“The combination of shaping, wear, and resharpening indicates they were used to draw or mark on soft surfaces,” D’Errico told Ars in an email. “Although the material is too fragile to reveal the specific material on which they were used, such as hide, human skin, or stone, an experimental approach may, in the future, allow us at least to rule out their use on some materials.”

A 73,000-year-old drawing from Blombo Cave in South Africa looks like it was made with tools much like the ocher crayons from Crimea, which means that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens both invented crayons in their own little corners of the world at around the same time.

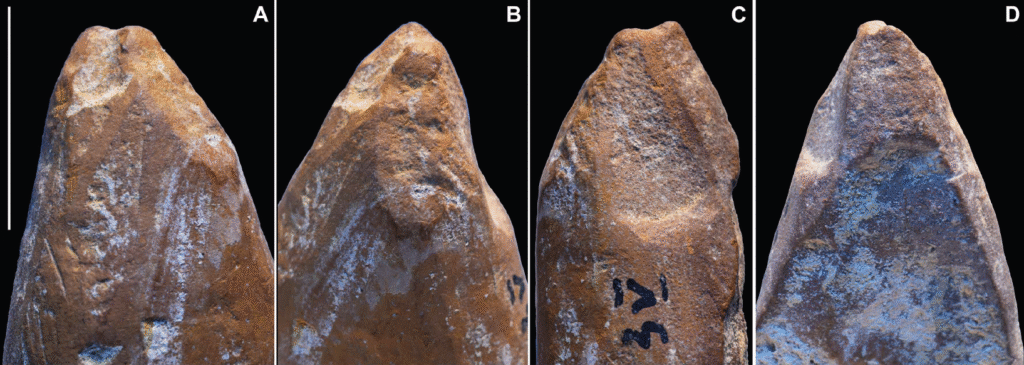

The surface of this flat piece of orange ocher was carved over 47,000 years ago, then worn smooth, perhaps by carrying in a bag. Credit: D’Errico et al. 2025

Sometimes you’re the crayon, sometimes you’re the canvas

A third item from Zaskalnaya V is a flat piece of orange ocher. One side is covered with a thin layer of hard, dark rock. But more than 47,000 years ago, someone carefully cut several deep lines, regularly spaced and almost parallel, into its surface. The area of stone between the lines has been worn and polished smooth, suggesting that someone carried it and handled it for years.

“The polish smoothing the engraved lines suggest that the piece was curated, perhaps transported in a bag,” D’Errico told Ars. Whoever carved the lines into the piece of ocher also appears to have been right-handed, based on the angle of the incisions’ walls.

The finds join a host of other evidence of Neanderthal artwork and jewelry, from 57,000-year-old finger marks on a cave wall in France to 114,000-year-old ocher-painted shells in Spain.

“Traditionally viewed as lacking the cognitive flexibility and symbolic capacity of humans, the Neanderthals of Crimea demonstrate the opposite: They engaged in cultural practices that were not merely adaptive but deeply meaningful,” wrote D’Errico and his colleagues. “Their sophisticated use of ocher is one facet of their complex cultural life.”

The tip of this red ocher crayon was broken off. Credit: D’Errico et al. 2025

Coloring in some details of Neanderthal culture

It’s hard to say whether the rest of the ocher from the Zaskalnaya sites and other nearby rock shelters meant anything to the Neanderthals beyond the purely pragmatic. However, it’s unlikely that humans (of any stripe) could spend 70,000 years working with vividly colored pigment without developing a sense of aesthetics, assigning some meaning to the colors, or maybe doing both.