learning does not work that way. Just figure out what people actually know and need

Danielle Fong: sooner or later, and probably sooner, all this will be thrown out in favor of an adaptive learning environment, the human teachers and other students can give individual attention when you’re stuck, and you can maxx out learning like a game. already happening privately. +2sd

Eowyn Jackman: I know I’m supposed to move on but I don’t think I can ever forgive the US public primary education complex for testing me and saying he “has a college reading level” at 9 years old but not administering an exam for me to be in the “gifted/advanced” classes at my PWI until two years later when I wrote my first book. So much time wasted.

Would’ve loved to have an office, secretarial job before 15 tbch

Wow I need therapy 😅

James Miller: Imagine math classes grouped by ability, not age. You’d have classes with 7- and 17-year-olds together.

Tracing Woods: And that’s a good thing (No, but seriously, at that point put them in different schools)

I bite the bullet. I do think it’s fine and actively good to have 7-year-olds and 17-year-olds in the same math classroom.

Of course, if you think that learning is bad, you won’t like this plan to have kids learn.

Owen Cyclops: this conception of early childhood education poses a generally unasked question to our present educational paradigm, which is: what could be the potential downside of learning things too quickly? from my perspective, this is basically never asked. its a total 100% blind spot.

[this is part of a long thread complaining about how awful it is if kids were to learn things too quickly, before they are supposed to, because ‘stages of development’]

Thomas: The main downside brought up re: “learning too quickly” is being ahead of peers. There’s parents’ posts online sharing experiences of being told not to read to their kid at home, or not teach them new math concepts.

Divia: Fwiw I hear people talk about the downside of learning too fast constantly! And have since I was a kid. Mostly whenever anyone wanted academics to be faster than it was convenient for someone they would talk about the downsides IME.

The ‘learning too much too soon is bad’ paradigm seems categorically insane. Here’s the concrete example Owen gives:

Owen: i’m in the forest (this actually happened). a kid asks: why is this log making a sound when i hit it with a stick? and this adult says, “well, the molecules in the log vibrate when you hit it, because you hitting it transfers energy into the log. you’re hearing the vibrations.”

the kid is NOT at that developmental stage (in my opinion). even if they can understand this (may be impossible, they might just be repeating what you’re saying), that type of understanding comes later. that is not the developmental stage a five year old is at. not their world.

I mean, maybe they have enough physics that this is the right explanation. Maybe they don’t, and it would be modestly better to simplify it a bit. But then they can ask.

This seems fine, and opening the doors to ‘what’s a molecule?’ or other similar questions seems great. They ask, you tell them. The actual objection here is ‘you need to explain [A] then [B] then [C]’ and I think that is usually vastly overstated but okay, sure, that doesn’t tell you what age you should tell people [C].

At some point, if you’re far enough ahead or behind the class, the class is worthless to you. A remarkable number of students hit this threshold, or would hit it if they weren’t being sabotaged to not hit it.

There is a point of diminishing returns for sufficiently young students, where you start to outstrip your ability to efficiently process the information and learn the material at your current age, but many students are very far away from that limit. As of course they are, if they’re forced to proceed at the speed of the typical subpar ship, which shall we say is not close to even that ship’s maximum speed.

Tracing Woodgrains: The most refreshing and novel thing to me about the Alpha/GT School model is the four hours of extracurricular workshops.

In sixth grade, I did online school. Completed the entire seventh and eighth grade curriculum in two hours a day that year. And then with all my extra time, I played video games.

Much healthier to have an institution that recognizes what can really be done with all of that time.

Patrick McKenzie: While this makes me feel *extremelyold, my recollection of 4th-8th grade was a solid 1.5-2 years of instruction and 3 years of being physically present while classroom management was conducted.

If you object to being physically present for classroom management you will become one of the focuses of classroom management, so I spent a lot of time counting ceiling tiles, drawing cubes, and writing out the solutions for all possible games of 24.

Ryan Moulton: I think you can get 80% of the benefit of ~whatever gifted/tracking/etc. program in gradeschool by having any mechanism at all to let self directed kids be self directed.

“You already know this, so just go do Khan Academy for an hour during math time” is an essentially zero cost intervention.

“If you finish your grammar/spelling/vocab sheet early, you are allowed to read your library book” is too.

Teachers don’t reliably do this, because letting kids do different things sometimes creates conflict in class. If they did reliably do this then most of the debate about how to organize gradeschool among kids of different academic ability levels goes away.

When you stop holding kids back, you instead get things like in this thread: The 11 year old boy in Organic Chemistry that goes on to be a researcher, the girl graduating college at that same age. Which is proof by counterexample that all this ‘not ready’ nonsense is indeed nonsense.

An important aspect of denying the reality of different learning abilities is that it is absurdly cruel to those you are gaslighting – they are told that they are just as smart and good at learning as everyone else, so what are they to think about their failure to get those same results?

Anonymous: We have this myth of a ‘fast learner’ but research suggests people actually learn at similar rates. A ‘fast learner’ is really just someone who’s been exposed to this problem/material before, maybe multiple times. People seeing something for the first time will struggle.

Eigenrobot: there’s something cruel about asserting that people dont differ in ability like. its cruel to directly rub it in someones face, but its also cruel to proactively lie to people when, be real, they either know youre lying or will end up damaged by believing you.

Some may say “maybe but acknowledging difference in ability is bad because the moral value is a function of their ability and we don’t want a norm of believing that some people are worthless” and to them i say find god.

What happened with No Child Left Behind? One of its architects explains that they knew you can’t actually leave no child behind. That’s impossible. You obviously have to leave some children behind. They were declaring a goal of none with the plan to modifying it to some. Then they met Congress, which has become unable to do reasonable things, so instead of the usual ‘quietly change the rules and declare victory’ the insane requirements stayed on the books and everything went to hell trying to work around them. Whoops.

The good news is that now everyone knows that Congress is unable to fix broken things, so we can correctly plan that laws will stay on the books indefinitely exactly as written no matter how broken they get, and write them accordingly. I endorse both the fully serious and sarcastic versions of that sentence.

Reading is a godsend. The earlier your kids can read, the better, on so many levels. One that is vastly underestimated is this makes parenting vastly easier, you’ve unlocked unlimited cheap, healthy and non-disruptive education and entertainment. It unlocks all the things.

Erik Hoel here says that with a year of dedicated effort, he got his 3-year-old to read at 9-year-old levels, and offers a guide: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3. The core is simple, phonics plus spaced repetition plus books as the center of entertainment. In my experience, you need to push to the critical point where they can largely teach themselves via more reading plus a little adult help (and AI voice help?) and then you are home free.

Eric seems to have focused entirely on reading first and ignored other subjects, including math, while he was doing that. This actually seems exactly right to me, if you can (as he did) get your child to buy in, because reading unlocks all the things and builds on itself. Get to that critical point first, worry about everything else (that isn’t a short term practical need) later.

A woman virtuously notices she is confused about why mirrors work the way they do and asks, essentially, ‘mirrors how do they even work,’ as opposed to most other people who have no idea how mirrors work the way they do. That’s great, thumbs up.

Then this gets quoted with ‘this is why we need the department of education,’ but no, actually we had a department of education and not only does no one know no one asks the question. This is why you don’t need the department of education. You need an LLM, and you need to teach people to be curious and give them actual education.

We all know it works. So why don’t schools use it?

Eric Hoel: “The power of spaced repetition has been known for 150 years. It replicates and has large effects. So why is spaced repetition (or even its more implementable form of spiral learning) not used all the time in classrooms? No one knows!”

Spaced repetition works so well that it ends up causing me to memorize a lot of spoilers that I actively don’t want to remember. As in, I’ll keep trying not to think of the pink elephant, to remind myself to forget, at increasingly long intervals, which cause me to remember, and whoops. Damn it. One could use this power for good.

Paper suggests new way to teach economics nonlinearly, supposedly so it will line up with how people learn. I think this is essentially ‘include spaced repetition in your lecture plan.’ Which is one of those obviously good ideas that no one implements.

bosco: 4yo is probably ready to memorize her address, and at least one phone number, in case of emergencies, but she is completely uninterested when I try to teach her the spiel any tips?

Niels Hoven: If you’re having trouble getting your kid to remember your phone number, make it the password to your iPad’s lock screen and watch how quickly they memorize it

Kelsey Piper: We’ve been encouraging the eight year old to pick up some history by saying to one another in front of her “oh, the switch passcode is the year of the Marco Polo bridge incident” or “yeah I changed it to the year Constantinople was sacked in the Fourth Crusade.”

It seems like something you could study and measure, but it seems no one has?

Pamela Hobart: why do so few people have any real insight into just how *verydisruptive interruptions are?

I’m not even sure ‘learning time lost’ is the right measure, as time is not created equal, and there are different types of learning, some of which are far more disruptable than others, so this can shift learning composition, likely in ways we do not want.

Ben Hsieh: Parents will likely say, “Drills and rote memorization? That pales in comparison to my strategy, instilling a lifelong love of learning,” and then not instill a lifelong love of learning.

Drills and rote memorization are not ideal, but they work. If you can do better, great, but way too many parents and schools think they can do better and are wrong.

Autumn: if as a society we value math-based disciplines so much, can i ask why we teach calculus in a way thats optimized to weed out students who wont comply with hazing. why do we design them to teach horrible habits for later studies in math?

Sarah Constantin: this is a pet peeve of mine.

there are people who want to make classes easier & less advanced (e.g. not teaching calculus in high school) and there are people who want to scout for exceptional talent but there’s very few people pushing for actually teaching the material well!

“let’s try to make sure everyone in this calculus class learns calculus” is a very lonely mission, even though IMO it’s common sense.

In general we have the problem of teaching math in ways that make many students hate math. I don’t think this is especially a problem in calculus, at least the way I learned it (in a high school class)? Autumn suggests the college method is somehow worse.

Obviously ‘won’t comply with hazing’ is a terrible reason to drive someone away, calculus is vital to understanding the world (for intuition and general understanding, not for actually Doing Calculus, I actively do a happy dance every time I get do Do Calculus which is very rare) and at minimum we want everyone who takes such a class to learn calculus.

However, in terms of the math-based disciplines, as long as we are gating on actual ability I think weeding people out here is in principle fine? In the sense that if you design a good filter, you’re doing a favor for those you filter out, except that now they don’t get to understand calculus.

I strongly agree with this. It is very obvious interacting with kids that they yearn for meaningful work in the ordinary sense of work

Ozy Brennan: my pet parenting theories:

Children yearn for meaningful work; child labor is bad but we’ve overcorrected.

Whenever possible, children should be brought along to adult activities instead of adults going to child activities.

tips for bringing kids along to adult activities: bring a Kindle or (in extreme situations) a laptop. explain behavioral norms ahead of time. allow independence. have friends who like kids. prioritize activities you and kids both like (museums, movies, parks, whatever).

Putting children to pointless industrial work is not a good idea. But if they can understand why what they are doing is useful, yeah, they really dig it, and it seems obviously great for them and also great for you.

For trips, you have to calibrate to your particular kids, but yes, absolutely, especially once the kids cross the ‘can be entertained by a book’ threshold.

Patrick Collison: In which domains are elite practitioners celebrating the kids being better than ever before? Would love to read about a few instances. (Not just where there’s one particular genius, such as Ashwin Sah’s recent success, but where “the kids” as some kind of aggregate appear to be improving.)

Michael Nielsen: It was perhaps in my third week of linear algebra (MP 174!) that the professor told me that incoming students were noticeably worse at math than they used to be There are a very large number of potential confounders here. The point, of course: that was ~30 years ago. “Back when I was a boy…” nostalgia seems to be time-invariant.

I’ll state my prejudice, backed by a wide smattering of anecdotes, and not much else: the top 0.1% today are vastly more competent across a much wider range of subjects than 20 years ago. And that same statement was also true 20 years ago. And 40 years ago. And 60 years ago…

(I don’t mean that a given individual is more competent in every domain. But the ceiling per-domain will be higher, and the range of domains much broader.)

For comparison, the 1939 Putnam, where (IIRC) Feynman was Putnam Fellow. And the 2023 Putnam. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather take the first.

Charles: I think the answer to this is “all of them” or close to it. The very best teenagers at almost every endeavor are better than they’ve ever been.

It’s below the 90th percentile (maybe even higher) where it’s a different story.

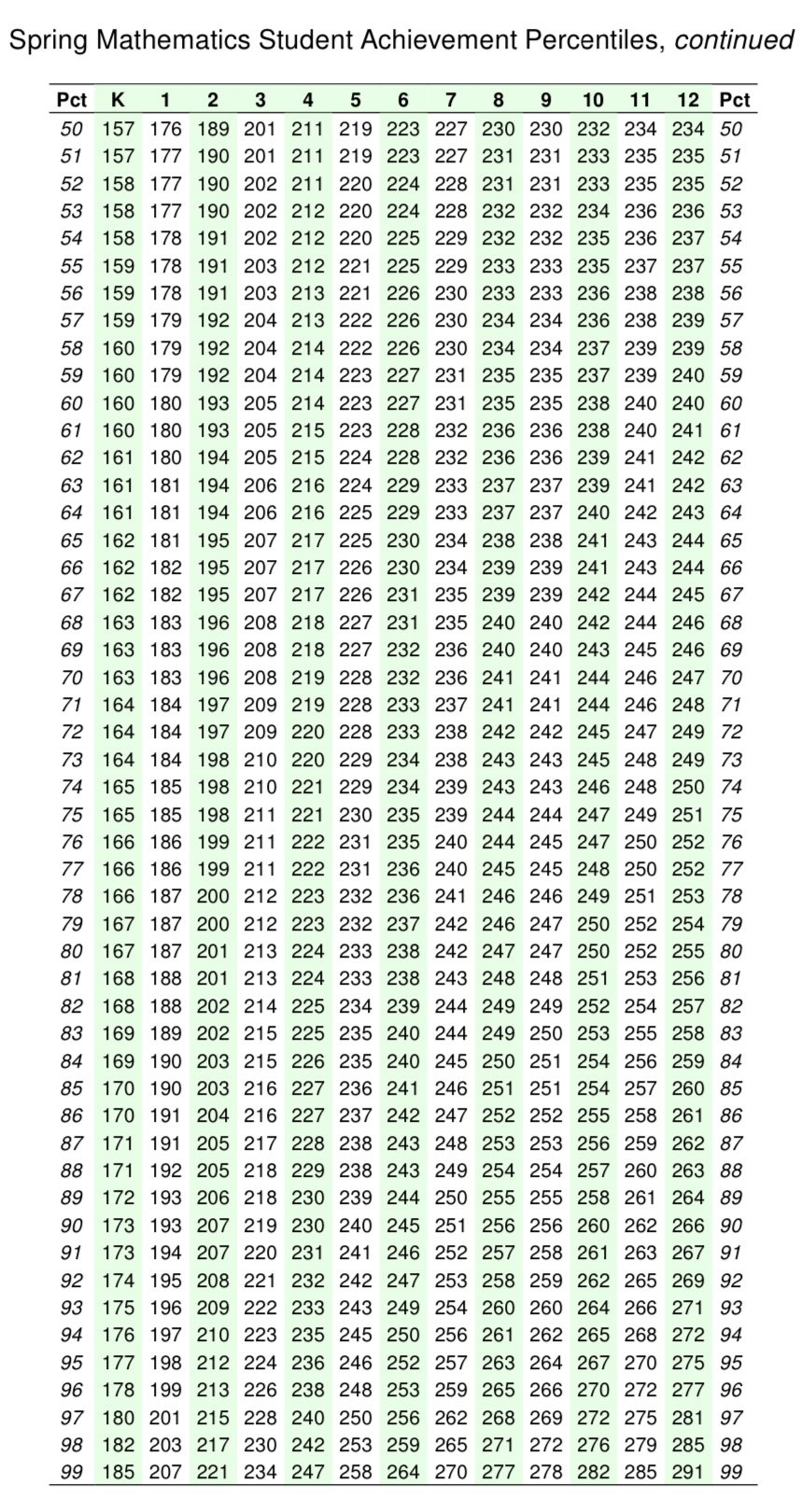

Is are children learning? In high school math, the answer seems to be no. The 50th percentile student gets a 230 in 8th grade on this test, and then a 234 in 12th (a second source said 232→237, but that’s the same thing), and we know from the higher percentiles that the test is not being saturated here. Note that reading scores only increased 5 points, from 224→229.

The obvious question is, if students are learning this little, why are we wasting their childhoods in school at all? It seems like there is no point. One would think that at least this much improvement would happen via osmosis and practical learning.

Paul Graham: 13 yo asked me to teach him how to write essays. I asked if he wanted to learn how to write real essays, or the kind you have to write in school. He said the school kind, because he’s writing one for school.

I don’t mind if my kids have to learn math that’s not real math or writing that’s not real writing or science that’s just words, but at the same time as I teach them these things I always try to give them an idea of how they’re fake, and what the real version is like.

At least 13 yo won’t spend years puzzling over how the “conclusion” is supposed to be different from the “introduction” even though they’re saying the same things. I told him upfront it’s just an artifact of this fake format.

RashLabs: How does one write a good essay for school?

Paul Graham: You just write a good essay. But your teachers may freak out if you do.

Patrick McKenzie: Good essays disrupt the production function of teachers w/r/t essay grading/correction. Some teachers give some students a bit of leeway to take more of their cycles than generally required, some of the time.

I once wrote an essay about how the hamburger essay format (buns on top and bottom, three layers in middle) was artificial, limiting, and unengaging, and got a talking to which was… at least minimally helpful.

There are some skills, especially more basic things like spelling and grammar, where the two types of good line up. Being able to write a good School Essay does give you a leg up on a Real Essay, if you don’t get trapped in the arbitrary parts of the format. But past a certain point, they are very different skills.

Paul is nailing the key point. Which is, if a child must write a School Essay, it is vital not to gaslight them about what they are writing, or pretend it has much to do with a Real Essay. Never pretend the fake thing is not fake.