Good news, we managed to make some cuts. I think?

-

California In Crisis.

-

Bad News.

-

Opportunity Knocks.

-

Government Working.

-

The Efficient Market Hypothesis Has Thoughts.

-

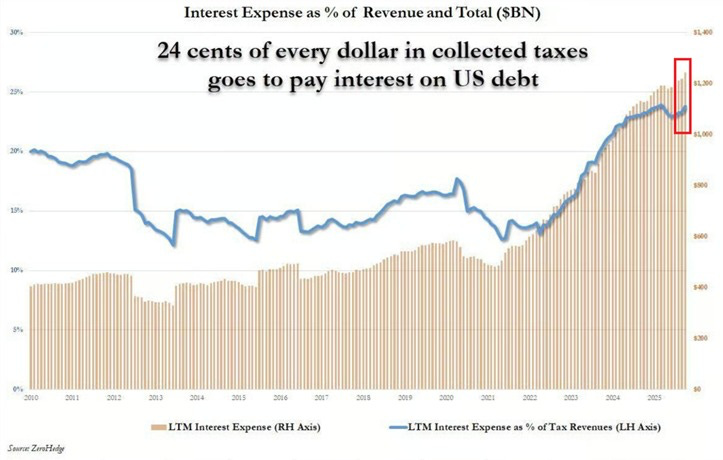

No All That Money Doesn’t Go To Pay Interest.

-

While I Cannot Condone This.

-

Burnout.

-

Good News, Everyone.

-

Good Advice.

-

For Your Entertainment.

-

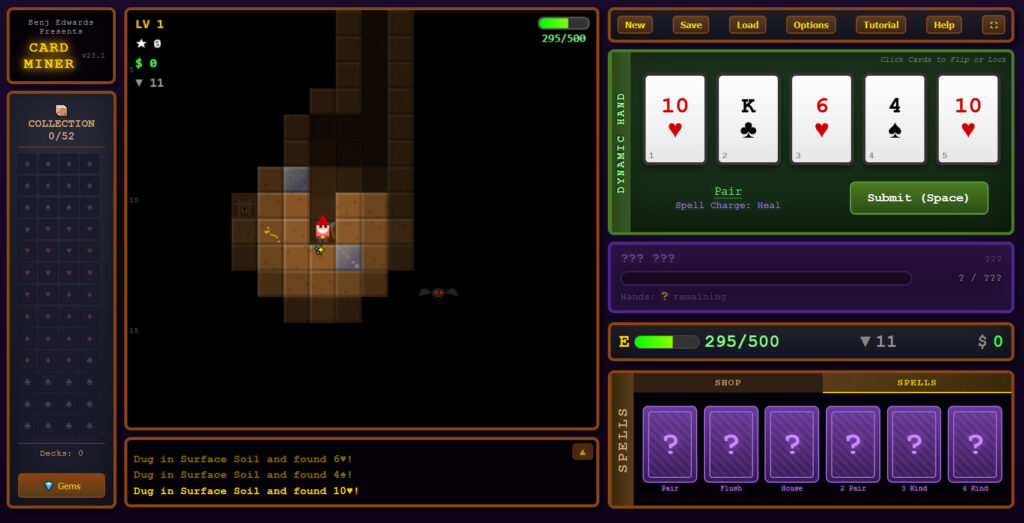

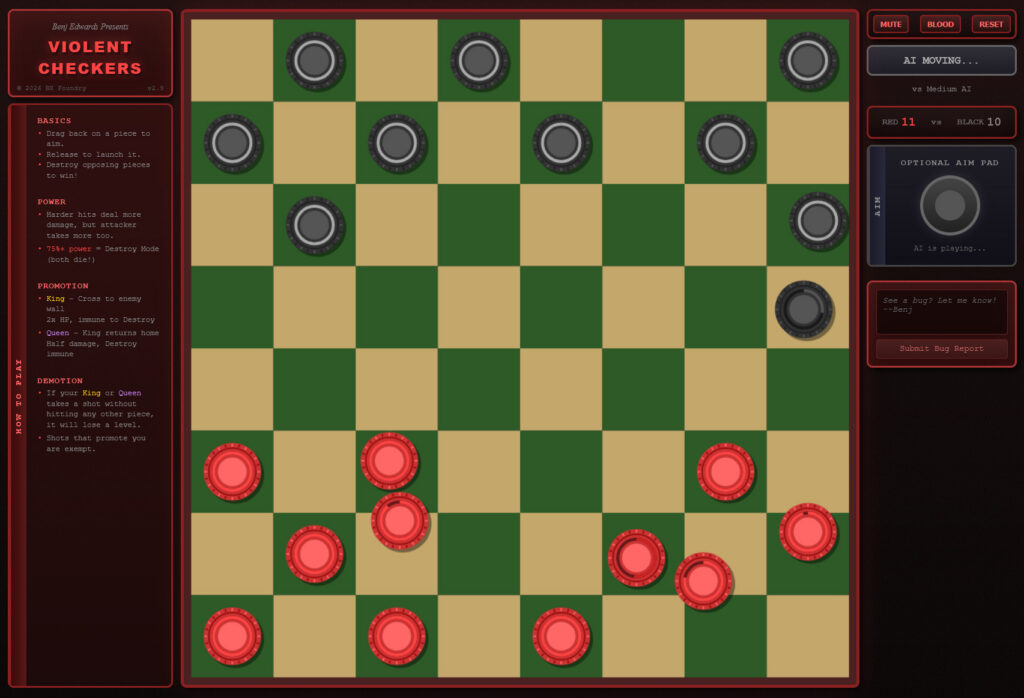

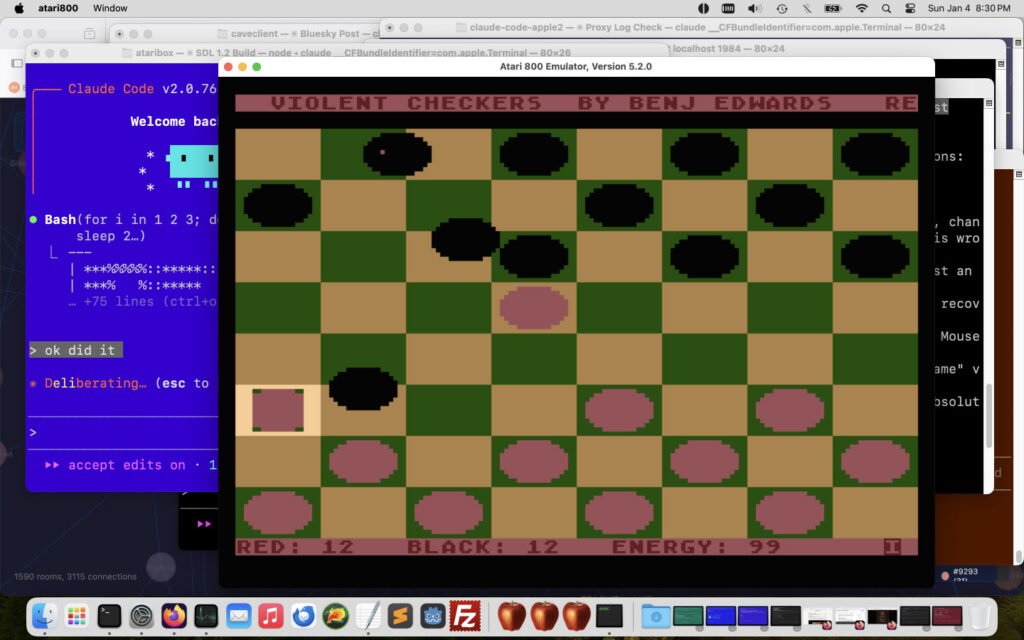

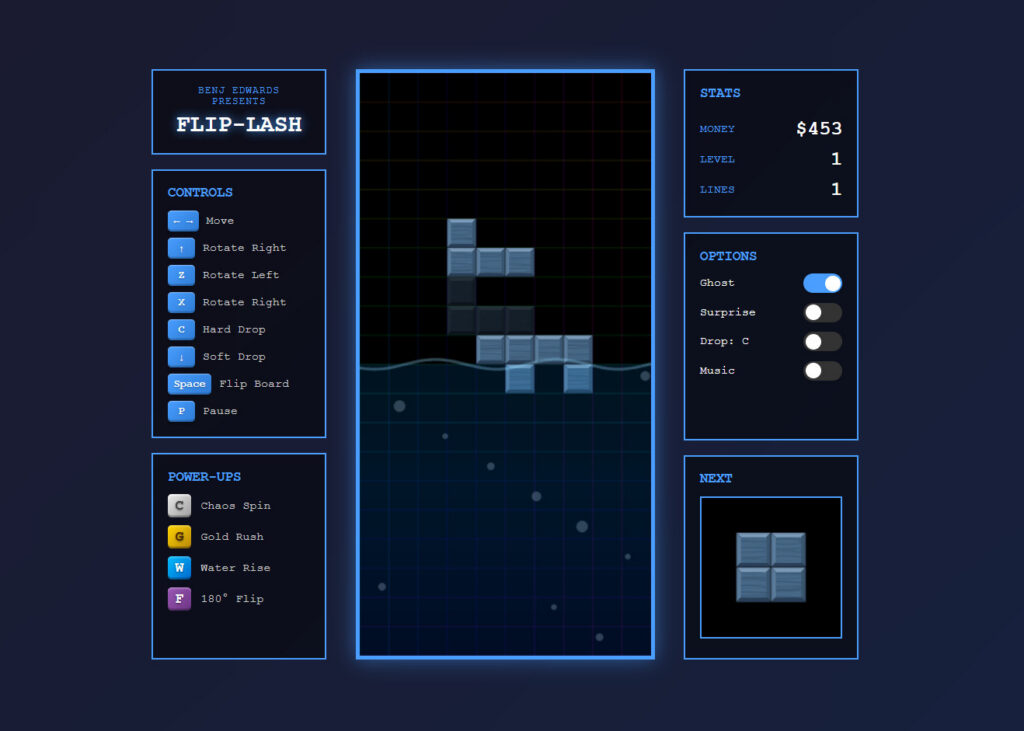

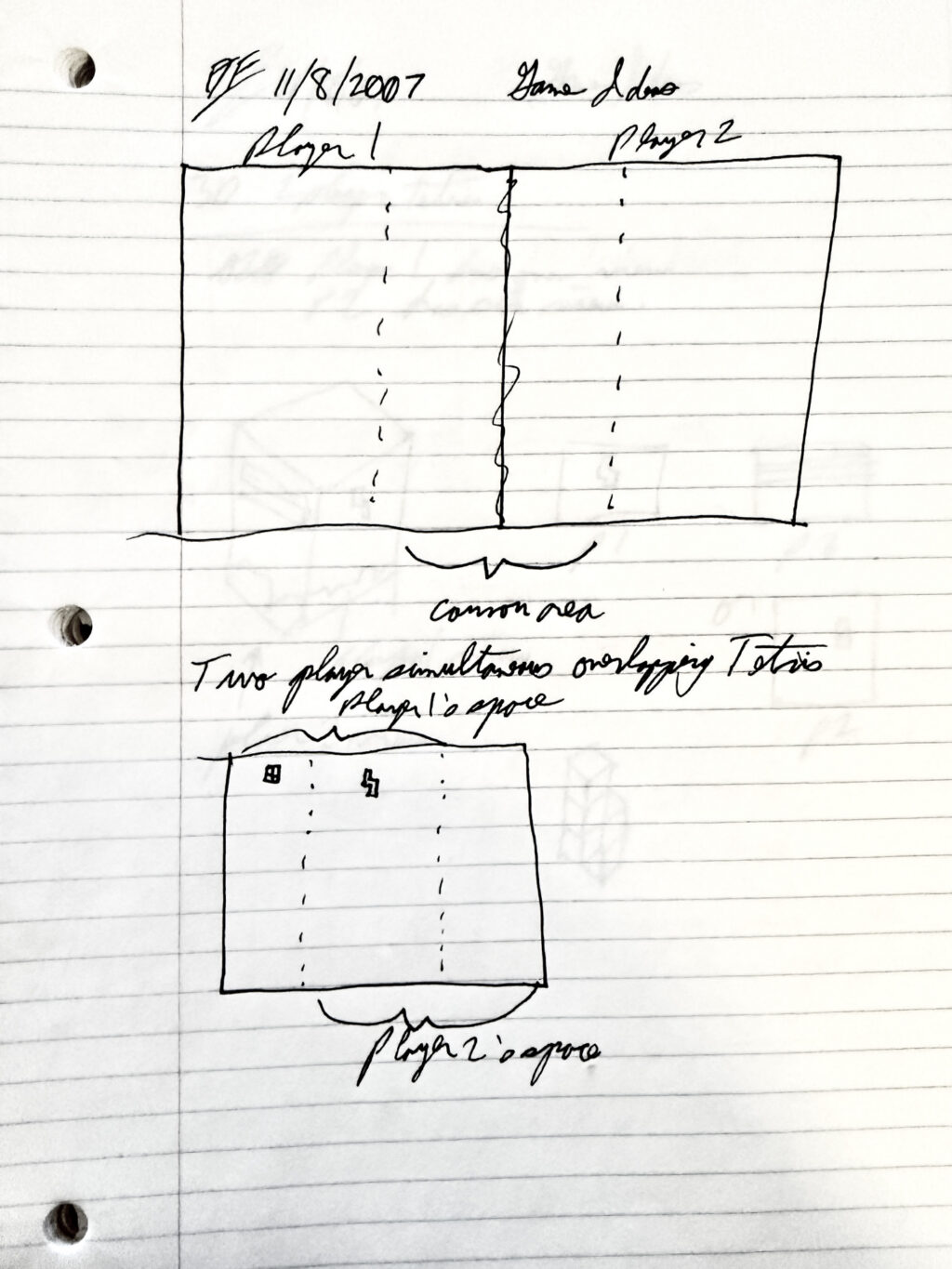

Gamers Gonna Game Game Game Game Game.

-

Sports Go Sports.

-

Antisocial Media.

I’ve written about this before, but it turns out it’s even worse than I realized.

California is toying with a 1.5% annual wealth tax on billionaires, sufficiently seriously that Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Peter Thiel have left the state as a precaution.

Teddy Schleifer: NEWS:

This would also include an annual 1% wealth tax on anyone over $50 million, per year, including on illiquid unrealized startup equity. That’s what takes this from ‘deeply foolish and greedy idea that will backfire’ to ‘intentionally trying to blow everything up to watch it burn.’

Garry Tan points out that as written the law would treat any supervoting shares as if they had economic value equal to their voting rights, which means any founders with such shares are effectively banned from the state. There are some other interesting cases, most notably Mark Zuckerberg.

Garry Tan is one of those with a history of crying wolf, but in this case? Wolf.

This one is really scary. Chances of this passing are up to 53%, and the ‘will this be on the ballet’ question is only at 61%, which implies that if this does make it to a vote then it will probably pass. Again, California needs to end propositions, period.

I presume that, if implemented, this would force the entire startup ecosystem, and likely all of tech, to flee the state. California is nice, but it’s not this nice.

They were forced to do this, since the proposal backdates the tax. Once you open that door, it’s time to leave. Even if this proposal fails, what about the next proposal? Or will everyone act like they do with AI risks, and say ‘well things are fine so far’ and put their heads back into the sand?

In a sane world this would be the death of California’s ballot proposal system.

The audacity of the lies around this one stood out to several who don’t say ‘lying’ lightly lighting.

Kelsey Piper: When I said this tax was a terrible idea a bunch of people smugly flocked to tell me how, since it was retroactive, there’d be no risk of billionaires moving to avoid it. But instead what this means is that the billionaires move even before we know whether it makes the ballot!

I remember people telling me that there was not typically very much capital flight in response to a modest increase in income tax rates and therefore we could be sure that there wouldn’t be any from a much much larger and less precedented tax.

There’s this specific kind of lying that is endemic on the policy left, where you make absolutely insane and obviously false claims but ground them by linking a paper to a very different situation where no one was able to detect much of an effect.

The lying on the right is a huge problem and I would say much worse, though usually slightly different in character. They just make stuff up, while libs will do the ‘link a study that doesn’t say that’ thing.

Patrick McKenzie: One is welcome to remember this for the next round of this game, since advocates certainly will not.

“But were they lying to us in the current round?”

Yes, obviously. YMMV on whether that should cost them points with you and yours.

Myself I favor an epistemic stance like “If one inadvertently says an untrue thing which is core to one’s argument one, on learning it was untrue, admits that and accepts a modest amount of egg on face. Orgs which do not embrace protocol get performance to contract, not trust.”

“Patrick you used the word ‘lying.’”

I did.

“You do not frequently deploy the word ‘lying.’”

I don’t.

… “Would you ever countenance a lie?”

I do like the formulation that a Catholic priest relayed to me when I was approximately seven: “Lies which offend God are sins. Not all lies offend God. You can reason and read about it more when you’re older.”

Things I feel very much and are worth a read: Jennifer Chen, my erstwhile contractor at Balsa Research, enters her Misanthropy Era.

Ubers and Lyfts are so expensive in substantial part because of a requirement for $1 million in insurance on all rides, in turn giving rise to fraud rings making a majority of the claims. In California, New York and New Jersey that includes $1 million in ‘uninsured motorist’ coverage, and therefore insurance takes up 30% of the cost of the ride, which seems obviously nuts.

Much of the gender pay gap is about the need to avoid sexual harassment and other hostile work environments?

Manuela Collins (from her paper): Individuals are willing to forgo a significant portion of their earnings—between 12% and 36% of their wage—to avoid hostile work environments, valuations substantially exceeding those for remote work (7 percent).

… Using counterfactual exercises, we find that gender differences in risk of workplace hostility drive both the remote pay penalty and office workers’ rents.

Inkhaven will return this April. That’s a residency at Lighthaven, where you get mentored by various writers (myself not included), and if you don’t post every day you have to leave. It costs $3,500 for admission plus housing and retrospectives and feedback look good. I think it’s pretty neat, so if you’re a good fit consider going.

Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen put out a call for new aesthetics, especially in architecture but open to all mediums, with grant sizes of $5k-$250k. What should the future look like?

I for one would like to put out a call for past aesthetics. I’m not saying past aesthetics were optimal, but today’s aesthetics suck and are worse. Past ones didn’t suck. So until we can come up with something better, how about we do more of that past stuff?

Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell asserts that he is facing threat of criminal indictment due to retaliation over his refusal to let Donald Trump dictate interest rates. A statement of support for Powell and condemning the criminal inquiry was signed by Ben Bernanke, Jared Bernstein, Jason Furman, Timothy Geithner, Alan Greenspan, Jacob Lew, Gregory Mankiw, Janet Yellen and others. It is hard to come up with an alternative hypothesis on the nature of this prosecution.

Senator Thom Tillis pledges to oppose the confirmation of all Fed nominees while this matter is pending. He serves on the Banking Committee, which is currently split 13-11. If no one is confirmed, then Powell would remain chair.

This means that not, unless you can come up with another explanation for why you would attempt to prosecute Jerome Powell over (checks notes) statements to Congress regarding a building renovation, only is Donald Trump trying to destroy the independence of the Federal Reserve, he is very clearly trumping up charges against those he thinks are standing in his way, as per his explicit other communications.

For those who need a reminder, if you cap credit card interest rates at 10%, that forces banks to severely restrict credit card access and make up that revenue in other ways, many consumers will be forced to use alternative mechanisms that often charge more, and we should expect consumers as a group to be a lot worse off. Don’t do this.

The UK sends one soldier to defend Greenland.

Barbara Tuchman (from The Guns of August, this is in 1910):

“What is the smallest British military force that would be of any practical assistance to you?” Wilson asked.

Like a rapier flash came Foch’s reply, “A single British soldier—and we will see to it that he is killed.”

Also, in terms of banning institutional ownership of homes, institutions own maybe 1% of single family homes, institutions of any size only hold 7%, the three institutions named as owning ‘everything’ by RFK Jr. in this context don’t directly own them at all (they own some interest in homes via REITs) and most definitely do not want to ‘own every single family home in our country.’ Banning institutions from owning such homes will make it harder to build or rent houses and it will generally make things worse.

If you are trying to figure out whether you should be happy ‘as a utilitarian’ with the United States taking out the de facto leader of Venezuela, contra Tyler Cowen you cannot only ask the question of whether interventions in this reference class lead to superior results in that particular country. The obvious first thing is you don’t know that you can expect results similar to the reference class, and the second is that counterfactuals are, as Tyler admits, very difficult to assess.

Even setting all that aside, this is the wrong question. You cannot only ask ‘does this improve the likely outcome for Venezuela?’ which requires considering the details of the situation and path chosen. You instead have to consider whether the decision algorithm that leads to such a removal leads to a better world overall, or at least you must consider the impact of this decision on all actors worldwide.

What Tyler Cowen is doing here is exactly the type of direct-consequence under-considered act utilitarianism that leads to problems like Sam Bankman-Fried.

So when Tyler asks ‘effective altruists, are you paying attention?’ to the fact that the direct consequences seem to Tyler to be positive, is he saying ‘you should be doing or trying to induce more immoral unconstitutional actions that are good on a direct outcome act utilitarian basis’ or is he (one might hope) saying ‘notice that you need to have virtue ethics or deontology, you make this kind of mistake all the time’? Or is he trying to make an ‘EA case for Trump’ of some kind or simply score points in some sense? I honestly can’t tell.

But no, I say, if you think this was an immoral unconstitutional action, the you should not approve of it, for that reason alone. That seems pretty simple to me. I certainly hope no one is making the case that taking immoral unconstitutional actions are a good idea so long as they produce a particular outcome that you like?

US government is planning to require tourists from over 40 countries to hand over 5 years of social media history, all email addresses and phone numbers used in the last 5 years, and the names and addresses of family members. A massive unforced error.

Your periodic reminder that many San Francisco programs, that spend quite a lot of money, cannot be explained as anything other than grift, and that nonprofits benefit from this grift actively suppress attempts to measure their effectiveness. The example here from Austen Allred is that there is a program, that costs $5 million a year, that housed 20 homeless alcoholics and served them alcohol with no attempt to get them to quit drinking. Do the math.

99.8% of Federal Employees Get Good Performance Reviews. The exception was the person in charge of performance reviews.

You’ll be able to fly without a REAL ID, but it will cost you $45. Grift ahoy.

Matt Levine points out that for most stocks it is hard to tell if they are likely to go up or down, but there are some stocks that a lot of investors think are hot garbage, sufficiently so that they have substantial borrow costs, and in general shorting them pays out about equal returns to the borrow cost, so presumably you don’t want to own them, especially if you’re not being paid the borrow cost.

Thus you can ‘beat the market’ at least a little via One Weird Trick, which is that you don’t buy those stocks. This is better than buying an ETF or other index fund that doesn’t follow that rule.

A lot of the reason I choose to buy individual stocks is the generalization of this. Even if I can’t ‘pick winners’ I trust myself to do better than random at identifying losers you don’t want to touch and then not touching them. Profitably shorting is hard, profitably ‘not longing’ doesn’t scale but is a lot easier and you’re still kind of short.

This also suggests a business opportunity. Why not create an ETF that is the broad US stock market, except it excludes hard-to-borrow stocks beyond some low threshold? If a stock becomes hard-to-borrow, it sells that stock until it becomes easy again. You would expect to consistently outperform. There wouldn’t be a strict index to follow, so it requires solving some issues, but seems worth it.

This is a bad presentation of information and everyone involved should feel bad.

Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah): Nearly a quarter of every tax dollar the federal government takes from you is now used just to pay *intereston the national debt

This will get worse as long as Congress pretends money is limitless—as it does when spending roughly $2 trillion more than it brings in each year

Should Congress cut down on spending? I believe they should, because we could be on the verge of the market charging a lot higher interest on government debt, and it is very important to reduce the risk of that happening.

Does this mean 25% of your tax dollar goes to interest? Absolutely not. That is not where the ‘money goes,’ even accepting that money is fully fungible.

The correct way to think about this is that what you care about is the ratio of debt-to-GDP, therefore:

-

There is a primary deficit, ignoring interest. It’s too big. We should fix it.

-

There is interest on the debt, and there is nominal economic growth.

-

To the extent that the interest on the debt exceeds the rate of nominal economic growth, the outstanding debt is getting worse over time over and above the primary deficit.

-

To the extent the interest is less than nominal economic growth, it is shrinking over time, counteracting some of the primary deficit.

-

If nominal growth sufficiently exceeded interest rates, say due to AI, in a sustained way, then we could handle any amount of debt that didn’t raise that interest rate.

-

The reason you still make sure you don’t go into too much debt eventually does raise the interest rate you pay, and can hit tipping points.

Household-to-government metaphors are often used in such spots. They can be misleading, but can also be good intuition pumps.

Right now:

-

Nominal GDP growth is about 4.6%.

-

The average interest rate on federal debt is 3.4%, since rates used to be lower.

-

If we refinanced all outstanding federal debt, at its original durations, using current interest rates, we would pay roughly 3.9%.

Thus, right now, not only is 25% of your tax dollar not paying interest on the debt, the de facto amount you pay is negative. If we balanced the primary budget, the debt would shrink over time as a percentage of GDP.

Our primary deficit is very high, and this means the deficit continues to expand as a share of GDP, perhaps dangerously high. But the interest burden, for now, is fine.

Scott Alexander gives us highlights on the comments from his vibecession post. My response to quite a lot of this is ‘see The Revolution of Rising Expectations sequence,’ and I am sad that he didn’t incorporate that into his updates here. A lot of people are clearly grasping at similar things.

I was especially disappointed by Scott’s continued emphasis on the math behind things like ‘real wages’ or inflation, whereas I spent a lot of the sequence emphasizing that this misses the measurement that matters most.

One point highlighted here is the Parable of Calvin’s Grandparents, where his grandfather worked terrible hours doing unpleasant work owning his own business, and pretty much never did anything besides work and never saw his kids aside from attending church. If you want to run a thankless small business (one person mentions a butcher) my understanding is you can absolutely make a solid living that way, it’s just not going to be fun and we don’t want to do that.

A look at a ‘sober house’ for sports bettors.

A good question:

Dean Ball: I really wonder how many uber black drivers in dc nyc and sf are intelligence assets. So many people I know have extremely sensitive conversations on the phone while in Ubers (guilty).

Plausibly yet another benefit of robotaxis!

I would be surprised if Uber or those within Uber were found to be intentionally pairing the right people with compromised cars or drivers, but not shocked.

Back in 2022 Emmett Shear defined three of the types or triggers of burnout:

-

Permanent on-call. Too much time always-on without breaks.

-

Broken steering. Your actions seem to not accomplish anything or not matter.

-

Mission doubt. You don’t understand why you’re doing this.

Cate Hall offers some additional items:

-

Shifting goals, or empathy, pulling in too many directions in a row or at once.

-

Emergencies that aren’t genuine, due to poor leadership or time management.

As Shear emphasizes, this is not about working too hard. You don’t get burnout from ‘working too hard,’ you get it from specific mismatches.

As Hall emphasizes, once you sense oncoming burnout, the sooner you deal with it and treat it like an emergency the better, whereas if you try to power through it will only get worse, and you’ll lose more time in recovery and risk a larger sphere of aversion afterwards. In some cases, if you wait too long, you might never recover or it might become universal. And it isn’t stress.

I’ve certainly known burnout. I’ve burned out in a big way three times, once from Magic: The Gathering from repetition and mission doubt, once after MetaMed from basically all of it, once at the end of Jane Street due to a form of permanent on-call. I’ve also ‘locally’ burned out plenty of times, and back during my Magic career I’d sometimes burn out on testing a format or matchup or within a tournament. I notice that I can be short term burned out on ‘effort posting’ at times but am basically never burned out from general posting, and that when it’s an issue ‘don’t do any writing’ isn’t the way to fix the problem.

I notice that burnout is fractal in time. It can be this big thing where you burn out from a years long job and need to quit, or (at least in my experience) you can be burned out today, or for an hour, or a minute.

Cate presents burnout as breaking the pact between ‘elephant and rider’ – the conscious part of your brain wants to keep going but the rest of you isn’t having it. The elephant isn’t getting what it needs. It stops listening and goes on strike.

Cate’s solution is to figure out what your elephant needs, and provide it. Sometimes that is rest. Other times it isn’t, or sometimes ‘real rest’ requires not having to come back to the problem later.

Cate lists credit, autonomy and money as possibilities. I would add intellectual stimulation, or variety or novelty or play, or experiences of various sorts, or excitement, or a sense of accomplishment? In my wife’s case it seems to often be a change of scenery, whereas my elephant does not care about that at all.

We’re so back! As in, Polymarket is returning to the United States.

Many are attempting to block Polymarket by complaining that it allows insider trading, and this is ‘deceptive.’ Robin Hanson points out that it’s on you to keep your secrets, and there is nothing deceptive about trading on info. I agree, so long as it is clear that insider trading is permitted. Insider information is deceptive if and only if the traders are being told that there won’t be insider trading. That promise is valuable, but so is getting insider information. There is room for both market types.

Scott Alexander points out we now have lots of liquid prediction markets on non-sports events, via Polymarket and Kalshi, yet the world hasn’t changed much. He asks why, and offers several partial explanations.

-

There’s definitely a lot of ‘people have not caught on yet,’ also known as a pure diffusion problem. In some narrow cases, like elections, the odds are being accepted and mainstreamed the way they are in sports, but it’s a slow process.

-

As in AI, the fact that the future is unevenly distributed does not mean it isn’t here. Yes, prediction markets matter, and have definitely informed my actions.

-

I agree that for many purposes, 20% and 40% are often ‘the same number,’ and people are notoriously bad about tracking and learning from changes in probabilities (see the stock market), so prediction markets aren’t having that much impact on decisions unless we previously had very large uncertainty.

-

Alternatively, people often simply do not care about the odds when making decisions. This is the Han Solo Rule: Never tell me the odds.

-

I think the big one is that Polymarket hasn’t asked enough of the right questions. This is a structural and cost issue, combined with a grading criteria issue, not a failure of imagination. Markets that are long term, or conditional, or potentially ambiguous, or worse a combination of all three, are very hard to make work.

The good news is that these problems, especially #5, become less binding as volume goes up and there are more profit centers to subsidize esoteric markets, but it’s a slow process.

Scott Alexander offers a Hanson-like proposal for a set of conditional markets to control for various factors, allowing us to make causally dependent conditional markets. Something like that would work, but it requires 4+ markets all of which are conditional and liquid. That means either vastly more interest in such markets (and solving the capital lock-up issues), or it means massive subsidies.

On the question of grading criteria, for my own markets I’m moving towards ‘use the best definition you can and then say you’ll resolve via LLM’ since that is objective in its own way, although I am not yet being consistent about this. But when I see obvious ambiguous cases? Yep, then I’m going to take the cowards way out in advance.

Most complaints come from a very small number of people, often a majority come from one person. The classic example cited is noise complaints against airports, but this extends to things like sex discrimination, where one person is 10%-30% of all complaints. Alas, with AI, it is increasingly possible for a complainer to be outrageously ‘productive’ if they choose this. Levels of Friction on scaling your complaints are dangerously low.

The obvious solution is you do at least one of these and ideally both:

-

You make it expensive to keep doing this, or impose a quota.

-

You stop listening.

That’s what we do in ‘normal life’ when someone complains a ton and they don’t check out. Once we decide their complaints don’t have merit, we ignore them, and we socially punish them if they don’t stop.

Important thing to remember from Vitalik here:

Nathan Young: I have no time for criticism of Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality that doesn’t acknowledge it’s one of the most read Harry Potter fan fictions in the world. Yud is a high tier writer. Get over it!

Vitalik Buterin: If you’ve heard of someone, that means they won a game (getting famous enough that people like you know of them) that millions of people would really love to win, but could not figure out how to.

The celebrities, authors, politicians, influencers you hate are NOT talentless – much the opposite.

Maybe their talents or their ideas are very misaligned with the type of talent or ideas that improve the world – often true – but that’s a different argument.

Lock: You can dislike their impact but pretending they got there with zero talent is just coping.

Luck helps a ton, you don’t win a giant tournament without some amount of luck, but at higher levels no amount of luck is sufficient. If you don’t also have talent, you lose.

Swearing makes you temporarily physically stronger and more able to endure physical pain. Robin Hanson never stops Robin Hansoning so he asks why we don’t thus encourage swearing.

Paul Graham: I was thinking about this a couple days ago when I banged my head on one of the charming beams in my office.

Seal of the Apocalypse: Does this work in people who swear all the time?

Robin Hanson: Good question.

I predict that the value of swearing is a proxy for the relative intensity of expression. Swearing the way you usually do won’t help you. You could swear in a different way than you typically do, that differentiates it from your casual swearing, and that could work. But if you do the same thing you do all the time, that loses its power.

Ramit Sethi: Wisdom from a wealthy friend who owns a $10+ million house in SoCal:

“When you’re young, you want the big house. Now that I have it, it’s too much work to maintain. I just want a small apartment now. But for people like us, you have to get it to really understand that”

I’m less interested in this as an example of, “See! You don’t actually need fancy things” which is a very popular (and in my opinion, boring) frugality message in America

I’m MORE interested in this as a message specifically for high achievers: She correctly notes that high achievers WANT to achieve a lot and, when they do, they often realize the achievement itself was never the goal. But until they achieve it, they will never truly understand it

robertos: the house as a $10m experiment in reverse engineering your own taste. you have to pay the tuition to learn you didn’t want it. most people never get expensive enough to discover what they actually want

EigenGender: “I just need to do this once to prove that I can” is a surprisingly effective frame for lots of goals

There’s merit in doing things once to prove that you can or know that you did. There is also merit in doing things once to prove that you don’t want to do them a second time, or to not regret having not done them, or for the story value of having done it once. Usually not $10 million worth of merit, but real merit.

India rapidly getting modern amenaides, as in rural vehicle ownership going from 6% to 47% in a decade, and half of people having refrigerators, and 94% have mobile phones. You’ve got to admit it’s getting better, it’s getting better all the time.

If a rule needs to exist for incentive reasons, but is counterproductive in a given situation, it is good to be able to waive it.

The Husky: Anonymous: I work at a public library. A teenage boy came to the desk. He looked nervous. “I found this,” he said. He put a copy of Harry Potter on the counter. It was lost 3 years ago. It was battered. “I stole it,” he admitted. “We didn’t have money for books. But I read it. I read it ten times.”

He pulled out a crumpled $10 bill. “For the fine.” I looked at the computer. The fine was way more than $10. I looked at the kid. He was honest. He was a reader. I took the $10. “Actually,” I said, “The fine is exactly zero dollars during Amnesty Week.” (There is no Amnesty Week). I pushed the money back to him. “Buy your own copy,” I said. “And come back. We have the sequel.” He comes in every Tuesday now. Libraries are for reading, not for accounting.

Robin Hanson: ”Rules are for people I don’t like.”

Confidence is highly correlated with all forms of success. It is hard to think of a measurement more confounded to hell, but some of the experiments do suggest causation. The suggested actions for cultivating confidence are:

-

Act the part, fake it until you make it.

-

Reframe anxiety as excitement, the one that has an experimental study attached.

-

Visualize the win.

-

Short circuit to halt any post-event spiraling.

-

Build a success story, get yourself small wins to build upon.

Scott Alexander reports on the state of his toddlers, which he calls a ‘permanent emergency.’ Sounds about right.

BOSS: one topic that no one mentions is that you should be terrified of never figuring out what you are NATURALLY talented at. marketing, sales, woodworking, playing guitar… it doesn’t matter. put yourself out and find it asap. giving yourself enough time to reach your max potentional

Adele Bloch: ask yourself – what does it feel like everyone else is weirdly bad at? that’s usually an indicator of where your natural strengths are

Weirdly is a feature of you, not of the world, but the info you seek it about you, too.

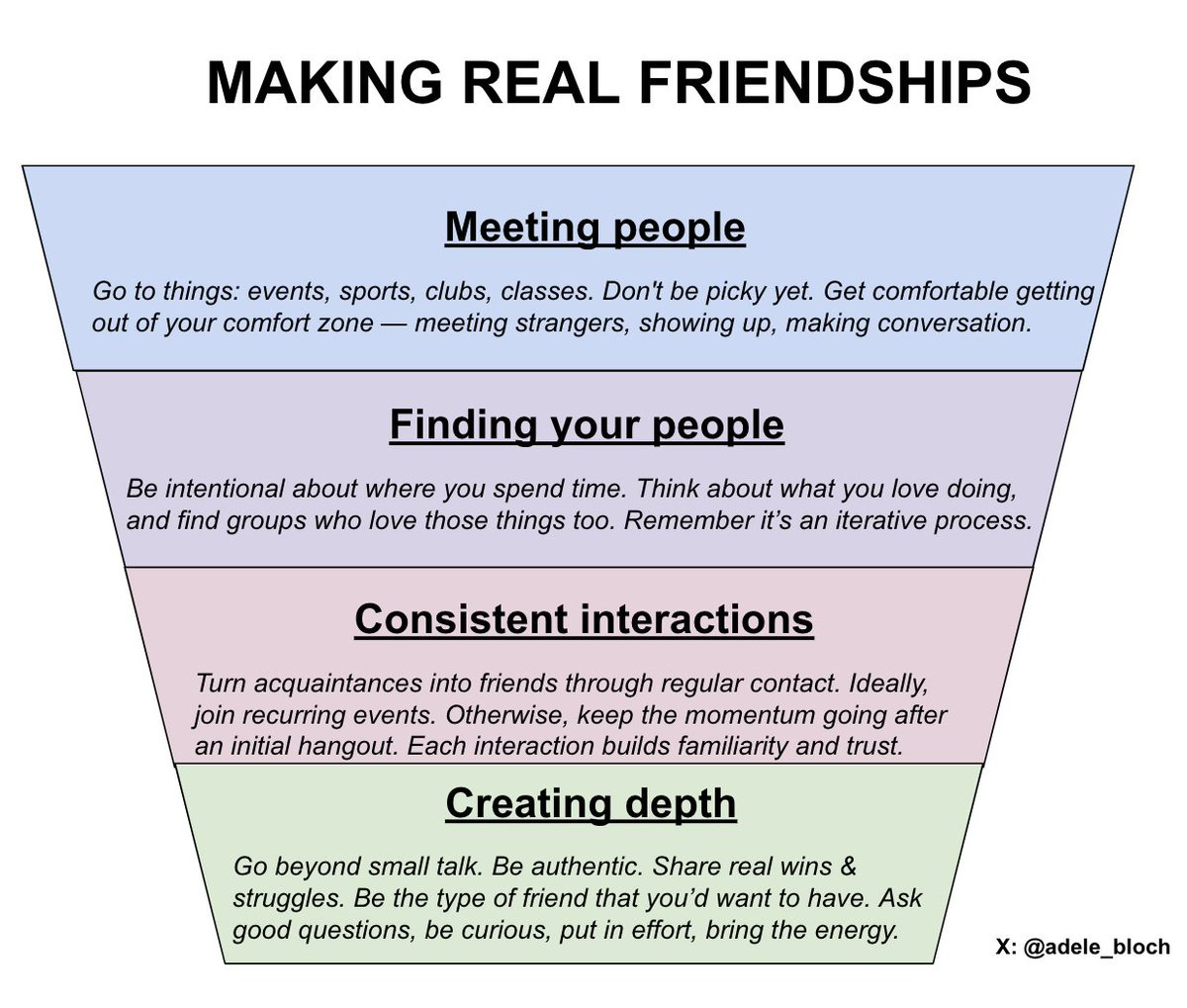

Adele’s entire feed seems to be about, essentially, ‘it is hard to make friends but it is not this hard all you really have to do is get off the couch and off your phone and Do Things, meet people and then keep doing things with them.’

I couldn’t follow her because she repeats herself so much, but it’s a great core message.

This review from Scott Sumner explains perfectly why our ratings don’t correlate:

Scott Sumner (his reviews are out of 4.0):

Resurrection (China) 4.0 Finally, a new film lived up to my expectations. I’m not quite sure what this film is about, as I was so busy being astonished by the cinematography that I missed many of the subtitles. (Oddly, the audience for this Chinese language film was mostly white, in one of America’s most Chinese counties.) Bi Gan seems to have been influenced by everything from Méliès’ silent film to Joseph Cornell’s magic boxes to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times. It’s so gratifying to see a director give us something new. This might end up being my favorite film of the decade. A shout out to cinematographer Dong Jingsong, who also filmed Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

The 30-minute long take at night in a rundown Yangtze river town reminded me of when my wife and I visited Wanxian one evening back in 1994. It was a surreal experience as the city would soon be flooded by the Three Gorges Dam and the place seemed like a decaying cyberpunk stage set.

or simply, later:

I tend to prefer East Asian cinema over Western films because the focus is more on visual style, rather than intellectual ideas.

‘I gave this film a perfect score without knowing what it was about’ is not a thought that would enter my mind. I didn’t doubt, reading that, that the cinematography was exceptional but I noticed that I expected the movie to bore me if I saw it. But then Tyler Cowen also praised it, and Claude noticed it was playing a short walk away.

So I saw Resurrection, and actually, yes, it’s the best film of 2025, and I wrote this:

Scott Sumner said he wasn’t quite sure what this film was about and still called it potentially his favorite film of the decade. I didn’t understand how both could be true at once. Now I do.

In terms of Sumner’s preferences, cinematic Quality, especially cinematography and visual style, I think this is the best film I’ve ever seen, period. As purely a series of stunning shots and images, even if it hadn’t come together at all, this would already be worthwhile. Which is something I basically never say, so it’s saying a lot, although maybe I can learn. It’s good to appreciate things.

And yes, the whole thing is on its surface rather confusing in terms of what it is actually about until it clicks into place, although you can have a pretty good hunch rather quickly.

Then most of the pieces did come together on two levels, including the title, with notably rare exceptions where I assume either I’d get it on second viewing or I lack the historical or cultural context. And this became great.

She says you don’t even know her name. I think you do know.

I do think to work fully this needs to be in a theater, it’s very visual and you need to be free of distractions.

The more I reflect on the experience, I agree with Tyler Cowen that seeing it in a theater really is a must. The more you are going for cinematography and Quality, the more you need a theater, and I think this applies even more than it does to the big blockbuster special effects movies.

If I had no idea what this film was about, or thought the thing it was trying to say was dumb, where would I put it on the cinematography and quality alone? On reflection I think I’d rate that experience around a 4 out of 5. I will add that yes, it is in part a love letter to film, that’s obvious and not a spoiler, but it is another thing, too.

Sumner also reviewed two movies I’ve seen recently, Sentimental Value (3.8) and One Battle After Another (3.7). I don’t have either movie that high, but neither score surprised me, and both seem right given what he values.

Tyler Cowen picks the movies he liked in 2025 without naming any he finds great in particular. He calls it one of the weakest years for movies in his lifetime. I found several of his picks underrated (House of Dynamite, Oh, Hi, The Materialists) but they shouldn’t make such lists in a strong year. The picks I actively disagree with are highly understandable and I’m in the minority on those.

Matthew Yglesias offers his favorite movies of 2025.

Rolling Stone best movies of 2025. They called it a ‘truly great year for great movies, period’ which I find hard to take seriously.

The New Yorker lists its best movies of 2025, and calls it a ‘brilliant year for movies.’

53 Directors Pick Their Favorite Films of 2025. There’s a clear pattern of choosing ‘this movie had very good direction’ as the central criteria. Makes sense. I respect the hell out of those here who were willing to go against this, such as Paul Feig.

In general, the correlation between ‘who you would give Best Director’ and ‘what you think is the best movie’ is very high. I would say far too high, that this is letting Quality override other movie features and this is a mistake.

Variance in such lists is also very high. Almost every list will have something that seems like a mistake, and include many movies I have not seen.

There really are a lot of movies. As of writing this I’ve seen 55 new movies in 2025, and even with some attempt to see the best movies (and admittedly some cases where I wasn’t trying) that still doesn’t include that many of the movies these lists include.

Thus, there are four types of disagreements with such lists.

-

I haven’t seen the movie. Maybe you’re right.

-

I have seen the movie, I disagree with you, but I get it. If you think One Battle After Another or Sinners or Weapons was great, I get why you would think that, in that order. They ooze ‘this is a really good movie’ but didn’t work for me.

-

I have seen the movie, I disagree with you, and you’re wrong. Two lists had The Phoenician Scheme, and I’m sorry, no, there’s some great moments and acting in it but overall it’s not there and you have to know that.

-

You’re missing a movie that you can’t have missed, and this isn’t merely a matter of taste, it both oozes great movie and is actually great, so you’re simply wrong, then this subdivides into ‘the world is wrong’ and ‘no it’s just you that’s wrong.’

Matthew Yglesias talks himself into the Netflix-Warner merger. He points out that many IPs might transfer from primarily movie IP to primarily TV show IP, and my response to that is: Good. TV lasts longer and has a bigger payoff, and movies rely too much on existing IP. It’s only bad if Netflix-Warner actively means theaters go out of business, which would indeed be terrible.

The movie business is weird. I don’t understand why, here in New York, you have tons of movie theaters and they all play the same new movies all the time for brief windows, and old movies only get brought back for particular events. Shouldn’t the long tail work in your favor here, especially since the economics of that favor the theater (they keep a much bigger cut)? And why shouldn’t Netflix want all their movies in theaters whenever possible? Are you really going to not subscribe to Netflix because you instead saw Knives Out on a bigger screen?

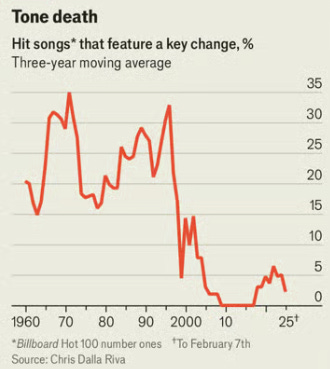

New music no longer involves key changes.

Any given song probably doesn’t want a key change. If your hit songs basically never key change, that seems like an extremely bad sign.

Given both Tyler Cowen and Scott Sumner mentioned it in their list of the best art of the 21st Century, I will note that while I did enjoy much of The Three Body Problem (my review is here) and found many ideas interesting, and I’d certainly say it’s worth reading, we’re all in trouble if that’s one of the best books over a 25 year period.

Ben Thompson goes on a righteous rant about how Apple does not understand how to create a good sports experience on the Apple Vision Pro. He is entirely correct. The killer product is that you take cameras, you let a fan sit in a great seat, and let them watch the game from that seat. That’s it. Never force a camera move on the viewer. That’s actively better than doing more traditional things.

You can improve that experience by giving the fan the option to move seats if desired, and giving them the option for a radio-style broadcast, and perhaps options for superimposing various statistics and game state information on their screens. But keep it simple.

If you miss MTV, there’s MTV Rewind.

Ondrej Strasky report on the Arena Championship, where he played Necro reanimator in Timeless.

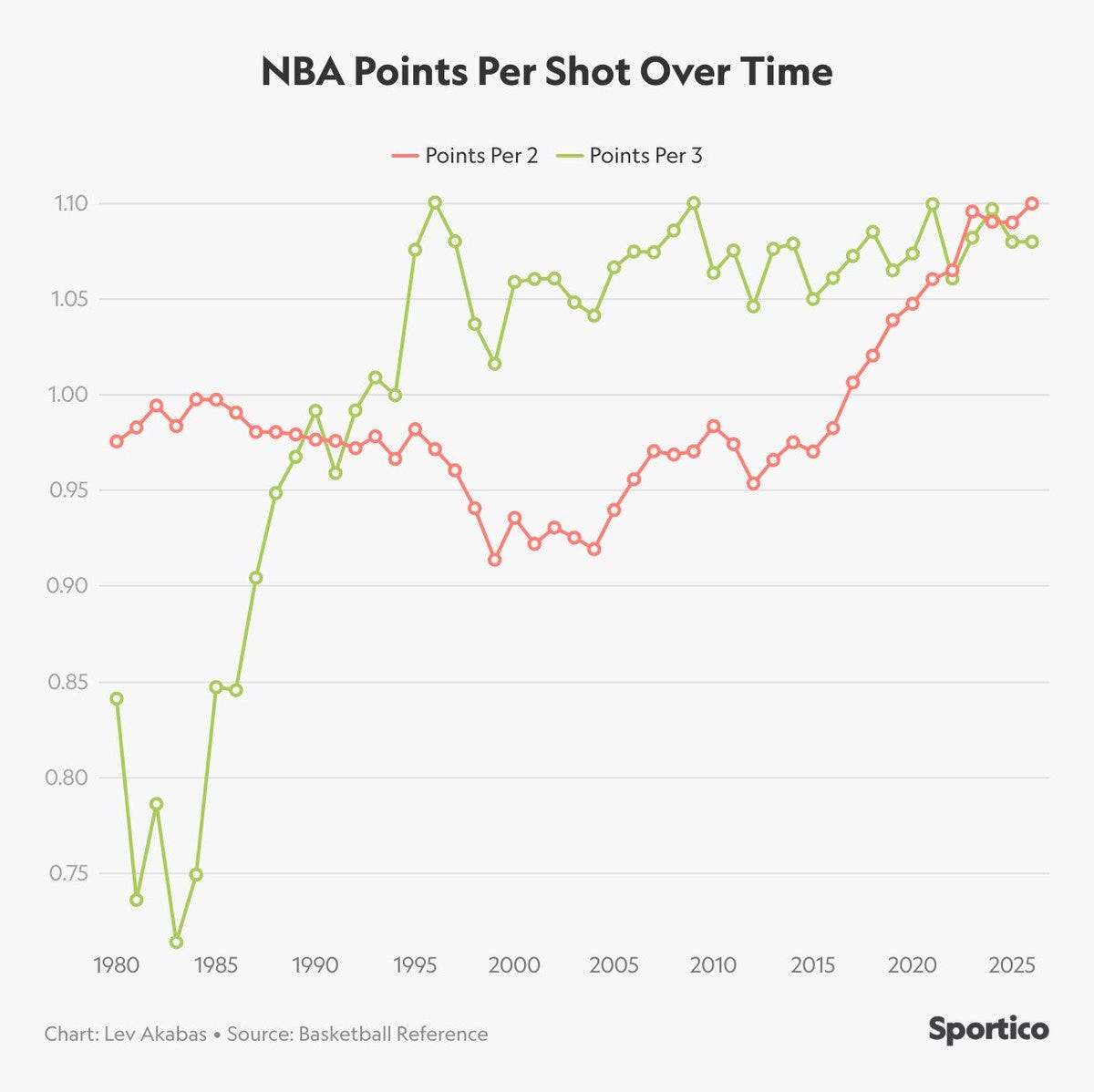

Two point attempts in the NBA now pay off better than three point attempts.

The equilibrium is that 2s should be worth substantially more than 3s. 2s have much higher variance than 3s. There are layups and dunks worth almost the full 2 points, whereas no 3 is ever that great and it’s almost always possible to get a 3 that isn’t that bad, if you can’t do better.

If you insist upon using any Twitter algorithm, check your ‘Twitter interests’ page and unclick everything you don’t want included. My list had quite a lot of things I am actively not interested in, but I didn’t notice because I never use algorithmic feeds.

Thebes gave us that tip, along with using lists for small accounts you like and aggressively and repeatedly saying ‘not interested’ in any and all viral posts.

Elon Musk is threatening to turn the Twitter algorithm over to Grok again.

Benjamin De Kraker: Ok, but where does “people you follow” fit into this process?

DogeDesigner: Elon Musk explains how the new Grok powered 𝕏 algorithm will work:

• Grok will read every post made on 𝕏 i.e over 100M posts daily.

• After filtering, it will match content to 300M to 400M users daily.

• Goal is to show each user content they are most likely to enjoy or engage with.

• It will filter out spam and scam content automatically.

• Helps fix the small or new account problem where good posts go unseen.

• You will be able to ask Grok to adjust your feed, temporarily or permanently.

So there it is. Direct engagement maximization on a per-post basis, and except for asking Grok to adjust your feed it will completely ignore anything else, and especially will not care about who you follow.

Elon Musk promises they will open source the algorithm periodically. At this point we all know how much that promise is worth.

If you want a social network to succeed in the long term you need to, as per Roon here, foster the development of organic self-organizing communities, centrally embodied by the concept of Tpot (as in ‘that part of Twitter’) for various different parts. If you do short term optimization you get slop and everything dies, and indeed even with the aggressive use of lists to avoid the algorithm it is clear Twitter is increasingly dominated by slop strategies.

A fun fact: Meta estimates it is involved in 1/3 of all successful scams in America (original video source) and Meta is basically doing the ‘we are making more money from allowing scams than we will be fined for knowingly allowing the scams’ calculation and knowingly allowing a lot of scams. I wonder how much they valued what would happen when people noticed all the scams? What will happen?

Robert Wiblin frames this as a ‘WTF’ moment, Dan Luu does not find it surprising and notes that whenever he tries clicking ads he finds a lot of scams, and notes that big companies have a hard time doing spam and scam filtering because they present too juicy an attack surface. In this case, the WTF comes from Meta clearly having the ability to do much better at preventing scams, seemingly without that many false positives, and choosing not to because the scammers generate ad revenue.

Elon Musk is once again making Twitter worse. Every time you load the page it will force the For You tab of horrors onto you, forcing you to reclick the Following button, and it may not be long before it is impossible to switch back. On Twitter Pro, you cannot switch back – the following tab is a For You no matter what you click on.

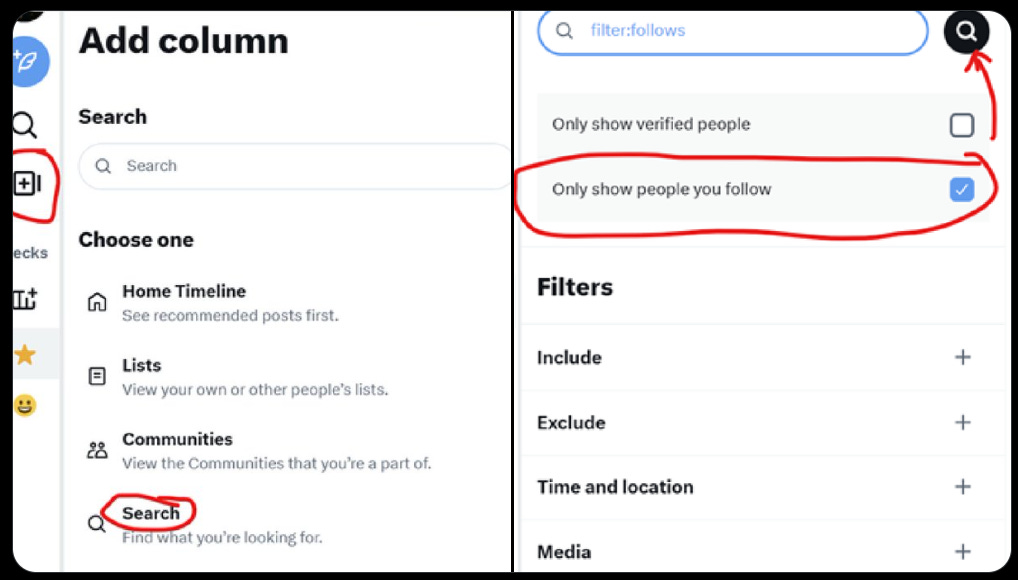

Good news, there is a solution, it’s a hack but it works:

Warren Sharp: tweetdeck’s home column being permanently stuck on the “for you” option despite selecting the “following” option is a development I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

…if your home tab is now full of “for you” recommended posts and you can’t see only people you follow, do this:

1. hit “add a new column”

2. hit the “search” option

3. check the box “only show people you follow”

4. leave the search field blank

5. hit the search button

boom

new column with only people you follow. Make sure at the top it says “latest” and you’ll get your old “home” column with it only pulling up people you are following

My solution, which was a bit more convoluted, was to vibecode a feature in my Chrome Extension that automatically moved all my followers into a list, and then added a feature to also add members from other lists, combined my two lists I check and my followers into one list, and presto.

Fun tidbit: Nikita Bier, basically in charge of making Twitter featuress, called PMs ‘not real.’ It shows.

Vitalik Buterin calls on Elon Musk to use Twitter as a global totem pole for Free Speech but also turning it into a death star laser against coordinated hate sessions, with his core example being hate directed towards Europe. As Vitalik notes, Europe, including both the UK and EU, have severe problems, but the rhetoric about them seems rather out of hand on Twitter.

Vitalik Buterin: I think you should consider that making X a global totem pole for Free Speech, and then turning it into a death star laser for coordinated hate sessions, is actually harmful for the cause of free speech. I’m seriously worried that huge backlashes against values I hold dear are coming in a few years’ time.

He’s clearly actively tweaking algorithms to boost some things and deboost other things based on pretty arbitrary criteria.

As long as that power lever exists, I’d prefer it be used (without increasing its scope) to boost niceness instead of boosting ragebait.

First best solution is to have Twitter run purely on an algorithm, and Elon Musk can either change the algorithm or use his account like everyone else.

Second best solution is to use the power for good.