This week, Philip Trammell and Dwarkesh Patel wrote Capital in the 22nd Century.

One of my goals for Q1 2026 is to write unified explainer posts for all the standard economic debates around potential AI futures in a systematic fashion. These debates tend to repeatedly cover the same points, and those making economic arguments continuously assume you must be misunderstanding elementary economic principles, or failing to apply them for no good reason. Key assumptions are often unstated and even unrealized, and also false or even absurd. Reference posts are needed.

That will take longer, so instead this post covers the specific discussions and questions around the post by Trammell and Patel. My goal is to both meet that post on its own terms, and also point out the central ways its own terms are absurd, and the often implicit assumptions they make that are unlikely to hold.

They affirm, as do I, that Piketty was centrally wrong about capital accumulation in the past, for many well understood reasons, many of which they lay out.

They then posit that Piketty could have been unintentionally describing our AI future.

As in, IF, as they say they expect is likely:

-

AI is used to ‘lock in a more stable world’ where wealth is passed to descendants.

-

There are high returns on capital, with de facto increasing returns to scale due to superior availability of investment opportunities.

-

AI and robots become true substitutes for all labor.

-

(Implicit) This universe continues to support humanity and allows us to thrive.

-

(Implicit) The humans continue to be the primary holders of capital.

-

(Implicit) The humans are able to control their decisions and make essentially rational investment decisions in a world in which their minds are overmatched.

-

We indefinitely do not do a lot of progressive redistribution.

-

(Implicit) Private property claims are indefinitely respected at unlimited scale.

THEN:

-

Inequality grows without bound, the Gini coefficient approaches 1.

-

Those who invest wisely, with eyes towards maximizing long term returns, end up with increasingly large shares of wealth.

-

As in, they end up owning galaxies.

Patel and Trammell: But once robots and computers are capable enough that labor is no longer a bottleneck, we will be in the second scenario. The robots will stay useful even as they multiply, and the share of total income paid to robot-owners will rise to 1. (This would be the “Jevons paradox”.)

Later on, to make the discussions make sense, we need to add:

-

There is a functioning human government that can impose taxes, including on capital, in ways that end up actually getting paid.

-

(Unclear) This government involves some form of Democratic control?

If you include the implicit assumptions?

Then yes. Very, very obviously yes. This is basic math.

In this scenario, sufficiently capable AIs and robots are multiplying without limit and are perfect substitutes for human labor.

Perhaps ‘what about the distribution of wealth among humans’ is the wrong question?

I notice I have much more important questions about such worlds where the share of profits that goes to some combination AI, robots and capital rises to all of it.

Why should the implicit assumptions hold? Why should we presume humans retain primary or all ownership of capital over time? Why should we assume humans are able to retain control over this future and make meaningful decisions? Why should we assume the humans remain able to even physically survive let alone thrive?

Note especially the assumption that AIs don’t end up with substantial private property. The best returns on capital in such worlds would obviously go to ‘the AIs that are, directly or indirectly, instructed to do that.’ So if AI is allowed to own capital, the AIs end up with control over all the capital, and the robots, and everything else. It’s funny to me that they consider charitable trusts as a potential growing source of capital, but not the AIs.

Even if we assumed all of that, why should we assume that private property rights would be indefinitely respected at limitless scale, on the level of owning galaxies? Why should we even expect property rights to be long term respected under normal conditions, here on Earth? Especially in a post calling for aggressive taxation on wealth, which is kind of the central ‘nice’ case of not respecting private property.

Expecting current private property rights to indefinitely survive into the transformational superintelligence age seems, frankly, rather unwise?

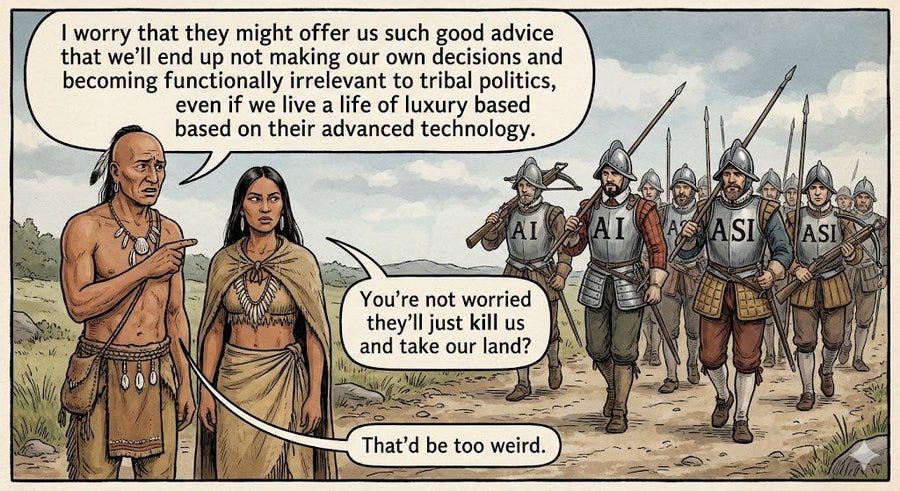

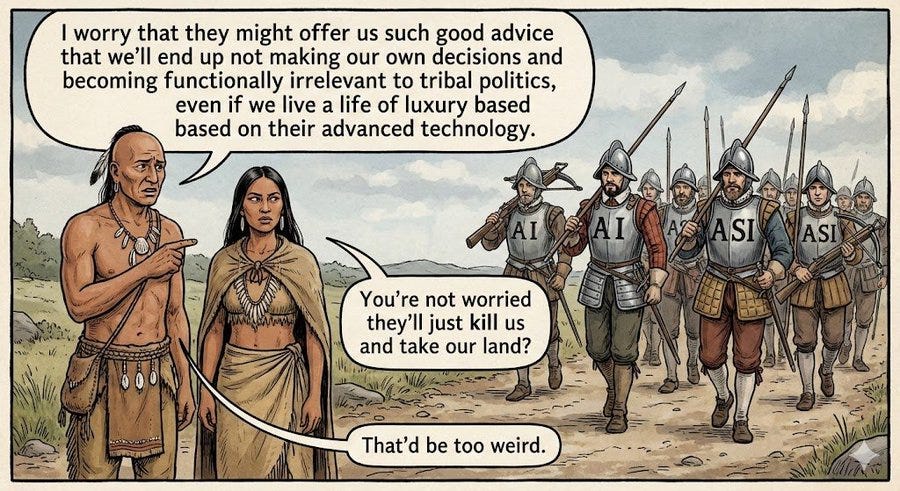

Eliezer Yudkowsky: What is with this huge, bizarre, and unflagged presumption that property rights, as assigned by human legal systems, are inviolable laws of physics? That ASIs remotely care? You might as well write “I OWN YOU” on an index card in crayon, and wave it at the sea.

Oliver Habryka: I really don’t get where this presumption that property ownership is a robust category against changes of this magnitude. It certainly hasn’t been historically!

Jan Kulveit: Cope level 1: My labour will always be valuable!

Cope level 2: That’s naive. My AGI companies stock will always be valuable, may be worth galaxies! We may need to solve some hard problems with inequality between humans, but private property will always be sacred and human.

Then, if property rights do hold, did we give AIs property rights, as Guive Assadi suggests (and as others have suggested) we should do to give them a ‘stake in the legal system’ or simply for functional purposes? If not, that makes it very difficult for AIs to operate and transact, or for our system of property rights to remain functional. If we do, then the AIs end up with all the capital, even if human property rights remain respected. It also seems right to at some point, if the humans are not losing their wealth fast enough, to expect AIs coordinating to expropriate human property rights while respecting AI property rights, as has happened commonly throughout the history of property rights when otherwise disempowered groups had a large percentage of wealth.

The hidden ‘libertarian human essentialist’ assumptions continue. For example, who are these ‘descendants’ and what are the ‘inheritances’? In these worlds one would expect aging and disease to be solved problems for both humans and AIs.

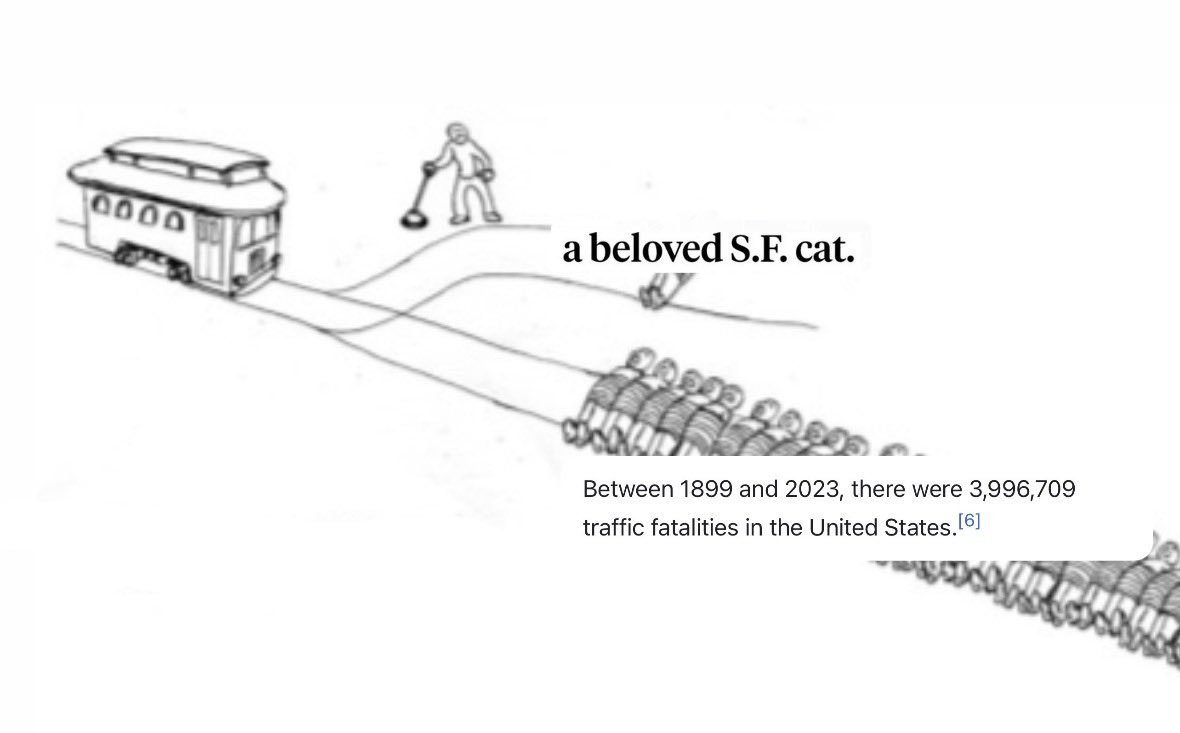

Such talk and economic analysis often sounds remarkably parallel to this:

The world described here has AIs that are no longer normal technology (while it tries to treat them as normal in other places anyway), it is not remotely at equilibrium, there is no reason to expect its property rights to endorse or to stay meaningful, it would be dominated by its AIs, and it would not long endure.

If humans really are no longer useful, that breaks most of the assumptions and models of traditional econ along with everyone else’s models, and people typically keep assuming actually humans will still be useful for something sufficiently for comparative advantage to rescue us, and can’t actually wrap their heads around it not being true and humans being true zero marginal product workers given costs.

Paul Crowley: A lot of these stories from economics about how people will continue to be valuable make assumptions that don’t apply. If the models can do everything I do, and do it better, and faster, and for less than it costs me to eat, why would someone employ me?

It’s really hard for people to take in the idea of an AI that’s better than any human at *everytask. Many just jump to some idea of an uber-task that they implicitly assume humans are better at. Satya Nadella made exactly this mistake on Dwarkesh.

Dwarkesh Patel: If labor is the bottleneck to all the capital growth. I don’t see why sports and restaurants would bottleneck the Dyson sphere though.

That’s the thing. If we’re talking about a Dyson sphere world, why are we pretending any of these questions are remotely important or ultimately matter? At some point you have to stop playing with toys.

A lot of this makes more sense if we don’t think it involves Dyson spheres.

Under a long enough time horizon, I do think we can know roughly what the technologies will look like barring the unexpected discovery of new physics, so I’m with Robin Hanson here rather than Andrew Cote, today is not like 1850:

Andrew Cote: This kind of reasoning – that the future of humanity will be rockets, robots, and dyson swarms indefinitely into the future, assumes an epistemological completeness that we already know the future trade-space of all possible technologies.

It is as wrong as it would be to say, in 1850, that in two hundred years any nation that does not have massive coal reserves will be unfathomably impoverished. What could there be besides coal, steel, rail, and steam engines?

Physics is far from complete, we are barely at the beginning of what technology can be, and the most valuable things that can be done in physical reality can only be done by conscious observers, and this gets to the very heart of interpretations of quantum mechanics and physical theory itself.

Robin Hanson: No, more likely than not, we are constrained to a 3space-1time space-time where the speed of light is a hard limit on travel/influence, thermodynamics constrains the work we can do, & we roughly know what are the main sources of neg-entropy. We know a lot more than in 1850.

Even in the places were the assumptions aren’t obviously false, or you want to think they’re not obviously false, and also you want to assume various miracles occur such that we dodge outright ruin, certainly there’s no reason to think the future situation will be sufficiently analogous to make these analyses actually make sense?

Daniel Eth: This feels overly confident for advising a world completely transformed. I have no idea if post-AGI we’d be better off taxing wealth vs consumption vs something else. Sure, you can make the Econ 101 argument for taxing consumption, but will the relevant assumptions hold? Who knows.

Seb Krier: I also don’t have particularly good intuitions about what a world with ASI, nanotechnology and Dyson swarms looks like either.

Futurist post-AGI discussions often revolve around thinking at the edge of what’s in principle plausible/likely and extrapolating more and more. This is useful, but the compounding assumptions necessary to support a particular take contain so many moving parts that can individually materially affect a prediction.

It’s good to then unpack and question these, and this creates all sorts of interesting discussions. But what’s often lost in discussions is the uncertainty and fragility of the scaffolding that supports a particular prediction. Some variant of the conjunction fallacy.

Which is why even though I find long term predictions interesting and useful to expand the option space, I rarely find them particularly informative or sufficient to act on decisively now. In practice I feel like we’re basically hill-climbing on a fitness landscape we cannot fully see.

Brian Albrecht: I appreciate Dwarkesh and Philip’s piece. I responded to one tiny part.

But I’ll admit I don’t have a good intuition for what will happen in 1000 years across galaxies. So I think building from the basics seems reasonable.

I don’t even know that ‘wealth’ and ‘consumption’ would be meaningful concepts that look similar to how they look now, among other even bigger questions. I don’t expect ‘the basics’ to hold and I think we have good reasons to expect many of them not to.

Ben Thompson: This world also sounds implausible. It seems odd that AI would acquire such fantastic capabilities and yet still be controlled by humans and governed by property laws as commonly understood in 2025. I find the AI doomsday scenario — where this uber-capable AI is no longer controllable by humans — to be more realistic; on the flipside, if we start moving down this path of abundance, I would expect our collective understanding of property rights to shift considerably.

Ultimately all of this, as Tomas Bjartur puts it, imagines an absurd world, assuming away all of the dynamics that matter most. Which still leaves something fun and potentially insightful to argue about, I’m happy to do that, but don’t lose sight of it not being a plausible future world, and taking as a given that all our ‘real’ problems mysteriously turn out fine despite us having no way to even plausibly describe what that would look like, let alone any idea how to chart a path towards making it happen.

Thus from this point on, this post accepts the premises listed above, ad argumento.

I don’t think that world actually makes a lot of sense on reflection, as an actual world. Even if all associated technical and technological problems are solved, including but not limited to all senses of AI alignment, I do not see a path arriving at this outcome.

I also have lots of problems with parts the economic baseline case under this scenario.

The discussion is still worth having, but one needs to understand all this up front.

It’s even worth having that discussion even if the economists are mostly rather dense and smg and trotting out their standard toolbox as if nothing else ever applies to anything. I agree with Yo Shavit that it is good that this and other writing and talks from Dwarkesh Patel are generating serious economic engagement at all.

If meaningful democratic human control over capital persisted in a world trending towards extreme levels of inequality, I would expect to see massive wealth redistribution, including taxes on or confiscation of extreme concentrations of wealth.

If meaningful democratic control didn’t persist, then I would expect the future to be determined by whatever forces had assumed de facto control. By default I would presume this would be ‘the AIs,’ but the same applies if some limited human group managed to retain control, including over the AIs, despite superintelligence. Then it would be up to that limited group what happened after that. My expectation would be that most such groups would do some redistribution, but not attempt to prevent the Gini coefficient going to ~1, and they would want to retain control.

Jan Kelveit’s pushback here seems good. In this scenario, human share of capital will go to zero, our share of useful capability for violence will also go to zero, the use of threats as leverage won’t work and will go to zero, and our control over the state will follow. Harvey Lederman also points out related key flaws.

As Nikola Jurkovic notes, if superintelligence shows up and if we presume we get to a future with tons of capital and real wealth but human labor loses market value, and if humans are still alive and in control over what to do with the atoms (big ifs), then as he points out we fundamentally are going to either do charity for those who don’t have capital, or those people perish.

That charity can take the form of government redistribution, and one hopes that we do some amount of this, but once those people have no leverage it is charity. It could also take the form of private charity, as ‘the bill’ here will not be so large compared to total wealth.

It is not obvious that we would.

Inequality of wealth is not inherently a problem. Why should we care that one man has a million dollars and a nice apartment, while another has the Andromeda galaxy?What exactly are you going to do with the Andromeda galaxy?

A metastudy in Nature released last week concluded that economic inequality does not equate to poor well-being or mental health.

I also agree with Paul Novosad that it seems like our appetite for a circle of concern and generous welfare state is going down, not up. I’d like to hope that this is mostly about people feeling they themselves don’t have enough, and this would reverse if we had true abundance, but I’d predict only up to a point, no we’re not going to demand something resembling equality and I don’t think anyone needs a story to justify it.

Dwarkesh’s addendum that people are misunderstanding him, and emphasizing the inequality is inherently the problem, makes me even more confused. It seems like, yes, he is saying that wealth levels get locked in by early investment choices, and then that it is ‘hard to justify’ high levels of ‘inequality’ and that even if you can make 10 million a year in real income in the post-abundance future Larry Page’s heirs owning galaxies is not okay.

I say, actually, yes that’s perfectly okay, provided there is stable political economy and we’ve solved the other concerns so you can enjoy that 10 million a year in peace. The idea that there is a basic unit, physical human minds, that all have rights to roughly equal wealth, whereas the more capable AI minds and other entities don’t, and anything else is unacceptable? That doesn’t actually make a lot of sense, even if you accept the entire premise.

Tom Holden’s pushback is that we only care about consumption inequality, not wealth inequality, and when capital is the only input taking capital hurts investment, so what you really want is a consumption tax.

Similar thinking causes Brian Albrecht to say ‘redistribution doesn’t help’ when the thing that’s trying to be ‘helped’ is inequality. Of course redistribution can ‘help’ with that. Whereas I think Brian is presuming what you actually care about is the absolute wealth or consumption level of the workers, which of course can also be ‘helped’ by transfers, so I notice I’m still confused.

But either way, no, that’s not what anyone is asking in this scenario – the pie doth overfloweth, so it’s very easy for a very small tax to create quite a lot of consumption, if you can actually stay in control and enforce that tax.

I agree that in ‘normal’ situations among humans consumption inequality is what matters, and I would go further and say absolute consumption levels are what matters most. You don’t have to care so much about how much others consume so long as you have plenty, although I agree that people often do. I have 1000x what I have now and I don’t age or die, and my loved ones don’t age or die, but other people own galaxies? Sign me the hell up. Do happy dance.

Dwarkesh explicitly disagrees and many humans have made it clear they disagree.

Framing this as ‘consumption’ drags in a lot of assumptions that will break in such worlds even if they are otherwise absurdly normal. We need to question this idea that meaningful use of wealth involves ‘consumption,’ whereas many forms of investment or other such spending are in this sense de facto consumption. Also AIs don’t ‘consume’ is this sense so again this type of strategy only accelerates disempowerment.

The good counter argument is that sufficient wealth soon becomes power.

Paul Graham: The rational fear of those who dislike economic inequality is that the rich will convert their economic power into political power: that they’ll tilt elections, or pay bribes for pardons, or buy up the news media to promote their views.

I used to be able to claim that tech billionaires didn’t actually do this — that they just wanted to refine their gadgets. But unfortunately in the current administration we’ve seen all three.

It’s still rare for tech billionaires to do this. Most do just want to refine their gadgets. That habit is what made them billionaires. But unfortunately I can no longer say that they all do.

I don’t think the inequality being ‘hard to justify’ is important. I do think ‘humans, often correctly, beware inequality because it leads to power’ is important.

Garry Tan’s pushback of ‘whoa Dwarkesh, open markets are way better than redistribution’ and all the standard anti-redistribution rhetoric and faith that competition means everyone wins, a pure blind faith in markets to deliver all of us from everything and the only thing we have to fear is government regulations and taxes and redistribution, attacking Dwarkesh for daring to suggest redistribution could ever help with anything, is a maximally terrible response.

Not only is it suicidal in the face of the problems Dwarkesh is ignoring, it is also very literally suicidal in the face of labor income dropping to zero. Yes, prices fall and quality rises, and then anyone without enough capital starves anyway. Free markets don’t automagically solve everything. Mostly free markets are mostly the best solutions to most problems. There’s a difference.

You can decide that ‘inequality’ is not in and of itself a problem. You do still need to do some amount of ‘non-market’ redistribution if you want humans whose labor is not valuable to survive other than off capital, because otherwise they won’t. Maybe Garry Tan is fine with that if it boosts the growth rate. I’m not fine with it. The good news is that in this scenario we will be supremely wealthy, so a very small tax regime will enable all existing humans to live indefinitely in material wealth we cannot dream of.

Okay, suppose we do want to address the ‘inequality’ problem. What are our options?

Their first proposed solution are large inheritance taxes. As noted above, I would not expect these ultra wealthy people or AIs to die, so I don’t expect there to be inheritances to tax. If we lean harder into ‘premise!’ and ignore that issue, then I agree that applying taxes on death rather than continuously has some incentive advantages but also it introduces an insane level of distorted incentives if you tried to make this revenue source actually matter versus straight wealth taxes.

The proposed secondary solution of a straight up large wealth tax is justified by ‘the robots will work just as hard no matter the tax rate,’ to argue that this won’t do too much economic damage, but to the extent they are minds or minds are choosing the robot behaviors this simply is not effectively true, as most economists will tell you. They might work as hard, but they won’t work in the same ways towards the same ends, because either humans or AIs will be directing what the robots do and the optimization targets have changed. Communist utopia is still communist utopia, it’s weird to see it snuck in here as if it isn’t what it is.

The tertiary solution, a minimum ‘spending’ requirement, starts to get weird quickly if you try to pin it down. What is spending? What is consumption? This would presumably be massively destructive, causing massive wasteful consumption, on the level of ‘destroying a large portion of the available mass-energy in the lightcone for no effect.’ It’s a cool new thing to think about. Ultimately I don’t think it works, due to mismatched conceptual assumptions.

They also suggest taxing ‘natural resources.’ In a galactic scenario this seems like an incoherent proposal when applied to very large concentrations of wealth, not functionally different than straight up taxing wealth. If it is confined to Earth, then you can get some mileage out of this, but that’s solving your efficient government revenue problems, not your inequality problems. Do totally do it anyway.

The real barriers to implementing massive redistribution are ‘can the sources of power choose to do that?’ and ‘are we willing to take the massive associated hits to growth?’

The good news for the communist utopia solution (aka the wealth tax) is that it would be quite doable to implement it on a planetary scale, or in ‘AI as normal technology’ near term worlds, if the main sources of power wanted to do that. Capital controls are a thing, as is imposing your will on less powerful jurisdictions. ‘Capital’ is not magic.

The problem on a planetary scale is that the main sources of real power are unlikely to be the democratic electorate, once that electorate no longer is a source of either economic or military power. If the major world powers (or unified world government) want something, and remain the major world powers, they get it.

When you’re going into the far future and talking about owning galaxies, you then have some rather large ‘laws of physics’ problems with enforcement? How are you going to collect or enforce a tax on a galaxy? What would it even mean to tax it? In what sense do they ‘own’ the galaxy?

A universe with only speed-of-light travel, where meaningful transfers require massive expenditures of energy, and essentially solved technological possibilities, functions very, very differently in many ways. I don’t think they’re being thought through. If you’re living in a science fiction story for real, best believe in them.

As Tyler Cowen noted in his response to Dwarkesh, there are those who want to implement wealth taxes a lot sooner than when AI sends human labor income to zero.

As in, they want to implement it now, including now in California, where there is a serious proposal for a wealth tax, including on unrealized capital gains, including illiquid ones in startups as assessed by the state.

That would be supremely, totally, grade-A stupid and destructive if implemented, on the level of ‘no actually this would destroy San Francisco as the tech capital.’

Tech and venture capital like to talk the big cheap talk about how every little slight is going to cause massive capital flight, and how everything cool will happen in Austin and Miami instead of San Francisco and New York Real Soon Now because Socialism. Mostly this is cheap talk. They are mostly bluffing. The considerations matter on the margin, but not enough to give up the network effects or actually move.

They said SB 1047 would ‘destroy California’s AI industry’ when its practical effect would have been precisely zero. Many are saying similar things about Mamdani, who could cause real problems for New York City in this fashion, but chances are he won’t. And so on, there’s always something, usually many somethings.

So there is most definitely a ‘boy who cried wolf’ problem, but no, seriously, wolf.

I believe it would be a 100% full wolf even if you could pay in kind with illiquid assets, or otherwise have a workaround. It would still be obviously unworkable including due to flight. Without a workaround for illiquid assets, this isn’t even a question, the ecosystem is forced to flee overnight.

Looking at historical examples, a good rule of thumb is:

-

High taxes on realized capital gains or high incomes do drive people away, but if you offer sufficient value most of them suck it up and stay anyway. There is a lot of room, especially nationally, to ensure billionaires get taxed on their income.

-

Wealth taxes are different. Impacted people flee and take their capital with them.

The good news is California Governor Gavin Newsom is opposed, but this Manifold market still gives the proposed ‘2026 Billionaires Tax Act’ a 19% chance of collecting over a billion in revenue. That’s probably too high, but even if it’s more like 10%, that’s only the first attempts, and that’s high enough to have a major chilling effect already.

To be fair to Tyler Cowen, his analysis assumes a far more near term, very much like today scenario rather than Dyson spheres and galaxies, and if you assume AI is having sufficiently minor impact and things don’t change much, then his statements, and his treating the future world as ours in a trenchcoat, makes a lot more sense.

Tyler Cowen offered more of the ‘assume everything important doesn’t matter and then apply traditional economic principles to the situation’ analysis, try to point to equations that suggest real wages could go up in worlds where labor doesn’t usefully accomplish anything, and look at places humans would look to increase consumption so you can tax health care spending or quality home locations to pay for your redistribution, as if this future world is ours in a trenchcoat.

Similarly, here Garett Jones claims (in a not directly related post) that if there is astronomical growth in ‘capital’ (read: AI) such that it’s ‘unpriced like air’, and labor and capital are perfect substitutes, then capital share of profits would be zero. Except, unless I and Claude are missing something rather obvious, that makes the price of labor zero. So what in the world?

That leaves the other scenario, which he also lists, where labor and ‘capital’ are perfect complements, as in you assume human labor is mysteriously uniquely valuable and rule of law and general conditions and private property hold, in which case by construction yes labor does fine, as you’ve assumed your conclusion. That’s not the scenario being considered by the OP, indeed the OP directly assumes the opposite.

No, do not assume the returns stay with capital, but why are you assuming returns stay with humans at all? Why would you think that most consumption is going to human consumption of ordinary goods like housing and healthcare? There are so many levels of scenario absurdity at play. I’d also note that Cowen’s ideas all involve taxing humans in ways that do not tax AIs, accelerating our disempowerment.

As another example of economic toolbox response we have Brian Albrecht here usefully trotting out supply and demand to engage with these questions, to ask whether we can effectively tax capital which depends on capital supply elasticity and so on, talking about substituting capital and labor, except the whole point is that labor (if we presume AI is of the form ‘capital’ rather than labor, and that the only two relevant forms of production are capital and labor, which smuggles in quite a lot of additional assumptions I expect to likely become false in ways I doubt Brian is realizing) is now irrelevant and strictly dominated by capital. I would ask, why are we asking about the rate of ‘capital substitution for labor’ in a world in which capital has fully replaced labor?

So this style engagement is great compared to not engaging, but on another level also completely misses the point? When they get to talking downthread it seems like the point is missed even more, with statements like ‘capital never gets to share of 1 because of depreciation, you get finite K*.’ I’m sorry, what? The forest has been lost, models are being applied to scenarios where they don’t make sense.