What do people actually use ChatGPT for? OpenAI provides some numbers.

Hey, what are you doing with that?

New study breaks down what 700 million users do across 2.6 billion daily GPT messages.

A live look at how OpenAI gathered its user data. Credit: Getty Images

As someone who writes about the AI industry relatively frequently for this site, there is one question that I find myself constantly asking and being asked in turn, in some form or another: What do you actually use large language models for?

Today, OpenAI’s Economic Research Team went a long way toward answering that question, on a population level, releasing a first-of-its-kind National Bureau of Economic Research working paper (in association with Harvard economist David Denning) detailing how people end up using ChatGPT across time and tasks. While other research has sought to estimate this kind of usage data using self-reported surveys, this is the first such paper with direct access to OpenAI’s internal user data. As such, it gives us an unprecedented direct window into reliable usage stats for what is still the most popular application of LLMs by far.

After digging through the dense 65-page paper, here are seven of the most interesting and/or surprising things we discovered about how people are using OpenAI today.

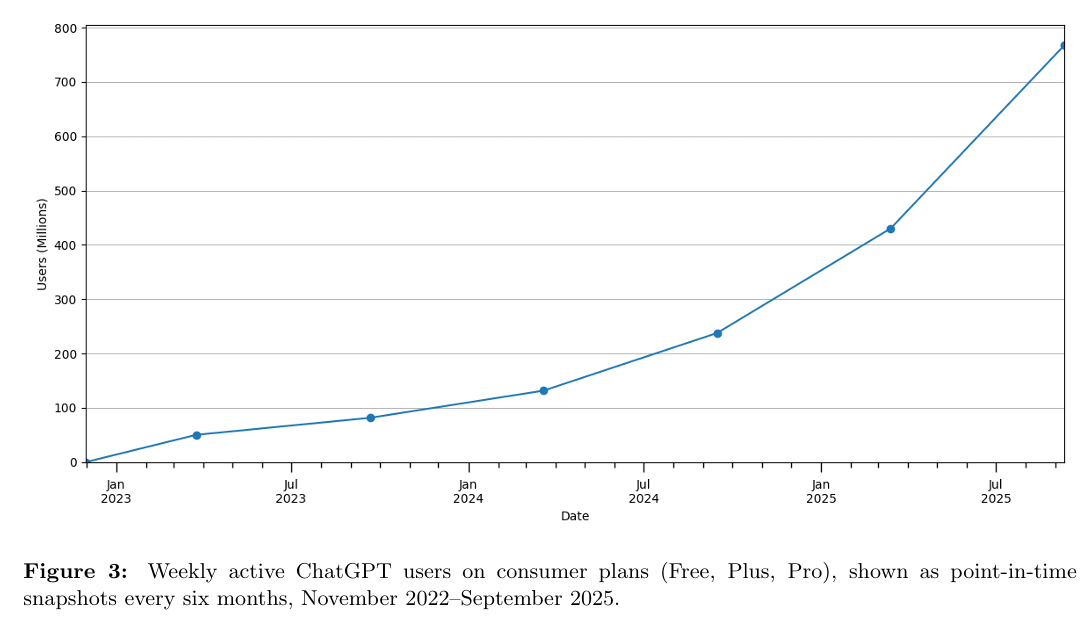

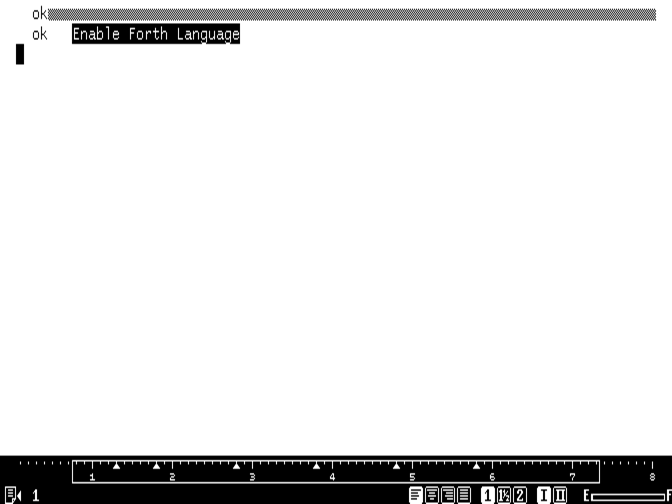

OpenAI is still growing at a rapid clip

We’ve known for a while that ChatGPT was popular, but this paper gives a direct look at just how big the LLM has been getting in recent months. Just measuring weekly active users on ChatGPT’s consumer plans (i.e. Free, Plus, and Pro tiers), ChatGPT passed 100 million users in early 2024, climbed past 400 million users early this year, and currently can boast over 700 million users, or “nearly 10% of the world’s adult population,” according to the company.

Line goes up… and faster than ever these days. Credit: OpenAI

OpenAI admits its measurements might be slightly off thanks to double-counting some logged-out users across multiple individual devices, as well as some logged-in users who maintain multiple accounts with different email addresses. And other reporting suggests only a small minority of those users are paying for the privilege of using ChatGPT just yet. Still, the vast number of people who are at least curious about trying OpenAI’s LLM appears to still be on the steep upward part of its growth curve.

All those new users are also leading to significant increases in just how many messages OpenAI processes daily, which has gone up from about 451 million in June 2024 to over 2.6 billion in June 2025 (averaged over a week near the end of the month). To give that number some context, Google announced in March that it averages 14 billion searches per day, and that’s after decades as the undisputed leader in Internet search.

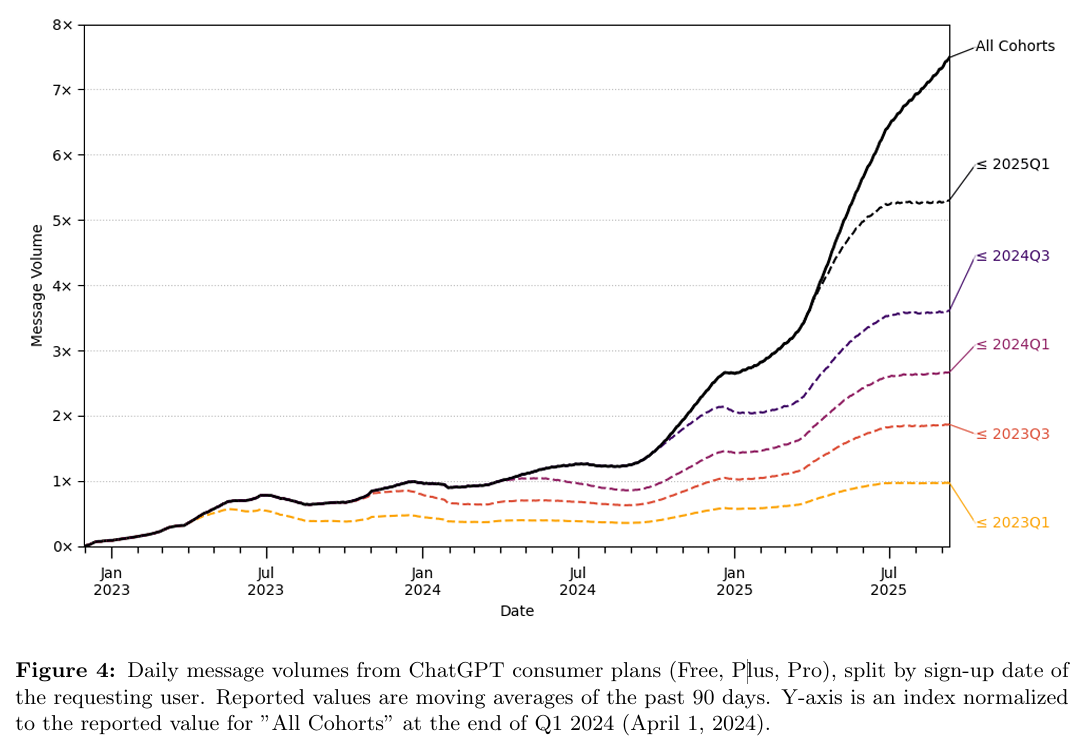

… but usage growth is plateauing among long-term users

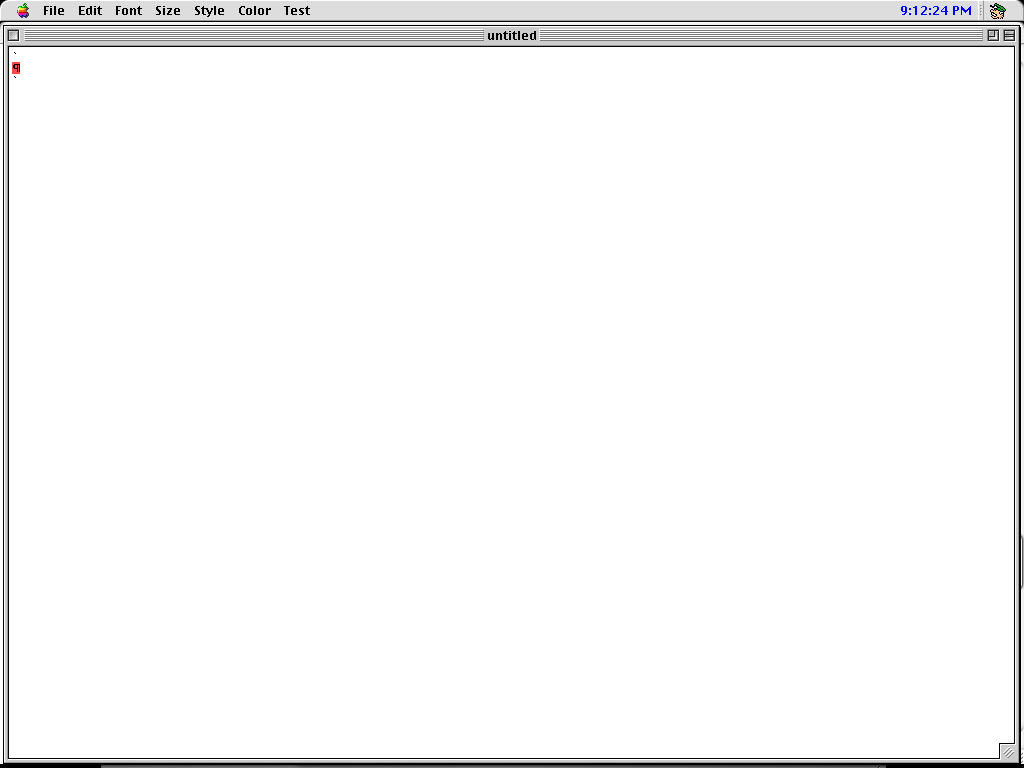

Newer users have driven almost all of the overall usage growth in ChatGPT in recent months. Credit: OpenAI

In addition to measuring overall user and usage growth, OpenAI’s paper also breaks down total usage based on when its logged-in users first signed up for an account. These charts show just how much of ChatGPT’s recent growth is reliant on new user acquisition, rather than older users increasing their daily usage.

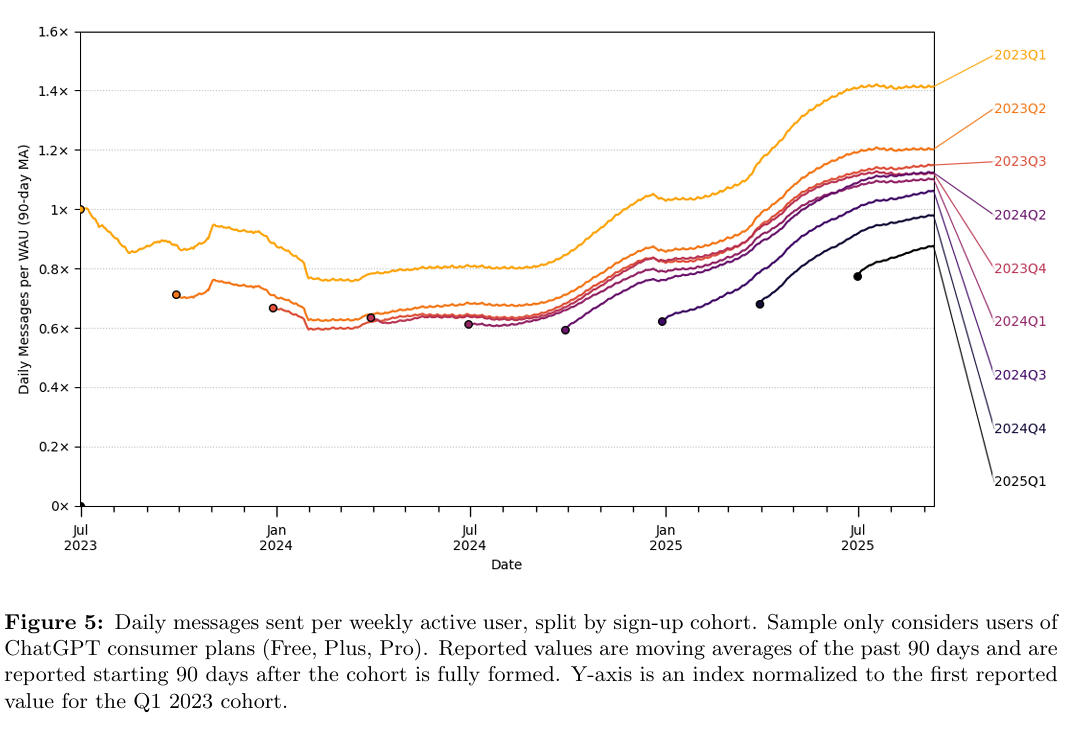

In terms of average daily message volume per individual long-term user, ChatGPT seems to have seen two distinct and sharp growth periods. The first runs roughly from September through December 2024, coinciding with the launch of the o1-preview and o1-mini models. Average per-user messaging on ChatGPT then largely plateaued until April, when the launch of the o3 and o4-mini models caused another significant usage increase through June.

Since June, though, per-user message rates for established ChatGPT users (those who signed up in the first quarter of 2025 or before) have been remarkably flat for three full months. The growth in overall usage during that last quarter has been entirely driven by newer users who have signed up since April, many of whom are still getting their feet wet with the LLM.

Average daily usage for long-term users has stopped growing in recent months, even as new users increase their ChatGPT message rates. Credit: OpenAI

We’ll see if the recent tumultuous launch of the GPT-5 model leads to another significant increase in per-user message volume averages in the coming months. If it doesn’t, then we may be seeing at least a temporary ceiling on how much use established ChatGPT users get out of the service in an average day.

ChatGPT users are younger and were more male than the general population

While young people are generally more likely to embrace new technology, it’s striking just how much of ChatGPT’s user base is made up of our youngest demographic cohort. A full 46 percent of users who revealed their age in OpenAI’s study sample were between the ages of 18 and 25. Add in the doubtless significant number of people under 18 using ChatGPT (who weren’t included in the sample at all), and a decent majority of OpenAI’s users probably aren’t old enough to remember the 20th century firsthand.

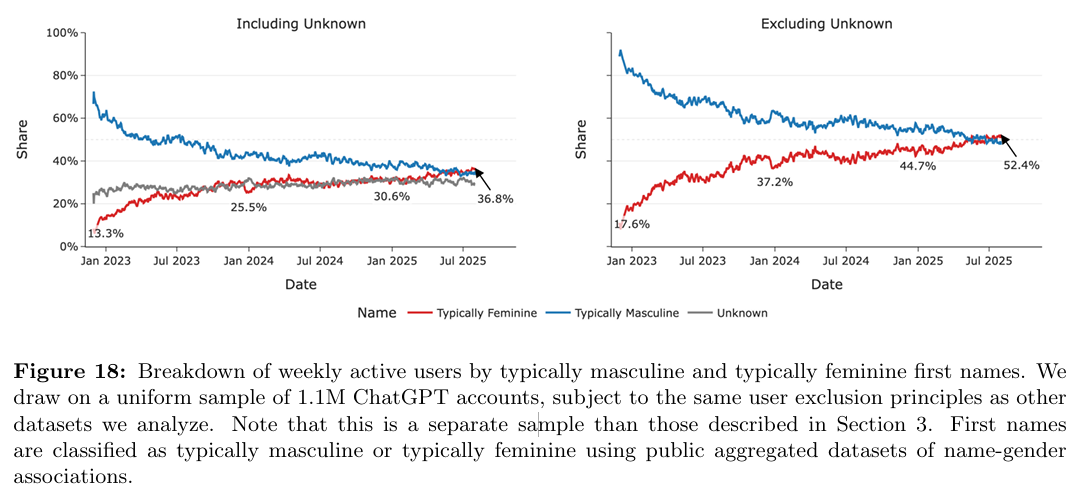

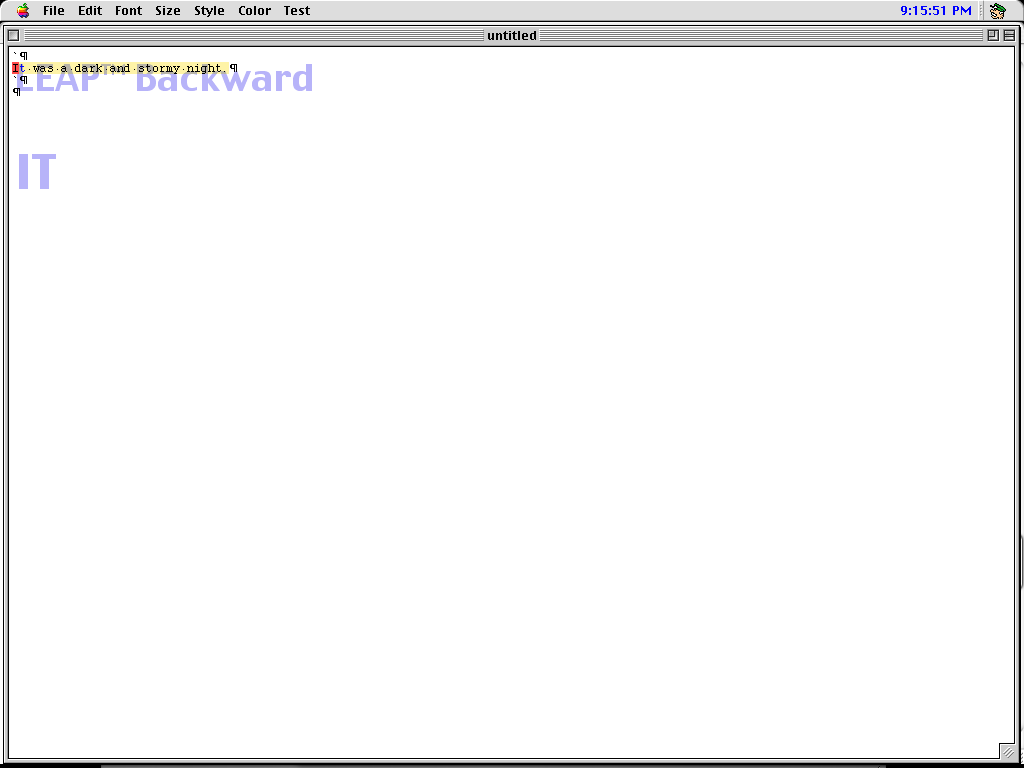

What started as mostly a boys’ club has reached close to gender parity among ChatGPT users, based on gendered name analysis. Credit: OpenAI

OpenAI also estimated the likely gender split among a large sample of ChatGPT users by using Social Security data and the World Gender Name Registry‘s list of strongly masculine or feminine first names. When ChatGPT launched in late 2022, this analysis found roughly 80 percent of weekly active ChatGPT users were likely male. In late 2025, that ratio has flipped to a slight (52.4 percent) majority for likely female users.

People are using it for more than work

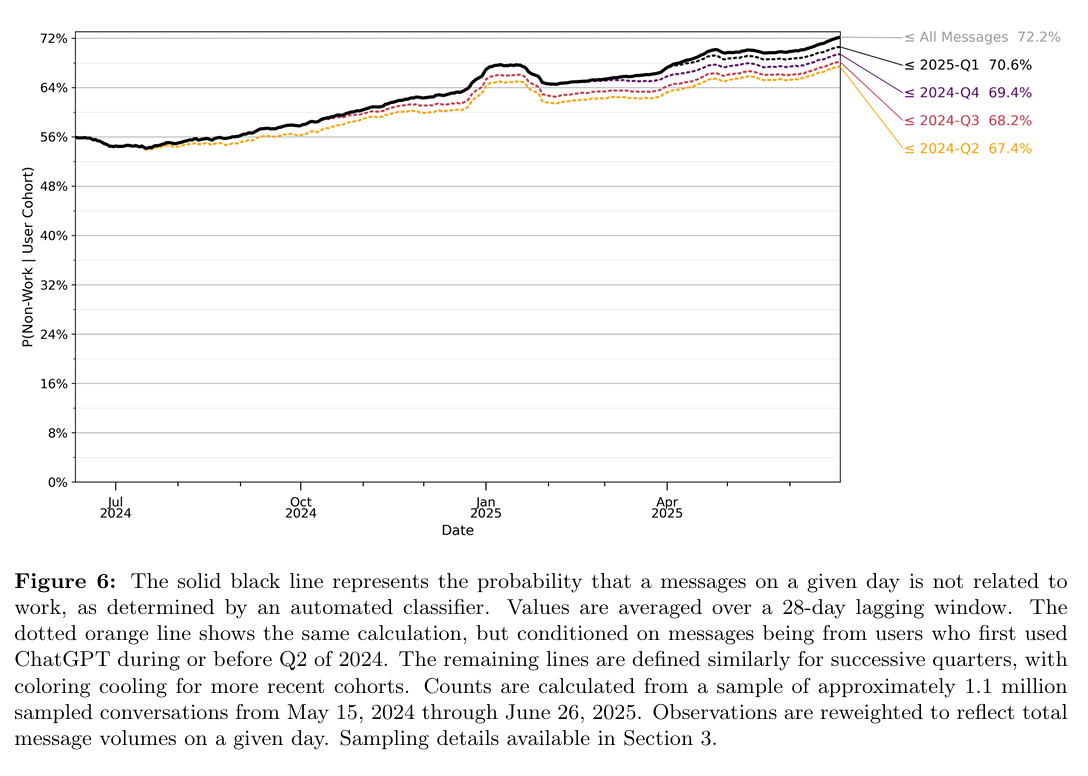

Despite all the talk about LLMs potentially revolutionizing the workplace, a significant majority of all ChatGPT use has nothing to do with business productivity, according to OpenAI. Non-work tasks (as identified by an LLM-based classifier) grew from about 53 percent of all ChatGPT messages in June of 2024 to 72.2 percent as of June 2025, according to the study.

As time goes on, more and more ChatGPT usage is becoming non-work related. Credit: OpenAI

Some of this might have to do with the exclusion of users in the Business, Enterprise, and Education subscription tiers from the data set. Still, the recent rise in non-work uses suggests that a lot of the newest ChatGPT users are doing so more for personal than for productivity reasons.

ChatGPT users need help with their writing

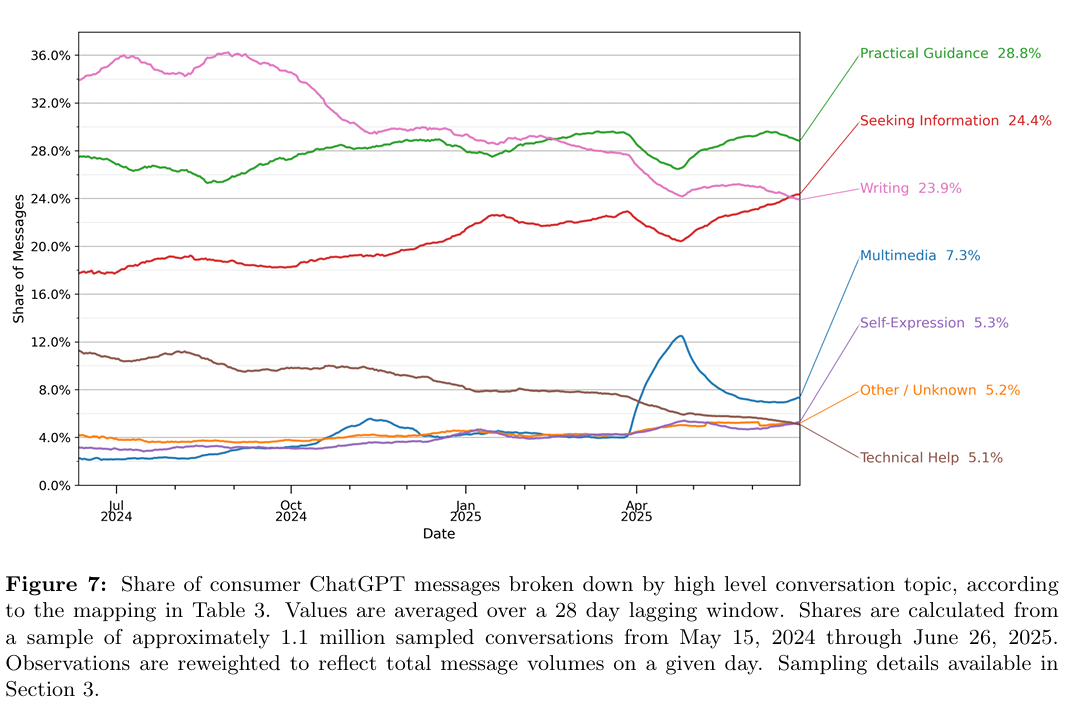

It’s not that surprising that a lot of people use a large language model to help them with generating written words. But it’s still striking the extent to which writing help is a major use of ChatGPT.

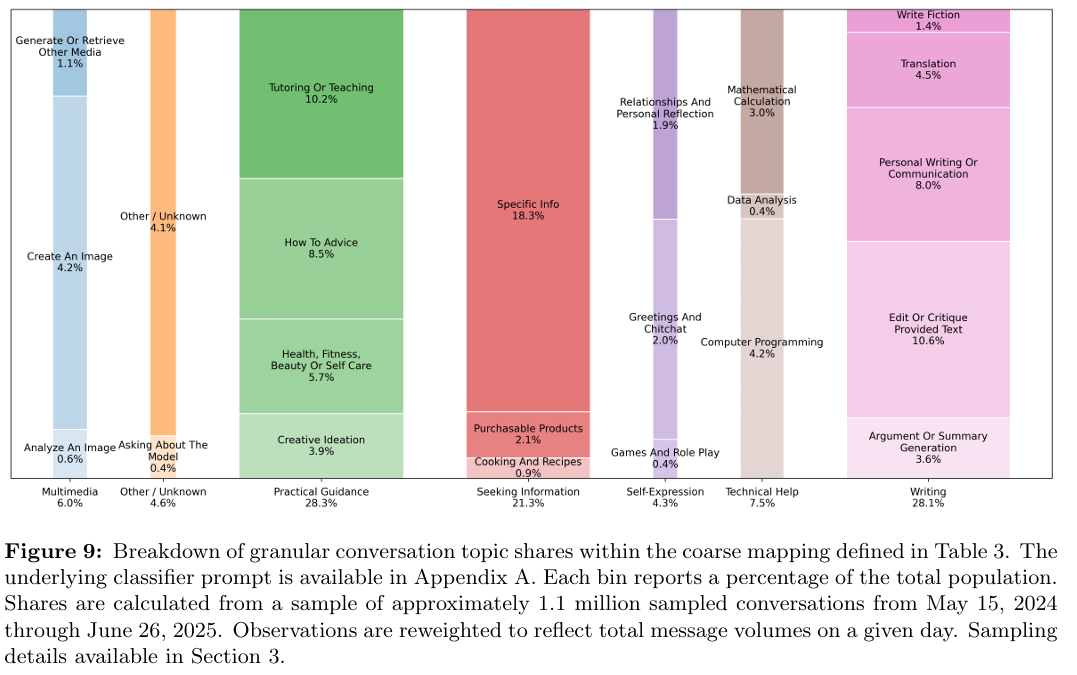

Across 1.1 million conversations dating from May 2024 to June 2025, a full 28 percent dealt with writing assistance in some form or another, OpenAI said. That rises to a whopping 42 percent for the subset of conversations tagged as work-related (by far the most popular work-related task), and a majority, 52 percent, of all work-related conversations from users with “management and business occupations.”

A lot of ChatGPT use is people seeking help with their writing in some form. Credit: OpenAI

OpenAI is quick to point out, though, that many of these users aren’t just relying on ChatGPT to generate emails or messages from whole cloth. The percent of all conversations studied involves users asking the LLM to “edit or critique” text, at 10.6 percent, vs. just 8 percent that deal with generating “personal writing or communication” from a prompt. Another 4.5 percent of all conversations deal with translating existing text to a new language, versus just 1.4 percent dealing with “writing fiction.”

More people are using ChatGPT as an informational search engine

In June 2024, about 14 percent of all ChatGPT conversations were tagged as relating to “seeking information.” By June 2025, that number had risen to 24.4 percent, slightly edging out writing-based prompts in the sample (which had fallen from roughly 35 percent of the 2024 sample).

A growing number of ChatGPT conversations now deal with “seeking information” as you might do with a more traditional search engine. Credit: OpenAI

While recent GPT models seem to have gotten better about citing relevant sources to back up their information, OpenAI is no closer to solving the widespread confabulation problem that makes LLMs a dodgy tool for retrieving facts. Luckily, fewer people seem interested in using ChatGPT to seek information at work; that use case makes up just 13.5 percent of work-related ChatGPT conversations, well below the 40 percent that are writing-related.

A large number of workers are using ChatGPT to make decisions

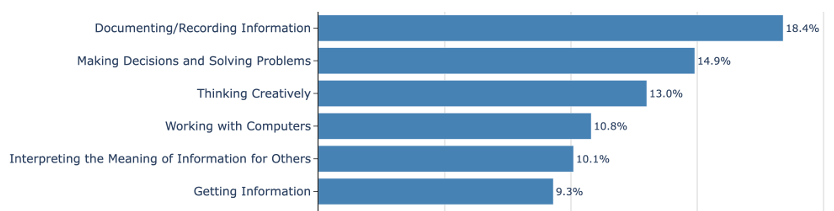

Among work-related conversations, “making decisions and solving problems” is a relatively popular use for ChatGPT. Credit: OpenAI

Getting help editing an email is one thing, but asking ChatGPT to help you make a business decision is another altogether. Across work-related conversations, OpenAI says a significant 14.9 percent dealt with “making decisions and solving problems.” That’s second only to “documenting and recording information” for work-related ChatGPT conversations among the dozens of “generalized work activity” categories classified by O*NET.

This was true across all the different occupation types OpenAI looked at, which the company suggests means people are “using ChatGPT as an advisor or research assistant, not just a technology that performs job tasks directly.”

And the rest…

Some other highly touted use cases for ChatGPT that represented a surprisingly small portion of the sampled conversations across OpenAI’s study:

- Multimedia (e.g., creating or retrieving an image): 6 percent

- Computer programming: 4.2 percent (though some of this use might be outsourced to the API)

- Creative ideation: 3.9 percent

- Mathematical calculation: 3 percent

- Relationships and personal reflection: 1.9 percent

- Game and roleplay: 0.4 percent

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.

What do people actually use ChatGPT for? OpenAI provides some numbers. Read More »