Last week, a prominent US senator called on the Federal Trade Commission to investigate Microsoft for cybersecurity negligence over the role it played last year in health giant Ascension’s ransomware breach, which caused life-threatening disruptions at 140 hospitals and put the medical records of 5.6 million patients into the hands of the attackers. Lost in the focus on Microsoft was something as, or more, urgent: never-before-revealed details that now invite scrutiny of Ascension’s own security failings.

In a letter sent last week to FTC Chairman Andrew Ferguson, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said an investigation by his office determined that the hack began in February 2024 with the infection of a contractor’s laptop after they downloaded malware from a link returned by Microsoft’s Bing search engine. The attackers then pivoted from the contractor device to Ascension’s most valuable network asset: the Windows Active Directory, a tool administrators use to create and delete user accounts and manage system privileges to them. Obtaining control of the Active Directory is tantamount to obtaining a master key that will open any door in a restricted building.

Wyden blasted Microsoft for its continued support of its three-decades-old implementation of the Kerberos authentication protocol that uses an insecure cipher and, as the senator noted, exposes customers to precisely the type of breach Ascension suffered. Although modern versions of Active Directory by default will use a more secure authentication mechanism, it will by default fall back to the weaker one in the event a device on the network—including one that has been infected with malware—sends an authentication request that uses it. That enabled the attackers to perform Kerberoasting, a form of attack that Wyden said the attackers used to pivot from the contractor laptop directly to the crown jewel of Ascension’s network security.

A researcher asks: “Why?”

Left out of Wyden’s letter—and in social media posts that discussed it—was any scrutiny of Ascension’s role in the breach, which, based on Wyden’s account, was considerable. Chief among the suspected security lapses is a weak password. By definition, Kerberoasting attacks work only when a password is weak enough to be cracked, raising questions about the strength of the one the Ascension ransomware attackers compromised.

“Fundamentally, the issue that leads to Kerberoasting is bad passwords,” Tim Medin, the researcher who coined the term Kerberoasting, said in an interview. “Even at 10 characters, a random password would be infeasible to crack. This leads me to believe the password wasn’t random at all.”

Medin’s math is based on the number of password combinations possible with a 10-character password. Assuming it used a randomly generated assortment of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters, the number of different combinations would be 9510—that is, the number of possible characters (95) raised to the power of 10, the number of characters used in the password. Even when hashed with the insecure NTLM function the old authentication uses, such a password would take more than five years for a brute-force attack to exhaust every possible combination. Exhausting every possible 25-character password would require more time than the universe has existed.

“The password was clearly not randomly generated. (Or if it was, was way too short… which would be really odd),” Medin added. Ascension “admins selected a password that was crackable and did not use the recommended Managed Service Account as prescribed by Microsoft and others.”

It’s not clear precisely how long the Ascension attackers spent trying to crack the stolen hash before succeeding. Wyden said only that the laptop compromise occurred in February 2024. Ascension, meanwhile, has said that it first noticed signs of the network compromise on May 8. That means the offline portion of the attack could have taken as long as three months, which would indicate the password was at least moderately strong. The crack may have required less time, since ransomware attackers often spend weeks or months gaining the access they need to encrypt systems.

Richard Gold, an independent researcher with expertise in Active Directory security, agreed the strength of the password is suspect, but he went on to say that based on Wyden’s account of the breach, other security lapses are also likely.

“All the boring, unsexy but effective security stuff was missing—network segmentation, principle of least privilege, need to know and even the kind of asset tiering recommended by Microsoft,” he wrote. “These foundational principles of security architecture were not being followed. Why?”

Chief among the lapses, Gold said, was the failure to properly allocate privileges, which likely was the biggest contributor to the breach.

“It’s obviously not great that obsolete ciphers are still in use and they do help with this attack, but excessive privileges are much more dangerous,” he wrote. “It’s basically an accident waiting to happen. Compromise of one user’s machine should not lead directly to domain compromise.”

Ascension didn’t respond to emails asking about the compromised password and other of its security practices.

Kerberos and Active Directory 101

Kerberos was developed in the 1980s as a way for two or more devices—typically a client and a server—inside a non-secure network to securely prove their identity to each other. The protocol was designed to avoid long-term trust between various devices by relying on temporary, limited-time credentials known as tickets. This design protects against replay attacks that copy a valid authentication request and reuse it to gain unauthorized access. The Kerberos protocol is cipher- and algorithm-agnostic, allowing developers to choose the ones most suitable for the implementation they’re building.

Microsoft’s first Kerberos implementation protects a password from cracking attacks by representing it as a hash generated with a single iteration of Microsoft’s NTLM cryptographic hash function, which itself is a modification of the super-fast, and now deprecated, MD4 hash function. Three decades ago, that design was adequate, and hardware couldn’t support slower hashes well anyway. With the advent of modern password-cracking techniques, all but the strongest Kerberos passwords can be cracked, often in a matter of seconds. The first Windows version of Kerberos also uses RC4, a now-deprecated symmetric encryption cipher with serious vulnerabilities that have been well documented over the past 15 years.

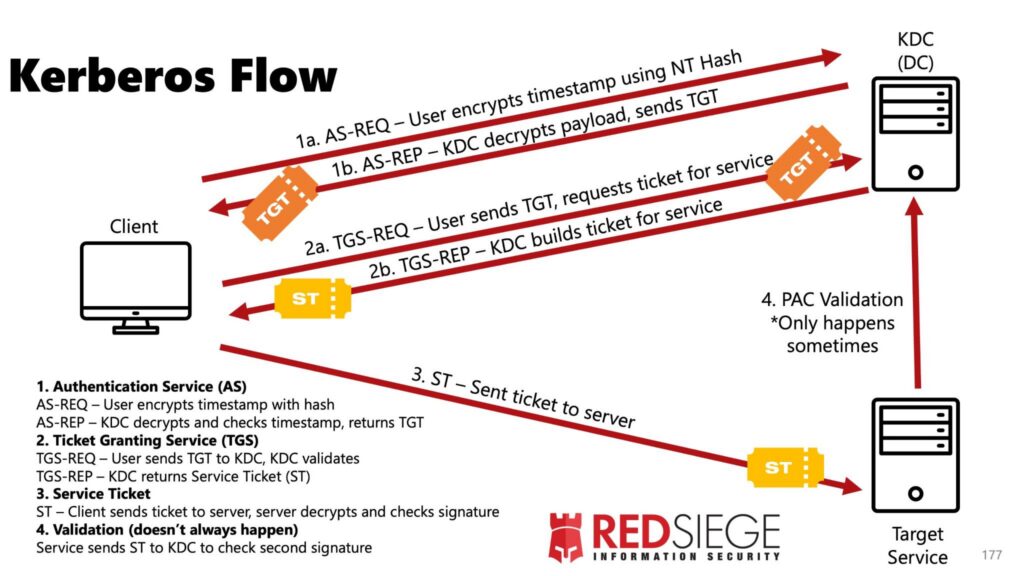

A very simplified description of the steps involved in Kerberos-based Active Directory authentication is:

1a. The client sends a request to the Windows Domain Controller (more specifically a Domain Controller component known as the KDC) for a TGT, short for “Ticket-Granting Ticket.” To prove that the request is coming from an account authorized to be on the network, the client encrypts the timestamp of the request using the hash of its network password. This step, and step 1b below, occur each time the client logs in to the Windows network.

1b. The Domain Controller checks the hash against a list of credentials authorized to make such a request (i.e., is authorized to join the network). If the Domain Controller approves, it sends the client a TGT that’s encrypted with the password hash of the KRBTGT, a special account only known to the Domain Controller. The TGT, which contains information about the user such as the username and group memberships, is stored in the computer memory of the client.

2a. When the client needs access to a service such as the Microsoft SQL server, it sends a request to the Domain Controller that’s appended to the encrypted TGT stored in memory.

2b. The Domain Controller verifies the TGT and builds a service ticket. The service ticket is encrypted using the password hash of SQL or another service and sent back to the account holder.

3a. The account holder presents the encrypted service ticket to the SQL server or the other service.

3b. The service decrypts the ticket and checks if the account is allowed access on that service and if so, with what level of privileges.

With that, the service grants the account access. The following image illustrates the process, although the numbers in it don’t directly correspond to the numbers in the above summary.

Credit: Tim Medin/RedSiege

Getting roasted

In 2014, Medin appeared at the DerbyCon Security Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, and presented an attack he had dubbed Kerberoasting. It exploited the ability for any valid user account—including a compromised one—to request a service ticket (step 2a above) and receive an encrypted service ticket (step 2b).

Once a compromised account received the ticket, the attacker downloaded the ticket and carried out an offline cracking attack, which typically uses large clusters of GPUs or ASIC chips that can generate large numbers of password guesses. Because Windows by default hashed passwords with a single iteration of the fast NTLM function using RC4, these attacks could generate billions of guesses per second. Once the attacker guessed the right combination, they could upload the compromised password to the compromised account and use it to gain unauthorized access to the service, which otherwise would be off limits.

Even before Kerberoasting debuted, Microsoft in 2008 introduced a newer, more secure authentication method for Active Directory. The method also implemented Kerberos but relied on the time-tested AES256 encryption algorithm and iterated the resulting hash 4,096 times by default. That meant the newer method made offline cracking attacks much less feasible, since they could make only millions of guesses per second. Out of concern for breaking older systems that didn’t support the newer method, though, Microsoft didn’t make it the default until 2020.

Even in 2025, however, Active Directory continues to support the old RC4/NTLM method, although admins can configure Windows to block its usage. By default, though, when the Active Directory server receives a request using the weaker method, it will respond with a ticket that also uses it. The choice is the result of a tradeoff Windows architects made—the continued support of legacy devices that remain widely used and can only use RC4/NTLM at the cost of leaving networks open to Kerberoasting.

Many organizations using Windows understand the trade-off, but many don’t. It wasn’t until last October—five months after the Ascension compromise—that Microsoft finally warned that the default fallback made users “more susceptible to [Kerberoasting] because it uses no salt or iterated hash when converting a password to an encryption key, allowing the cyberthreat actor to guess more passwords quickly.”

Microsoft went on to say that it would disable RC4 “by default” in non-specified future Windows updates. Last week, in response to Wyden’s letter, the company said for the first time that starting in the first quarter of next year, new installations of Active Directory using Windows Server 2025 will, by default, disable the weaker Kerberos implementation.

Medin questioned the efficacy of Microsoft’s plans.

“The problem is, very few organizations are setting up new installations,” he explained. “Most new companies just use the cloud, so that change is largely irrelevant.”

Ascension called to the carpet

Wyden has focused on Microsoft’s decision to continue supporting the default fallback to the weaker implementation; to delay and bury formal warnings that make customers susceptible to Kerberoasting; and to not mandate that passwords be at least 14 characters long, as Microsoft’s guidance recommends. To date, however, there has been almost no attention paid to Ascension’s failings that made the attack possible.

As a health provider, Ascension likely uses legacy medical equipment—an older X-ray or MRI machine, for instance—that can only connect to Windows networks with the older implementation. But even then, there are measures the organization could have taken to prevent the one-two pivot from the infected laptop to the Active Directory, both Gold and Medin said. The most likely contributor to the breach, both said, was the crackable password. They said it’s hard to conceive of a truly random password with 14 or more characters that could have suffered that fate.

“IMO, the bigger issue is the bad passwords behind Kerberos, not as much RC4,” Medin wrote in a direct message. “RC4 isn’t great, but with a good password you’re fine.” He continued:

Yes, RC4 should be turned off. However, Kerberoasting still works against AES encrypted tickets. It is just about 1,000 times slower. If you compare that to the additional characters, even making the password two characters longer increases the computational power 5x more than AES alone. If the password is really bad, and I’ve seen plenty of those, the additional 1,000x from AES doesn’t make a difference.

Medin also said that Ascension could have protected the breached service with Managed Service Account, a Microsoft service for managing passwords.

“MSA passwords are randomly generated and automatically rotated,” he explained. “It 100% kills Kerberoasting.”

Gold said Ascension likely could have blocked the weaker Kerberos implementation in its main network and supported it only in a segmented part that tightly restricted the accounts that could use it. Gold and Medin said Wyden’s account of the breach shows Ascension failed to implement this and other standard defensive measures, including network intrusion detection.

Specifically, the ability of the attackers to remain undetected between February—when the contractor’s laptop was infected—and May—when Ascension first detected the breach—invites suspicions that the company didn’t follow basic security practices in its network. Those lapses likely include inadequate firewalling of client devices and insufficient detection of compromised devices and ongoing Kerberoasting and similar well-understood techniques for moving laterally throughout the health provider network, the researchers said.

The catastrophe that didn’t have to happen

The results of the Ascension breach were catastrophic. With medical personnel locked out of electronic health records and systems for coordinating basic patient care such as medications, surgical procedures, and tests, hospital employees reported lapses that threatened patients’ lives. The ransomware also stole the medical records and other personal information of 5.6 million patients. Disruptions throughout the Ascension health network continued for weeks.

Amid Ascension’s decision not to discuss the attack, there aren’t enough details to provide a complete autopsy of Ascension’s missteps and the measures the company could have taken to prevent the network breach. In general, though, the one-two pivot indicates a failure to follow various well-established security approaches. One of them is known as security in depth. The security principle is similar to the reason submarines have layered measures to protect against hull breaches and fighting onboard fires. In the event one fails, another one will still contain the danger.

The other neglected approach—known as zero trust—is, as WIRED explains, a “holistic approach to minimizing damage” even when hack attempts do succeed. Zero-trust designs are the direct inverse of the traditional, perimeter-enforced hard on the outside, soft on the inside approach to network security. Zero trust assumes the network will be breached and builds the resiliency for it to withstand or contain the compromise anyway.

The ability of a single compromised Ascension-connected computer to bring down the health giant’s entire network in such a devastating way is the strongest indication yet that the company failed its patients spectacularly. Ultimately, the network architects are responsible, but as Wyden has argued, Microsoft deserves blame, too, for failing to make the risks and precautionary measures for Kerberoasting more explicit.

As security expert HD Moore observed in an interview, if the Kerberoasting attack wasn’t available to the ransomware hackers, “it seems likely that there were dozens of other options for an attacker (standard bloodhound-style lateral movement, digging through logon scripts and network shares, etc).” The point being: Just because a target shuts down one viable attack path is no guarantee that others remain.

All of that is undeniable. It’s also indisputable that in 2025, there’s no excuse for an organization as big and sensitive as Ascension suffering a Kerberoasting attack, and that both Ascension and Microsoft share blame for the breach.

“When I came up with Kerberoasting in 2014, I never thought it would live for more than a year or two,” Medin wrote in a post published the same day as the Wyden letter. “I (erroneously) thought that people would clean up the poor, dated credentials and move to more secure encryption. Here we are 11 years later, and unfortunately it still works more often than it should.”

Dan Goodin is Senior Security Editor at Ars Technica, where he oversees coverage of malware, computer espionage, botnets, hardware hacking, encryption, and passwords. In his spare time, he enjoys gardening, cooking, and following the independent music scene. Dan is based in San Francisco. Follow him at here on Mastodon and here on Bluesky. Contact him on Signal at DanArs.82.