STARBASE, Texas—I first visited SpaceX’s launch site in South Texas a decade ago. Driving down the pocked and barren two-lane road to its sandy terminus, I found only rolling dunes, a large mound of dirt, and a few satellite dishes that talked to Dragon spacecraft as they flew overhead.

A few years later, in mid-2019, the company had moved some of that dirt and built a small launch pad. A handful of SpaceX engineers working there at the time shared some office space nearby in a tech hub building, “Stargate.” The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley proudly opened this state-of-the-art technology center just weeks earlier. That summer, from Stargate’s second floor, engineers looked on as the Starhopper prototype made its first two flights a couple of miles away.

Over the ensuing years, as the company began assembling its Starship rockets on site, SpaceX first erected small tents, then much larger tents, and then towering high bays in which the vehicles were stacked. Starbase grew and evolved to meet the company’s needs.

All of this was merely a prelude to the end game: Starfactory. SpaceX opened this truly massive facility earlier this year. The sleek rocket factory is emblematic of the new Starbase: modern, gargantuan, spaceship-like.

To the consternation of some local residents and environmentalists, the rapid growth of Starbase has wiped out the small and eclectic community that existed here. And that brand new Stargate building that public officials were so excited about only a few years ago? SpaceX first took it over entirely and then demolished it. The tents are gone, too. For better or worse, in the name of progress, the SpaceX steamroller has rolled onward, paving all before it.

Starbase is even its own Texas city now. And if this were a medieval town, Starfactory would be the impenetrable fortress at its heart. In late May, I had a chance to go inside. The interior was super impressive, of course. Yet it could not quell some of the concerns I have about the future of SpaceX’s grand plans to send a fleet of Starships into the Solar System.

Inside the fortress

The main entrance to the factory lies at its northeast corner. From there, one walks into a sleek lobby that serves as a gateway into the main, cavernous section of the building. At this corner, there are three stories above the ground floor. Each of these three higher levels contains various offices, conference rooms and, on the upper floor, a launch control center.

Large windows from here offer a breathtaking view of the Starship launch site two miles up the road. A third-floor executive conference room has carpet of a striking rusty, reddish hue—mimicking the surface of Mars, naturally. A long, black table dominates the room, with 10 seats along each side, and one at the head.

An aerial overview of the Starship production site in South Texas earlier this year. The sprawling Starfactory is in the center. Credit: SpaceX

But the real attraction of these offices is the view to the other end. Each of the upper three floors has a balcony overlooking the factory floor. From there, it’s as if one stands at the edge of an ocean liner, gazing out to sea. In this case, the far wall is discernible, if only barely. Below, the factory floor is crammed with all manner of Starship parts: nose cones, grid fins, hot staging rings, and so much more. The factory emitted a steady din and hum as work proceeded on vehicles below.

The ultimate goal of this factory is to build one Starship rocket a day. This sounds utterly mad. For the entire Apollo program in the 1960s and 1970s, NASA built 15 Saturn V rockets. Over the course of more than three decades, NASA built and flew only five different iconic Space Shuttles. SpaceX aims to build 365 vehicles, which are larger, per year.

Wandering around the Starfactory, however, this ambition no longer seems undoable. The factory measures about 1 million square feet. This is two times as large as SpaceX’s main Falcon 9 factory in Hawthorne, California. It feels like the company could build a lot of Starships here if needed.

During one of my visits to South Texas, in early 2020 just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, SpaceX was building its first Starship rockets in football field-sized tents. At the time, SpaceX founder Elon Musk opined in an interview that building the factory might well be more difficult than building the rocket.

Here’s a view of SpaceX’s Starship production facilities, from the east side, in late February 2020. Credit: Eric Berger

“If you want to actually make something at reasonable volume, you have to build the machine that makes the machine, which mathematically is going to be vastly more complicated than the machine itself,” he said. “The thing that makes the machine is not going to be simpler than the machine. It’s going to be much more complicated, by a lot.”

Five years later, standing inside Starfactory, it seems clear that SpaceX has built the machine to build the machine—or at least it’s getting close.

But what happens if that machine is not ready for prime time?

A pretty bad year for Starship

SpaceX has not had a good run of things with the ambitious Starship vehicle this year. Three times, in January, March, and May, the vehicle took flight. And three times, the upper stage experienced significant problems during ascent, and the vehicle was lost on the ride up to space, or just after. These were the seventh, eighth, and ninth test flights of Starship, following three consecutive flights in 2024 during which the Starship upper stage made more or less nominal flights and controlled splashdowns in the Indian Ocean.

It’s difficult to view the consecutive failures this year—not to mention the explosion of another Starship vehicle during testing in June—as anything but a major setback for the program.

There can be no question that the Starship rocket, with its unprecedentedly large first stage and potentially reusable upper stage, is the most advanced and ambitious rocket humans have ever conceived, built, and flown. The failures this year, however, have led some space industry insiders to ask whether Starship is too ambitious.

My sources at SpaceX don’t believe so. They are frustrated by the run of problems this year, but they believe the fundamental design of Starship is sound and that they have a clear path to resolving the issues. The massive first stage has already been flown, landed, and re-flown. This is a huge step forward. But the sources also believe the upper stage issues can be resolved, especially with a new “Version 3” of Starship due to make its debut late this year or early in 2026.

The acid test will only come with upcoming flights. The vehicle’s tenth test flight is scheduled to take place no earlier than Sunday, August 24. It’s possible that SpaceX will fly one more “Version 2” Starship later this year before moving to the upgraded vehicle, with more powerful Raptor engines and lots of other changes to (hopefully) improve reliability.

SpaceX could certainly use a win. The Starship failures occur at a time when Musk has become embroiled in political controversy while feuding with the president of the United States. His actions have led some in government and private industry to question whether they should be doing business with SpaceX going forward.

It’s often said in sports that winning solves a lot of problems. For SpaceX, success with Starship would solve a lot of problems.

Next steps for Starship

The failures are frustrating and publicly embarrassing. But more importantly, they are a bottleneck for a lot of critical work SpaceX needs to do for Starship to reach its considerable potential. All of the technical progress the Starship program needs to make to deploy thousands of Starlink satellites, land NASA astronauts on the Moon, and send humans to Mars remains largely on hold.

Two of the most important objectives for the next flight require the Starship vehicle to fly a nominal mission. For several flights now, SpaceX engineers have dutifully prepared Starlink satellite simulators to test a Pez-like dispenser in space. And each Starship vehicle has carried about two dozen different tile experiments as the company attempts to build a rapidly reusable heat shield to protect Starship during atmospheric reentry.

The engineers are still waiting for the results of their experiments.

In the near term, SpaceX is hyper-focused on getting Starship working and starting the deployment of large Starlink satellites that will have the potential to unlock significant amounts of revenue. But this is just the beginning of the work that needs to happen for SpaceX to turn Starship into a deep-space vehicle capable of traveling to the Moon and Mars.

These steps include:

- Reuse: Developing a rapidly reusable heat shield and landing and re-flying Starship upper stages

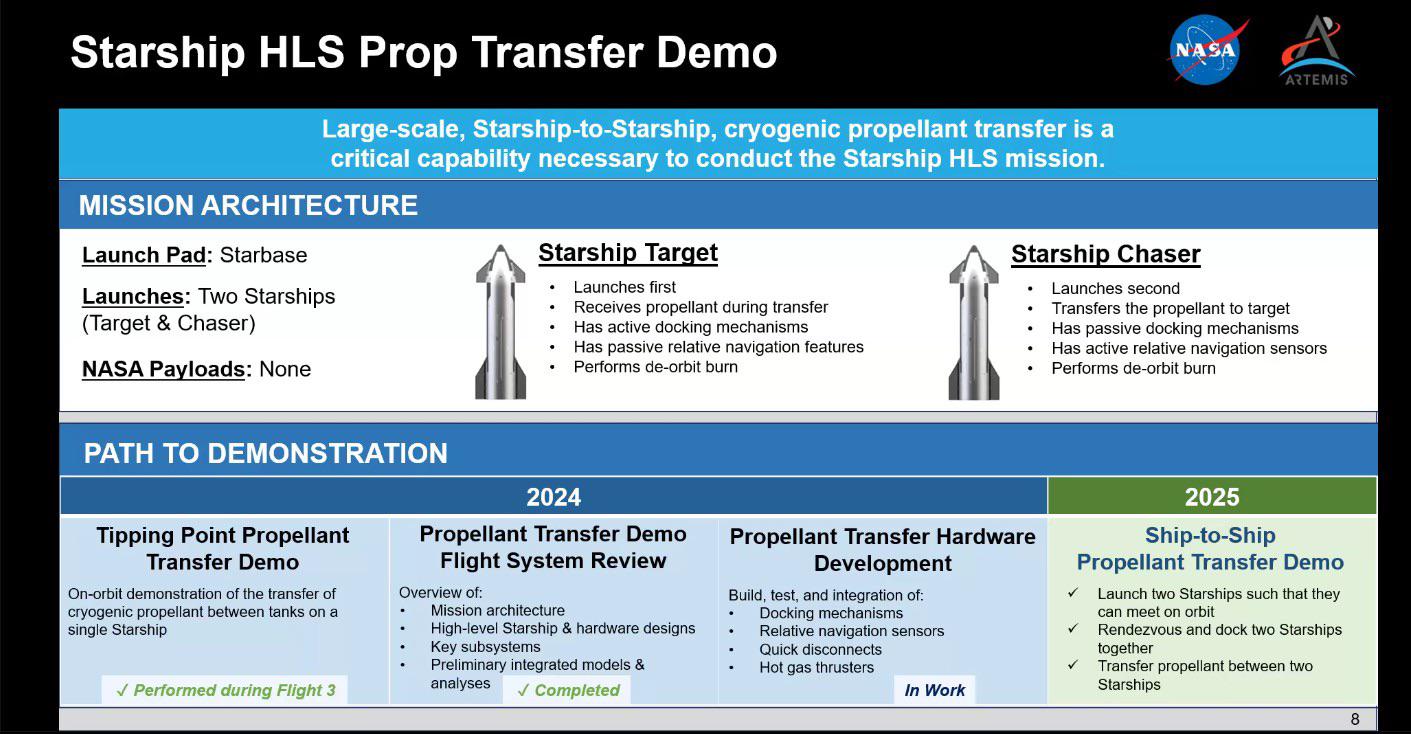

- Prop transfer: Conducting a refueling test in low-Earth orbit to demonstrate the transfer of large amounts of propellant between Starships

- Depots: Developing and testing cryogenic propellant depots to understand heating losses over time

- Lunar landing: Landing a Starship successfully on the Moon, which is challenging due to the height of the vehicle and uneven terrain

- Lunar launch: Demonstrating the capability of Starship, using liquid propellant, to launch safely from the lunar surface without infrastructure there

- Mars transit: Demonstrating the operation of Starship over months and the capability to perform a powered landing on Mars.

Each of these steps is massively challenging and at least partly a novel exercise in aerospace. There will be a lot of learning, and almost certainly some failures, as SpaceX works through these technical milestones.

Some details about the Starship propellant transfer test, a key milestone that NASA and SpaceX had hoped to complete this year but now may tackle in 2026. Credit: NASA

SpaceX prefers a test, fly, and fix approach to developing hardware. This iterative approach has served the company well, allowing it to develop rockets and spacecraft faster and for less money than its competitors. But you cannot fly and fix hardware for the milestones above without getting the upper stage of Starship flying nominally.

That’s one reason why the Starship program has been so disappointing this year.

Then there are the politics

As SpaceX has struggled with Starship in 2025, its founder, Musk, has also had a turbulent run, from the presidential campaign trail to the top of political power in the world, the White House, and back out of President Trump’s inner circle. Along the way, he has made political enemies, and his public favorability ratings have fallen.

Amid the fallout between Trump and Musk this spring and summer, the president ordered a review of SpaceX’s contracts. Nothing happened because government officials found that most of the services SpaceX offers to NASA, the US Department of Defense, and other federal agencies are vital.

However, multiple sources have told Ars that federal officials are looking for alternatives to SpaceX and have indicated they will seek to buy launches, satellite Internet, and other services from emerging competitors if available.

Starship’s troubles also come at a critical time in space policy. As part of its budget request for fiscal year 2026, the White House sought to terminate the production of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and spacecraft after the Artemis III mission. The White House has also expressed an interest in sending humans to Mars, viewing the Moon as a stepping stone to the red planet.

Although there are several options in play, the most viable hardware for both a lunar and Mars human exploration program is Starship. If it works. If it continues to have teething pains, though, that makes it easier for Congress to continue funding NASA’s expensive rocket and spacecraft, as it would prefer to do.

What about Artemis and the Moon?

Starship’s “lost year” also has serious implications for NASA’s Artemis Moon Program. As Ars reported this week, China is now likely to land on the Moon before NASA can return. Yes, the space agency has a nominal landing date in 2027 for the Artemis III mission, but no credible space industry officials believe that date is real. (It has already slipped multiple times from 2024). Theoretically, a landing in 2028 remains feasible, but a more rational over/under date for NASA is probably somewhere in the vicinity of 2030.

SpaceX is building the lunar lander for the Artemis III mission, a modified version of Starship. There is so much we don’t really know yet about this vehicle. For example, how many refuelings will it take to load a Starship with sufficient propellant to land on the Moon and take off? What will the vehicle’s controls look like, and will the landings be automated?

And here’s another one: How many people at SpaceX are actually working on the lunar version of Starship?

Publicly, Musk has said he doesn’t worry too much about China beating the United States back to the Moon. “I think the United States should be aiming for Mars, because we’ve already actually been to the Moon several times,” Musk said in an interview in late May. “Yeah, if China sort of equals that, I’m like, OK, sure, but that’s something that America did 56 years ago.”

Privately, Musk is highly critical of Artemis, saying NASA should focus on Mars. Certainly, that’s the long arc of history toward which SpaceX’s efforts are being bent. Although both the Moon and Mars versions of Starship require the vehicle to reach orbit and successfully refuel, there is a huge divergence in the technology and work required after that point.

It’s not at all clear that the Trump administration is seriously seeking to address this issue by providing SpaceX with carrots and sticks to move the lunar lander program forward. If Artemis is not a priority for Musk, how can it be for SpaceX?

This all creates a tremendous amount of uncertainty ahead of Sunday’s Starship launch. As Musk likes to say, “Excitement is guaranteed.”

Success would be better.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.