Escaping from Monkey Island

Interview: Storied designer talks lost RPG, a 3D Monkey Island, “Eat the Rich” philosophy.

Gilbert, seen here circa 2017 promoting the release of point-and-click adventure throwback Thimbleweed Park. Credit: Getty Images

If you know the name Ron Gilbert, it’s probably for his decades of work on classic point-and-click adventure games like Maniac Mansion, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the Monkey Island series, and Thimbleweed Park. Given that pedigree, October’s release of the Gilbert-designed Death by Scrolling—a rogue-lite action-survival pseudo-shoot-em-up—might have come as a bit of a surprise.

In an interview from his New Zealand home, though, Gilbert noted that his catalog also includes some reflex-based games—Humungous Entertainment’s Backyard Sports titles and 2010’s Deathspank, for instance. And Gilbert said his return to action-oriented game design today stemmed from his love for modern classics like Binding of Isaac, Nuclear Throne, and Dead Cells.

“I mean, I’m certainly mostly known for adventure games, and I have done other stuff, [but] it probably is a little bit of a departure for me,” he told Ars. “While I do enjoy playing narrative games as well, it’s not the only thing I enjoy, and just the idea of making one of these kind of started out as a whim.”

Gilbert’s lost RPG

After spending years focused on adventure game development with 2017’s Thimbleweed Park and then 2022’s Return to Monkey Island, Gilbert said that he was “thinking about something new” for his next game project. But the first “new” idea he pursued wasn’t Death by Scrolling, but what he told Ars was “this vision for this kind of large, open world-type RPG” in the vein of The Legend of Zelda.

After hiring an artist and designer and spending roughly a year tinkering with that idea, though, Gilbert said he eventually realized his three-person team was never going to be able to realize his grand vision. “I just [didn’t] have the money or the time to build a big open-world game like that,” he said. “You know, it’s either a passion project you spent 10 years on, or you just need a bunch of money to be able to hire people and resources.”

And Gilbert said that securing that “bunch of money” to build out a top-down action-RPG in a reasonable time frame proved harder than he expected. After pitching the project around the industry, he found that “the deals that publishers were offering were just horrible,” a problem he blames in large part on the genre he was focusing on.

“Doing a pixelated old-school Zelda thing isn’t the big, hot item, so publishers look at us, and they didn’t look at it as ‘we’re gonna make $100 million and it’s worth investing in,’” he said. “The amount of money they’re willing to put up and the deals they were offering just made absolutely no sense to me to go do this.”

While crowdfunding helped Thimbleweed Park years ago, Gilbert says Kickstarter is “basically dead these days as a way of funding games.”

For point-and-click adventure Thimbleweed Park, Gilbert got around a similar problem in part by going directly to fans of the genre, raising $600,000 of a $375,000 goal via crowdfunding. But even then, Gilbert said that private investors needed to provide half of the game’s final budget to get it over the finish line. And while Gilbert said he’d love to revisit the world of Thimbleweed Park, “I just don’t know where I’d ever get the money. It’s tougher than ever in some ways… Kickstarter is basically dead these days as a way of funding games.”

Compared to the start of his career, Gilbert said that today’s big-name publishers “are very analytics-driven. The big companies, it’s like they just have formulas that they apply to games to try to figure out how much money they could make, and I think that just in the end you end up giving a whole lot of games that look exactly the same as last year’s games, because that makes some money.

“When we were starting out, we couldn’t do that because we didn’t know what made this money, so it was, yeah, it was a lot more experimenting,” he continued. “I think that’s why I really enjoy the indie game market because it’s kind of free of a lot of that stuff that big publishers bring to it, and there’s a lot more creativity and you know, strangeness, and bizarreness.”

Run for it

After a period where Gilbert said he “was kind of getting a little down” about the failure of his action-RPG project, he thought about circling back to a funny little prototype he developed as part of a 2019 game design meet-up organized by Spry Fox’s Daniel Cook. That prototype—initially simply called “Runner”—focused on outrunning the bottom of a continually scrolling screen, picking up ammo-limited weapons to fend off enemies as you did.

While the prototype initially required players to aim at those encroaching enemies as they ran, Gilbert said that the design “felt like cognitive overload.” So he switched to an automatic aiming and firing system, an idea he says was part of the prototype long before it became popularized by games like Vampire Survivors. And while Gilbert said he enjoyed Vampire Survivors, he added that the game’s style was “a little too much ‘ADHD’ for me. I look at those games and it’s like, wow, I feel like I’m playing a slot machine at some level. The flashing and upgrades and this and that… it’s a little too much.”

The 2019 “Runner” prototype that would eventually become Death by Scrolling.

But Gilbert said his less frenetic “Runner” prototype “just turned out to be a lot of fun, and I just played it all the time… It was really fun for groups of people to play, because one person will play and other people would kind of be laughing and cheering as you, you know, escape danger at the nick of time.”

Gilbert would end up using much of the art from his scrapped RPG project to help flesh out the “Runner” prototype into what would eventually become Death by Scrolling. But even late in the game’s development, Gilbert said the game was missing a unifying theme. “There was no reason initially for why you were doing any of this. You were just running, you know?”

That issue didn’t get solved until the last six months of development, when Gilbert hit on the idea of running through a repeating purgatory and evading Death, in the form of a grim reaper that regularly emerges to mercilessly hunt you down. While you can use weapons to temporarily stun Death, there’s no way to completely stop his relentless pursuit before the end of a stage.

That grim reaper really puts the Death in Death by Scrolling.

“Because he can’t be killed and because he’s an instant kill for you, it’s a very unique thing you really kinda need to avoid,” Gilbert said. “You’re running along, getting gold, gaining gems, and then, boom, you hear that [music], and Death is on the screen, and you kind of panic for a moment until you orient yourself and figure out where he is and where he’s coming from.”

Is anyone reading this?

After spending so much of his career on slow-burn adventure games, Gilbert admitted there were special challenges to writing for an action game—especially one where the player is repeating the same basic loop over and over. “It’s a lot harder because you find very quickly that a lot of players just don’t care about your story, right? They’re there to run, they’re there to shoot stuff… You kind of watch them play, and they’re just kind of clicking by the dialogue so fast that they don’t even see it.”

Surprisingly, though, Gilbert said he’s seen that skip-the-story behavior among adventure game players, too. “Even in Thimbleweed Park and Monkey Island, people still kind of pound through the dialogue,” he said. “I think if they think they know what they need to do, they just wanna skip through the dialogue really fast.”

As a writer, Gilbert said it’s “frustrating” to see players doing the equivalent of “sitting down to watch a movie and just fast forwarding through everything except the action parts.” In the end, though, he said, a game developer has to accept that not everyone is playing for the same reasons.

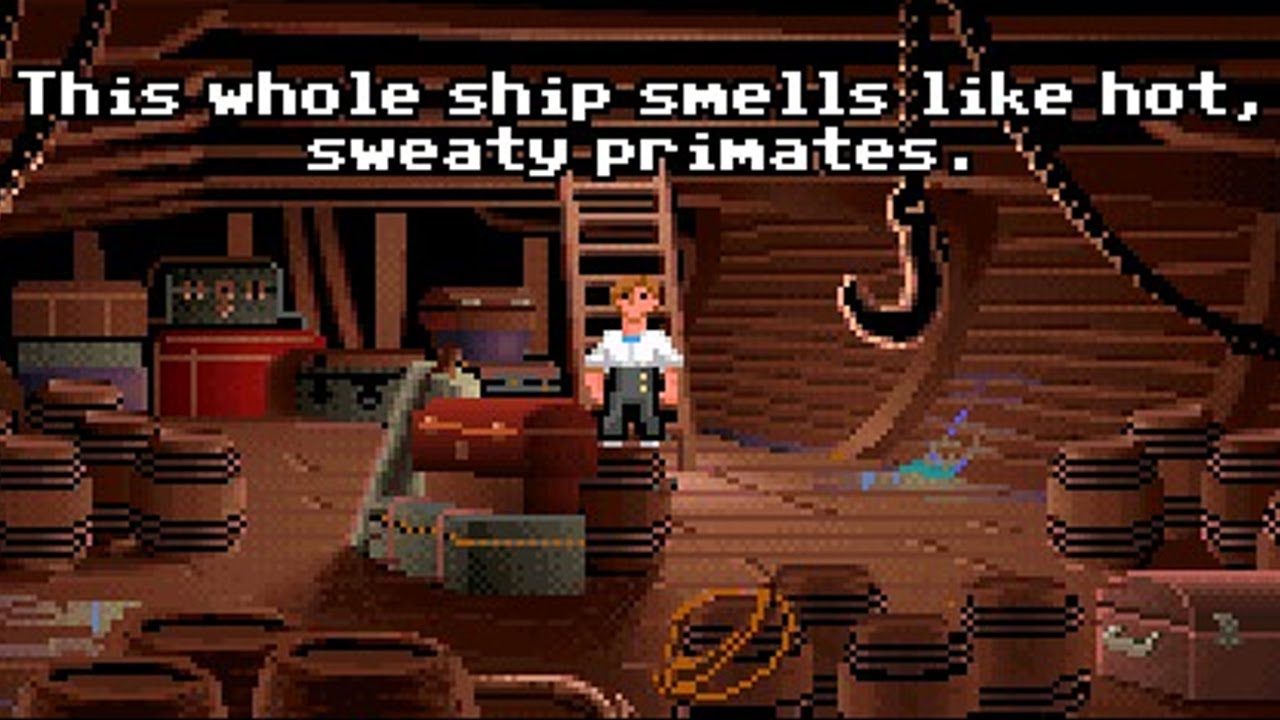

Believe it or not, some players just breeze past quality dialogue like this. Credit: LucasArts

“There’s a certain percentage of people who will follow the story and enjoy it, and that’s OK,” he said. “And everyone else, if they skip the story, it’s got to be OK. You need to make sure you don’t embed things deep in the story that are critical for them to understand. It’s a little bit like really treating the story as truly optional.”

Those who do pay attention to the story in Death by Scrolling will come across what Gilbert said he hoped was a less-than-subtle critique of the capitalist system. That critique is embedded in the gameplay systems, which require you to collect more and more gold—and not just two pennies on your eyes—to pay a newly profit-focused River Styx ferryman that has been acquired by Purgatory Inc.

“It’s purgatory taken over by investment bankers,” Gilbert said of the conceit. “I think a lot of it is looking at the world today and realizing capitalism has just taken over, and it really is the thing that’s causing the most pain for people. I just wanted to really kind of drive that point in the game, in a kind of humorous, sarcastic way, that this capitalism is not good.”

While Gilbert said he’s always harbored these kinds of anti-capitalist feelings “at some level,” he said that “certainly recent events and recent things have gotten me more and more jumping on the ‘Eat the Rich’ bandwagon.” Though he didn’t detail which “recent events” drove that realization, he did say that “billionaires and all this stuff… I think are just causing more harm than good.”

Is the point-and-click adventure doomed?

Despite his history with point-and-click adventures, and the relative success of Thimbleweed Park less than 10 years ago, Gilbert says he isn’t interested in returning to the format popularized by LucasArts’ classic SCUMM Engine games. That style of “use verb on noun” gameplay is now comparable to a black-and-white silent movie, he said, and will feel similarly dated to everything but a niche of aging, nostalgic players.

“You do get some younger people that do kind of enjoy those games, but I think it’s one of those things that when we’re all dead, it probably won’t be the kind of thing that survives,” he said.

Gilbert says modern games like Lorelei and the Laser Eyes show a new direction for adventure games without the point-and-click interface.

But while the point-and-click interface might be getting long in the tooth, Gilbert said he’s more optimistic about the future of adventure games in general. He points to recent titles like Blue Prince and Lorelei and the Laser Eyes as examples of how clever designers can create narrative-infused puzzles using modern techniques and interfaces. “I think games like that are kind of the future for adventure games,” he said.

If corporate owner Disney ever gave him another chance to return to the Monkey Island franchise, Gilbert said he’d like to emulate those kinds of games by having players “go around in a true 3D world, rather than as a 2D point-and-click game… I don’t really know how you would do the puzzle solving in [that] way, and so that’s very interesting to me, to be able to kind of attack that problem of doing it in a 3D world.”

After what he said was a mixed reception to the gameplay changes in Return to Monkey Island, though, Gilbert allowed that franchise fans might not be eager for an even greater departure from tradition. “Maybe Monkey Island isn’t the right game to do as an adventure game in a 3D world, because there are a lot of expectations that come with it,” he said. “I mean if I was to do that, you just ruffle even more feathers, right? There’s more people that are very attached to Monkey Island, but more in its classic sense.”

Looking over his decades-long career, though, Gilbert also noted that the skills needed to promote a new game today are very different from those he used in the 1980s. “Back then, there were a handful of print magazines, and there were a bunch of reporters, and you had sent out press releases… That’s just not the way it works today,” he said. Now, the rise of game streamers and regular YouTube game development updates has forced game makers to be good on camera, much like MTV did for a generation of musicians, Gilbert said.

“The [developers] that are successful are not necessarily the good ones, but the good ones that also present well on YouTube,” he said. “And you know, I think that’s kind of a problem, that’s a gate now… In some ways, I think it’s too bad because as a developer, you have to be a performer. And I’m not a performer, right? If I was making movies, I would be a director, not an actor.”

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.