We saw the heart of Pluto 10 years ago—it’ll be a long wait to see the rest

A 50-year wait for a second mission wouldn’t be surprising. Just ask Uranus and Neptune.

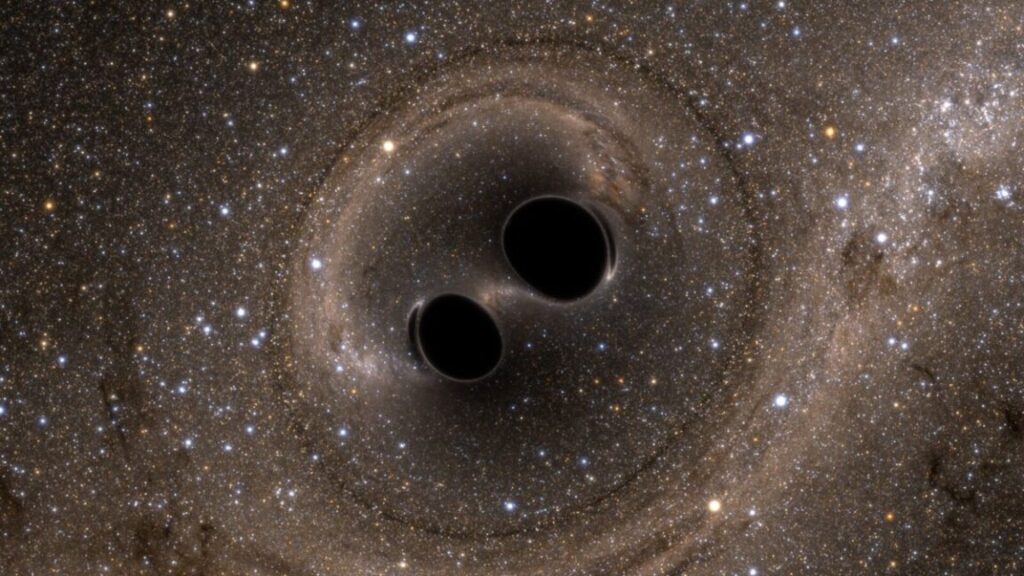

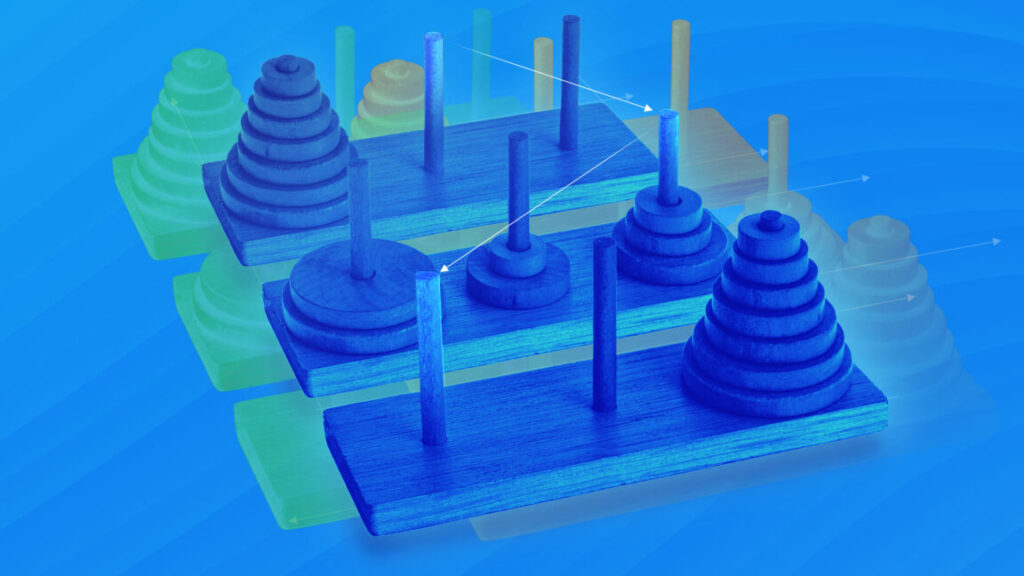

Four images from New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) were combined with color data from the spacecraft’s Ralph instrument to create this enhanced color global view of Pluto. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University/SWRI

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft got a fleeting glimpse of Pluto 10 years ago, revealing a distant world with a picturesque landscape that, paradoxically, appears to be refreshing itself in the cold depths of our Solar System.

The mission answered numerous questions about Pluto that have lingered since its discovery by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. As is often the case with planetary exploration, the results from New Horizons’ flyby of Pluto on July 14, 2015, posed countless more questions. First and foremost, how did such a dynamic world come to be so far from the Sun?

For at least the next few decades, the only resources available for scientists to try to answer these questions will be either the New Horizons mission’s archive of more than 50 gigabits of data recorded during the flyby, or observations from billions of miles away with powerful telescopes on the ground or space-based observatories like Hubble and James Webb.

That fact is becoming abundantly clear. Ten years after the New Horizons encounter, there are no missions on the books to go back to Pluto and no real prospects for one.

A mission spanning generations

In normal times, with a stable NASA budget, scientists might get a chance to start developing another Pluto mission in perhaps 10 or 20 years, after higher-priority missions like Mars Sample Return, a spacecraft to orbit Uranus, and a probe to orbit and land on Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus. In that scenario, perhaps a new mission could reach Pluto and enter orbit before the end of the 2050s.

But these aren’t normal times. The Trump administration has proposed cutting NASA’s science budget in half, jeopardizing not only future missions to explore the Solar System but also threatening to shut down numerous operating spacecraft, including New Horizons itself as it speeds through an uncharted section of the Kuiper Belt toward interstellar space.

The proposed cuts are sapping morale within NASA and the broader space science community. If implemented, the budget reductions would affect more than NASA’s actual missions. They would also slash NASA’s funding available for research, eliminating grants that could pay for scientists to analyze existing data stored in the New Horizons archive or telescopic observations to peer at Pluto from afar.

The White House maintains funding for newly launched missions like Europa Clipper and an exciting mission called Dragonfly to soar through the skies of Saturn’s moon Titan. Instead, the Trump administration’s proposed budget, which still must be approved by Congress, suggests a reluctance to fund new missions exploring anything beyond the Moon or Mars, where NASA would focus efforts on human exploration and bankroll an assortment of commercial projects.

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft undergoing launch preparations at Kennedy Space Center, Florida, in September 2005. Credit: NASA

In this environment, it’s difficult to imagine the development of a new Pluto mission to begin any time in the next 20 years. Even if Congress or a future presidential administration restores NASA’s planetary science budget, a Pluto mission wouldn’t be near the top of the agency’s to-do list.

The National Academies’ most recent decadal survey prioritized Mars Sample Return, a Uranus orbiter, and an Enceladus “Orbilander” mission in their recommendations to NASA’s planetary science program through 2032. None of these missions has a realistic chance to launch by 2032, and it seems more likely than not that none of them will be in any kind of advanced stage of development by then.

The panel of scientists participating in the latest decadal survey—released in 2022—determined that a second mission to Pluto did not merit a technical risk and cost evaluation report, meaning it wasn’t even shortlisted for consideration as a science priority for NASA.

There’s a broad consensus in the scientific community that a follow-up mission to Pluto should be an orbiter, and not a second flyby. New Horizons zipped by Pluto at a relative velocity of nearly 31,000 mph (14 kilometers per second), flying as close as 7,750 miles (12,500 kilometers).

At that range and velocity, the spacecraft’s best camera was close enough to resolve something the size of a football field for less than an hour. Pluto was there, then it was gone. New Horizons only glimpsed half of Pluto at decent resolution, but what it saw revealed a heart-shaped sheet of frozen nitrogen and methane with scattered mountains of water ice, all floating on what scientists believe is likely a buried ocean of liquid water.

Pluto must harbor a wellspring of internal heat to keep from freezing solid, something researchers didn’t anticipate before the arrival of New Horizons.

New Horizons revealed Pluto as a mysterious world with icy mountains and very smooth plains. Credit: NASA

So, what is Pluto’s ocean like? How thick are Pluto’s ice sheets? Are any of Pluto’s suspected cryovolcanoes still active today? And, what secrets are hidden on the other half of Pluto?

These questions, and more, could be answered by an orbiter. Some of the scientists who worked on New Horizons have developed an outline for a conceptual mission to orbit Pluto. This mission, named Persephone for the wife of Pluto in classical mythology, hasn’t been submitted to NASA as a real proposal, but it’s worth illustrating the difficulties in not just reaching Pluto, but maneuvering into orbit around a dwarf planet so far from the Earth.

Nuclear is the answer

The initial outline for Persephone released in 2020 called for a launch in 2031 on NASA’s Space Launch System Block 2 rocket with an added Centaur kick stage. Again, this isn’t a realistic timeline for such an ambitious mission, and the rocket selected for this concept doesn’t exist. But if you assume Persephone could launch on a souped-up super heavy-lift SLS rocket in 2031, it would take more than 27 years for the spacecraft to reach Pluto before sliding into orbit in 2058.

Another concept study led by Alan Stern, also the principal investigator on the New Horizons mission, shows how a future Pluto orbiter could reach its destination by the late 2050s, assuming a launch on an SLS rocket around 2030. Stern’s concept, called the Gold Standard, would reserve enough propellant to leave Pluto and go on to fly by another more distant object.

Persephone and Gold Standard both assume a Pluto-bound spacecraft can get a gravitational boost from Jupiter. But Jupiter moves out of alignment from 2032 until the early 2040s, adding a decade or more to the travel time for any mission leaving Earth in those years.

It took nine years for New Horizons to make the trip from Earth to Pluto, but the spacecraft was significantly smaller than an orbiter would need to be. That’s because an orbiter has to carry enough power and fuel to slow down on approach to Pluto, allowing the dwarf planet’s weak gravity to capture it into orbit. A spacecraft traveling too fast, without enough fuel, would zoom past Pluto just like New Horizons.

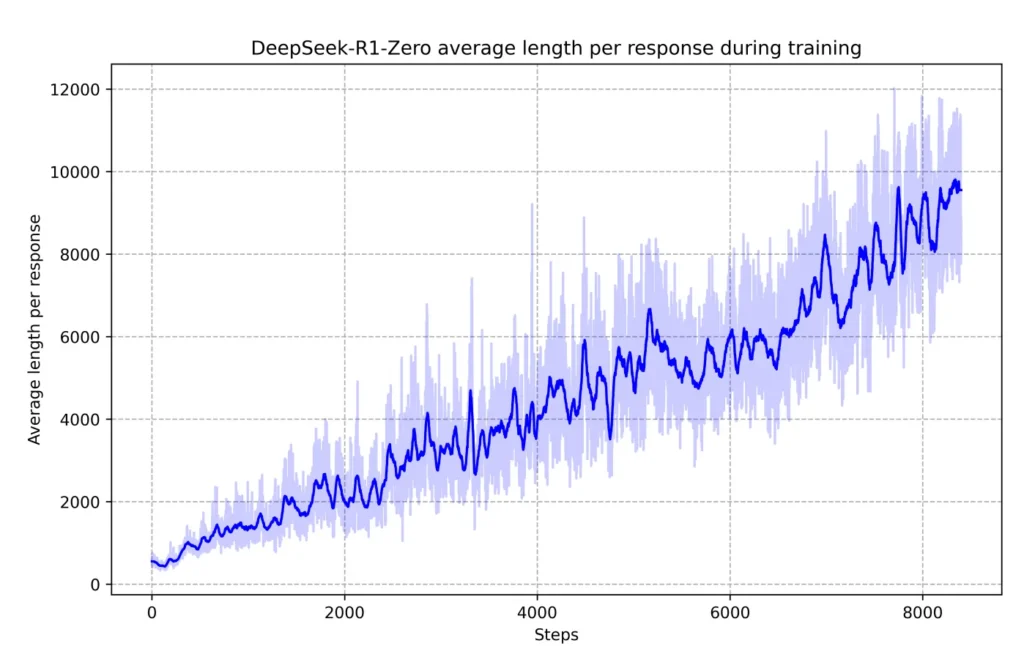

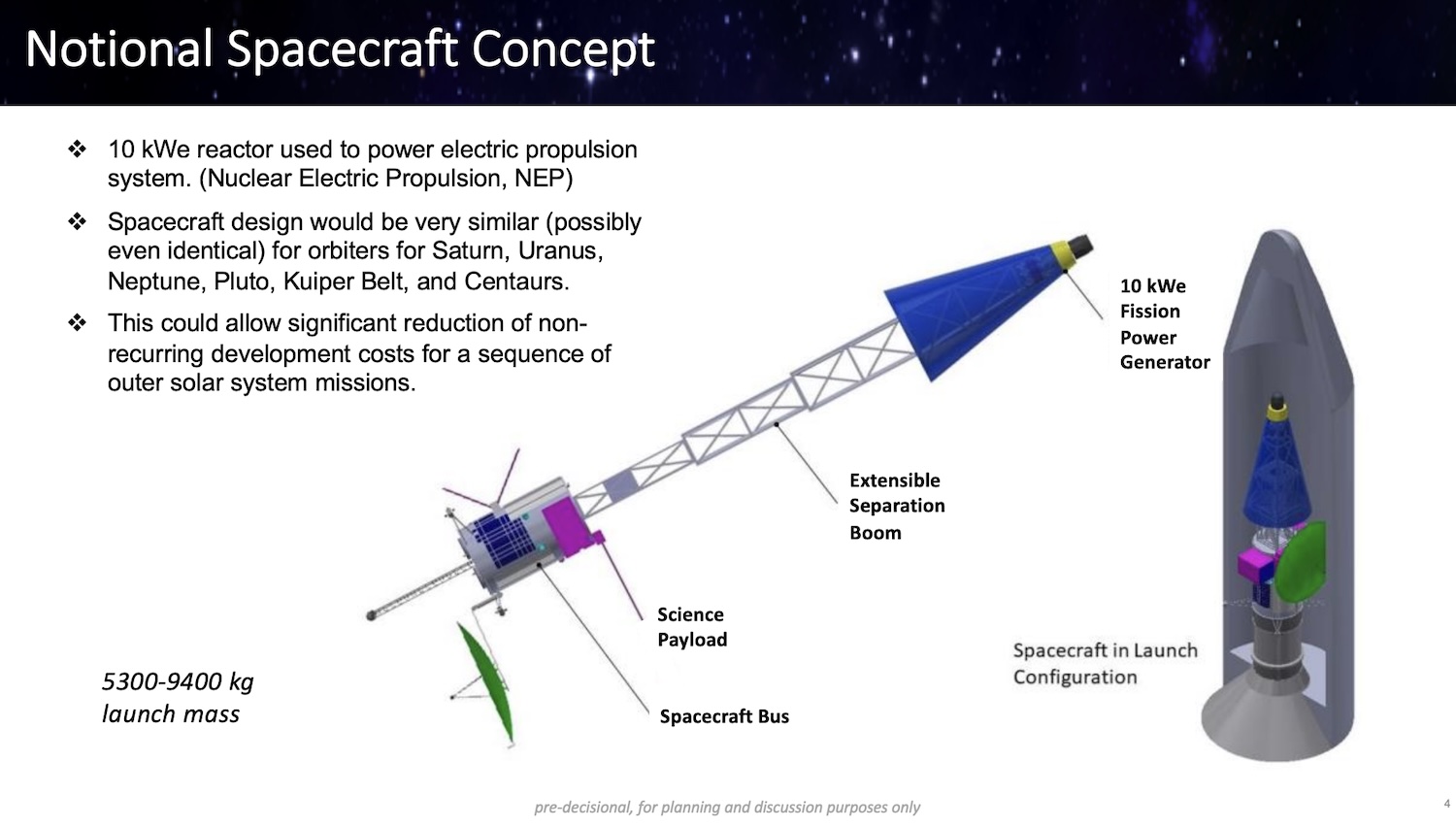

The Persephone concept would use five nuclear radioisotope power generators and conventional electric thrusters, putting it within reach of existing technology. A 2020 white paper authored by John Casani, a longtime project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who died last month, showed the long-term promise of next-generation nuclear electric propulsion.

A relatively modest 10-kilowatt nuclear reactor to power electric thrusters would reduce the flight time to Pluto by 25 to 30 percent, while also providing enough electricity to power a radio transmitter to send science data back to Earth at a rate four times faster, according to the mission study report on the Persephone concept.

However, nuclear electric propulsion technologies are still early in the development phase, and Trump’s budget proposal also eliminates any funding for nuclear rocket research.

A concept for a nuclear electric propulsion system to power a spacecraft toward the outer Solar System. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A rocket like SpaceX’s Starship might eventually be capable of accelerating a probe into the outer Solar System, but detailed studies of Starship’s potential for a Pluto mission haven’t been published yet. A Starship-launched Pluto probe would have its own unique challenges, and it’s unclear whether it would have any advantages over nuclear electric propulsion.

How much would all of this cost? It’s anyone’s guess at this point. Scientists estimated the Persephone concept would cost $3 billion, excluding launch costs, which might cost $1 billion or more if a Pluto mission requires a bespoke launch solution. Development of a nuclear electric propulsion system would almost certainly cost billions of dollars, too.

All of this suggests 50 years or more might elapse between the first and second explorations of Pluto. That is in line with the span of time between the first flybys of Uranus and Neptune by NASA’s Voyager spacecraft in 1986 and 1989, and the earliest possible timeline for a mission to revisit those two ice giants.

So, it’s no surprise scientists are girding for a long wait—and perhaps taking a renewed interest in their own life expectancies—until they get a second look at one of the most seductive worlds in our Solar System.

We saw the heart of Pluto 10 years ago—it’ll be a long wait to see the rest Read More »