Google quantum-proofs HTTPS by squeezing 15kB of data into 700-byte space

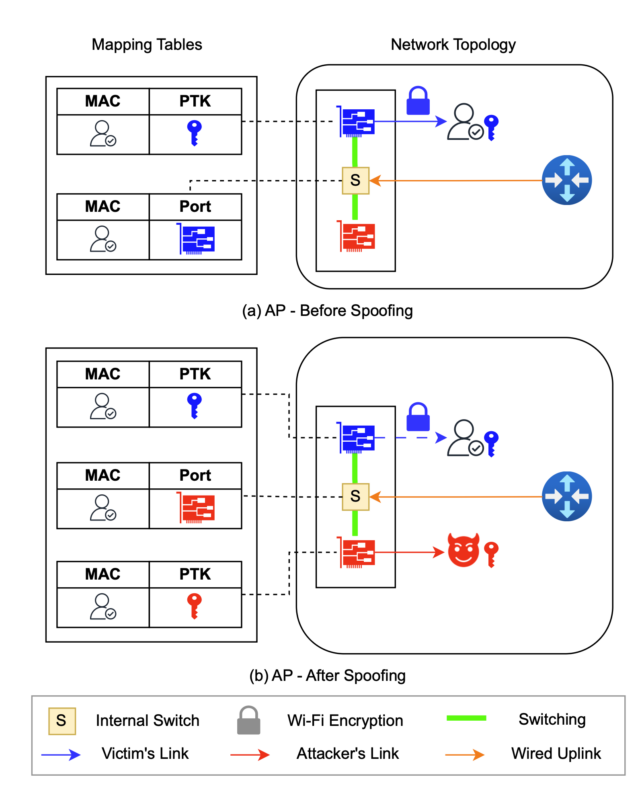

Google and other browser makers require that all TLS certificates be published in public transparency logs, which are append-only distributed ledgers. Website owners can then check the logs in real time to ensure that no rogue certificates have been issued for the domains they use. The transparency programs were implemented in response to the 2011 hack of Netherlands-based DigiNotar, which allowed the minting of 500 counterfeit certificates for Google and other websites, some of which were used to spy on web users in Iran.

Once viable, Shor’s algorithm could be used to forge classical encryption signatures and break classical encryption public keys of the certificate logs. Ultimately, an attacker could forge signed certificate timestamps used to prove to a browser or operating system that a certificate has been registered when it hasn’t.

To rule out this possibility, Google is adding cryptographic material from quantum-resistant algorithms such as ML-DSA. This addition would allow forgeries only if an attacker were to break both classical and post-quantum encryption. The new regime is part of what Google is calling the quantum-resistant root store, which will complement the Chrome Root Store the company formed in 2022.

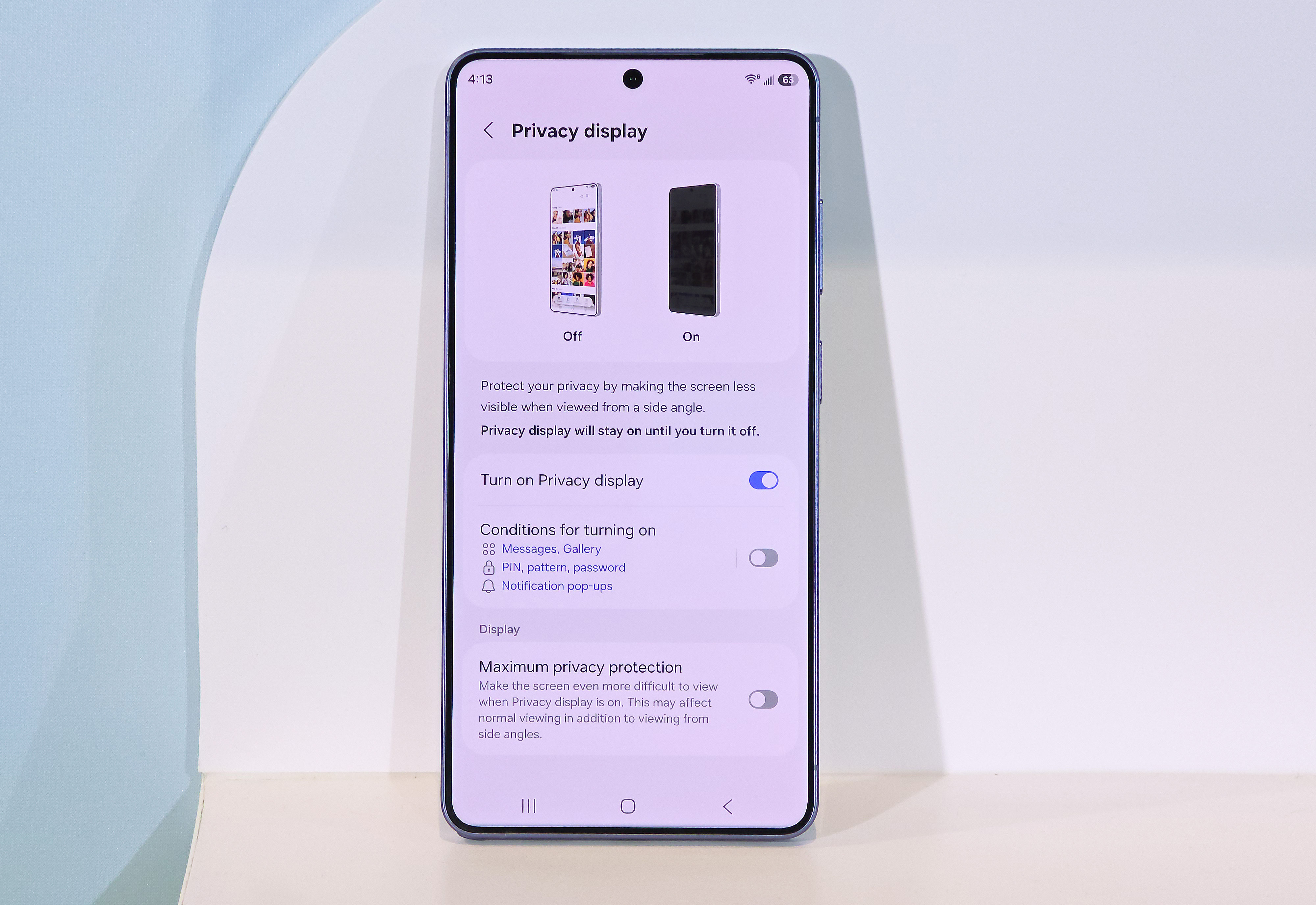

The MTCs use Merkle Trees to provide quantum-resistant assurances that a certificate has been published without having to add most of the lengthy keys and hashes. Using other techniques to reduce the data sizes, the MTCs will be roughly the same 4kB length they are now, Westerbaan said.

The new system has already been implemented in Chrome. For the time being, Cloudflare is enrolling roughly 1,000 TLS certificates to test how well the MTCs work. For now, Cloudflare is generating the distributed ledger. The plan is for CAs to eventually fill that role. The Internet Engineering Task Force standards body has recently formed a working group called the PKI, Logs, And Tree Signatures, which is coordinating with other key players to develop a long-term solution.

“We view the adoption of MTCs and a quantum-resistant root store as a critical opportunity to ensure the robustness of the foundation of today’s ecosystem,” Google’s Friday blog post said. “By designing for the specific demands of a modern, agile internet, we can accelerate the adoption of post-quantum resilience for all web users.”

Post updated to correct reported sizes of various items.

Google quantum-proofs HTTPS by squeezing 15kB of data into 700-byte space Read More »