generative AI could never

The world’s oldest art has an unintentional story to tell about human exploration.

These 17,000-year-old hand stencils from Liang Jarie Maros, in another area of Sulawesi, bear a striking resemblance to the much older ones in Liang Metanduno. Credit: OKtaviana et al. 2026

The world’s oldest surviving rock art is a faded outline of a hand on an Indonesian cave wall, left 67,800 years ago.

On a tiny island just off the coast of Sulawesi (a much larger island in Indonesia), a cave wall bears the stenciled outline of a person’s hand—and it’s at least 67,800 years old, according to a recent study. The hand stencil is now the world’s oldest work of art (at least until archaeologists find something even older), as well as the oldest evidence of our species on any of the islands that stretch between continental Asia and Australia.

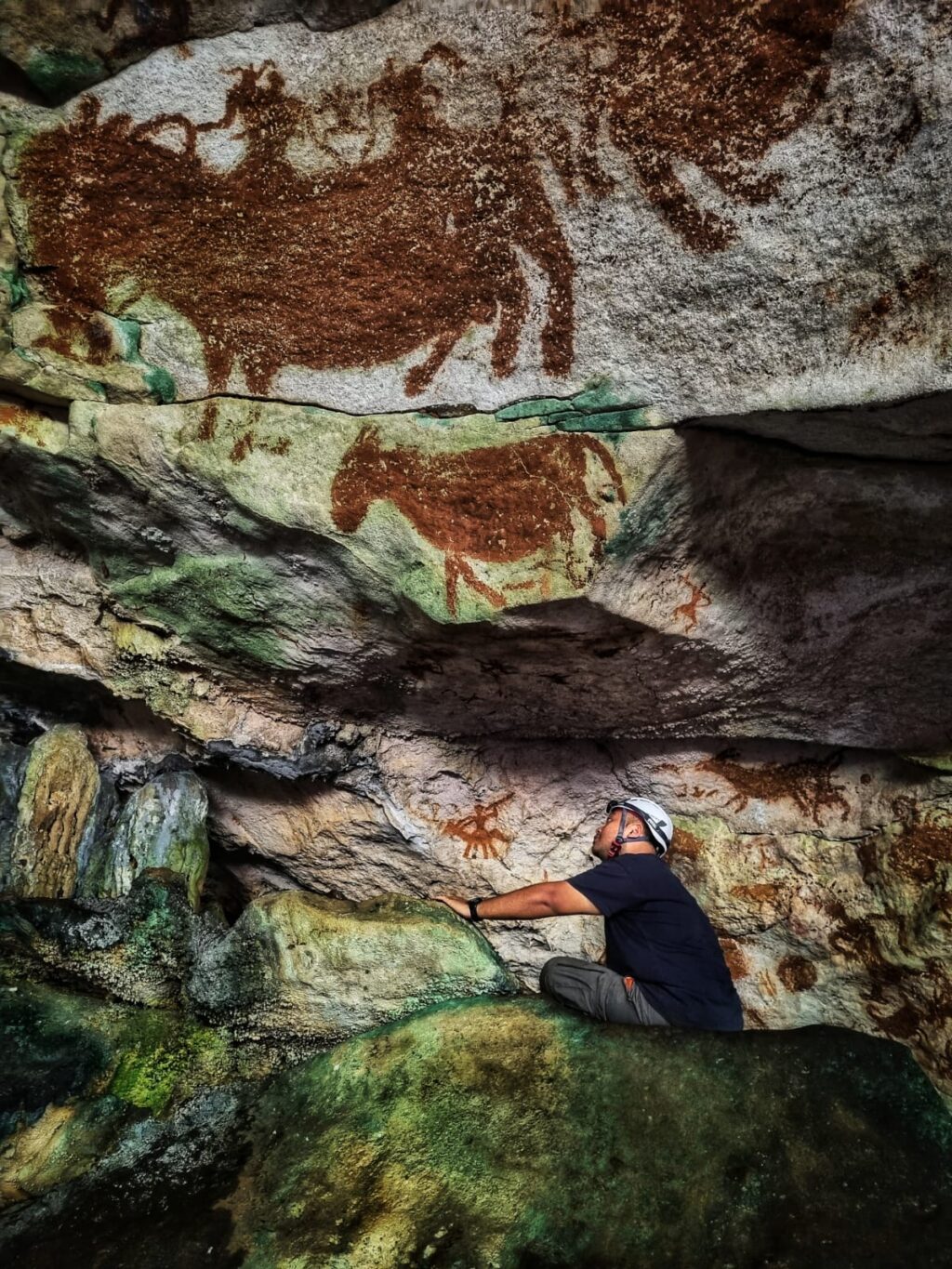

Adhi Oktaviana examines a slightly more recent hand stencil on the wall of Liang Metanduno. Credit: Oktaviana et al. 2026

Hands reaching out from the past

Archaeologist Adhi Agus Oktaviana, of Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency, and his colleagues have spent the last six years surveying 44 rock art sites, mostly caves, on Sulawesi’s southeastern peninsula and the handful of tiny “satellite islands” off its coast. They found 14 previously undocumented sites and used rock formations to date 11 individual pieces of rock art in eight caves—including the oldest human artwork discovered so far.

About 67,800 years ago, someone stood in the darkness of Liang Metanduno and placed their hand flat against the limestone wall. They, or maybe a friend, then blew a mixture of pigment and water onto the wall, covering and surrounding their hand. When they pulled their hand carefully away from the rock, careful not to disturb the still-wet paint, they left behind a crisp outline of their palm and fingers, haloed by a cloud of deep red.

The result is basically the negative of a handprint, and it’s a visceral, tangible link to the past. Someone once laid their hand on the cave wall right here, and you can still see its outline like a lingering ghost, reaching out from the other side of the rock. If you weren’t worried about damaging the already faded and fragile image, you could lay your hand in the same spot and meet them halfway.

Today, the stencil is so faded that you can barely see it, but if you look closely, it’s there: a faint halo of reddish-orange pigment, outlining the top part of a palm and the base of the fingers. A thin, nearly transparent layer of calcite covers the faded shape, left behind by millennia of water dripping down the cave wall. The ratio of uranium and thorium in a sheet of calcite suggests that it formed at least 71,000 years ago—so the outline of the hand beneath it must have been left behind sometime before that, probably around 67,800 years ago.

The hand stencil is faded and overlain by more recent (but still ancient) artwork; it’s circled in black to help you find it in this photo. Credit: Oktaviana et al. 2026

That makes Liang Metanduno the home of the oldest known artwork in the world, beating the previous contender (a Neanderthal hand stencil in Spain) by about 1,100 years.

“These findings support the growing view that Sulawesi was host to a vibrant and longstanding artistic culture during the late Pleistocene epoch,” wrote Oktaviana and his colleagues in their recent paper.

The karst caves of Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula, Maros-Pangkep, are a treasure trove of deeply ancient artwork: hand stencils, as well as drawings of wild animals, people, and strange figures that seem to blend the two. A cave wall at Liang Bulu’Sipong 4 features a 4.5-meter-long mural of humanlike figures facing off against wild pigs and dwarf buffalo, and a 2024 study pushed the mural’s age back to 51,200 years ago, making it the second-oldest artwork that we know of (after the Liang Metanduno hand stencil in the recent study).

Archaeologists have only begun to rediscover the rock art of Maros-Pangkep in the last decade or so, and other areas of the island, like Southeast Sulawesi and its tiny satellite islands, have received even less attention—so we don’t know what’s still there waiting for humanity to find again after dozens of millennia. We also don’t know what the ancient artist was trying to convey with the outline of their hand on the cave wall, but part of the message rings loud and clear across tens of millennia: At least 67,800 years ago, someone was here.

Really, really ancient mariners

The hand stencil on the wall of Liang Metanduno is, so far, the oldest evidence of our presence in Wallacea, the group of islands stretched between the continental shelves of Asia and Australia. Populating these islands is “widely considered to have involved the first planned, long-distance sea crossing undertaken by our species,” wrote Oktaviana and his colleagues.

Back when the long-lost artist laid their hand on the wall, sea levels were about 100 meters lower than they are today. Mainland Asia, Sumatra, and Borneo would have been high points in a single landmass, joined by wide swaths of lowlands that today lie beneath shallow ocean. The eastern shore of Borneo would have been a jumping-off point, beyond which lay several dozen kilometers of water and (out of view over the horizon) Sulawesi.

The first few people may have washed ashore on Sulawesi on some misadventure: lost fishermen or tsunami survivors, maybe. But at some point, people must have started making the crossing on purpose, which implies that they knew how to build rafts or boats, how to steer them, and that land awaited them on the other side.

Liang Metanduno pushes back the timing of that crossing by nearly 10,000 years. It also lends strong support to arguments that people arrived in Australia earlier than archaeologists had previously suspected. Archaeological evidence from a rock shelter called Madjedbebe, in northern Australia, suggests that people were living there by 65,000 years ago. But that evidence is still debated (such is the nature of archaeology), and some archaeologists argue that humans didn’t reach the continent until around 50,000 years ago.

“With the discovery of rock art dating to at least 67,800 years ago in Sulawesi, a large island on the most plausible colonization route to Australia, it is increasingly likely that the controversial date of 65,000 years for the initial peopling of Australia is correct,” Griffith University archaeologists Adam Brumm, a coauthor of the recent study, told Ars.

Archaeologists Shinatria Adhityatama studies a panel of ancient paintings in Liang Metanduno. Credit: Oktaviana et al. 2026

Archaeologists are still trying to work out exactly when, where, and how the first members of our species made the leap from the continent of Asia to the islands of Wallacea and, eventually, via several more open-water crossings, to Australia. Our picture of the process is pieced together from archaeological finds and models of ancient geography and sea levels.

“There’s been all sorts of work done on this (not by me), but often researchers consider the degree of intervisibility between islands, as well as other things like prevailing ocean currents and wind directions, changes in sea levels and how this affects the land area of islands and shorelines and so on,” Brumm said.

Most of those models suggest that people crossed the Makassar Strait from Borneo to Sulawesi, then island-hopped through what’s now Indonesia until they reached the western edge of New Guinea. At the time, lower sea levels would have left New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand as one big land mass, so getting from New Guinea to what’s now Australia would actually have been the easy part.

A time capsule on the walls

There’s a sense of deep, deep time in Liang Metanduno. The cave wall is a palimpsest on which the ancient hand stencil is nearly covered by a brown-hued drawing of a chicken, which (based on its subject matter) must have been added sometime after 5,000 years ago, when a new wave of settlers brought domesticated chickens to the island. It seems almost newfangled against the ghostly faint outline of the Paleolithic hand.

A few centimeters away is another hand stencil, done in darker pigment and dating to around 21,500 years ago; it overlays a lighter stencil dating to around 60,900 years ago. Over tens of thousands of years, generations of people returned here with the same impulse. We have no way of knowing whether visitors 21,500 years ago, or 5,000 years ago might have seen a more vibrantly decorated cave wall than what’s preserved today—but we know that they decided to leave their mark on it.

And the people who visited the cave 21,500 years ago shared a sense of style with the artists who left their hands outlined on the wall nearly 40,000 years before them: both handprints have slightly pointed fingers, as if the artist either turned their fingertip or just touched-up the outline with some paint after making the stencil. It’s very similar to other hand stencils, dated to around 17,000 years ago, from elsewhere on Sulawesi, and it’s a style that seems unique to the island.

“We may conclude that this regionally unique variant of stencil art is much older than previously thought,” wrote Oktaviana and his colleagues.

These 17,000-year-old hand stencils from Liang Jarie Maros, in another area of Sulawesi, bear a striking resemblance to the much older ones in Liang Metanduno. Credit: OKtaviana et al. 2026

And Homo sapiens wasn’t the first hominin species to venture as far as Indonesia; at least 200,000 years earlier, Homo erectus made a similar journey, leaving behind fossils and stone tools to mark that they, too, were once here. On some of the smaller islands, isolated populations of Homo erectus started to evolve along their own paths, eventually leading to diminutive species like Homo floresiensis (the O.G. hobbits) on Flores and Homo luzonensis on Luzon. Homo floresiensis co-discoverer Richard Roberts has suggested that other isolated hominin species may have existed on other scattered islands.

Anthropologists haven’t found any fossil evidence of these species after 50,000 years ago, but if our species was in Indonesia by nearly 68,000 years ago, we would have been in time to meet our hominin cousins.

Nature, 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09968-y (About DOIs).