There’s quite a lot in the queue since last time, so this is the first large chunk of it, which focuses on apps and otherwise finding an initial connection, and some things that directly impact that.

-

You’re Single Because You Have No Friends To Date.

-

You’re Single Because You Aren’t Willing To Be Dungeon Master.

-

You’re Single Because You Didn’t Listen To My Friend’s Podcast.

-

You’re Single Because You Flunk The Eye Contact Test.

-

You’re Single Because The Women Don’t Hit On The Men.

-

You’re Single Because When A Woman Did Hit On You, You Choked.

-

You’re Single Because You Don’t Know The Flirtation Escalation Ladder.

-

You’re Single Because You Will Actually Never Open.

-

You’re Single Because We Let Tinder Win.

-

You’re Single Because The Apps Are Bad On Purpose To Make You Click.

-

You’re Single Because You Present Super Weird.

-

You’re Single Because You Have The Wrong Hobbies.

-

You’re Single Because You Do The Wrong Kind Of Magic.

-

You’re Single And All That Rejection Really Sucks.

-

You’re Single Because Dating Apps Are Designed Like TikTok.

-

You’re Single And Here’s Aella With a Tea Update.

-

You’re Single Because You Don’t Have a Date Me Doc.

-

You’re Single Because You Didn’t Hire a Matchmaker.

Two thirds of romantic partners were friends first, especially at university.

Paula Ghete: Does this mean that a degree of concern is warranted that platonic friendships between people of the opposite sex can turn into an actual relationship one day (or an affair)? As far as I know, men tend to choose female friends who are attractive.

William Costello: Yes!

Two thirds really is an awful lot. It’s enough of an awful lot to suggest that if your current goal is a long term relationship rather than short term dating, and you have enough practice, it might outright be a mistake to be primarily (rather than opportunistically or additionally, the goods are often non-rivalrous) trying to date people who aren’t your friends or at least friends of friends? That instead you should focus on making platonic friends with people you find attractive, without trying to date them at all, and then see what happens?

Highly speculative, but potentially this has a lot of advantages, including a network that can lead to dates with non-friends. It’s pretty great to have friends even if there are never any non-platonic benefits.

It does have its own difficulties. The most obvious one is that if you’re not trying to date them, you need a different excuse and set of activities in order to become friends.

As the paper notes, this raises the question of why we so often have the opposite impression, or that the youth think that hitting on your friends is just awful – although perhaps they do think that in cases where it doesn’t work, there’s no contradiction there, if you can’t do subtle escalations instead then one could say that’s a skill issue.

There’s also ‘an app for that’ at least inside the rationalist community, called Reciprocity, where you can signal interest and then it only reveals if there is a two-sided match. If this is your strategy it is important social tech to minimize the amount to which you make it weird.

Friendmaxxing makes it a lot easier to try to take that leap. If you have one friend and you make it weird, then you might have zero friends. If you have a thousand friends, you have not one friend to spare, but also if you botch things and go down to 999 friends you will be fine.

One note in the paper is that if you move to friends with benefits, that typically doesn’t lead to long term romantic success. If you want something more, then statistically you need to go straight for it once things get complicated.

Two strong pieces of advice here.

Kelsey Piper: I try to stay out of the dating discourse because it’s obnoxious to hear from happily married lesbians about the state of gender relations but there is such a lane for someone giving advice like ‘meet single men by running a killer D&D game’ and ‘try getting really into aviation’

A lot of people suck at talking about themselves but in fact have deeply felt values and fascinations and if you meet them there, they’re very very cool. Don’t give up on really Getting someone, but don’t try to achieve it by asking them personality questions.

The first half is a gimme. If there is an activity that is popular with the gender you’re looking for, where the people who want to do it are people you would want to date, then running or helping run such an activity is a great idea, even better than simply participating, and actually making it a killer version is even better. I do not think this in any way counts as being ‘fake.’

This goes double when combined with the statistics about friends. D&D is the ultimate ‘make friends first’ strategy.

The second half is even better. Traditional dating paths require or at least tend to cause a set of strange, awkward conversations about personality and dating. That means the people who are good at navigating that will be in high demand, whereas those who are not as good will struggle. Any way to change the topic into other things shakes that up and puts you in a better spot. It might be a bit slower, but you absolutely get to know people when not explicitly discussing getting to know them.

Also, do this with your friends. Knowing your friends this way is Amazingly Great, on its own merits.

My old friend Ted Knutson has a new podcast called Man Down, which includes at least three episodes on dating. This one is about strategy using dating apps and improving your profile, the first one was more about dating in general, they then followed up with another on fixing your profile.

I wouldn’t have listened if I hadn’t had the extra value of watching Ted squirm. The information density from podcasts isn’t great even at faster speeds, although the info that is here seems pretty solid if you don’t mind that.

There’s a bunch of fun stats to start. The first recommendation is for men to fight on different terrain where they aren’t unnumbered (men outnumber women ~4:1 on Tinder and spend ~96% of the money) or in a bad spot, try in person. But you might fully not have that option so they mostly focus on sharing data and then improving Ted’s dating profile. Women on Tinder swipe right 8% of the time, men swipe right 46% of the time, the average man gets 1-2 matches a week. Hinge’s numbers are less unbalanced (2:1 ratio). They discuss various different apps you can consider.

Then the Ted squirming part begins and we start on his profile. It’s remarkable how bad it starts out, starting with pictures. Some advice given: Think elegant and sober, charismatic pictures, focus on face, definitely not shirtless unless maybe you’re playing sports, ideally pay to get better photos taken. Save the humor for the prompts and chats and focus answers on the person not the relationship type. Actively study profiles before you message people, customize everything.

This seems right.

Sasha Chapin: There is an eye contact dance that happens in the first few seconds when single men and women meet and if a man flunks it, it’s actually tricky to come back from.

So my advice to single guys is, become someone who automatically aces it because you feel fundamentally safe in the world.

[You want to use] whatever pattern of eye contact conveys the message “I’m okay with you noticing that I’m attracted to you, whatever happens next isn’t a problem for me” — not hiding, not grabby, centered, not managing the response on the other end.

This probably doesn’t mean unbroken staring unless the other party defaults to intense eye contact.

The question is, is this a ‘sincerity is great, once you can fake that you’ve got it made’ situation? Or is it easier and more effective to actually be okay with all of this?

The good news is that it is optimal life strategy to genuinely be okay with whatever happens next so long as no machetes are involved. It is actively good for other people you are attracted to to sense you are attracted to them – so long as they sense that you’re okay with whatever happens next, and that you aren’t afraid of them knowing.

The other good news is that you can also pass through practice, even if you’re not fully genuinely okay with whatever happens next short of machetes.

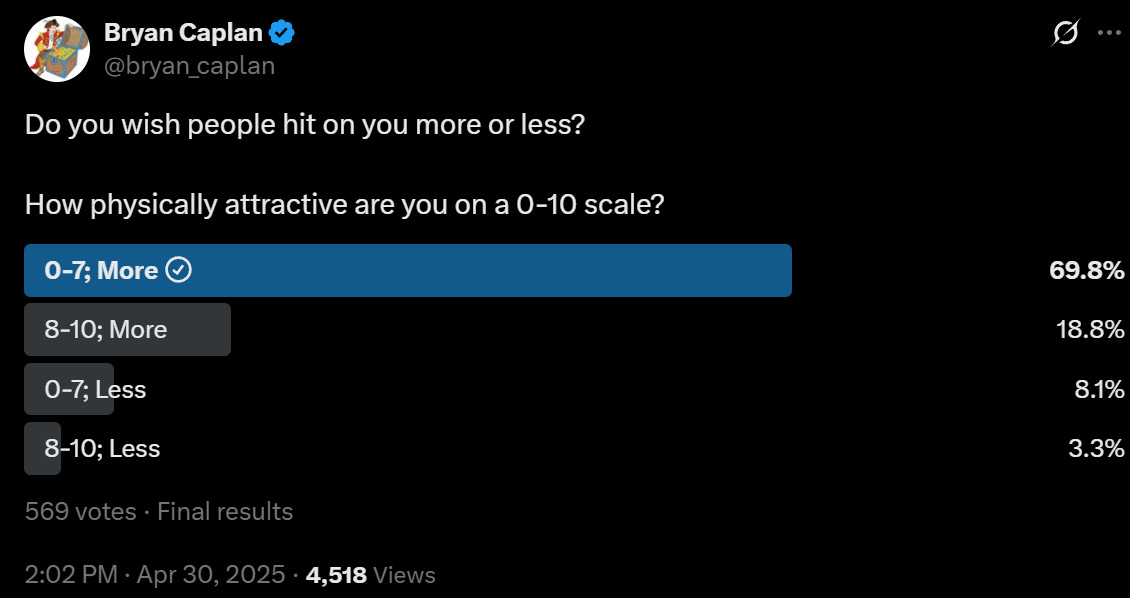

Bryan Caplan’s polls are mostly answered by men, so:

There was essentially no interaction between the variables. About 85% of those in both groups wanted to be hit on more rather than less. Even when it’s an automatic no, you know what, it’s nice to be asked.

RFH Doctor: I love how girls will never tell a man she’s interested in him, instead they send secret signals through tweets, instagram stories, brain waves, magic rituals, and prayers, ancient feminine wisdom that ensures only men who are in tune with the unconscious will be selected.

Dr. Jen Izaakson: Also can I just say, as a lesbian, the subtle signals women send are hardly a difficult set of hieroglyphics to decode. What men find especially difficult is not only the reading of the signs, but also not overstepping or not taking the route she wants in the pursuit. Yes this woman likes you, but she doesn’t want you to escalate proximity beyond her pace. Men need to learn to drive the wheel exactly how the map holder suggest.

Napoleonos: Literally anything except telling him.

RFH: I love that for us <3

So, you seem to be saying ‘shit test’ like that’s a bad thing…

eigenrobot: men often misinterpret this as a “shit test” or something but in fact a potential partner’s ability to read her mind is a completely reasonable selection criterion for women to prioritize.

and “I am falling over myself to psychically telegraph that i am interested” is easy mode!

all you have to do is _pay attention_ to women and what they’re doing and be marginally reflective about it

easy top three highest ROI skill available to young men

corsaren: Too many men treat it as a crazy demand, but not only is partner mind-reading totally doable if you have a strong bond, it’s also very fun once you get good at it. Bonus: once you prove that you can read her mind, she’ll be more likely to explain in the times when you can’t.

There’s nothing inherently bad or inefficient about a shit test. This is very clearly a (very standard) shit test. Anything that could be described by the phrase ‘not fing telling you’ is either a ghosting or a shit test. It’s selection and information gathering via forcing you to correctly respond to an uncertain situation, which here involves both ‘figure out she’s interested’ and also ‘actually act on it’ and doing that in a skilled fashion.

Which has some very clear positive selection effects. But it also has a clear negative selection effect for ‘men who go around hitting on everyone a lot’ and against men who are (very understandably and often for good reasons) risk averse about making such a move.

It is my understanding is that as things have shifted, with more men being afraid to open either in general or to anyone they already know, this is making a lot less sense as a filter.

The problem with not doing so is you are filtering a lot less for ability to detect attraction and mind reading, and far more for those who have norms that involve hitting on a lot of women. Which is a far more mixed blessing. You’re going to fail on a lot more otherwise desirable connections than you would have in the past.

A man being unwilling to make a first move simply isn’t a strong negative sign at this point. Indeed, if they are capable of navigating subsequent moves it could even be a positive sign, because this is how they didn’t get removed from the market.

Also I am pretty sure the other downsides of being too forward are way down from where they used to be. That is especially true if they are unwilling to (essentially ever) make the first move, which means they’re likely to very much appreciate it when you do so instead (and if they don’t, then the combination is a big red flag). Thus, I think being forward (as a woman seeking men) is a far better strategy than it was in the past.

If someone runs a TikTok experiment where a woman hits on men out of the blue, do you get points for being smooth and trying to capitalize on it, or points for correctly suspecting it’s not real?

Richard Hanania: Fascinating social experiment here. Watched the whole thing. You can see the variation in men’s confidence and the differences are absolutely vast. Best performing was black guy in black tank top, the worst was the first guy. Just completely different levels of being able to capitalize on an opportunity.

I looked at the replies finally, so many of you are so pathetic. You should have a positive attitude and even if it’s a skit there’s still opportunity there. You could win her over or could even impress others in the vicinity! At worst you can practice talking to an attractive woman. And you shouldn’t walk around with an attitude of nothing good can ever happen to me anyway.

I just keep being shocked by how unworthy of existence many of you are. It was outside my realm of imagination. Now I know what women feel. You all think like this and think you deserve companionship or even to live.

Cartoons Hate Her: Most men are hit on so rarely that the ones who aren’t top-tier attractive immediately know something is going on lol. You can see them looking for whoever is filming.

Side note: I had no idea it was this easy to hit on men. I have never approached a man, I found it unbecoming. I can see why men are afraid of it.

Richard Hanania: It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Cartoons Hate Her: True.

Armand Domalewski: The way she does it is so obviously fake lol

It’s a guy’s idea of how a girl would hit on a guy.

Lazy River:

>guy thinking “this has to be fake”

>it is in fact fake

Birth of another super villain. This happens to guys fr while the girls friends laugh in the back ground and it takes them out of the game for years, sometimes the rest of their lives. And it is this easy to pick up a man.

David: They’re objectively correct that there’s a camera tho, that’s not them being stupid for lacking confidence they are 100% right that she’s not to be trusted.

Rob Henderson: Reminds me of a study years ago where researchers had attractive actors to go up to people on a college campus and ask if they’d like to go on a date with them, if they’d like to go back to their apartment with them, and if they’d like to go to bed with them.

For women, 56% said yes to the date with the attractive male stranger, 6% said yes to going back to his apartment, and zero said they would go to bed with him.

For men, half said yes to the date with the attractive female stranger, 69% said yes to going to her apartment, and 75% said yes to going to bed with her.

If you know you’re being filmed that’s all the more reason to go for it? Same principle as before, if they post it and it gets views you identify yourself and say DMs are open.

All the men in the video did successfully exchange contact information of some form. Rob Henderson and Richard Hanania then did a 20 minute analysis of the 5 minute video, critiquing the various responses to see who got game and who didn’t.

They pointed out correctly that the percentage play, if you have the option and you are actually interested and think this could be real, is to attempt escalation to a low investment date on the spot, and go from there, while she’s feeling it.

The other great point is, no it isn’t real by design, but who is to say you cannot make it real? She’s opening. She’s giving you an opportunity. Sure, she might intend it to purely be a bit, but if you play your cards right, who knows? Worst case scenario is you get an extra rep. It’s even a power move to indicate you know she thinks it’s fake, and to run right through that.

I would add that the men here all now have her contact information, and there is nothing stopping them from extending the experiment. As in, you say ‘I know that your approaching me was a bit for a video, but I do like you, so…’ and again worst case is she tells the world you tried to have some game. Even now, there’s still time, guys.

Also, of course, yes women can basically do this at will, and there are strong arguments that they should be approaching quite a lot, as they have full social permission to do so, and even when you get a no you probably brighten the guy’s day – almost all guys consistently say, as noted above, they want to be approached more. And as I noted above, ‘guy is willing to open’ is not a great selection plan in 2025.

Even basic flirting principles are in short supply so it’s worth going over this again, starting from the top.

Chase Harris: If you subtly flirt with every woman you come across and say wassup bro in a happy mood to random dudes you will go far in life. Everyone is like a kid trapped in an adult body. They just want compliments and friends, so be that. You’ll never spend a day broke or alone if you do.

Standard Deviant offers us The Escalation Ladder. The flirting examples are sometimes weird and strangely ordered, but the principles are what is important and seem entirely correct. Indeed, the very fact that the details seem off yet this is still the person writing the post illustrates that the principles are what matters.

The basic principles are:

-

Start at a level appropriate to the context.

-

Escalate slowly.

-

Actively de-escalate unless they escalate back.

-

When dealing with a sufficiently clueless dude you can relax this a bit.

-

Don’t escalate if you think either of you would regret it later.

-

Understand when you are entering the ‘warning zone’ where you can no longer fully pretend you maybe aren’t flirting at all, where you thus risk making someone actively uncomfortable or causing an actively negative reaction.

-

Understand when you are entering the ‘danger zone’ where you can get yourself or someone else into real trouble.

-

It is very hard to disguise your level of being sexually pushy, which means that being actually not that pushy is the correct move on all levels.

Some notes on the specific actions:

-

They correctly identify that ‘asking if I can make a flirtatious comment’ is a larger escalation than actually making the flirtatious comment. I think he misidentifies the reasoning here, it’s not that this implies a ‘more flirtatious’ comment, it’s that asking makes your action not ambiguous and is requesting a non-ambiguous escalation.

-

I also think that asking for someone’s number without a plausible other reason (aka ‘closing’) should be much farther down the list than they have it. If the action is clearly in a dating context this is in the warning zone. But with a good enough excuse it isn’t even flirting. High variance.

-

Telling a joke can certainly be flirting but if the joke isn’t risque it’s a free action, fully deniable and ambiguous, you can do this pretty much at any time.

Flirting is pretty awesome. Alas, flirting seems to be getting rare and men are afraid to do it. The perception here has little basis in reality, but fear of tail risk (or in some cases, thinking it’s not even a tail risk) works whether or not the thing you are afraid of is real.

Cartoons Hate Her: But increasingly, I see young men claiming that they’re afraid to flirt with women in social settings, even at bars or parties, because the woman could “ruin their lives.” I saw one insisting that there’s a 50% chance any woman you approach will send you to jail. I think (or at least, I thought) most men know that women won’t really ruin their lives for talking to them at a club.

The worst thing that will happen is rude rejection and ridicule, which sucks for a bunch of other reasons (I’d have a hard time with that if it happened to me!) but isn’t life-ruining. And as any established pickup artist will tell you, the key to success is to lose the fear of rejection, and that happens when you see it all as a low-stakes numbers game.

Obviously she is correct, unless you are doing something very wrong in a way that should be rather obvious, you use a reasonable escalation ladder and you take no for an answer, the chance of a woman you approach trying to ‘run your life’ let alone ‘send you to jail’ is epsilon.

Cartoons Hate Her: The young women today who are upset that men don’t approach them aren’t the same women who decided any approach was harassment in 2015. We don’t all attend an annual bitch conference.

I recall getting yelled at in the Jezebel comments section in like 2014 bc I said it’s not bad for a man to come onto a woman if he respects a “no.” We existed back then and people told us to shut up!

I actually don’t think a fear of women calling the cops is the problem. Making overtures in person (like I wrote here, about dancing) is far more risky re: embarrassment and rejection than simply doing nothing or staying on apps.

I feel like it’s very silly to conflate “I don’t want to be stalked or assaulted” with “men should never flirt with me.” Thinking the latter is silly doesn’t mean you think the former is silly. These should be totally different things.

If all women, or even all liberal women, are to blame for a few overzealous takes in 2013, then by that logic it’s reasonable to treat all men as assaulters because some of them are. Get real.

The problem is, the extreme was loud, and looked to many young men like the norm.

Kat Rosenfeld: hard to overstate how much the culture has been shaped by the fact that circa 2011 sites like Jezebel—and, subsequently, the discourse — were overtaken by millennial women with personality disorders and/or intense grudges over the romantic disappointments they suffered as teens.

Cartoons Hate Her: Drives me nuts when people assume I (or even the majority of women) were complicit in this nonsense. Most people just didn’t want to be assaulted lol. Predictably, the wackos ruined it for everyone.

Caesaraum: what percent of people being wackos ruins the commons for everyone? how much discourse does it take to make the wackos look more prevalent than they are?

Isabel: It is dawning on me just how non-flirtatious our world is. When two people start flirting in front of me in public I feel like I’m witnessing something precious and start rooting for it to go somewhere. It feels so rare now. What happened? We like to talk to each other, remember?

My Fitness Feelings: Women will literally start a global witch hunt against flirting. Successfully destroy it. Forget. Then start a new movement complaining that no one is hitting on them.

Alternatively, the message that went out was ‘do the wrong thing and we will rain hell down upon you’ and even though this was rare even when the man deserved it or worse, and far rarer when they didn’t, there were a few prominent examples of this happening in ambiguous cases, so the combination created a culture of fear. To which some said good and they amplified it.

Then this synthesized into a culture obsessed with smartphones and dating apps, to the point where interactions in physical space seem alien and bizarre, and any kind of flirting or similar behaviors in person seemed verboten.

As always there is an alternate hypothesis, which it seems is both that there is no problem, and that the problem is the fault of the apps or porn:

Dhaaruni: The “men can’t approach women anymore because of man-hating feminists” stuff is very overblown. I’m more of a misandrist than ~99% of women and when I was single, men would approach me, and I was usually amenable to engaging! But, normal human behavior doesn’t drive discourse.

Noah Smith: Yes. To the extent that men don’t approach women anymore, it’s because they’re either on apps, or gooning to porn. The idea that wokeness has turned men into a bunch of timid feminist wimps is just another dumb online panic.

The most obvious place to start is, if she’s talking to you for a remarkably long time, you don’t want to make any assumptions but you (assuming you are interested yourself) do want to at least try flirting a bit and seeing if she’s interested?

Ellie Schnitt: my very sweet friend did not realize that the girl who was talking to him for 2 hours at a party last weekend was interested. I want to reiterate they spoke for 2 entire hours and he didn’t realize she wanted to kiss him until he was told 10 minutes ago.

in his defense a few years ago I talked to a guy I was VERY into for hours just assuming he wasn’t interested. At the end of the night he said “I’m going home, you coming?” and I said “oh is there an after party?” I’ll never forget the look he gave me I think I broke his brain.

NeedMeAJinshi: Holding a conversation for 2 hrs is literally nothing. Not to be that guy, but trying to make “holding a conversation” a sign of interest is exactly how you make every guy think a girl showing him basic respect is her hitting on him.

Eva: protect him at all costs tbh.

Ellie Schnitt: He is the sweetest and deserves the world.

Wayne Reardon: Story of my life. When i was 26 I walked a girl home one night and when we were sitting on the porch out the front of her house I asked her “what are you doing for the rest of the night?”.

She answered “I’ll probably watch a movie. It’s called Who’s Going To Make The First Move”.

I didn’t figure it out until about 2 hours later, so rang her and went back to her house.

Keysmashbandit: Female sexual attraction is a myth. There is no behavior that could possibly communicate it. No matter what, she’s not interested. Don’t bother.

Even if a woman is having sex with you she’s only doing it so she can make fun of you with her friends later. Even if you’re dating. Even if you’re married with children.

Keysmashbandit (replying because it seemed necessary): This post is obvious sarcasm and if you believe it at face value even for a second you need to exit your house immediately and talk to another human face to face.

The concern of NeedMeAJinshi is real, which is why you gracefully check. Talking for two hours at a party goes well beyond basic respect and you should definitely check.

At least be less oblivious than this guy.

Brian: In college I had a female friend who was really cute and I got along with really well. I never asked her out. We were friends! It just never occurred to me.

I drew a daily comic at the time. At some point, I introduced a character, who looked like her, whose name was similar, and who was the main character’s best friend. The running joke was that she had a massive unrequited crush on him but the guy was completely oblivious.

I later found out that she actually had a big crush on me and I was, in fact, completely oblivious. She read my comics and must have thought I was torturing her.

A new paper covers what happened when Tinder first arrived, note that this was largely a replacement of other dating apps.

Online dating apps have transformed the dating market, yet their broader effects remain unclear.

We study Tinder’s impact on college students using its initial marketing focus on Greek organizations for identification. We show that the full-scale launch of Tinder led to a sharp, persistent increase in sexual activity, but with little corresponding impact on the formation of long-term relationships or relationship quality. Dating outcome inequality, especially among men, rose, alongside rates of sexual assault and STDs.

However, despite these changes, Tinder’s introduction did not worsen students’ mental health, on average, and may have even led to improvements for female students.

The full paper is gated, and one must note the unavoidable limitations here. Greek organizations are importantly different from others, and the real difference is that the early dynamics are not going to hold stable over time, and with this kind of study you are not going to see longer term effects.

In terms of ‘mental health,’ the short term effects are reported (presumably self-reported) to be neutral-to-good in aggregate, and the net relationship impacts tiny. Given the other impacts I would presume that the longer term mental health impacts are negative, and for college students to be a group where the net effects are relatively positive.

Periodically we see a version of this claim:

Medjedowo: dating apps, by nature, can’t be ‘too effective’ at matching users, otherwise they’d run out of customers and traffic volume.

Not to be too conspiratorial but how are they incentivizing long term usage, exactly? like the users meet irl but they stacked the deck to sabotage it behind the scenes? as with news media reporting slop my inclination is to ultimately blame the consumers– if they could sell.

I mean, yes, in theory at some point this becomes true. At any reasonable margin this simply isn’t true, certainly not for anyone outside of Match group. The reputational effects swamp everything else, especially since even if you are 100% to get a successful match most relationships don’t last. You’ll be back, and if you aren’t you’ll be telling all your friends how you met.

You do want to somewhat sabotage the lives of free users to force them to pay,and thus you gate useful things behind paywalls, but that’s true of essentially all free apps everywhere to some degree.

Having nerdy interests is only a minor handicap, if you (1) own it with no stress and (2) don’t require or impose them on your partners or let them get in the way. Chances are high your actual problem to fix lies elsewhere.

If someone actually vetoes you because of your hobby even if you own it with no stress and no imposition of it on others, it wasn’t a good match anyway. That’s positive selection right there. The same goes for political vetoes.

This conversation started off with the (decent looking) Guy Who Swiped Right Two Million Times and got one date. Ten out of ten points for persistence and minus several million for repeating the same action expecting different results and also minus another million for having actual zero swiping standards.

He’s plausibly got requirement one nailed but number two might be a problem.

The problem clearly ran deep. It’s one thing to do 2.05 million swipes and get only 2,053 matches. That’s 1 in 1,000, which to be fair is very bad, and it’s not hard to generate theories as to how that happened. But then he had 1,269 chats and that led to 1 date, and at that point dude it’s something else entirely.

Max: I think he’s just scary.

The contradictions are there right off the bat. He does have standards, in his way.

Goblin: i think ultimately this is a branding issue tbh

Fish photos signal “conservative normie,” owning 33 snakes signals “weirdo leftie.”

Basically no one making it through his photo filter survives his special interest filter.

I don’t think that’s weirdo lefty, you can totally have 33 snakes and be a weirdo rightie. Claude suspects ‘trying too hard to be quirky,’ which definitely fits.

Sardine Thief: I think he’s just weird and antisocial and from what I’ve seen floating around of the rest of his profile acts vaguely menacing and domineering, u can literally have whatever weird interest you want and the right girl will find it charming if you’re not otherwise a weirdo

i used to think i was basically this guy and was doomed bc of my “weird” interests in like historical asian linguistics and comparative religion and when i reframed it as a “me” problem instead of a “my interests” problem i met a woman who actually likes me like a month later

Goblin: oh wow wait what what can you elaborate this is a really good case study

Sardine Thief: i had the typical nerdy guy problem of thinking it was my nerdy interests that made women not interested and not that very same self-pitying attitude

i don’t think that’s specifically this guy’s problem but “my interests are unlovable” is often a smokescreen to protect the ego from having to address what the real problem is, because saying “i need to work on how i relate to and communicate with women” and then doing it is a lot harder than saying “they don’t like me cuz they hate my snakes”

my problem was actual gynophobia, i spent most of my life til ~19 being emotionally/verbally abused by female caregivers & had to work out some things to be able to not treat women like “landmine that needs to be placated with chores and fawning to maybe not blow up in my face”

Goblin: oh whoa yeah that makes a lot of sense! good on ya for working it out! this feels like a v common path but people end up getting stuck at the “nobody likes my weird interests” point

Sardine Thief: yeah, it does loop back around to branding, but reinventing your branding on more than a surface level requires deeply examining the pillars that the way you present yourself are built on to begin with

Goblin: Yeaaah!

At most, you get one move at this level. You definitely don’t get two.

The broader point is mostly right, the narrow point seems obviously wrong?

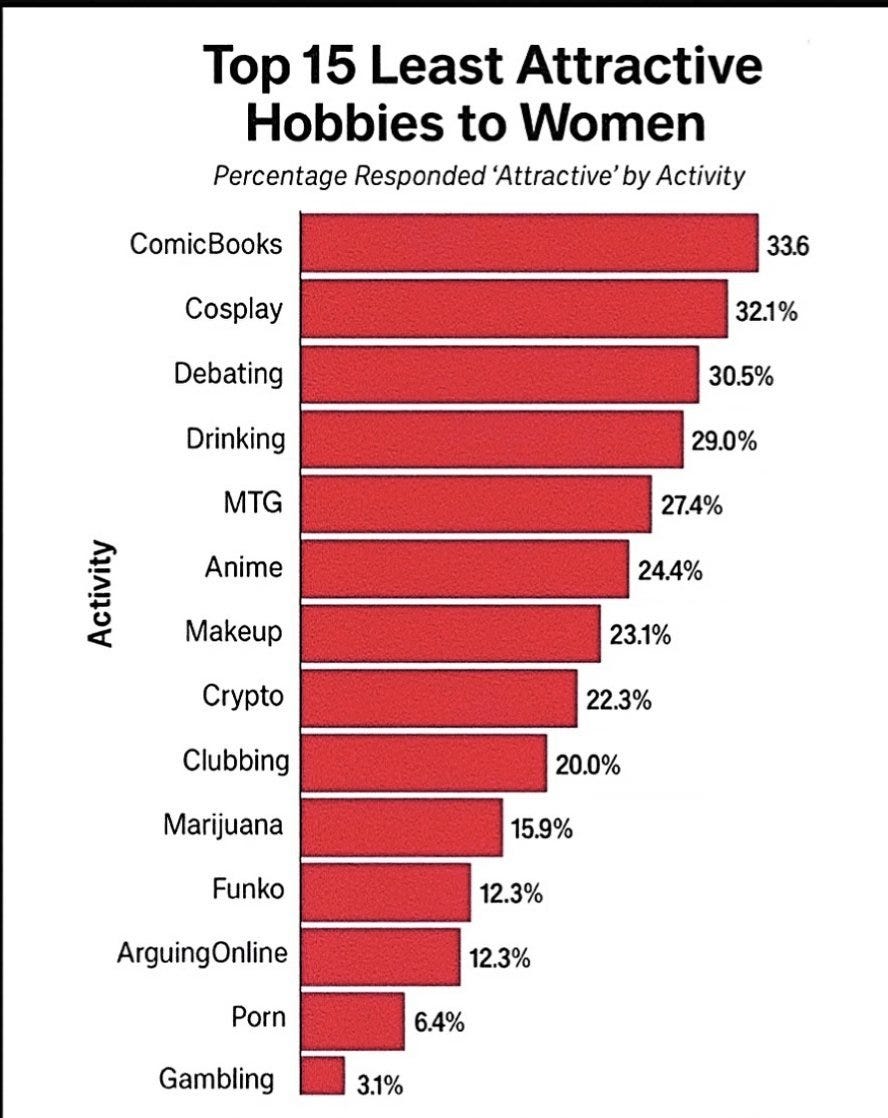

Jakeup: If fewer than one third of men are into comic books (likely) or cosplay (almost certainly), then getting into comic books or cosplay increases your market attractiveness.

The broader point isn’t just that many “unattractive” traits are undersupplied and thus are actually good, but that being *anything at allis attractive the only thing oversupplied in the dating market are people who are nothing in particular and do little much of anything.

In general, yes, better to be into as many non-harmful things as you can, so long as you are capable of shutting up about them and not letting them interfere with your dating activities. The reason so many of the things here are unattractive is that they do actively interfere, either because people can’t stop talking about them, they are money sinks, they have very bad correlations, or they do active harm to you, or a combination thereof.

You definitely can’t say that if X% of women find [Y] attractive, then at least X% of men should have attribute [Y], or vice versa, or that this indicates undersupply if not true, or anything like it. That’s not how it works for various obvious reasons.

But yes, if you are not into some things, you need to pick at least one something and get into it, ideally something that people you are interested in will find interesting.

Why is (illusionary) magic considered lame and low status? I am with Chana Messinger here that if executed and presented well, magic gives you charm and charisma, and seems great at ice breaking and demonstrating skill and value, and is actually great.

I also think Jack is correct that most people who use magic in this way are bad at it, and that bad magic is indeed lame and low status. Most magicians are not successful, and most people presenting magic are showing that they’ve overinvested in magic relative to other things. So is being ‘too in’ in magic as a strategy relative to your level of magic success.

There is especially a problem if you are obviously doing the magic as a strategy to get girls, doubly so if you are shoehorning your magic into an interaction where it shouldn’t be, or if you present as if you think you’re super hot stuff when you clearly aren’t. Having magic available as a tool is awesome, if you have some skill, but part of making the magic happen is knowing when not to make the magic happen.

The other problem is that illusionary magic (unlike magick or Magic: The Gathering) is at its core illusion and deception. Do you want to make that your brand? What other kinds of scams are you trying to pull?

It’s easy to get caught up in ‘how to play correctly’ and the fact that you can indeed succeed on the apps with effort, and forget that even in the best case all that rejection is going to feel really terrible if you let it.

veloread: Honestly, I had to quit Bumble for years because of what it did to me. More than any other dating app, on Bumble I have had an awful time.

My experience was – and to a lesser extent, remains, now that I’m on it again – this:

Set filters to the people I’m interested in. See profile after profile of fascinating, funny, intelligent-seeming people who are my type. Think to myself about whether we’d be compatible. Swipe, in the absolute and extreme confidence that I won’t get a match. Don’t get any matches.

That constant rejection – person after person after person – and the few times you match, and you find the other person just doesn’t put in any effort at all, because, well, the gender ratio and dynamics on these apps is awful, and so she’s got a huge pile of matches and messages to deal with.

The experience made me angry, and it made me sad. I went on these apps after a breakup, hoping that I’d be able to “put myself out there”, but it ended up making the pain of that loss much worse. I had thought, because of who I had been with – and because our relationship ended not because of anything either of us did, but because we were at different stages of our lives – that I was handsome and funny and desirable. That I’d come off as someone people would like to talk to, laugh with, have adventures with.

Signull: people ask how i stay attuned to what tech actually does… the emotions it triggers, the ways it shapes lives, the subtle effects or unexpected magici it delivers. the answer’s simple. i read. not whitepapers. not founder threads. this. stuff like this.

posts like this are where the truth lives. visceral, unpolished, & real. someone trying to make sense of their own pain through a product that promised connection but delivered emptiness. this is user research. this is culture listening.

the internet gives you a front row seat to the human condition. you just have to care enough to look.

Rany Treibel: I love these kind of posts because they’re vulnerable in a productive way, not attention seeking, not acting like a victim, just sharing an experience. Could this person do things better? sure, but that doesn’t matter here. Even those of us who have no trouble on dating sites still experience this for weeks on end sometimes.

Robin Hanson: I gotta say this wouldn’t have done much for my mental health either. Pretty dystopian hell scenario.

The obvious mental trick, far easier said than done, is to not see this as rejection.

As in, you’re not being rejected so much as not being considered. You’re not making a request so much as you’re confirming you would be open to something happening.

The algorithm is gating your success behind a bunch of grinding, until someone takes the time to consider you enough to have meaningfully rejected you rather than a photo, to have chosen to reject rather than not have had time to choose at all. And it is only once someone engages you in conversation for real that you’ve actually been rejected as a person.

Until then, yes you should be aware of your metrics versus others so you can work on improving, but in a real way this ‘doesn’t count.’

Would this feature work?

Andrew Rettek: Idea for a dating site feature. Every time you swipe on someone you need to write a little bit about why before you can swipe again/message that match. That feedback is collected for every user and every user can request an LLM summary of it (but not the actual text).

This adds friction to slow down mindless swiping, gives users (successful and unsuccessful) feedback if they want it, and forces people to think at all about what they’re looking for in a match. I don’t thing this solves “the apps” but it probably helps a bit.

The obvious problem with this is that users don’t want to do this. The point of swiping is that it is almost instant, it requires no thought, no words, like a slot machine. That wins in the marketplace because that’s what women choose.

So most users, most importantly most women, will quickly start to use the cut and paste, or something damn close to it. I mean, if you’re swiping on a profile, is there really that much to say there, and if they aren’t even going to read it before deciding why should you spend the effort? ‘Not hot’? In general, you can’t have mechanisms at odds with the user like this.

The variant of this that has non-zero chance of working is that the man would swipe and write a message first, and only then does the woman get to swipe, and perhaps you would have an AI that would give it a uniqueness score relative to other messages the same person sent, or you would otherwise engage in an auto-filter on the message along with everything else that is available for an LLM to filter profiles.

The first major dating site to get AI and usefully costly signaling properly into the early matching process, in a way that actually fixed the incentives without wrecking the experience, is going to see some big returns. It’s odd how little they seem to be focusing on this problem.

Alternatively, what about matching people by browser history? If there is a way to avoid data security and privacy concerns (ha!) then there are actually a lot of advantages. This should match people by various forms of common interests and content consumption patterns.

It also serves as a way to effectively say things you couldn’t otherwise say. As in, suppose you have a very niche interest, perhaps a kink and perhaps something else. You wouldn’t want to put that information in a profile, but this can potentially work around that.

That suggests a different design, which is AI-only honest-request blind matching.

As in, you write down what you really, truly want and care about. All the really good stuff. A document you would absolutely not want anyone else to read, including both freeform statements and answers to a range of questions.

Then, an AI looks at this, and compares your requests and statements to those of others, and gives compatibility scores, in a way that is protected against hacking the system in various ways (e.g. you don’t want someone to be able to add and remove ‘I’m extremely into [X]’ from their profile and compare all the scores, thus revealing who is exactly how into or not into [X].)

You could also offer this evaluation as a one-time service, where a fully anonymized server can take any given two write-ups [X], [Y] from different sources, and then evaluate.

Also note this does not have to be romantic. You can also do this, at scale or one-on-one, for finding ordinary friends or anything else.

Aella: Finally got on Tea. I don’t think most of you guys have to worry

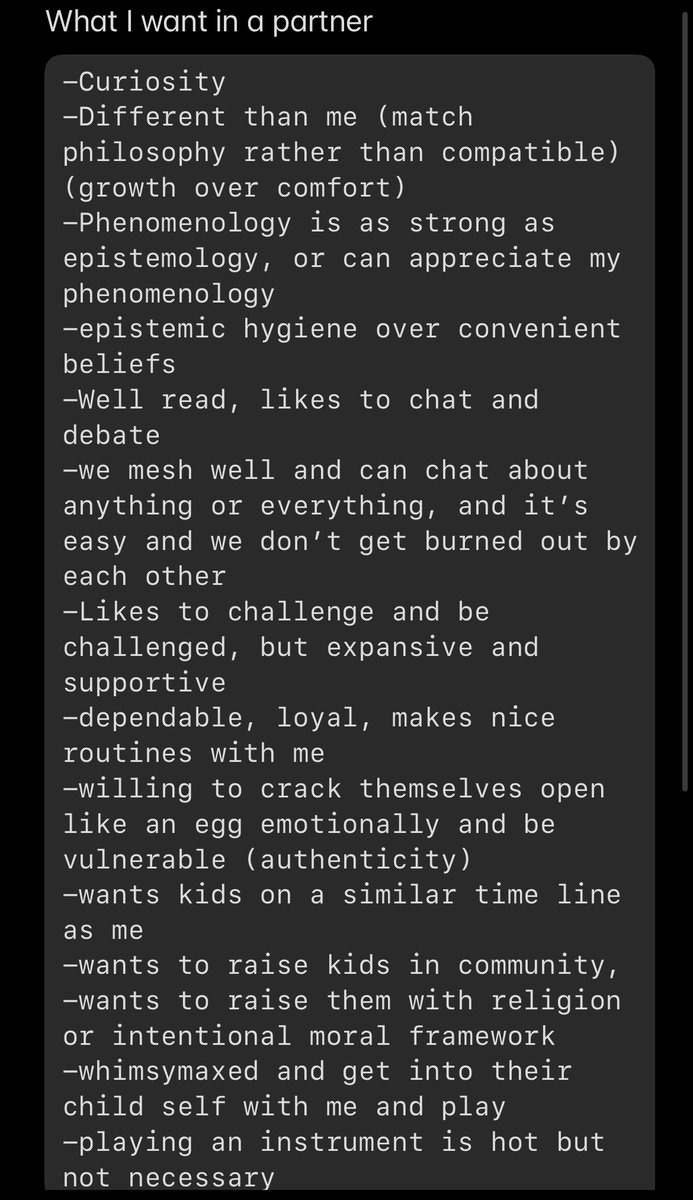

I continue to think having a Date Me Doc, which is literally a document that lays out at length who you are, what you bring to the table and what you’re looking for at length, is an excellent move.

Here’s a resource that seems worth getting in on, if you’re in the area and the right Type of Guy sufficiently to qualify. This seems like The Way, it only works if you don’t know what she’s writing down:

Brooke Bowman: The girlies would like to browse the database.

Social Soldier: hey guys, if you want to go in the bachelor’s database lmk. If I know you, I will screen you and put you in for the girlies to see. Sorry, no, you won’t get to know what I say.

If you know of any bachelors this is what I’m looking for I like em intense.

Cate Hall: I can’t get Nan to do a date-me so fellas take note that she is SINGLE, WARM, FEROCIOUS, HOT AS HELL, and INTO NERDS.

Nan Ransohoff (website): well I asked claude what historical figures he’d set me up with and I.. have never felt so seen?

anyway, I’ll be hosting a feynman lookalike party later this year ✌🏼

It seems likely matchmaking is underrated, at least relative to dating apps and for those who can afford the fees? Or it would be, if the services deliver the goods.

I’ve now seen several ads on the subway recently for matchmaking services. The latest was for a service called Tawkify, which claims to be rather large, and I figured I’d do some brief investigation.

Clients pay for a package of curated dates managed by a dedicated matchmaker, based on your criteria, or you can pay a much smaller amount ($100/year) to be the candidate pool. They will also recruit outside the platform.

Yes, the price of ~$4500 for three matches is not cheap (bigger packages seem cheaper per date), but compare it to the number of hours you would otherwise spend to get to that point, and the quality of the matches you get from the apps, and ask if you were enjoying those hours of app work.

The problem with the matchmaking option is what you would expect it to be. The service is reportedly using predatory sales tactics and does not actually make much of an attempt to Do The Thing.

Yes, you would expect a lot of unhappy complaining customers no matter how good the service was but even by that standard this look is terrible and there are a lot of signs of reputation manipulation.

Google Deep Research: A stark contradiction exists between the company’s heavily promoted high rating on Trustpilot and the extensive volume of severe complaints lodged with the Better Business Bureau (BBB) and on public forums like Reddit. A pattern of recurring complaints alleges misleading sales tactics, poor match quality that disregards client-stated preferences, high matchmaker turnover, and the enforcement of rigid, non-refundable contracts that place the full financial burden on the consumer.

…

One detailed complaint from a client who paid $4,500 articulated the perceived unfairness of being matched with men who had only paid the $99 database fee, a critical detail she claims was never disclosed during the sales process.

…

Step 1: Initial Screening & Sales Call. The process begins when a prospective client completes an online application, which vets for basic criteria such as age, location, and income. If the applicant is deemed a potential fit, they are scheduled for a call with a “client experience specialist” or salesperson. This initial call is a critical juncture and a source of numerous consumer complaints.

Multiple reports filed with the BBB and on public forums describe this as a high-pressure sales call where key, and often deal-breaking, details of the service—such as the mandatory blind date format or the strict non-refundable policy—are allegedly omitted, downplayed, or obscured. Some prospective customers have reported being chastised or emotionally manipulated when they balked at the high price point.

…

When a matchmaker does make contact, the screening process is explicitly one-way. The interview and vetting are conducted to determine the individual’s suitability for a specific paying Client. The Member’s or Recruit’s preferences are secondary; the primary objective is to find someone who meets the Client’s criteria.

So the trick is to find the good version of the service.

Also, it seems there is now at least one person running a non-monogamous matchmaking service focusing on Austin, Oakland and Boulder.