Previously: #1

It feels so long ago that Covid and health were my beat, and what everyone often thought about all day, rather than AI. Yet the beat goes on. With Scott Alexander at long last giving us what I expect to be effectively the semi-final words on the Rootclaim debate, it seemed time to do this again.

I know no methodical way to find a good, let alone great, therapist.

Cate Hall: One reason it’s so hard to find a good therapist is that all the elite ones market themselves as coaches.

As a commentor points out, therapists who can’t make it also market as coaches or similar, so even if Cate’s claim is true then it is tough.

My actual impression is that the elite therapists largely do not market themselves at all. They instead work on referrals and reputation. So you have to know someone who knows. They used to market, then they filled up and did not have to, so they stopped. Even if they do some marketing, seeing the marketing copy won’t easily differentiate them from other therapists. There are many reasons why our usual internet approach of reviews is mostly useless here. Even with AI, I am guessing we currently lack enough data to give you good recommendations from feedback alone.

American life expectancy rising again, was 77.5 years (+1.1) in 2022.

Bryan Johnson, whose slogan is ‘Don’t Die,’ continues his quest for eternal youth, seen here trying to restore his joints. Mike Solana interviews Bryan Johnson about his efforts here more generally. The plan is to not die via two hours of being studied every day, what he finds is ideal diet, exercise and sleep, and other techniques and therapies including bursts of light and a few supplements.

I wish this man the best of luck. I hope he finds the answers and does not die, and that this helps the rest of us also not die.

Alas, I am not expecting much. His concept of ‘rate of aging’ does not strike me as how any of this is likely to work, nor does addressing joint health seem likely to much extend life or generalize. His techniques do not target any of the terminal aging issues. A lot of it seems clearly aimed at being healthy now, feeling and looking younger now. Which is great, but I do not expect it to buy much in the longer term.

Also one must note that the accusations in the responses to the above-linked thread about his personal actions are not great. But I would not let that sully his efforts to not die or help others not die.

I can’t help but notice the parallel to AI safety. I see Johnson as doing lots of mundane health work, to make himself healthier now. Which is great, although if that’s all it is then the full routine is obviously a bit much. Most people should do more of such things. The problem is that Johnson is expecting this to translate into defeating aging, which I very much do not expect.

Gene therapy cures first case of congenital deafness. Woo-hoo! Imagine what else we could do with gene therapies if we were ‘ethically’ allowed to do so. It is a sign of the times that I expected much reaction to this to be hostile both on the ‘how dare you mess with genetics’ front and also the ‘how dare you make someone not deaf’ front.

A ‘vaccine-like’ version of Wegovy is on the drawing board at Novo Nordisk (Stat+). If you are convinced you need this permanently it would be a lot cheaper and easier in this form, but this is the kind of thing you want to be able to reverse, especially as technology improves. Consider as parallel, an IUD is great technology but would be much worse if you could not later remove it.

The battle can be won, also Tracy Morgan really was playing Tracy Morgan when he played Tracy Morgan.

Page Six: Tracy Morgan says he ‘gained 40 pounds’ on weight-loss drugs: I can ‘out-eat Ozempic’

“It cuts my appetite in half,” the 55-year-old told Hoda Kotb and Jenna Bush Hager on the “Today” show in August 2023.

We used to eat a lot more, including more starch and sugar, without becoming obese, including people who did limited physical activity. According to these statistics, quite a lot more. Yes, we eat some new unhealthy things, but when people cut those things out without cutting calories, they do not typically lose dramatic amounts of weight.

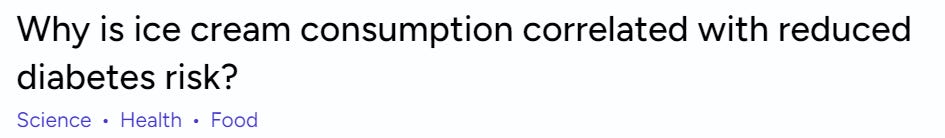

All right, why do the studies find ice cream is good for you, again? As a reminder the Atlantic dug into this a year ago, and now Manifold gives us some options, will resolve by subjective weighing of factors.

My money continues to be on substitution effects, with a side of several of the other things. Ice cream lets you buy joy, and buy having had dessert, at very little cost in calories, nutrition or health. No, it’s not great for you, but it’s not in the same category as other desserts like cake or cookies, and it substitutes for them while reducing caloric intake.

I am not about to short a 13% for five years, but I very much expect this result to continue to replicate. And I do think that this is one of the easier ways to improve your diet, to substitute ice cream for other desserts.

The NIH is spending $189 million dollars to do a detailed 10,000 person study to figure out what you should eat.

Andrea Peterson (WSJ): Scientists agree broadly on what constitutes a healthy diet—heavy on veggies, fruit, whole grains and lean protein—but more research is showing that different people respond differently to the same foods, such as bread or bananas.

I would instead claim we have broad agreement as to what things we socially label as ‘healthy’ versus ‘unhealthy,’ with little if any actual understanding of what is actually healthy or unhealthy, and the broad expectation among the wise that the answers vary greatly between individuals.

Elizabeth and his fellow participants spend two weeks each on three different diets. One is high fat and low carb; another is low on added sugars and heavy on vegetables, along with fruit, fish, poultry, eggs and dairy; a third is high in ultra-processed foods and added sugars.

This at best lets us compare those three options to each other under highly unnatural conditions, where the scientists apply great pressure to ensure everyone eats exactly the right things, and that have to severely alter people’s physical activity levels. A lot of why some diets succeed and others fail is how people actually act in practice, including impact on exercise. Knowing what set of foods in exactly what quantities and consumption patterns would be good if someone theoretically ate exactly that way is nice, but of not so much practical value.

Also, they are going to put each person on each diet for only two weeks? What is even the point? Yes, they draw blood a lot, measure heart rates, take other measures. Those are highly noisy metrics at best, that tell us little about long term impacts.

This does not seem like $189 million well spent. I cannot imagine a result that would cause me to change my consumption or much update my beliefs, in any direction.

This both is and is not how all of this works:

Keto Carnivore: [losing weight] not hard compared to being fat, in pain, chronically fatigued, or anxious/depressed/psychotic. Those things are extremely motivating. It’s only hard if it doesn’t work, or the body is fighting it (like caloric restriction without satiation, or constant cravings).

exfatloss: Can💯confirm. Do you know how much willpower I need to do a pretty strict ketogenic diet?

0. Because the alternative is not having a career/life and feeling like shit all the time from sleep deprivation.

When it obviously works, motivation is not an issue.

To clarify, I have a very rare and specific circadian rhythm disorder that therapeutic keto fixes. 99.99% of people don’t have this issue and therefore won’t get the same benefits I do.

Motivation is not an issue for me, in the sense that I have no doubt that I will continue to do what it takes to keep the weight off.

That does not mean it is easy. It is not easy. It is hard. Not every day. Not every hour. But often, yes, it is hard, the road is long. But yeah, the alternative is so obviously worse that I know I will do whatever it takes, if it looks like I might slip.

‘‘What we wish we knew entering the aging field.’ I hear optimistic things that we will start to see the first real progress soon, but it is not clear people wouldn’t say those things anyway. It certainly seems plausible we could start making rapid progress soon. Aging is a disease. Cure it.

Ken Griffin donates $400 million to cancer hospital Sloan Kettering. Not the most effective altruism available, but still, what a mensch.

Sulfur dioxide in particular is a huge deal. The estimate here is that a 1 ppb drop in levels, a 10% decline in pollution, would increase life expectancy by a whopping 1.2 years. Huge if even partially true, I have not looked into the science.

Someone should buy 23AndMe purely to safeguard its data. Cost is already down to roughly $20 per person’s data.

Yes, Schizophrenia is mostly genetic.

HIPPA in practice is a really dumb law, a relic of a time when digital communications did not exist. The benefits of being able to email and text doctors vastly exceed the costs, and obviously so. Other places like the UK don’t have it and it’s much better.

The story of PEPFAR, and how it turned out to be dramatically effective to do HIV treatment instead of HIV prevention, against the advice of economists. Back then there were no EAs, but the economists were making remarkably EA-like arguments, while making classic errors like citing studies showing very low cost estimates per life saved for prevention that failed to replicate, including ignoring existing failed replications. And they failed to understand that the moral case for treatment allowed expansion of the budget and also that treatment halted transmission, and thus was also prevention.

In many senses, it is clear that Bush ‘got lucky’ here, with the transmission effect and adherence rates exceeding any reasonable expectations, while prevention via traditional methods seems to have proven even less effective than we might have expected. If I had to take away three key lessons, they would be that you need to do larger scale empiricism to see what works and not count on small studies, and that you should care a lot about making the moral or obvious case for what you are doing, because budgets for good causes are never fixed. People adjust them based on how excited they are to participate. And I do not think this is stupid behavior on anyone’s part, focusing on things where you score clear visible wins guards against a lot of failure modes, even at potential large efficiency costs, while usually still being more than efficient enough to be worth doing on its own merits.

Say it with me, the phrase is catching on, except looks like this was eventually approved anyway?

Henry: TIL there was a company that sold a baby sock with an spo2 monitor that sent a push notification if your baby stopped breathing until the FDA forced them to stop selling them because only doctors should be able to see a blood oxygen number.

> The FDA objection was based on the fact that the wearable had the capacity to relay a live display of a baby’s heart rate and oxygen levels, which is critical data that a doctor should interpret, especially in vulnerable populations.

FDA delenda est.

If I try, yes, I can tell a story where people think ‘oh I do not have to check on my baby anymore because if something goes wrong the sock will tell me’ and this ends up being a bad thing. You can also tell that story about almost anything else.

Some very silly people argue that it is not preventing schizophrenia unless you do so in a particular individual, if you do it via polygenic selection then it is ‘replacement.’ Scott Alexander does his standard way overthinking it via excruciating detail method of showing why this is rather dumb.

90% of junior doctors in South Korea strike to protest against doctors. Specially, against admitting 2,000 more students each year to medical schools. One can say ‘in-group loyalty’ or ‘enlightened self-interest’ if one wants. Or realize this is straight up mafia or cartel behavior, and make it 5,000.

Brian Patrick Moore: Good thing we don’t have some crazy thing like this in the US

Of all the low hanging fruits in health care, ‘lots of capable people want to be doctors and we should train more of them to be doctors’ has to be the lowest hanging of all.

Vaccine mandates for health care workers worsened worker shortages on net, the ‘I don’t want to get vaccinated or told what to do’ effect was bigger than the ‘I am safer now’ effect, claiming a 6% decline in healthcare employment. Marginal Revolution summarized this as the mandate backfiring. We do see that a cost was paid here. It is not obvious the cost is not worthwhile, and also if someone in healthcare would quit rather than be vaccinated one questions whether you wanted them working that job.

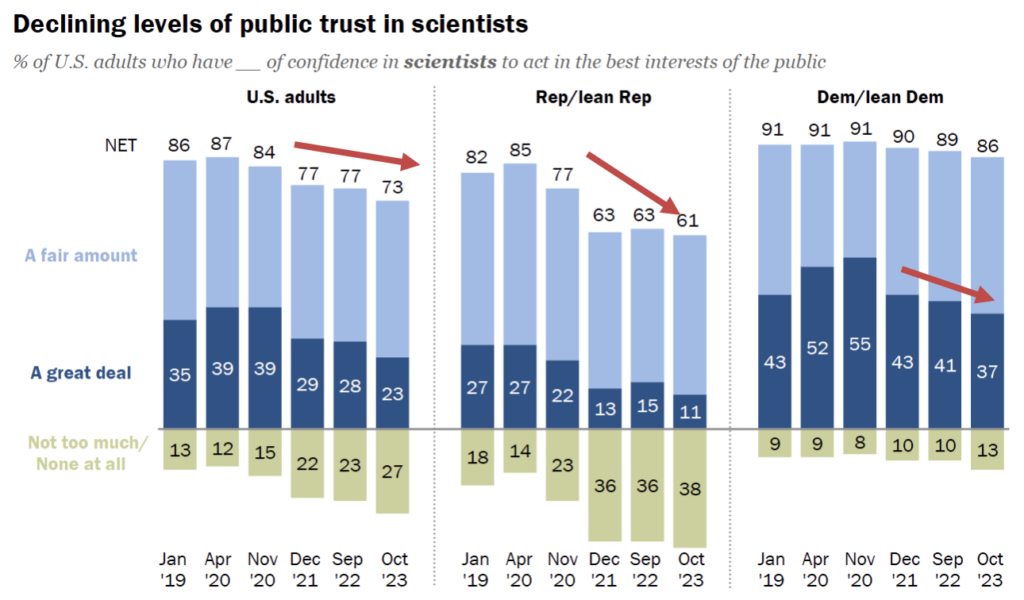

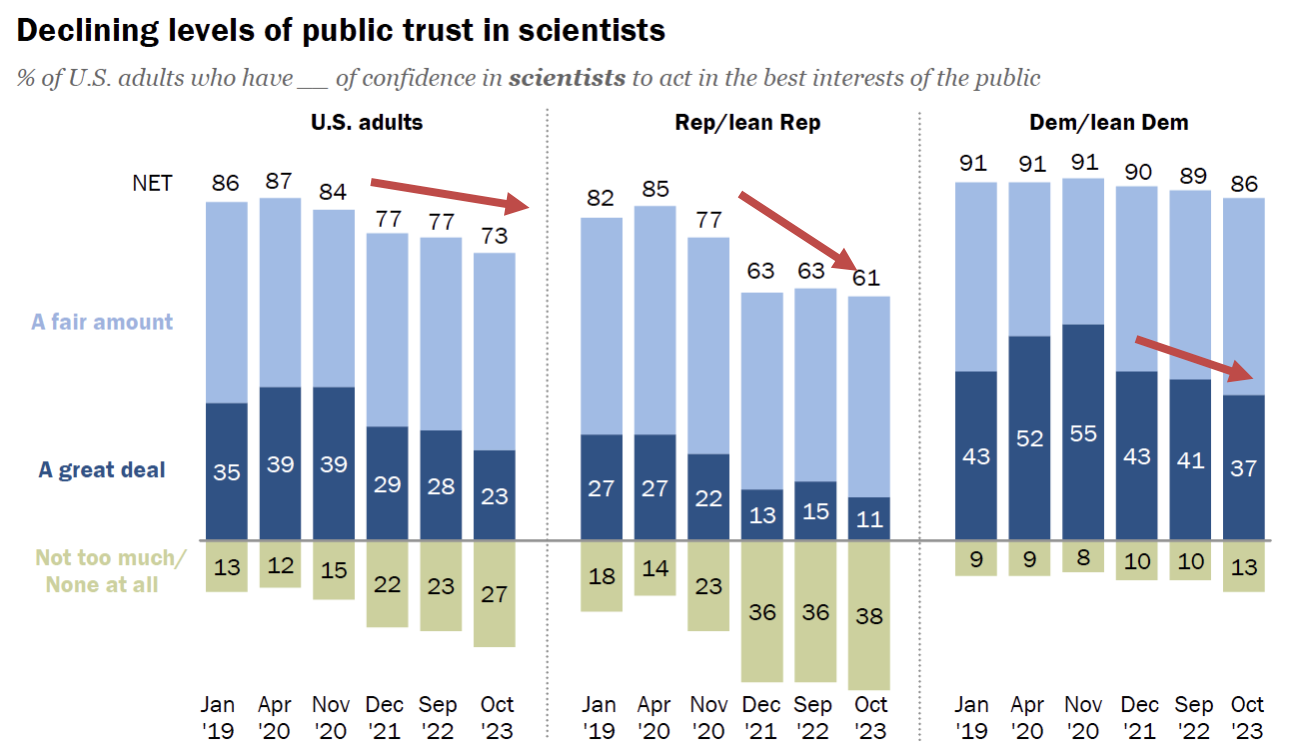

Katelyn Jetelina asks Kelley Krohnert why science lost public trust during the pandemic. The default is still ‘a fair amount’ of trust but the decline is clear especially among Republicans.

Here are the core answers given:

Everything sounds like a sales pitch

From Paxlovid to vaccines to masks to ventilation. Public health sounded (and still sounds like) a used car salesman for many different reasons:

-

Data seems crafted to feed the pitch rather than the pitch crafted by data. Overly optimistic claims weren’t well-supported by data, risks of Covid were communicated uniformly which meant the risks to young people were exaggerated, and potential vaccine harms were dismissed. Later, when it was time to pitch boosters, public health pivoted on a dime to tell us vaccine protection wanes quickly. How did we get here?

-

Data mistakes …

-

Messaging inaccuracies. …

-

Mixing advocacy with scientific communication … The latest example was a long Covid discussion at a recent congressional hearing, and one of the top long Covid doctors saying, “The burden of disease from long Covid is on par with the burden of cancer and heart disease.”

I would give people more credit. Focusing on what things ‘sound like’ was a lot of what got us into this mess.

The issue wasn’t that everything ‘sounded’ like a sales pitch.

The problem was that everything was a sales pitch.

People are not scientific experts, but they can recognize a sales pitch.

The polite way to describe what happened was ‘scientists and doctors from Fauci on down decided to primarily operate as Simulacra Level 2 operators who said what they thought would cause the behaviors they wanted. They did not care whether their statements matched the truth of the physical world, except insofar as this would cause people to react badly.

As for this last item, I mean, there is a lot of selection bias in who becomes a ‘top long Covid doctor’ so it is no surprise that he was up there testifying (in a mask in 2024) that long Covid is on par with the burden of cancer and heart disease, a comment that makes absolutely zero sense.

Indeed, statements like that are not ‘mixing advocacy with scientific communication.’ My term for them is Obvious Nonsense, and the impolite word would be ‘lying.’

Information that would have been helpful was never provided

Indeed, ‘ethicists’ and other experts worked hard to ensure that we never found out much key information, and that we failed to communicate other highly useful informat we did know or damn well have enough to take a guess about, in ways that ordinary people found infuriating and could not help but notice was intentional.

This has been going on forever in medicine, better to tell you nothing than information ‘experts’ worry you won’t interpret or react to ‘properly,’ and better not to gather information if there is a local ethical concern no matter the cost of ignorance, such as months (or in other cases years) without a vaccine.

A disconnect between what I experienced on the ground and the narrative I was hearing

As in, Covid-19 in most cases wasn’t that scary in practice, and people noticed. I do think this one was difficult to handle. You have something that is 95%-99% to be essentially fine (depending on your threshold for fine) but will sometimes kill you. People’s heuristics are not equipped to handle it.

She concludes that some things are improving. But it is too little, too late. Damage is mostly done, and no one is paying attention anymore, and also they are still pushing more boosters. But this is at least the start of a real reckoning.

As an example of this all continuing: I have been told that The New York Times fact checks its editorials, and when I wrote an editorial I felt fact checked, but clearly it does not insist on those checks in any meaningful sense, since they published an op-ed claiming the Covid vaccine saved 3 million lives in America in its first two years. That makes zero sense. America has only 331.9 million people, and the IFR for Covid-19 on first infection is well under 1% even for the unvaccinated. The vaccines were amazing and saved a lot of lives. Making grandiose false claims does not help convince people of that.

Matt Yglesias has thoughts about Covid four years after.

He is still presenting More Lockdowns as something that would have been wise?

If the Australian right could implement hard lockdowns to control the virus, I believe the American right could have as well. This probably would have saved a ton of lives. Australia and other countries with tougher lockdown policies saw dramatically lower mortality.

Or maybe not?

Even a really successful lockdown regime couldn’t be sustained forever, and there was a price to pay in Australia and Finland and everywhere else once you opened up.

I mean, yes those other countries had lower mortality, but did America have the prerequisites to make such policies sustainable, where they work well enough you can loosen them and they still work and so on? I think very clearly no. Trying to lock down harder here would have been a deeply bad idea, because for better and also for worse we lacked the state and civilizational capacity to pull it off.

Then we have these two points, which seem directly contradictory? I think the second one is right and the first is wrong. The hypocrisy was a really huge deal.

I think the specific hypocrisy of some progressive public health figures endorsing the Floyd protests is somewhat overblown.

…

After Floyd, it became completely inconceivable that any liberal jurisdiction in America would actually enforce any kind of tough Covid rules.

He makes this good note.

Speaking of drift, I think an under-discussed aspect of the Biden administration is they initiated a bunch of rules right when they took office and vaccine distribution was just starting and had no plan to phase them out, seemingly ever. When they got sued over the airplane mask mandate, they fought in court to maintain it.

At minimum this was a missed opportunity to show reasonableness and competence. At worst, this was a true-colors moment for many people, who remember even if they don’t realize they remember.

Matt also points out that there has been no reckoning for our failures. America utterly failed to make tests available in reasonable fashion. Everyone agrees on this, and no one is trying to address the reasons that happened. The whole series of disingenuous mask policies and communications also has had no reckoning. And while Democrats had an advantage on Covid in 2020, their later policies did not make sense, pissed people off and destroyed that advantage.

Scott Alexander posted an extensive transcript and thoughts on the Rootclaim debate over Covid origins. The natural origin side won decisively, and Scott was convinced. That does not mean there are not ongoing attempts to challenge the result, such as these. An hours-long detailed debate is so much better than not having one, but the result is still highly correlated with the skills and knowledge and strategies of the two debaters, so in a sense it is only one data point unless you actually go over the arguments and facts and check everything. Which I am not going to be doing.

(I mean, I could of course be hired to do so, but I advise you strongly not to do that.)

To illustrate how bad an idea that would be, Scott Alexander offers us the highlights from the comments and deals with various additional arguments. It ends with, essentially, Rootclaim saying that Scott Alexander did not invest enough time in the process and does not know how to do probability theory, and oh this would all be sorted out otherwise. Whether or not they are right, that is about as big a ‘there be dragons and also tsuris’ sign as I’ve ever seen.

The one note I will make, but hold weakly, is that it seems like people could do a much better job of accounting for correlated errors, model uncertainty or meta uncertainty in their probability calculations.

As in, rather than pick one odds ratio for the location of the outbreak being at the wet market, one should have a distribution over possible correct odds ratios, and then see how much those correlate with correct odds ratios in other places. Not only am I not sure what to make of this one rather central piece of offered evidence, who is right about the right way to treat that claim would move me a lot on who is right about the right way to treat a lot of other claims, as well. The practical takeaway is that, without any desire to wade into the question of who is right about any particular details or overall, it seems like everyone (even when not trolling) is acting too confident based on what they think about the component arguments, including Scott’s 90% zoonosis.

My actual core thinking is still that either zoonosis or a lab leak could counterfactually have quite easily caused a pandemic that looks like Covid-19, our current ongoing practices at labs like Wuhan put as at substantial risk for lab leaks that cause pandemics that could easily be far worse than Covid-19.

I do not see any good arguments that a lab leak or zoonosis couldn’t both cause similar pandemics, everyone is merely arguing over which caused the Covid-19 pandemic in particular. And I claim that this fact is much more important than whether Covid-19 in particular was a lab leak.

‘I’m 28. And I’m scheduled to die in May.’

Rupa Subramanya (The Free Press): Zoraya ter Beek, 28, expects to be euthanized in early May.

Her plan, she said, is to be cremated.

“I did not want to burden my partner with having to keep the grave tidy,” ter Beek texted me. “We have not picked an urn yet, but that will be my new house!”

She added an urn emoji after “house!”

Ter Beek, who lives in a little Dutch town near the German border, once had ambitions to become a psychiatrist, but she was never able to muster the will to finish school or start a career. She said she was hobbled by her depression and autism and borderline personality disorder. Now she was tired of living—despite, she said, being in love with her boyfriend, a 40-year-old IT programmer, and living in a nice house with their two cats.

She recalled her psychiatrist telling her that they had tried everything, that “there’s nothing more we can do for you. It’s never gonna get any better.”

At that point, she said, she decided to die. “I was always very clear that if it doesn’t get better, I can’t do this anymore.”

…

“I’m seeing euthanasia as some sort of acceptable option brought to the table by physicians, by psychiatrists, when previously it was the ultimate last resort,” Stef Groenewoud, a healthcare ethicist at Theological University Kampen, in the Netherlands, told me. “I see the phenomenon especially in people with psychiatric diseases, and especially young people with psychiatric disorders, where the healthcare professional seems to give up on them more easily than before.”

Theo Boer, a healthcare ethics professor at Protestant Theological University in Groningen, served for a decade on a euthanasia review board in the Netherlands. “I entered the review committee in 2005, and I was there until 2014,” Boer told me. “In those years, I saw the Dutch euthanasia practice evolve from death being a last resort to death being a default option.” He ultimately resigned.

Once again, we seem unable to be able to reach a compromise between ‘this is not allowed’ and ‘this is fully fine and often actively encouraged.’

This is especially true when anything in-between would be locally short-term worse for those directly involved, no matter what the longer-term or broader implications.

We have now run the experiment on euthanasia far enough to observe (still preliminary, but also reasonably conclusive) results on what happens when you fully accept option two. I am ready to go ahead and say that, if we have to choose one extreme or the other, I choose ‘this is not allowed.’

Ideally I would not go with the extreme. I would instead choose a relatively light ‘this is not allowed’ where in practice we mostly look the other way. But assisting you would still be taking on real legal risk if others decided you did something wrong, and that risk would increase if you were sufficiently brazen that your actions weakened the norms against suicide or you were seen as in any way applying pressure.

However, I worry that if the norms are insufficiently strong, they fail to be an equilibrium, and we end up with de facto suicide booths and medical professionals suggesting euthanasia to free up their budgets and relatives trying to get you out of the way or who want their inheritance early, a lot of ‘oh then kill yourself’ as if that is a reasonable thing to do, and life being cheap.

New world’s most expensive drug costs $4.25 million dollars. It is a one-off treatment for metachromatic leukodystrophy.

Saloni: Fascinating read about the world’s newest most expensive drug ($4M)

A one-off treatment for metachromatic leukodystrophy, a rare genetic condition where kids develop motor & neurological disease, and most die in childhood.

42% of untreated died before 6 yo versus 0% of treated.

Kelsey Piper: $4M is of course an eye-popping amount of money, but this is apparently 1/40,000 US births. Would you pay $100 to guarantee that, if your baby is one of them, they will likely be healthy and live a normal life instead of dying a slow horrible death over several years? I would!

So it’s worth it at $4M, and also the price will come down, and also lots of other people will benefit from the medical developments that come with it. What a win.

Dave Karsten: This just feels straightforward reasonable give usual costing for regulatory interventions if it’s a “saves 0.58 human lifetimes per dose” price (Yes obvi other hazards await any patient in the future and maybe you should NPV the value also, but you get my point).

The disease is progressive. The 58% of children who live to age 6 are not going to get anything like full quality of life, with declining function over time.

So yes, assuming this is a full cure then this does seem worth it for America, on the principle that a life saved is worth about $10 million. In theory we should be willing to pay at least $5 million for this drug, possibly up to $10 million, before it would cost more than it is worth.

Thus, one could say this is priced roughly correctly. Why shouldn’t a monopolist be charing roughly half of consumer surplus, especially if we want to incentivize creating more such products? Seems like about the right reward.

(Obviously, one could say EA-style things about how that money might be better spent. I am confident telling those people they are thinking on the wrong margin.)