Perfumer by day, mixologist by night, Kevin Peterson specializes in crafting scent-paired cocktails.

Kevin Peterson is a “nose” for his own perfume company, Sfumato Fragrances, by day. By night, Sfumato’s retail store in Detroit transforms into Peterson’s craft cocktail bar, Castalia, where he is chief mixologist and designs drinks that pair with carefully selected aromas. He’s also the author of Cocktail Theory: A Sensory Approach to Transcendent Drinks, which grew out of his many (many!) mixology experiments and popular YouTube series, Objective Proof: The Science of Cocktails.

It’s fair to say that Peterson has had an unusual career trajectory. He worked as a line cook and an auto mechanic, and he worked on the production line of a butter factory, among other gigs, before attending culinary school in hopes of becoming a chef. However, he soon realized it wasn’t really what he wanted out of life and went to college, earning an undergraduate degree in physics from Carleton College and a PhD in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan.

After 10 years as an engineer, he switched focus again and became more serious about his side hobby, perfumery. “Not being in kitchens anymore, I thought—this is a way to keep that little flavor part of my brain engaged,” Peterson told Ars. “I was doing problem sets all day. It was my escape to the sensory realm. ‘OK, my brain is melting—I need a completely different thing to do. Let me go smell smells, escape to my little scent desk.'” He and his wife, Jane Larson, founded Sfumato, which led to opening Castalia, and Peterson finally found his true calling.

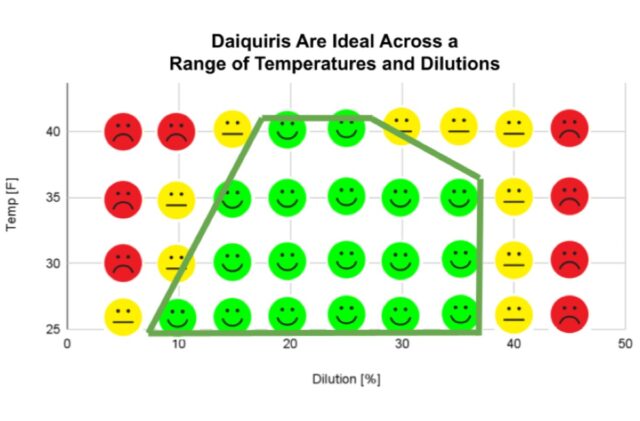

Peterson spent years conducting mixology experiments to gather empirical data about the interplay between scent and flavor, correct ratios of ingredients, temperature, and dilution for all the classic cocktails—seeking a “Platonic ideal,” for each, if you will. He supplemented this with customer feedback data from the drinks served at Castalia. All that culminated in Cocktail Theory, which delves into the chemistry of scent and taste, introducing readers to flavor profiles, textures, visual presentation, and other factors that contribute to one’s enjoyment (or lack thereof) of a cocktail. And yes, there are practical tips for building your own home bar, as well as recipes for many of Castalia’s signature drinks.

In essence, Peterson’s work adds scientific rigor to what is frequently called the “Mr. Potato Head” theory of cocktails, a phrase coined by the folks at Death & Company, who operate several craft cocktail bars in key cities. “Let’s say you’ve got some classic cocktail, a daiquiri, that has this many parts of rum, this many parts of lime, this many parts of sugar,” said Peterson, who admits to having a Mr. Potato Head doll sitting on Castalia’s back bar in honor of the sobriquet. “You can think about each ingredient in a more general way: instead of rum, this is the spirit; instead of lime, this is the citrus; sugars are sweetener. Now you can start to replace those things with other things in the same categories.”

We caught up with Peterson to learn more.

Ars Technica: How did you start thinking about the interplay between perfumery and cocktail design and the role that aroma plays in each?

Kevin Peterson: The first step was from food over to perfumery, where I think about building a flavor for a soup, for a sauce, for a curry, in a certain way. “Oh, there’s a gap here that needs to be filled in by some herbs, some spice.” It’s almost an intuitive kind of thing. When I was making scents, I had those same ideas: “OK, the shape of this isn’t quite right. I need this to roughen it up or to smooth out this edge.”

Then I did the same thing for cocktails and realized that those two worlds didn’t really talk to each other. You’ve got two groups of people that study all the sensory elements and how to create the most intriguing sensory impression, but they use different language; they use different toolkits. They’re going for almost the same thing, but there was very little overlap between the two. So I made that my niche: What can perfumery teach bartenders? What can the cocktail world teach perfumery?

Ars Technica: In perfumery you talk about a top, a middle, and a base note. There must be an equivalent in cocktail theory?

Kevin Peterson: In perfumery, that is mostly talking about the time element: top notes perceived first, then middle notes, then base notes as you wear it over the course of a few hours. In the cocktail realm, there is that time element as well. You get some impression when you bring the glass to your nose, something when you sip, something in the aftertaste. But there can also be a spatial element. Some things you feel right at the tip of your tongue, some things you feel in different parts of your face and head, whether that’s a literal impression or you just kind of feel it somewhere where there’s not a literal nerve ending. It’s about filling up that space, or not filling it up, depending on what impression you’re going for—building out the full sensory space.

Ars Technica: You also talk about motifs and supportive effects or ornamental flourishes: themes that you can build on in cocktails.

Kevin Peterson: Something I see in the cocktail world occasionally is that people just put a bunch of ingredients together and figure, “This tastes fine.” But what were you going for here? There are 17 things in here, and it just kind of tastes like you were finger painting: “Hey, I made brown.” Brown is nice. But the motifs that I think about—maybe there’s just one particular element that I want to highlight. Say I’ve got this really great jasmine essence. Everything else in the blend is just there to highlight the jasmine.

If you’re dealing with a really nice mezcal or bourbon or some unique herb or spice, that’s going to be the centerpiece. You’re not trying to get overpowered by some smoky scotch, by some other more intense ingredient. The motif could just be a harmonious combination of elements. I think the perfect old-fashioned is where everything is present and nothing’s dominating. It’s not like the bitters or the whiskey totally took over. There’s the bitters, there’s a little bit of sugar, there’s the spirit. Everything’s playing nicely.

Another motif, I call it a jazz note. A Sazerac is almost the same as an old-fashioned, but it’s got a little bit of absinthe in it. You get all the harmony of the old-fashioned, but then you’re like, “Wait, what’s this weird thing pulling me off to the side? Oh, this absinthe note is kind of separate from everything else that’s going on in the drink.” It’s almost like that tension in a musical composition: “Well, these notes sound nice, but then there’s one that’s just weird.” But that’s what makes it interesting, that weird note. For me, formalizing some of those motifs help me make it clearer. Even if I don’t tell that to the guest during the composition stage, I know this is the effect I’m going for. It helps me build more intentionally when I’ve got a motif in mind.

Ars Technica: I tend to think about cocktails more in terms of chemistry, but there are many elements to taste and perception and flavor. You talk about ingredient matching, molecular matching, and impression matching, i.e., how certain elements will overlap in the brain. What role do each of those play?

Kevin Peterson: A lot of those ideas relate to how we pair scents with cocktails. At my perfume company, we make eight fragrances as our main line. Each scent then gets a paired drink on the cocktail menu. For example, this scent has coriander, cardamom, and nutmeg. What does it mean that the drink is paired with that? Does it need to literally have coriander, cardamom, and nutmeg in it? Does it need to have every ingredient? If the scent has 15 things, do I need to hit every note?

Peterson made over 100 daiquiris to find the “Platonic ideal” of the classic cocktail Credit: Kevin Peterson

The literal matching is the most obvious. “This has cardamom, that has cardamom.” I can see how that pairs. The molecular matching is essentially just one more step removed: Rosemary has alpha-pinene in it, and juniper berries have alpha-pinene in them. So if the scent has rosemary and the cocktail has gin, they’re both sharing that same molecule, so it’s still exciting that same scent receptor. What I’m thinking about is kind of resonant effects. You’re approaching the same receptor or the same neural structure in two different ways, and you’re creating a bigger peak with that.

The most hand-wavy one to me is the impression matching. Rosemary smells cold, and Fernet-Branca tastes cold even when it’s room temperature. If the scent has rosemary, is Fernet now a good match for that? Some of the neuroscience stuff that I’ve read has indicated that these more abstract ideas are represented by the same sort of neural-firing patterns. Initially, I was hesitant; cold and cold, it doesn’t feel as fulfilling to me. But then I did some more reading and realized there’s some science behind it and have been more intrigued by that lately.

Ars Technica: You do come up with some surprising flavor combinations, like a drink that combined blueberry and horseradish, which frankly sounds horrifying.

Kevin Peterson: It was a hit on the menu. I would often give people a little taste of the blueberry and then a little taste of the horseradish tincture, and they’d say, “Yeah, I don’t like this.” And then I’d serve them the cocktail, and they’d be like, “Oh my gosh, it actually worked. I can’t believe it.” Part of the beauty is you take a bunch of things that are at least not good and maybe downright terrible on their own, and then you stir them all together and somehow it’s lovely. That’s basically alchemy right there.

Ars Technica: Harmony between scent and the cocktail is one thing, but you also talk about constructive interference to get a surprising, unexpected, and yet still pleasurable result.

Kevin Peterson: The opposite is destructive interference, where there’s just too much going on. When I’m coming up with a drink, sometimes that’ll happen, where I’m adding more, but the flavor impression is going down. It’s sort of a weird non-linearity of flavor, where sometimes two plus two equals four, sometimes it equals three, sometimes it equals 17. I now have intuition about that, having been in this world for a lot of years, but I still get surprised sometimes when I put a couple things together.

Often with my end-of-the-shift drink, I’ll think, “Oh, we got this new bottle in. I’m going to try that in a Negroni variation.” Then I lose track and finish mopping, and then I sip, and I’m like, “What? Oh my gosh, I did not see this coming at all.” That little spark, or whatever combo creates that, will then often be the first step on some new cocktail development journey.

Pairing scents with cocktails involves experimenting with many different ingredients Credit: EE Berger

Ars Technica: Smoked cocktails are a huge trend right now. What’s the best way to get a consistently good smoky element?

Kevin Peterson: Smoke is tricky to make repeatable. How many parts per million of smoke are you getting in the cocktail? You could standardize the amount of time that it’s in the box [filled with smoke]. Or you could always burn, say, exactly three grams of hickory or whatever. One thing that I found, because I was writing the book while still running the bar: People have a lot of expectations around how the drink is going to be served. Big ice cubes are not ideal for serving drinks, but people want a big ice cube in their old-fashioned. So we’re still using big ice cubes. There might be a Platonic ideal in terms of temperature, dilution, etc., but maybe it’s not the ideal in terms of visuals or tactile feel, and that is a part of the experience.

With the smoker, you open the doors, smoke billows out, your drink emerges from the smoke, and people say, “Wow, this is great.” So whether you get 100 PPM one time and 220 PPM the next, maybe that gets outweighed by the awesomeness of the presentation. If I’m trying to be very dialed in about it, I’ll either use a commercial smoky spirit—Laphroaig scotch, a smoky mezcal—where I decide that a quarter ounce is the amount of smokiness that I want in the drink. I can just pour the smoke instead of having to burn and time it.

Or I might even make my own smoke: light something on fire and then hold it under a bottle, tip it back up, put some vodka or something in there, shake it up. Now I’ve got smoke particles in my vodka. Maybe I can say, “OK, it’s always going to be one milliliter,” but then you miss out on the presentation—the showmanship, the human interaction, the garnish. I rarely garnish my own drinks, but I rarely send a drink out to a guest ungarnished, even if it’s just a simple orange peel.

Ars Technica: There’s always going to be an element of subjectivity, particularly when it comes to our sensory perceptions. Sometimes you run into a person who just can’t appreciate a certain note.

Kevin Peterson: That was something I grappled with. On the one hand, we’re all kind of living in our own flavor world. Some people are more sensitive to bitter. Different scent receptors are present in different people. It’s tempting to just say, “Well, everything’s so unique. Maybe we just can’t say anything about it at all.” But that’s not helpful either. Somehow, we keep having delicious food and drink and scents that come our way.

A sample page from Cocktail Theory discussing temperature and dilution. Credit: EE Berger

I’ve been taking a lot of survey data in my bar more recently, and definitely the individuality of preference has shown through in the surveys. But another thing that has shown through is that there are some universal trends. There are certain categories. There’s the spirit-forward, bittersweet drinkers, there’s the bubbly citrus folks, there’s the texture folks who like vodka soda. What is the taste? What is the aroma? It’s very minimal, but it’s a very intense texture. Having some awareness of that is critical when you’re making drinks.

One of the things I was going for in my book was to find, for example, the platonically ideal gin and tonic. What are the ratios? What is the temperature? How much dilution to how much spirit is the perfect amount? But if you don’t like gin and tonics, it doesn’t matter if it’s a platonically ideal gin and tonic. So that’s my next project. It’s not just getting the drink right. How do you match that to the right person? What questions do I have to ask you, or do I have to give you taste tests? How do I draw that information out of the customer to determine the perfect drink for them?

We offer a tasting menu, so our full menu is eight drinks, and you get a mini version of each drink. I started giving people surveys when they would do the tasting menu, asking, “Which drink do you think you like the most? Which drink do you think you like the least?” I would have them rate it. Less than half of people predicted their most liked and least liked, meaning if you were just going to order one drink off the menu, your odds are less than a coin flip that you would get the right drink.

Ars Technica: How does all this tie into your “cocktails as storytelling” philosophy?

Kevin Peterson: So much of flavor impression is non-verbal. Scent is very hard to describe. You can maybe describe taste, but we only have five-ish words, things like bitter, sour, salty, sweet. There’s not a whole lot to say about that: “Oh, it was perfectly balanced.” So at my bar, when we design menus, we’ll put the drinks together, but then we’ll always give the menu a theme. The last menu that we did was the scientist menu, where every drink was made in honor of some scientist who didn’t get the credit they were due in the time they were alive.

Having that narrative element, I think, helps people remember the drink better. It helps them in the moment to latch onto something that they can more firmly think about. There’s a conceptual element. If I’m just doing chores around the house, I drink a beer, it doesn’t need to have a conceptual element. If I’m going out and spending money and it’s my night and I want this to be a more elevated experience, having that conceptual tie-in is an important part of that.

My personal favorite drink, Corpse Reviver No. 2, has just a hint of absinthe. Credit: Sean Carroll

Ars Technica: Do you have any simple tips for people who are interested in taking their cocktail game to the next level?

Kevin Peterson: Old-fashioneds are the most fragile cocktail. You have to get all the ratios exactly right. Everything has to be perfect for an old-fashioned to work. Anecdotally, I’ve gotten a lot of old-fashioneds that were terrible out on the town. In contrast, the Negroni is the most robust drink. You can miss the ratios. It’s got a very wide temperature and dilution window where it’s still totally fine. I kind of thought of them in the same way prior to doing the test. Then I found that this band of acceptability is much bigger for the Negroni. So now I think of old-fashioneds as something that either I make myself or I order when I either trust the bartender or I’m testing someone who wants to come work for me.

My other general piece of advice: It can be a very daunting world to try to get into. You may say, “Oh, there’s all these classics that I’m going to have to memorize, and I’ve got to buy all these weird bottles.” My advice is to pick a drink you like and take baby steps away from that drink. Say you like Negronis. That’s three bottles: vermouth, Campari, and gin. Start with that. When you finish that bottle of gin, buy a different type of gin. When you finish the Campari, try a different bittersweet liqueur. See if that’s going to work. You don’t have to drop hundreds of dollars, thousands of dollars, to build out a back bar. You can do it with baby steps.

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.